A man cools off at a Vancouver misting station in June of 2021, when an atmospheric 'heat dome' enveloped much of the Pacific Northwest, bringing extreme temperatures to communities without widespread air conditioning.Jennifer Gauthier/Reuters

More • Map: Projected extreme heat and rain across Canada • Code Minimum: A Globe series • Reader callout: Share your extreme-weather stories

Roberta Lalonde lived by herself in a condo building for people over 55 when the deadliest weather event in Canadian history began in British Columbia on June 25, 2021.

For a week, high atmospheric pressure trapped the hot air underneath, creating a phenomenon known as a heat dome. Outdoors, with the humidity, it felt like 44 degrees Celsius. Indoors, it could be just as bad, and Ms. Lalonde struggled. Like most other B.C. dwellings, her unit in Chilliwack didn’t have air conditioning.

After her family didn’t hear from her for several days, a relative found the 74-year-old lifeless in her bed, while a couple of pedestal fans still ran in the condo. Her death certificate says she died on June 27.

Roberta Lalonde was one of hundreds of British Columbians who died in 2021's extreme heat.Courtesy of Christine Lalonde

An investigation by a B.C. coroner’s panel found there were 619 heat-related deaths during the week-long event. Nearly 98 per cent of the victims died indoors, mostly in homes without adequate cooling systems. The panel’s report recommended remedies often cited when dealing with heat waves: setting up a co-ordinated public heat alert and response system, reaching out to vulnerable people, increasing the tree canopy.

But given that a changing climate will cause increasingly hotter weather, the panel also brought up a new recommendation: that the 2024 edition of the B.C. building code require new homes to have features that lessen the impact of extreme heat. This could be accomplished either through passive cooling, such as using sun-reflecting materials, or active cooling systems. “Current building codes in British Columbia do not consider cooling in the same manner as heating requirements. As building codes are revised they will need to reflect the latest climate science and consider cooling needs,” the panel’s report said.

That same observation could apply as well to construction rules in other parts of the country. A months-long Globe and Mail examination of building codes and bylaws across Canada shows that they lack provisions to help new buildings cope with the increasing rate and severity of hailstorms, floods, wildfires, tornadoes – and extreme heat.

Projected number of days over 30°C

by scenario

Top metropolitan areas

Recent history (1976-2005)

Low carbon scenario (2051-2080)

High carbon scenario (2051-2080)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

78.8

Windsor

63.3

Hamilton

Niagara Falls–

St. Catharines

63

63

Brantford

62

Kelowna

61

London

57

Ottawa

55

Toronto

54.5

Belleville

54

Lethbridge

54

Regina

54

Montreal

53.7

Kitchener–

Cambridge–

Waterloo

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO

Projected number of days over 30°C by scenario

Top metropolitan areas

Recent history (1976-2005)

Low carbon scenario (2051-2080)

High carbon scenario (2051-2080)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

78.8

Windsor

63.3

Hamilton

Niagara Falls–

St. Catharines

63

63

Brantford

62

Kelowna

61

London

57

Ottawa

55

Toronto

54.5

Belleville

54

Lethbridge

54

Regina

54

Montreal

53.7

Kitchener–

Cambridge–

Waterloo

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO

Projected number of days over 30°C by scenario

Top metropolitan areas

Recent history

(1976-2005)

Low carbon scenario

(2051-2080)

High carbon scenario

(2051-2080)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

78.8

Windsor

63.3

Hamilton

63

Niagara Falls–St. Catharines

63

Brantford

62

Kelowna

61

London

57

Ottawa

55

Toronto

54.5

Belleville

54

Lethbridge

54

Regina

54

Montreal

53.7

Kitchener–Cambridge–Waterloo

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO

The purpose of building codes is to set out the minimum standards to construct a safe building. Canada has a National Building Code, but it is only a template that provinces and territories use to enact their own binding codes. Some provinces adopt the national code in its entirety, while others add some modifications to draft their own rules. Municipalities can also have their own construction bylaws.

While building codes currently deal with immediate safety concerns, they have yet to address the growing impact of climate change, said Keith Porter, chief engineer with the insurance-industry-backed Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. “You don’t have short circuits that cause fires inside of your walls and your pipes don’t suddenly develop leaks that make them break – the code is good at that sort of thing. But it doesn’t consider your long-term costs for repairs after tornadoes and fires and so on,” he said.

“One of the issues that really stood out for me about the code is that heat is not considered an emergency,” says Joanna Eyquem, who develops programs to limit extreme heat risks for the University of Waterloo’s Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation.

She noted there are, for example, code requirements for emergency electrical power in case of fires “but there isn’t anything in there to keep essential systems like air conditioning running during a heat wave.”

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/ACFQAGE7FVKHHNPJUWHVNFVM7I.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/COKBVAZRA5GFFNXFVTXLWIGYXE.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LL7GD4LOGNFEHDKGKXYWMRJOEU.JPG)

Marianne Touchie, an associate professor with the University of Toronto’s civil engineering department, said that codes have not previously required mechanical cooling because, historically, Canada is a heating-oriented country. “We’re designed for cold weather,” said Dr. Touchie. “We haven’t adapted our building archetypes to address overheating.”

Also, the danger from extreme heat is different from other climatic threats such as tornadoes or flooding because high temperatures don’t immediately threaten the integrity of a building.

While extreme heat can affect the envelope of a building (such as claddings or doors), it does not have a significant impact on its structure, according to an analysis of the impact of climate change on public buildings released by the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario.

The humans inside those structures, however, are more vulnerable.

At the University of Ottawa’s Human and Environmental Physiology Research Unit, scientists have found that health problems may arise for some adults when the thermostat remains between 26 and 31 degrees for hours at a time, especially for high-risk people such as the elderly.

Dr. Touchie said a maximum indoor temperature should be written into building regulations.

The body's ideal internal temperature is 36.9 degrees. What happens beyond that point? Watch to learn more.

Potential cooling requirements cited in the B.C. coroner’s panel report include using materials that reflect the sun’s rays, pumps that extract the thermal energy from inside a building, and better insulation to maintain a safe temperature.

The B.C. ministry responsible for housing says the province has been working with the National Research Council (NRC) – the federal agency involved in code-making – to assess the risk of overheating in buildings and possible solutions.

“Work is under way nationally to develop standardized requirements to address overheating in new construction,” said Zachary May, executive director of the Building and Safety Standards Branch of B.C’s Ministry of Housing.

“The province of B.C. has advocated for prioritizing urgent action on the risks associated with overheating in buildings.”

Ms. Lalonde’s daughter, Christine, said she’s been brought a sense of relief that the coroner’s review included the new recommendation related to extreme heat.

“I’m glad something is coming of this,” she said. “That was a horrible event … Hundreds of families were impacted.”

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/PJ7HZALP2VGOXJYQF5IQB4GBSI.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LM2EX27ULJLITIAADG2GR3D25U.JPG)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/XB6DCJNBPNK5ZNCPSM5ABIZ4CE.JPG)

The NRC told The Globe in a statement that it had worked with standard-setting authorities to develop guidance for preventing overheating in buildings. The document lists measures such as window glazing, shading devices, ventilation, and reflective construction materials. However, the guidance is just that – guidance. It is not mandatory, nor is it written into the national code.

Updating building codes is a slow process. The next version of the national code is set for 2025 and it could take more than a year afterward for provincial and municipal authorities to update their own documents.

Already, some municipalities have moved forward with their own initiatives to reduce the impact of heat waves. In the wake of the heat dome, Vancouver city council adopted bylaws requiring cooling and air filtration in all new multi-family buildings by 2025.

Other cities also have construction rules aimed at reducing urban heat islands, the dense, built-up areas that typically lead to warmer air temperatures. Toronto and some of its suburbs, such as Ajax or Pickering, for example, have environmental standards, which, in addition to energy efficiency goals, also include a mix of mandatory and voluntary heat-related measures for new construction. Those municipalities’ mandatory standards usually require new buildings to have a roof made with materials that reflect rather than absorb the sun’s energy, or a green roof with vegetation that absorbs the heat.

Volunteer Paul Rowe assembles a fan last summer in Burnaby, B.C., for heat care packages destined for vulnerable seniors.Amy Romer/The Globe and Mail

Assisted-living facilities for elderly people are another type of building whose residents need to be shielded from extreme heat. Most provinces still don’t mandate air conditioning in long-term care accommodations.

In Ontario, however, nursing homes have been required since June, 2022, to have air conditioning in every resident’s room. The regulation is part of an overhaul that Ontario introduced after the COVID-19 pandemic exposed multiple weaknesses in its long-term care system. A government spokesman, Jake Roseman, said that 591 long-term care homes, 94 per cent of the province’s total, have complied so far.

In Quebec, the new generation of nursing homes, called Maisons des aînés (French for elders’ houses), require air conditioning in every room. But for seniors still living in the 22,700 bedrooms of the older Quebec nursing home models, only 46 per cent have air conditioning, according to AQRP, the association of retired Quebec public-sector workers, which obtained the data through access-to-information requests.

Like the B.C. coroner’s panel, the AQRP says that building codes need to incorporate passive and active cooling requirements, especially in nursing homes and low-income dwellings.

These stepwise efforts are happening while researchers warn that extreme heat will be a growing concern.

The World Weather Attribution project, an international scientific initiative that evaluates to what extent an extreme weather event is linked to climate change, has analyzed the B.C. heat dome. The project concluded that it was a once-in-1,000-years occurrence now made 150 times more likely because of human-caused climate change – meaning that it could happen roughly every five to 10 years in the future.

In a 2022 report titled “Irreversible Extreme Heat,” Ms. Eyquem’s research centre at the University of Waterloo warns that extreme temperatures will be an issue for decades to come. The centre projected that, even in a low-carbon scenario, by the middle of the century, the days over 30 degrees Celsius will triple in cities such as Toronto, Ottawa or Montreal.

“We cannot wait for the National Building Code,” Ms. Eyquem said. “We already had that huge heat dome event, and these events are getting more frequent and more intense. So, we can’t wait 10 years to have a building code that is good, to then start building things that are appropriate.”

Reader callout: Share your stories of extreme weather at home

Has your home been affected by extreme weather in Canada? The Globe wants to hear from you. Share your story in the box below or e-mail audience@globeandmail.com.

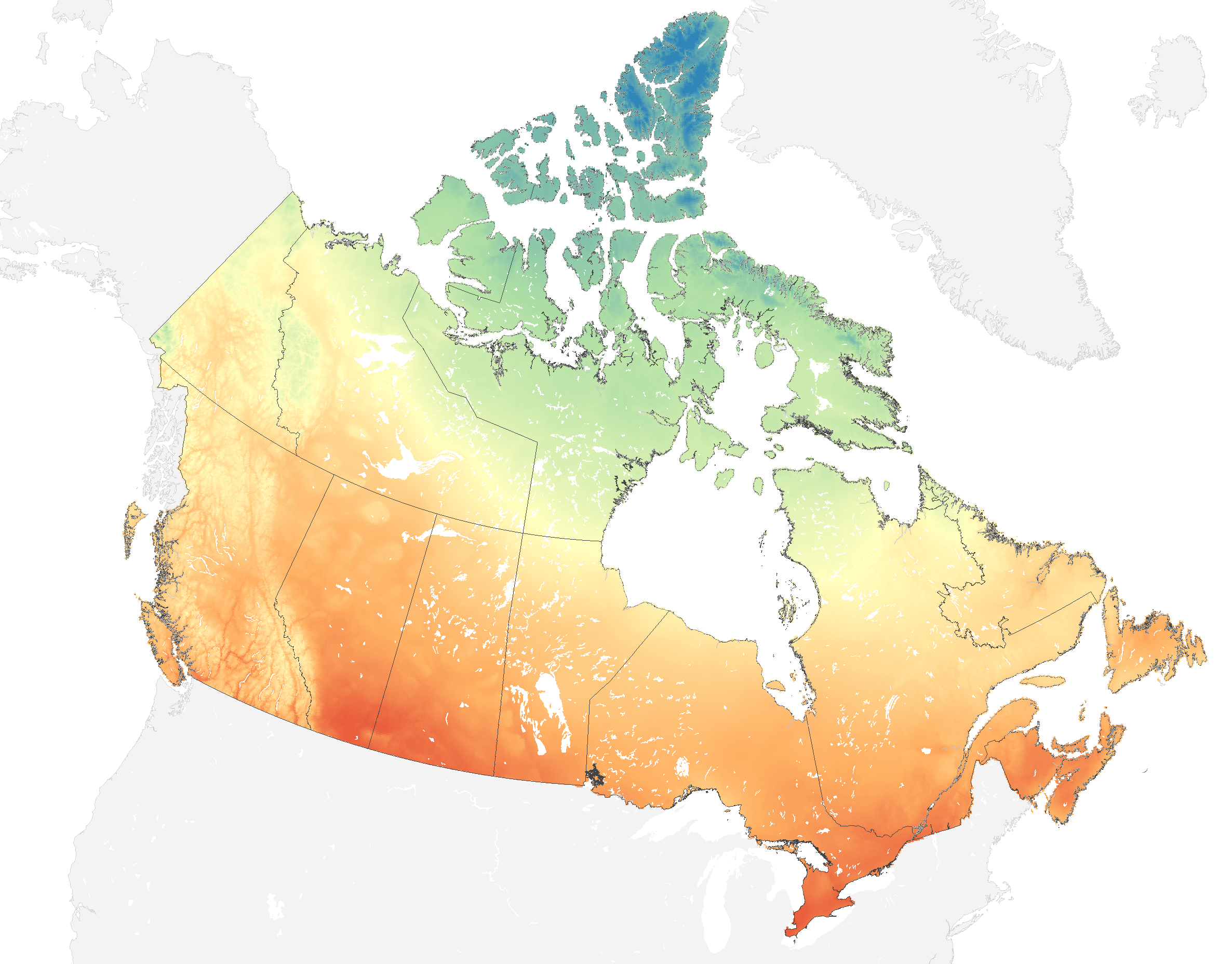

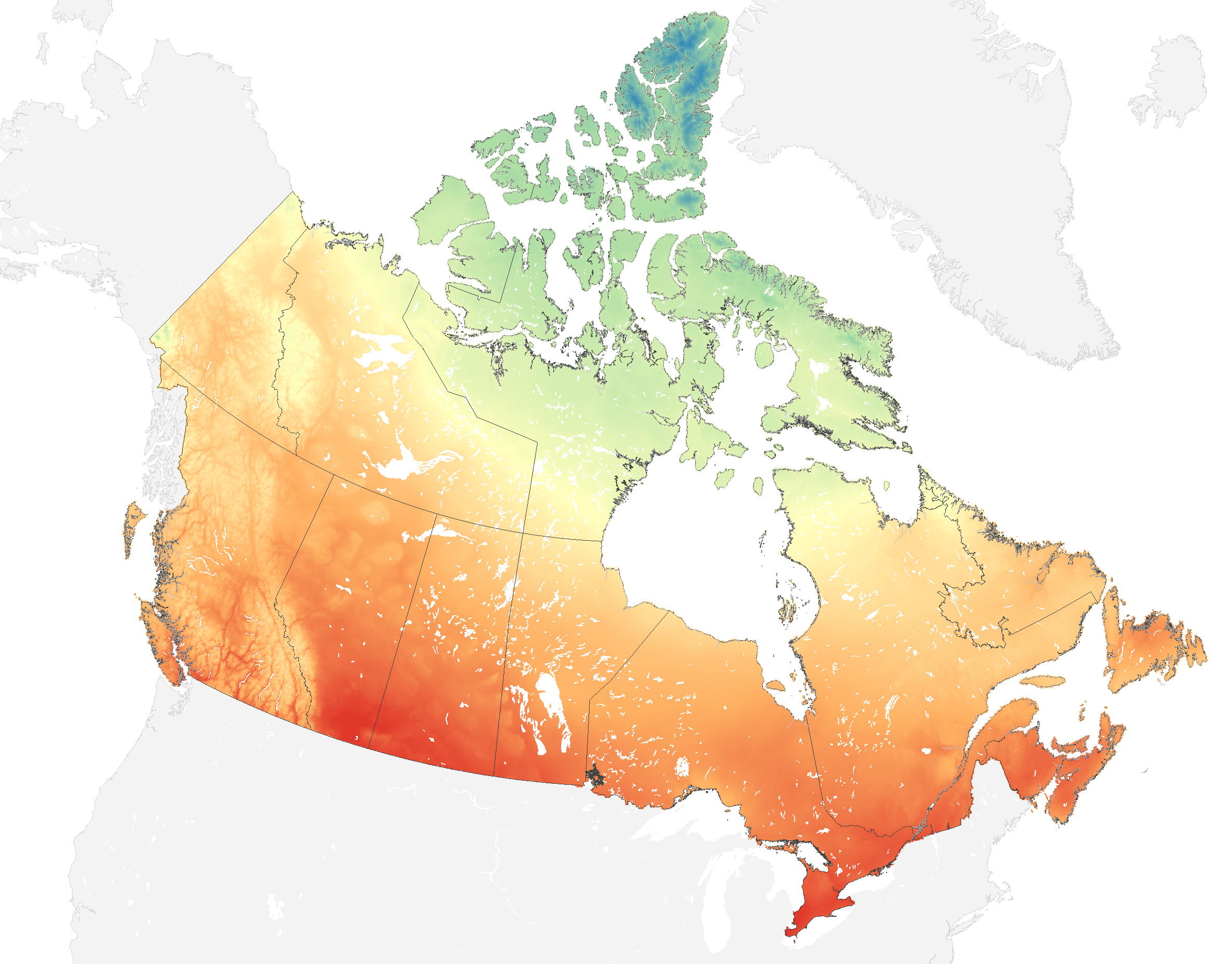

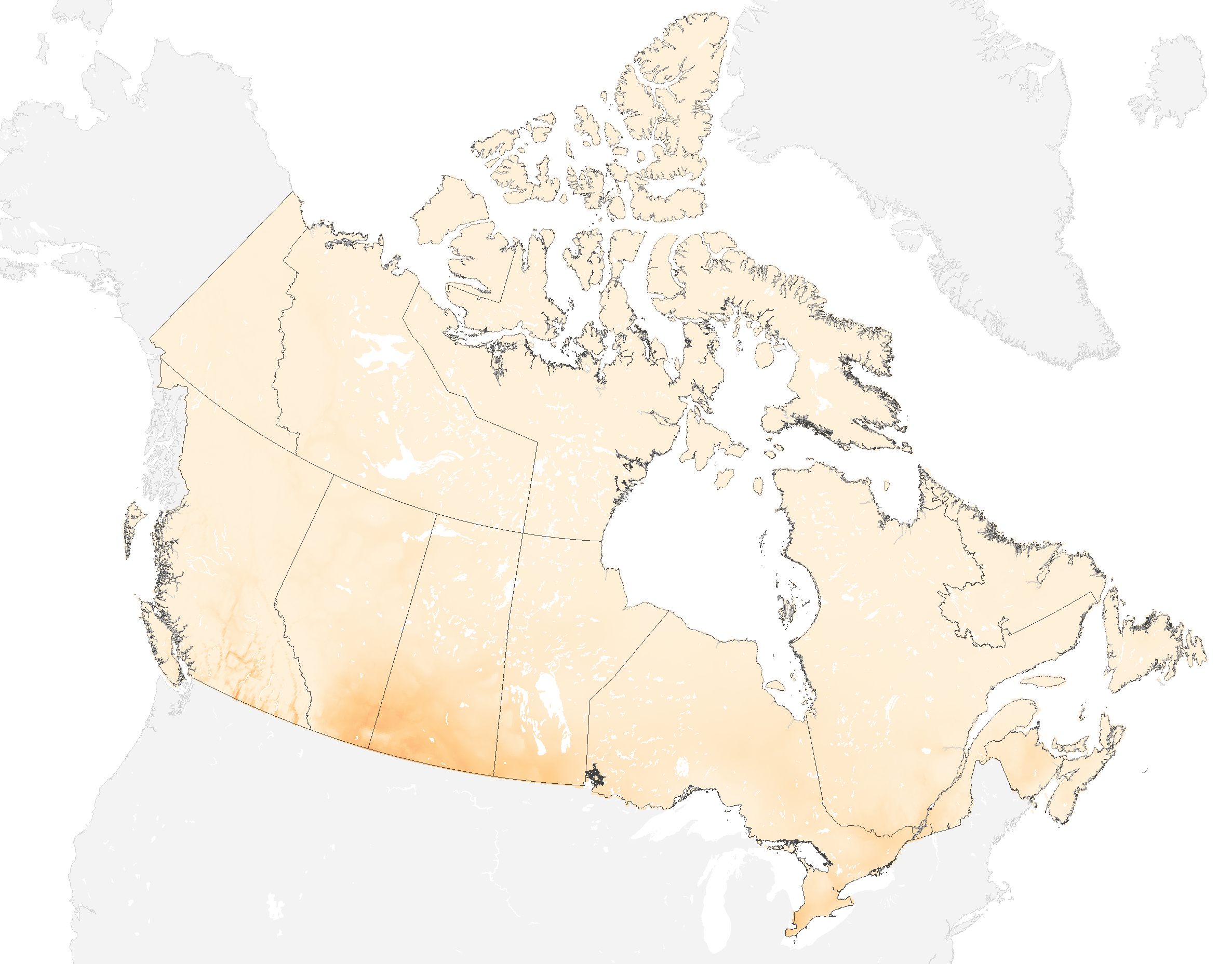

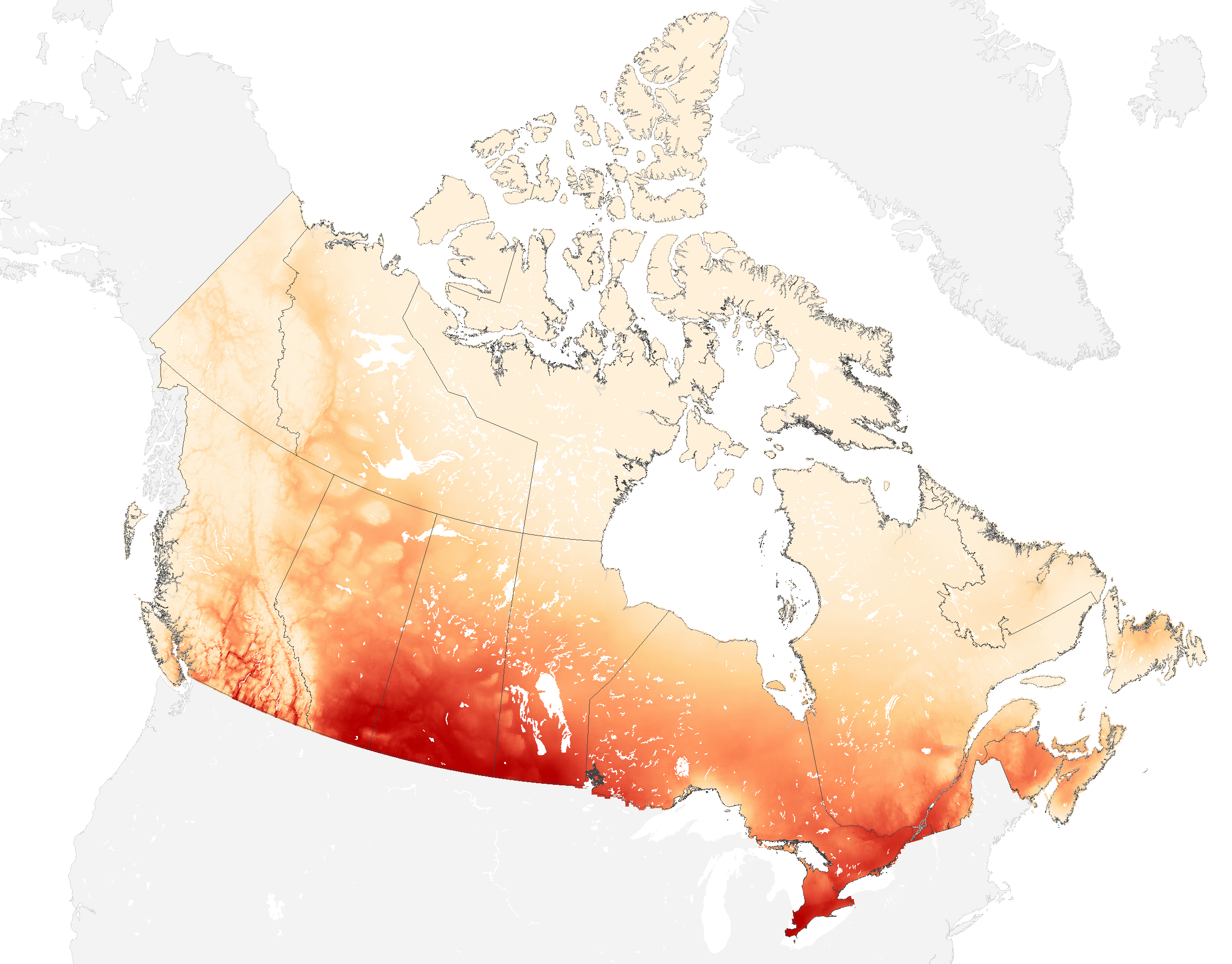

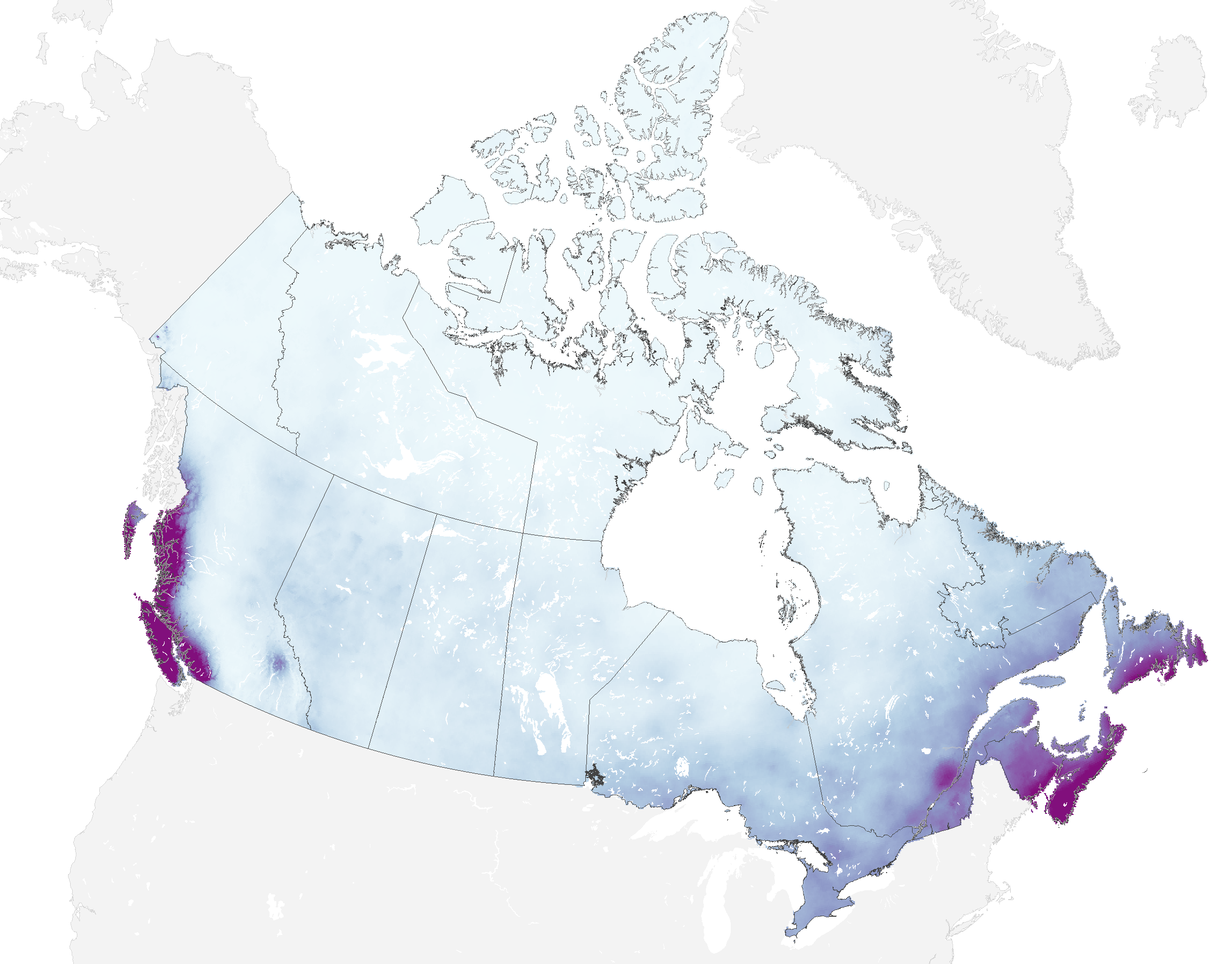

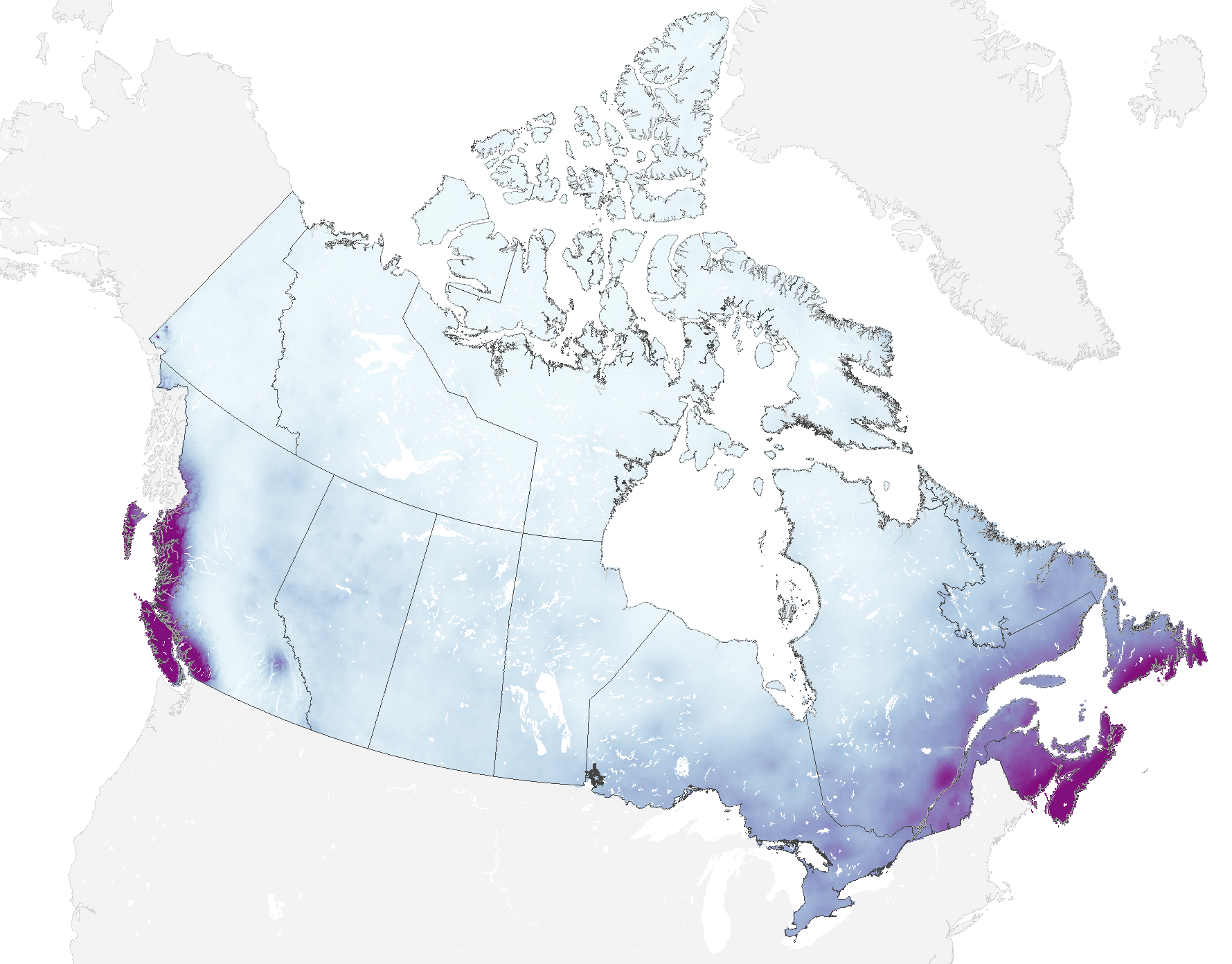

The heat is on: Canada’s direst climate-change scenario

Increasing heat and precipitation are two of the threats facing Canadians and their homes, depending on how well or poorly the world controls its greenhouse-gas emissions. Here’s what to expect in a high-emissions scenario, according to CMIP6, the latest version of one of the models for predicting future climate trends.

Choose a category and time period below to see some ways Canada's climate is projected to change in the near future

- -10

- 0

- 10

- 20

- 30

- 0

- 30

- 60

- 90

- 0

- 10

- 20

Canada and climate change: More from The Globe and Mail

The Decibel podcast

How did B.C.’s urban landscape make the 2021 heat dome so deadly, and what can be done to change it? It’s not just a matter of more air conditioning, Globe contributor Frances Bula explains to The Decibel. Subscribe for more episodes.

Code Minimum: More from this series

Why your home isn’t built to last against extreme weather

They waterproofed their homes. Quebec’s outdated building codes left them vulnerable

As tornadoes in Canada get more destructive, momentum builds for new building codes to save homes