The courthouse in Kenora, Ont., is the base for a large judicial district in Northwestern Ontario. Six Crown attorneys came and went there between May and October of last year, writing back to their managers in Ottawa to complain about the high workload.Alyssa Lloyd/The Globe and Mail

Federal prosecutors warned their bosses that severe understaffing and disorganization in a Northwestern Ontario district were damaging the justice system in the vast area and resulting in a “brutal quality” of service to Indigenous communities.

In a series of memos and e-mails to a Public Prosecution Service of Canada supervisor between May and October of last year, six Crown attorneys who were rotated into the Kenora judicial district reported a litany of concerns. The inconsistent and inadequate staffing they bluntly described is playing out against the backdrop of an escalating drug crisis and a revolving door of justices of the peace after two JPs in Kenora retired, one of them amid allegations of racism.

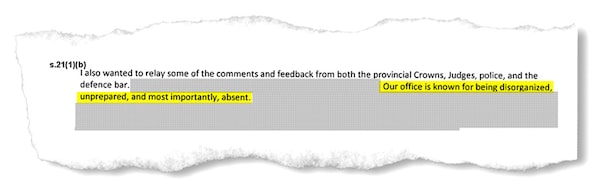

“Our office is known for being disorganized, unprepared and most importantly, absent,” Crown attorney Jessica Corbeil said in a May 25, 2018, e-mail to Johanne Léger, a senior counsel and agent supervisor in the PPSC’s National Capital Region Office in Ottawa. The e-mail was among the correspondence obtained by The Globe and Mail under access-to-information laws.

An excerpt from the 2018 e-mail between Crown attorney Jessica Corbeil to agent supervisor Johanne Léger in Ottawa. Ms. Corbeil was based in the Kenora district, which services an array of small fly-in communities (see map below).

0

150

KM

Hudson

Bay

Ont.

Detail

Fort Severn

MANITOBA

Bearskin Lake

Sachigo Lake

Kingfisher Lake

Muskrat Dam

Sandy Lake

Keewaywin

Deer Lake

Wunnumin

Lake

North Spirit Lake

Poplar Hill

Cat Lake

Pikangikum

ONTARIO

Kenora

17

Thunder Bay

Lake

Superior

MINNESOTA

john sopinski/the globe and mail, source:

TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

0

150

KM

Hudson Bay

Ont.

Detail

Fort Severn

MANITOBA

Bearskin Lake

Sachigo Lake

Kingfisher Lake

Muskrat Dam

Sandy Lake

Wunnumin Lake

Keewaywin

Deer Lake

North Spirit Lake

Poplar Hill

Cat Lake

Pikangikum

ONTARIO

Kenora

17

Thunder Bay

MINNESOTA

Lake Superior

john sopinski/the globe and mail, source: TILEZEN;

OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

MANITOBA

Fort Severn

Ont.

Hudson Bay

Detail

Bearskin Lake

Sachigo Lake

Kingfisher Lake

Muskrat Dam

Sandy Lake

Wunnumin Lake

Keewaywin

Deer Lake

North Spirit Lake

Poplar Hill

Cat Lake

Pikangikum

ONTARIO

Kenora

17

Thunder Bay

Wawa

Lake Superior

0

150

MINNESOTA

KM

john sopinski/the globe and mail, source: TILEZEN;

OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

The Kenora judicial district, which includes 13 fly-in communities, is geographically sprawling and logistically challenging. Some remote First Nations hold fly-in court in their communities as infrequently as three times a year, so when a federal Crown is unavailable and other arrangements cannot be made, a case might be delayed for months. Delays can have serious implications for those facing charges: Although presumed innocent until proven guilty, they might be held at the Kenora jail until their case concludes, or, if they are released on bail, they may be required to remain in the city, far from their communities and support systems.

For years, the district was served by private-sector lawyers contracted to conduct prosecutions on behalf of the PPSC, an independent organization that exists outside the Justice Department. Only briefly – from 2017 to 2018 – was there a full-time federal Crown attorney. After that person left, the PPSC could not find local lawyers to adequately staff the role, so Crowns started being rotated one at a time into a makeshift office in a Canada Post building, typically for two weeks at a time. Two local lawyers are also available on a part-time basis.

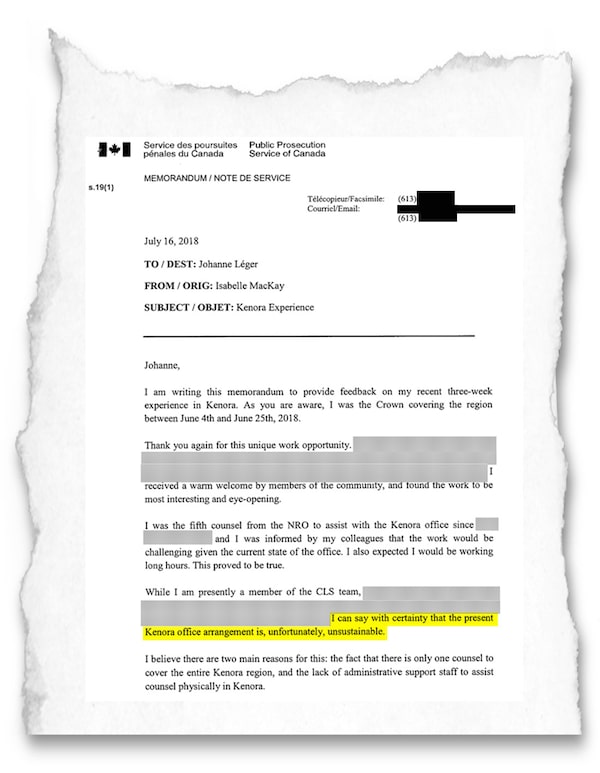

The Crown attorneys who were sent to Kenora last year enumerated the consequences of the staffing arrangement, including: an “unsustainable” workload; files in “complete disarray;” cramped office space and outdated resources; scheduling conflicts and missed appearances; the outsourcing of work to provincial prosecutors and private-sector lawyers; and lost credibility with defence lawyers, judges and Indigenous leaders.

More correspondence to Ms. Léger, this time from prosecutor Isabelle MacKay, describes the 'unsustainable' workload in the Kenora district, where she served for three weeks.

While provincial prosecutors handle Criminal Code charges, federal Crowns in Ontario are responsible for prosecuting offences under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

“It was simply impossible to complete all the required tasks to provide high-quality service to local stakeholders – especially to local Aboriginal communities victimized by drug trafficking,” federal prosecutor Timothy Radcliffe wrote in an Oct. 17 e-mail to Ms. Léger. In an earlier e-mail to his Crown colleagues, Mr. Radcliffe was more frank, referring to the “brutal quality of our service to the Indigenous communities surrounding Kenora.”

In response to the prosecutors’ concerns, the PPSC told The Globe it is planning to open a permanent office in Kenora. It will be staffed by two federal prosecutors and a legal assistant – the resourcing level that was advocated internally by several Crowns more than a year ago.

“We really can’t do this anymore, with the volume of work, with one person,” the region’s chief federal prosecutor, Tom Raganold, said in a recent interview, noting that the rotation was always meant to be a short-term solution. “We’re doing everything we can to increase the service to the area and improve it.”

One of the full-time prosecutors is expected to start in Kenora in October, but it could be months before the other two positions are filled, Mr. Raganold said. Until the federal Public Services and Procurement department secures a larger space for the permanent office, there is not enough room in the current location for more than one person to work. In the meantime, prosecutors and support staff at the regional office in Ottawa will continue to provide assistance to the Crowns in Kenora.

Criminal-defence attorneys say the Crown rotation is causing delays and complicating plea and sentencing negotiations, and First Nations leaders say the status quo is untenable in a region with an intensifying drug problem and an overwhelmingly Indigenous jail population.

This past spring, the Grand Council Treaty #3, which represents First Nations communities in Northwestern Ontario, wrote a letter to the PPSC urging the service to immediately create full-time Crown positions in the district. “The safety of Treaty #3 citizens and the epidemic of drugs in our territory is of the utmost priority in our Nation,” Grand Chief Francis Kavanaugh wrote in the May 28 letter, which was obtained by The Globe.

Arthur Huminuk, the Grand Council’s justice director, said the rotating Crowns do not have the time to foster relationships or develop a cultural understanding of the First Nations communities they serve. “There’s no way they can do their work effectively,” he said. “They’re just zooming around.”

A federal prosecutor might be scheduled to be in court in Kenora and a fly-in community at the same time. In those instances, the federal Crown can ask a provincial prosecutor or a contracted private-sector lawyer to act on the PPSC’s behalf – a practice that occurs outside the district as well.

Kenora-based criminal-defence lawyer John Bilton said the situation is complicated by the fact that some of the files in the judicial district are managed remotely from Ottawa. “It’s almost Wizard of Oz,” he said. “It’s hard to figure out who’s behind the curtain.”

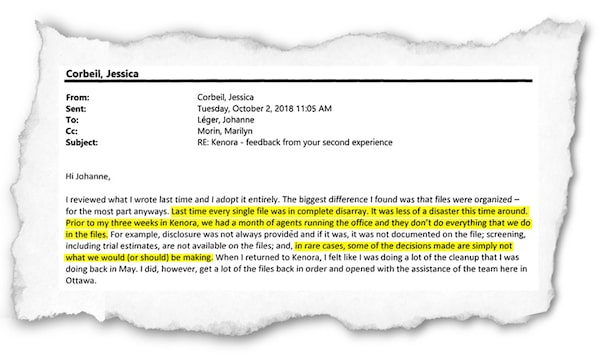

Beyond the inconsistencies and confusion, Ms. Corbeil, who was one of the Crown attorneys who raised concerns, pointed to another consequence of the PPSC’s reliance on others to prosecute its cases: “In rare cases, some of the decisions made are simply not what we would (or should) be making,” she wrote in an e-mail dated Oct. 2, following a second stint in the district.

An excerpt from Ms. Corbeil's e-mail on Oct. 2, 2018, to Ms. Léger in Ottawa.

In the Kenora courthouse one recent day, it became apparent that justices of the peace, who preside over most bail hearings in the province, are also being rotated into the district for short periods. A spokeswoman for the Ontario Court of Justice said in an e-mail that an advisory committee is conducting interviews after Kenora’s two full-time JPs retired, one in May and another, Robert McNally, this past December. By stepping down, Mr. McNally avoided a scheduled hearing into allegations of judicial misconduct. According to a 2017 court transcript, he told Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services lawyer Shannon McDunnough that her “ancestors probably scalped” British comedian Benny Hill.

Mr. Bilton said the state of affairs in the Kenora district is just one example of the disparity of services to Indigenous peoples. “You can see this in every aspect of life in the North,” he said. “Pikangikum [First Nation] didn’t get power lines until December of 2018. … We’re living in a country that says, ‘First Nations peoples: You’re second-class.’”

He described a multitude of challenges in the district: Fly-in court is unpredictable because of the weather; First Nations are grappling with addiction and poverty in the aftermath of historical injustices, including the Indian Residential School system in which Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their communities; and no additional judges are on hand to help if the schedule is overloaded at fly-in court, which might be held in a restaurant or school gymnasium.

Criminal-defence lawyer Laurelly Dale, who has offices in Kenora and Toronto, said the rotation is hindering her plea and sentencing negotiations, especially if a new prosecutor takes over before the matter is resolved. “I’m not trying to infer any sort of maliciousness on the part of the Crowns,” she said. “I actually have a lot of empathy for them because they’re being parachuted into these situations."