Clint Randen's single-room occupancy unit at Vancouver's Flint Hotel was like 'a sauna' for days during June's deadly heat wave on the West Coast. He moved into a tent in a local park shortly after, looking for an escape from the heat.Jesse Winter/The Globe and Mail

More below • How 2021 broke the records for daytime heat

By the time the car pulled up to Vancouver’s Fire Hall No. 5 on the night of June 28, Assistant Fire Chief Brian Bertuzzi was already in crisis mode. It was 9:30 p.m., and the city was on its fourth day of an extreme heat warning, smouldering under temperatures so catastrophically unusual that even young, healthy people were vomiting, losing consciousness and struggling to breathe. Every fire truck in the city was out on medical calls; not a single station had a truck on hand in the event of an actual fire.

In the backseat of the car, someone was performing chest compressions on an elderly man in the hopes of restarting his heart. The family had tried to call for an ambulance but couldn’t get through to 911.

Chief Bertuzzi and a battalion chief pulled the elderly man onto the driveway and took over CPR. They cycled through several rounds of the defibrillator before Chief Bertuzzi ran into the firehall to get oxygen.

That’s when the station’s phone rang. “Sir! You need to help me! My mom is dying in the bathroom! I’m calling 911 and no one is answering,” a woman said. Chief Bertuzzi told the woman she’d have to keep trying. Just as he hung up, the phone rang again. “You’ve got to help me! My dad is dying on the kitchen floor! We can’t get through to 911,” a man said. Chief Bertuzzi told the caller to keep dialling and then ran back outside. It was about 20 minutes before an ambulance arrived. The elderly man was long dead.

“It was a war,” a still-shaken Chief Bertuzzi told The Globe and Mail, describing the chaos in Vancouver at the peak of the heat wave. “We did what we had to do. It was surreal.”

Helping to save Vancouverites from this past summer’s severe heat was a formidable challenge for Assistant Fire Chief Brian Bertuzzi and his team.Jesse Winter/The Globe and Mail

The June heat wave was the most deadly weather event in Canadian history, according to statistical analysis from the B.C. Centre for Disease Control. It’s also estimated to be a once-in-a-thousand-years event, made 150 times more likely due to human-caused climate change.

Preliminary data from the B.C. Coroners Service has found at least 569 people died in B.C. due to the extreme heat that settled over the Pacific Northwest for about a week. Hundreds more died in Oregon and Washington.

From June 24 to June 30, paramedics in B.C. responded to 772 cases specifically recorded as heat-related illness – 55 times the number logged during the entire month of June last year. Sixty-five per cent of patients were aged 60 and older. During the same seven-day period, the province’s 911 system answered 50,791 calls for help, marking an almost 50-per-cent increase over the same dates last year.

“The scary thing for me is that 20 years from now, we’ll look back at this moment as the cooler days – it’s only getting hotter,” said Eric Klinenberg, a professor of psychology at New York University and author of Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, about the 1995 extreme heat event that killed 739 people in the U.S. city. “It’s time for a reckoning.”

A man cools off at a temporary misting station on Vancouver's Downtown Eastside this past June.Darryl Dyck/The Globe and Mail

While heat doesn’t have the shocking visual impact of wildfires or floods, it’s one of the deadliest weapons in climate change’s arsenal. The heat wave that hit Europe in 2003 claimed the lives of an estimated 70,000 people.

In an average year, heat is the No. 1 weather-related killer in the U.S. Canada doesn’t have a national system for recording deaths from climate-change hazards – there’s too much inconsistency in reporting across jurisdictions – but the federal government says extreme heat is considered a leading cause of death among climate-change–related weather events.

July of 2021 was the world’s hottest month ever recorded, according to global data recently released by U.S. federal scientists. And unless we take steps now, heat will claim more lives as the Earth continues to warm.

Scenes like the ones that unfolded in B.C. in late June will repeat themselves in more and more communities, necessitating a wholesale rethink of how our emergency services operate, and how our cities and homes are built.

Heat also lays the groundwork for a cascade of other destructive forces. With heat comes wildfires, which can devastate communities, landscapes and critical infrastructure. And with fire comes smoke, which releases harmful particulate matter into the air we breathe.

It’s an economic issue too. The Canadian Institute for Climate Choices estimates that by the end of the century, climate-change-fuelled extreme heat could lead to an annual loss of 128-million work hours in Canada, at a cost of almost $15-billion per year.

Smoke fills the air in Monte Lake, B.C., at a property destroyed by this summer's White Rock Lake fire.Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

This summer, it was laid brutally bare for Canadians that while climate change is a global problem, its effects are local. Temperature norms and records were smashed by massive margins, including in Lytton, B.C., which hit 49.6C on June 29 – 23.5 degrees higher than the normal maximum for that time of year and 4.6 degrees higher than the previous national record. The next day, the village went up in the flames of a raging wildfire. The rest of the country was not spared. Across southern Canada, this summer will likely rank among the top five warmest seasons in 75 years.

According to Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Winnipeg saw a record 34 days above 30C, compared to an average of 13. Saskatoon had eight days above 35C; the norm is one. Montreal had its first heat wave before the summer even started; this August was the hottest on record. Toronto surpassed highs set decades ago. The northern Prairies baked at temperatures in the mid-30s. Typically temperate Atlantic communities were oppressively hot. Crops across the country were scorched and stunted.

Climate change was a top issue for voters in the recent federal election. With a new minority mandate, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Liberal government will have crucial and imminent work to do, not only in terms of mitigating warming but adapting to it. The June heat wave proves the point. Built for a world we no longer live in, transit infrastructure melted, drawbridges malfunctioned, roads buckled, and power grids failed.

“In some ways, it was extreme, but it’s a classic example of what happens in a well-resourced area that’s unprepared,” said University of Washington global health professor Kristie Ebi, a lead author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2018 special report about the impacts of global warming of 1.5C above preindustrial levels.

“This is where you go to discussions around a tipping point – the accumulation of information, the accumulation of events. Are we at a moment where there’s sufficient weight that there’s a real shift in people’s understanding about climate change?”

An emergency worker treats a person for heat-illness symptoms in Portland, Ore., this past August. The U.S. city was among the places hardest hit by the Pacific Northwest heat wave in June. Oregon's mortality rate was far lower than in B.C., in part due to much higher rates of air conditioning – which, as noted in the chart below, can make the difference between manageable and dangerous indoor heat.Tojo Andrianarivo/The New York Times

INDOOR TEMPERATURES IN TWO HOUSES IN ABBOTSFORD, B.C. DURING THE HEATWAVE

In Celsius

House without

air conditioning

House with

air conditioning

40°C

30

20

10

7

June

24

27

29

July

1

3

5

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ANONYMIZED DATA FROM ECOBEE DONATE YOUR DATA PROGRAM, B.C. CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL

INDOOR TEMPERATURES IN TWO HOUSES IN ABBOTSFORD, B.C. DURING THE HEATWAVE

In Celsius

House without

air conditioning

House with

air conditioning

40°C

30

20

10

7

June

24

27

29

July

1

3

5

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ANONYMIZED DATA FROM ECOBEE DONATE YOUR DATA PROGRAM, B.C. CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL

INDOOR TEMPERATURES IN TWO HOUSES IN ABBOTSFORD, B.C. DURING THE HEATWAVE

In Celsius

House without air conditioning

House with air conditioning

40°C

30

20

10

7

June

24

27

29

July

1

3

5

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ANONYMIZED DATA FROM ECOBEE DONATE YOUR DATA PROGRAM, B.C. CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL

The temperatures seen in Canada this year weren’t projected to materialize until well into the second half of the century. And because the extreme heat started in June – not July or August, as is typical – it was also more fatal; the body acclimates to higher temperatures as the summer goes on, so it’s more vulnerable to system failure at the outset of the season.

The situation is going to get worse. The latest IPCC report, released last month and billed by the United Nations Secretary-General as a “code red for humanity,” said the global average temperature will likely exceed the 2015 Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming threshold in the next 20 years. The report warns that every additional half-degree of warming causes “clearly discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes.”

This has implications for all life on Earth. More than one billion sea creatures along Vancouver’s coast were cooked to death during the June heat wave. Trees shed their leaves prematurely, laying a crispy green and brown carpet on sidewalks and roads.

Humans were pushed past their limits. The body functions best at a core temperature of around 37C. If that temperature reaches 40C and continues to warm, critical systems start shutting down. The brain stops processing normally. The body loses its ability to thermoregulate through sweating. The blood thickens, forcing the heart to beat harder and faster. Breathing becomes rapid and shallow. Organ systems eventually fail.

Watch: The body's ideal internal temperature is 36.9 degrees. What symptoms appear when it's pushed beyond those limits, and how can people stay safe from the effects of heatstroke?

Particularly vulnerable to this sort of demise are the young and elderly, those with chronic heart or lung conditions, those with mental illness or mobility issues, those who live alone and are socially isolated, and people experiencing homelessness or of lower socio-economic status.

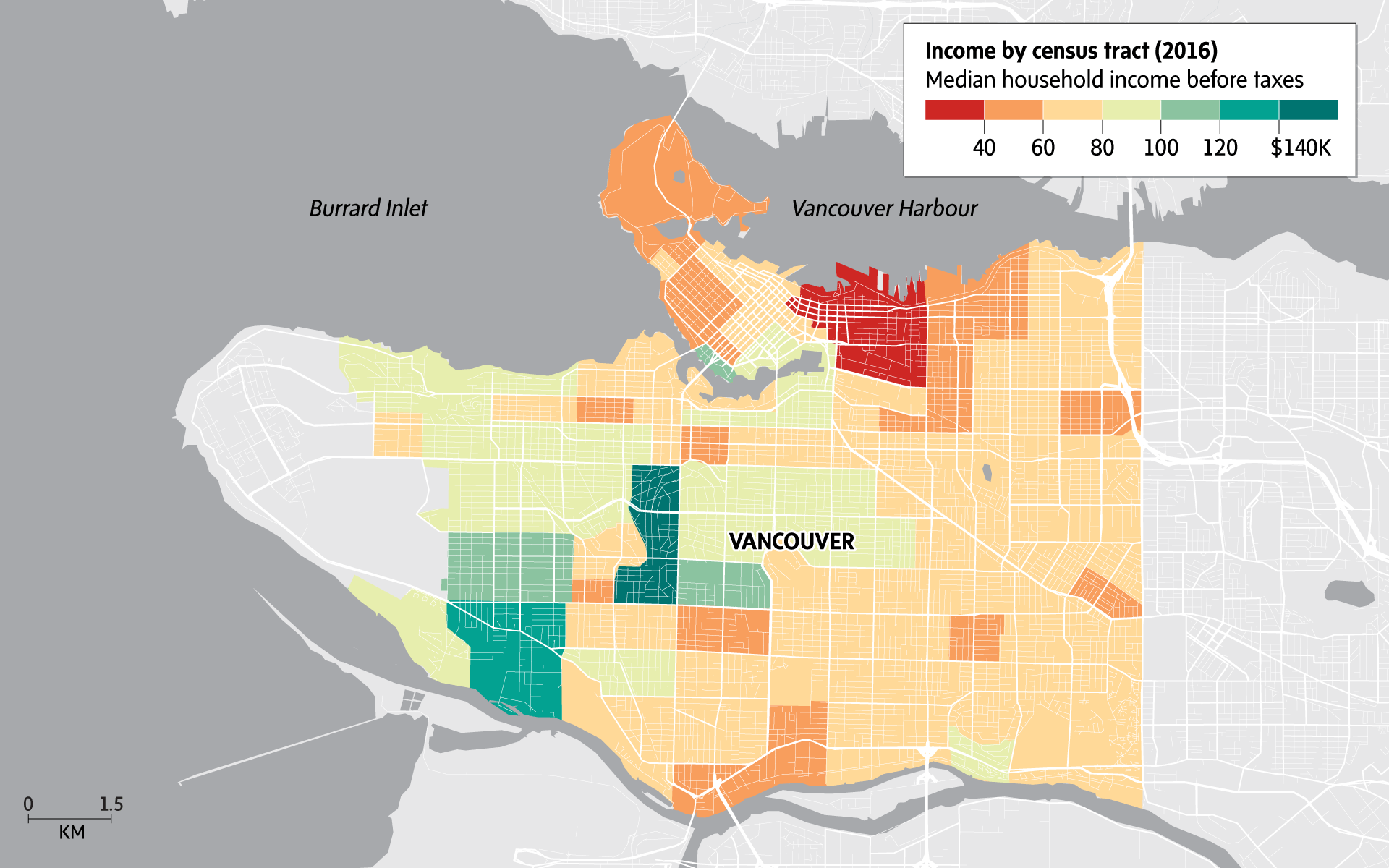

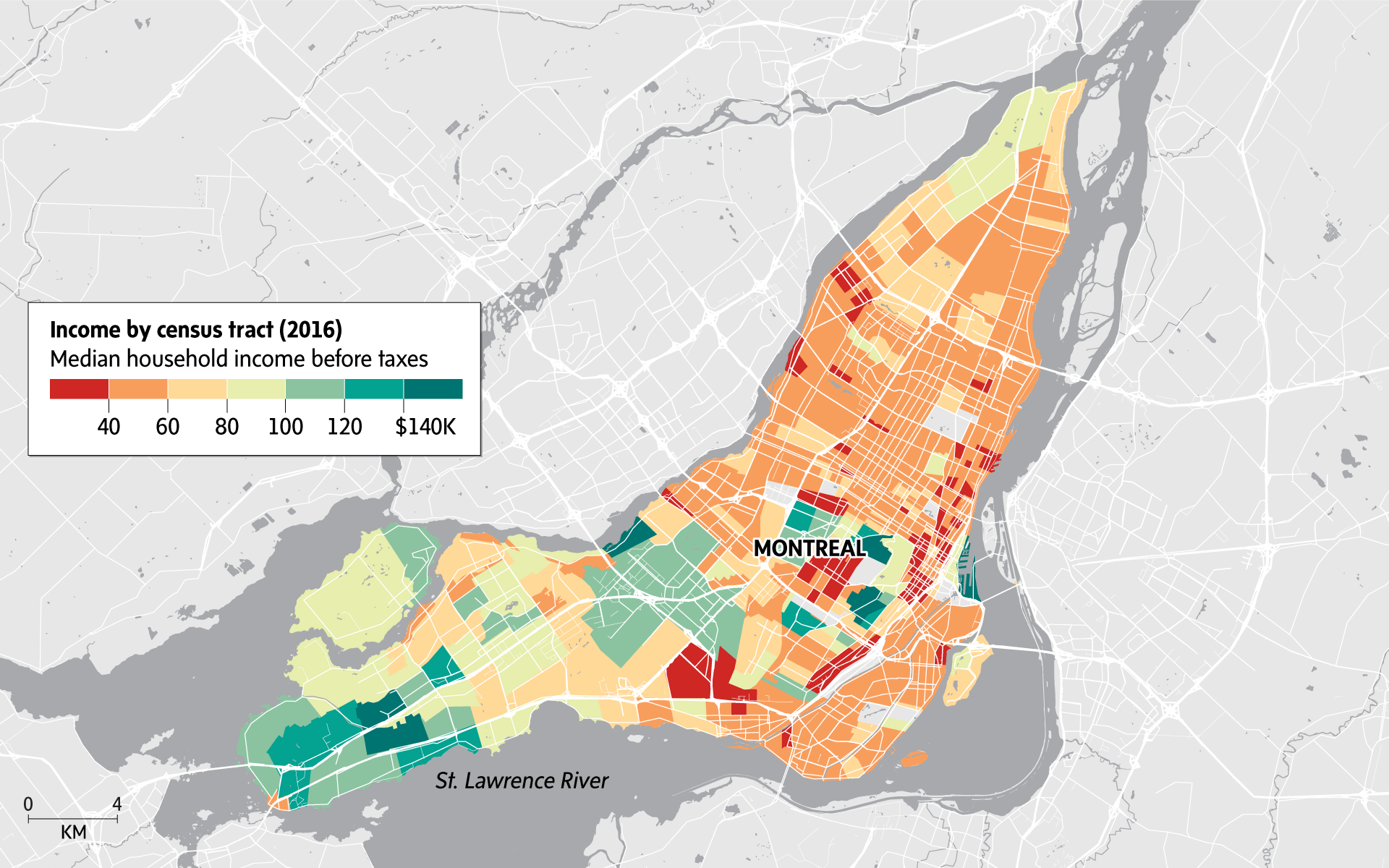

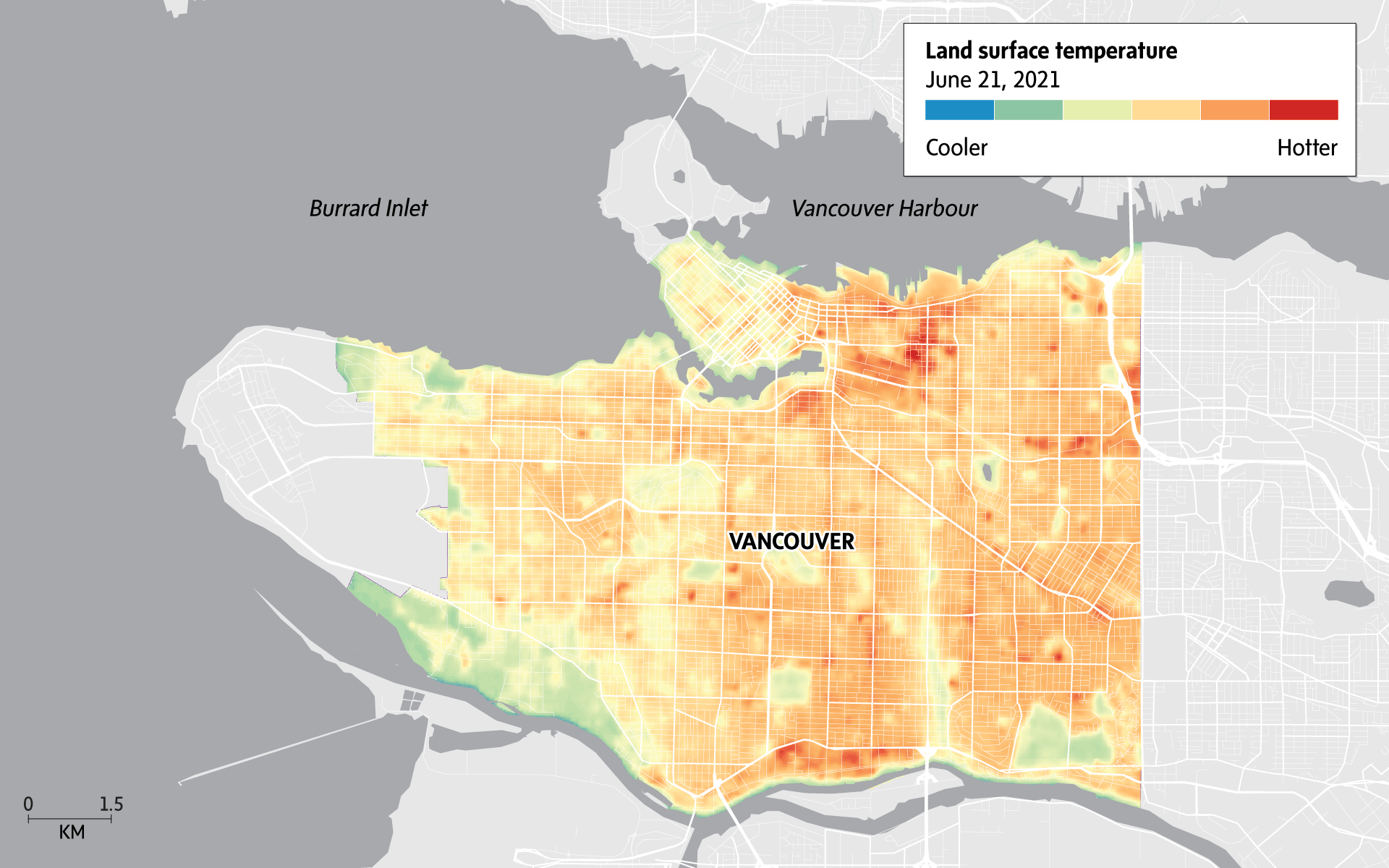

Indeed, there’s a link between income and land-surface temperatures: Poorer neighbourhoods with less natural vegetation and fewer green spaces are often several degrees warmer than richer ones. This is due to the urban heat island effect – a phenomenon first documented in the early 1800s in which artificial surfaces such as concrete absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes, causing localized warming.

In the wake of the June heat wave, the B.C. Coroners Service is leading a review of how the province handled the extreme event. The Vancouver fire department is canvassing officers for input on what could have been done better. So too is the union representing B.C.’s paramedics and dispatchers.

The City of Vancouver is undertaking a review of its emergency management strategies and heat response plan. The province’s largest 911 centre, which handles 99 per cent of calls, is doing an internal review of staffing practices. Health Canada is communicating with authorities in B.C. to learn from their experiences and will share these lessons with public health officials across the country.

What’s already clear from the June heat wave, though, is that multiple authorities were caught off-guard by the heat-induced mayhem. Interviews with residents, community leaders, front-line workers, scientists, sociologists and government officials illustrate that while people knew the heat wave was coming and took steps to mitigate it, no one was properly prepared for so many people to get so sick, so quickly.

As the world warms, more extreme heat is coming. Will Canada be ready?

High heat’s impact on the rich and poor

Lower-income neighbourhoods with less vegetation and more heat-absorbing concrete are often at higher risk of becoming ‘heat islands.’ In the maps below, see how the income of neighbourhoods in Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal compare with the temperatures on hot summer days.

The last time Christine Lalonde spoke with her 74-year-old mother, Roberta “Bunny” Lalonde, was at the beginning of the week of June 21. The two women were rebuilding their relationship after more than a decade of estrangement.

Bunny lived alone in a condo in Chilliwack, B.C., about 100 kilometres east of Vancouver. She was on a low dose of anti-cholesterol medication but was otherwise in good health. She was planning on flying to Ontario to visit her daughter in the fall; it would have been the first time they’d seen each other in 12 years.

As the week went on, ECCC released increasingly strongly worded heat statements warning a high-pressure system would bring the hottest temperatures B.C. and southern Yukon had seen to date. Known as a heat dome, the atmospheric juggernaut would effectively act as a convection oven, relentlessly circulating hot air over the Pacific Northwest.

Environment Canada heat thresholds vary by location, in part because people who live in typically warmer areas can withstand higher temperatures than those who don’t. For most of Canada, a heat warning will be issued if two or more consecutive days of heat conditions are forecast to meet or exceed a maximum daytime temperature and remain above a minimum temperature overnight.

This is because the effects of excessive natural heat build up over time. If the human body is given an opportunity to cool down, even briefly, it has a better chance of fending off heat-related illness. But evening temperatures in B.C. in late June were forecast to offer little reprieve. Only about a fifth of households in the Vancouver region had air conditioning in 2017, according to the most recent Statistics Canada data – well below the national rate of about 60 per cent.

Bunny Lalonde’s condo didn’t have air conditioning.

Roberta (Bunny) Lalonde lived in a Chilliwack condo without air conditioning when B.C.'s heat wave hit.Courtesy of Christine Lalonde

Following a June 23 federal heat warning for the period beginning June 25, B.C.’s E-Comm system, which provides dispatch services for police and fire departments, sent out overtime requests for the upcoming weekend of June 26–27 and through the following week. On June 24, the City of Vancouver’s emergency management team held a call with staff, the Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) authority and ECCC to co-ordinate the city’s response.

The city released a media bulletin about access to cooling centres, water fountains and misting stations. Municipal officials also requested that the operators of single-room occupancy hotels, which house people at risk of homelessness in the Downtown Eastside, Chinatown and Gastown areas, check on vulnerable residents.

Clint Randen, who lives in the Flint Hotel near the Downtown Eastside, said his room felt like a sauna, even at night. And when he went outside to scrounge for scrap metal, cans and bottles, he passed out multiple times from the heat. Another Flint resident, Art Palmer, said it was so hot in the building that “you couldn’t even get your breath.”

Meanwhile, the gates of nearby Oppenheimer Park – which had been closed since May, 2020, when the city removed a large tent city – remained locked due to restoration work. Amid public criticism and a day ahead of schedule, the park’s phased reopening began on June 28.

Among those advocating to reopen the park was Janice Abbott, the CEO of Atira Women’s Resource Society and Atira Property Management, which runs 40 low-income buildings in the Downtown Eastside. “Given what we knew was coming, it felt like the wheels were turning very slowly,” she said. “There’s hardly any trees or parks in the area, and that all contributes to this unfriendly, concrete death and health trap.”

On Friday, June 25, E-Comm received 6,898 calls – an increase of nearly 800 over the previous day. The City of Vancouver rolled out its Level 1 heat response, which includes opening cooling centres and wading pools, installing misters, distributing bottled water to community centres and directing Park Rangers to look out for people showing signs of heat exhaustion.

That evening, VCH issued an extreme heat alert, indicating the high temperatures were expected to cause an increase in mortality. In response, the City of Vancouver extended the hours at some cooling centres, added heavy misters in the Downtown Eastside and opened pop-up spray locations in 15 parks.

Over the weekend, with temperatures hitting the mid-40s in some places, paramedics responded to more than 200 cases recorded as heat-related illness in just two days – 14 times the number logged over the entire month of June last year.

With the humidity, it felt like 44C in Chilliwack, where Bunny Lalonde lived. Her son tried to convince her to take an air-conditioned drive to his home in Langley, B.C., which has a pool. The 74-year-old declined. “My mom was a bit stubborn,” Christine Lalonde said. “She probably thought it’d be fine … I don’t know if she really knew the effects that heat like that can have on the body.”

June 28 was an especially tough day for Chief Bertuzzi and the 142 firefighters on duty, as heat-related medical emergencies flared up across Vancouver.Jesse Winter/The Globe and Mail

At 8 a.m. on Monday, June 28, Chief Bertuzzi started his 24-hour shift as the assistant fire chief on duty for all of Vancouver. It would be the most stressful day of his career. The city’s 142 on-duty firefighters would be stretched to their limits, tending to patients needing paramedic care and waiting with dead bodies, sometimes for hours, for a coroner to relieve them.

So many people were dying that the B.C. Coroners Service redeployed all available coroners to the frontlines regardless of whether they were field coroners, who attend the scene of deaths, or investigating coroners, who determine the circumstances surrounding the deaths.

Dying people couldn’t get through to 911, since most E-Comm call-takers were tied up trying to transfer calls to the B.C. Emergency Health Services (BCEHS) ambulance service. Typically it takes five seconds or less to get through to 911. That Monday, one caller was on hold for 17 minutes.

With paramedics overwhelmed, fire crews were dispatched to medical calls. Patients were presenting with severe dehydration and life-threatening core body temperatures. Firefighters administered oxygen and cold compresses. They saved a lot of lives that night, Chief Bertuzzi said, but some people died waiting for medical care his crews just couldn’t or aren’t authorized to provide. Fire trucks aren’t licensed to transport people to the hospital, he noted, so in some cases crews loaded patients into taxis or private vehicles and then followed them to the hospital to make sure they were admitted. (Since the heat wave, the province has directed the licensing board to examine expanding firefighters’ scope of practice.)

Demand for fire crews eased up briefly around the dinner hour, allowing firefighters to get back to their stations and restock with medical supplies. But by early evening, with temperatures in the low 40s in Vancouver, demand went through the roof. “Every fire truck in the city was out,” Chief Bertuzzi said. “In my 30 years, I’ve never seen all 142 on-duty firefighters at medical calls.”

At Firehall No. 5, Chief Bertuzzi had to help treat an elderly man in cardiac arrest whose family brought him there in desperation.Jesse Winter/The Globe and Mail

At around 8 p.m., his cell started ringing with calls from firefighters who were running out of oxygen. Chief Bertuzzi picked up about three dozen empty oxygen bottles and headed to the refilling station at Firehall No. 5. He was in the middle of exchanging empty bottles for full ones when the car pulled up with the elderly man in cardiac arrest.

“We live in a privileged country, where these things aren’t supposed to happen,” Vancouver Fire Chief Karen Fry said. “You’re supposed to call 911 and help is supposed to arrive.” At one point, Chief Fry called her elderly parents and told them that if they needed medical attention, they should go get help because help might not come to them.

While the battalion chief was performing CPR on the elderly man, Chief Bertuzzi radioed Vancouver fire dispatch to report a full cardiac arrest. Under BCEHS’s clinical response model, each case is assigned one of six colours, ranging from purple, for immediately life-threatening cases, to blue, for cases that could be referred to a nursing line. The man’s case would have been coded as purple. It still took 20 minutes for a first responder to arrive, Chief Bertuzzi said. It would be another five hours before a coroner showed up.

Troy Clifford, the president of the union representing more than 4,400 paramedics and emergency dispatchers in B.C., said that at the height of the chaos, some purple calls waited over an hour. The heat wave, he said, exposed existing vulnerabilities in the province’s emergency system, including labour shortages. He said that even as people waited for paramedics, ambulances sat empty because there weren’t enough people to operate them. “It was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” he said, noting the extreme temperatures came just as the province was reopening from COVID-19 restrictions and over a long weekend, when call volumes tend to be higher.

The province, Mr. Clifford added, could have exercised its power to recall off-duty paramedics and dispatchers but didn’t. Minister of Health Adrian Dix has since announced the government would hire an additional 85 paramedics and 30 dispatchers.

Strain on one lever of the emergency system has a ripple effect. On June 28, fire crews responded to almost 250 medical calls, compared to a daily average of 67, Chief Fry said. On a typical day, firefighters would wait between five and 10 minutes for paramedics to relieve them. But at 11:20 p.m. on June 28, she noted that 17 of 35 fire crews had been waiting more than an hour. One crew had been waiting four hours and 52 minutes. “We knew at that point that this was extreme, and we needed to do something about it,” Chief Fry said. “We would have had to abandon patients to respond to a fire. That’s a very difficult position to put our firefighters in.”

Just before midnight, Chief Fry convened an emergency meeting to develop a strategy for getting through the rest of the heat wave. She opened a departmental operations centre at Fire Hall No. 1, Vancouver Fire’s main headquarters, and brought on about 20 off-duty firefighters. The department decided to hold back at least a couple of trucks to deploy in the event of a fire. Sure enough, on the morning of Tuesday, June 29, a wildlands fire broke out on the city’s west side. Multiple trucks were deployed. No patients were abandoned.

Mr. Randen, top, and Art Palmer, bottom, say the Flint Hotel was unbearably hot in June.Jesse Winter/The Globe and Mail

On the afternoon of June 29, Christine Lalonde received a call from her sister-in-law, asking if she’d spoken with Bunny. The 74-year-old hadn’t been active on Facebook, which was unlike her.

Christine asked her uncle, who lived in the same building as Bunny, to check on her. He let himself into her unit and found Bunny, lifeless on her bed. “He said, ‘She’s dead, Christine. She’s dead,’” Christine recalled her uncle telling her. “It was devastating. The shock of it. I thought she was just sitting crankily in front of the fan.”

Bunny had turned on a couple of pedestal fans and opened her patio doors and windows. It’s unclear whether that would have done more harm than good. The prevailing public health advice is that fans are helpful when circulating air that’s cooler than the person’s body. But when the air is hotter, fans can actually cause a person to gain heat rather than lose it.

Bunny’s death certificate says she died on June 27.

A note from Bunny Lalonde's condo board offers condolences to her family.Courtesy of Christine Lalonde

According to the B.C. Coroner’s Service, 301 people died suddenly on June 29 alone – the deadliest day of the heat wave. That night, the Island Health authority sent a memo to several hospitals, saying acute-care centres had reached “extremely high patient volumes” and asking staff to cancel holidays, limit unplanned absences and take extra shifts.

The number of deaths in the province declined to 124 on June 30, still about three times the number of mortalities on the same day last year. The federal environment department and VCH wouldn’t rescind their heat warnings until July 2.

Melissa Lem, a family doctor in Vancouver and incoming president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment (CAPE), had never seen such a high volume of heat-related illnesses. In fact, she wasn’t aware there’s an international code used specifically to classify medical incidents related to exposure to excessive natural heat – X30 – so the sick patients she saw were coded for other ailments, such as headaches.

The way patient encounters are coded has implications for data-gathering. In the wake of the heat wave, the federal Climate Change and Innovation Bureau, part of Health Canada’s surveillance and monitoring section, reached out to CAPE, saying it was working to develop tools and applications to improve the collection of data associated with climate change and raise awareness about the applicable diagnostic codes.

Dr. Melissa Lem works in an exam room at her Vancouver clinic.Jesse Winter/The Globe and Mail

Dr. Lem’s practice is in Kitsilano, one of Vancouver’s most expensive neighbourhoods. It’s also one of the city’s coolest neighbourhoods. Situated along the south shore of English Bay, Kitsilano has 17 parks and one of Vancouver’s most popular beaches.

Just seven kilometres east is the Downtown Eastside. Data from a June 21 satellite image shows that land surface temperatures in this neighbourhood were more than four degrees warmer than in Kitsilano. When The Globe toured a single-resident occupancy hotel in the Downtown Eastside on a relatively cool day earlier this month, even a room with windows that opened onto the street was unpleasantly hot. In most cases, these units don’t have access to that kind of airflow – typically the windows open just a few inches, into a lightwell of stagnant air. When a second heat wave hit Vancouver in August, Mr. Randen left his Flint Hotel unit to sleep in a tent in a park.

As Ms. Abbott, the CEO of non-profit Atira, put it, “the buildings just are not designed to deal with hot weather.”

This is also true, to some degree, of buildings and homes in the wealthiest Vancouver neighbourhoods. Because summers there are typically temperate, the vast majority of residents don’t have air conditioning. This is not the case in Portland, Ore., which was also hit by the June heat dome but had a lower mortality rate. About 80 per cent of Portland households have air conditioning.

But as is the case with other climate-change challenges, one solution can bring new problems. Increasing access to air conditioning will inevitably increase the strain on power grids. And in areas that depend on highly polluting energy sources, additional capacity will lead to increased greenhouse-gas emissions. And so the cycle of warming continues.

Janice Abbott of Atira Women’s Resource Society stands in Oppenheimer Park on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Public spaces, especially those with natural shade to mitigate the heat, are crucial for poor residents whose housing isn't well ventilated.Jesse Winter/The Globe and Mail

Cities have long dedicated resources to protecting residents from floods or wildfires. Heat should be no different, according to Ladd Keith, a University of Arizona assistant professor of planning. “We should treat heat as a hazard,” Dr. Keith said. Heat governance, as he calls it, is necessary for tackling acute heat events as well as day-to-day chronic heat, which can be even more deadly than heat waves.

It’s no surprise that hot places such as Phoenix, which has a new permanent Office of Heat Response and Mitigation, or Florida’s Miami-Dade County, which this spring appointed the world’s first Chief Heat Officer, are leading the way in heat governance. But it’s not just warmer cities that are growing increasingly concerned.

Since the June heat dome, Dr. Keith has been getting calls from municipal officials in northern U.S. states, asking for advice on how to improve their heat preparedness and response. Some officials wondered, for example, whether renters should be guaranteed reprieve from heat in the summer just as they’re guaranteed reprieve from cold in the winter. In Dr. Keith’s Tuscon, housing regulations stipulate maximum indoor temperatures.

Tucson’s thresholds are for dry heat. For regions with higher moisture levels, the limits should take into account humidity, Dr. Keith said. That’s because the body’s ability to cool itself is much diminished when moisture in the air prevents sweat from evaporating.

Humidity, though, is hard to forecast. Even Quebec’s sophisticated heat-warning system doesn’t take it squarely into account, said Fateh Chebana, a professor and data scientist with the Institut national de la recherche scientifique. But the system does divide the province into four classes, each with its own temperature thresholds based on historical excess-mortality data. Now, Prof. Chebana is working on an even more advanced iteration of the system, slated to be piloted in the Montreal region next year. Its key feature will be thresholds that vary by month, to acknowledge that people are less acclimated to heat earlier and later in the year.

Indoor temperatures matter, too. Anonymized, voluntarily provided data collected from users of ecobee smart thermostats in Abbotsford, B.C., shows that the hottest home without air conditioning was nearly 17 degrees hotter at the peak of the June heat wave than the coolest home with air conditioning. There were also times when it was cooler outside than it was in the hottest residence without air conditioning. When it comes to indoor temperatures, there’s limited public health guidance on how high is too high. “Health Canada is working with researchers to identify safe indoor temperature thresholds for specific vulnerable groups, like seniors,” the federal department said in an e-mail.

A man playing guitar sits in the shade at Oppenheimer Park on June 28 after it was reopened to the public.Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press

Cities must also work to reduce the urban heat island effect. Tuscon, for example, is experimenting with lighter pavement coatings that, in theory, absorb and re-emit less solar energy. Cities can also protect their natural assets, such as river valleys and tree canopies, which provide cooling benefits.

In a report to be released later this month, the University of Waterloo’s Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation projects that three key areas in Canada will be hardest hit by extreme heat during the period of 2051-2080: valleys between the West Coast and the Rocky Mountains in B.C.; Prairie communities bordering the U.S.; and the area north of Lake Erie through the St. Lawrence River Valley in Ontario and Quebec.

The centre suggests a number of behavioural changes and natural solutions for adapting to extreme heat. It also makes recommendations for built infrastructure, including enhancing insulation, glazing windows with a heat-resistant coating, and designing new buildings to maximize passive cooling and encourage air flow. The federal government is already undertaking a national infrastructure assessment. Infrastructure Canada said research-based guidance will be released shortly to ensure new and retrofitted buildings are resilient to extreme heat events and provide safe conditions during heat waves. New federal research will also address overheating in public transit, including subway tunnels and trains.

For Dr. Keith, the time to start adapting was yesterday. Maybe this summer’s record-breaking temperatures will finally convince us to take heat seriously. “This was a landmark summer,” he said. “We’re already so far behind in planning for heat, compared to other hazards. We’re at risk of repeating mistakes next summer if we don’t catch up quickly.”

With a file from Jesse Winter in Vancouver

How 2021 broke the records for daytime heat

HIGHEST RECORDED DAYTIME

TEMPERATURES IN WESTERN CANADA

The extreme heat event across northwestern North America in late June was one for the record books. It broke so many records, in fact, that it’s difficult to keep track of them all. Notably, data from Environment and Climate Change Canada reveals that all-time records for maximum temperature were broken in 62 locations in Western Canada. Below, the five highest temperatures are plotted for selected locations. A striking number occurred during the event (plotted in purple).

Record broken in summer, 2021

BRITISH COLUMBIA

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Lytton

Cache Creek

Kamloops

Lillooet

Kelowna

Osoyoos

Clearwater

Trail

Summerland

Merritt

ALBERTA

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Grande Prairie

Jasper

Beaverlodge

Drumheller

Mildred Lake

Fort McMurray

Lethbridge

Red Earth Creek

Fort Chipewyan

Peace River

SASKATCHEWAN

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Elbow

Saskatoon

Lucky Lake

Kindersley

Stony Rapids

North Battleford

Southend Reindeer

Uranium City

Meadow Lake

Collins Bay

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE CANADA

HIGHEST RECORDED DAYTIME

TEMPERATURES IN WESTERN CANADA

The extreme heat event across northwestern North America in late June was one for the record books. It broke so many records, in fact, that it’s difficult to keep track of them all. Notably, data from Environment and Climate Change Canada reveals that all-time records for maximum temperature were broken in 62 locations in Western Canada. Below, the five highest temperatures are plotted for selected locations. A striking number occurred during the event (plotted in purple).

Record broken in summer, 2021

BRITISH COLUMBIA

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Lytton

Cache Creek

Kamloops

Lillooet

Kelowna

Osoyoos

Clearwater

Trail

Summerland

Merritt

ALBERTA

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Grande Prairie

Jasper

Beaverlodge

Drumheller

Mildred Lake

Fort McMurray

Lethbridge

Red Earth Creek

Fort Chipewyan

Peace River

SASKATCHEWAN

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Elbow

Saskatoon

Lucky Lake

Kindersley

Stony Rapids

North Battleford

Southend Reindeer

Uranium City

Meadow Lake

Collins Bay

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE CANADA

HIGHEST RECORDED DAYTIME TEMPERATURES IN WESTERN CANADA

The extreme heat event across northwestern North America in late June was one for the record books. It broke so many records, in fact, that it’s difficult to keep track of them all. Notably, data from Environment and Climate Change Canada reveals that all-time records for maximum temperature were broken in 62 locations in Western Canada. Below, the five highest temperatures are plotted for selected locations. A striking number occurred during the event (plotted in purple).

Record broken in summer, 2021

BRITISH COLUMBIA

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Lytton

Cache Creek

Kamloops

Lillooet

Kelowna

Osoyoos

Clearwater

Trail

Summerland

Merritt

ALBERTA

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Grande Prairie

Jasper

Beaverlodge

Drumheller

Mildred Lake

Fort McMurray

Lethbridge

Red Earth Creek

Fort Chipewyan

Peace River

SASKATCHEWAN

25

30

35

40

45

50°C

Elbow

Saskatoon

Lucky Lake

Kindersley

Stony Rapids

North Battleford

Southend Reindeer

Uranium City

Meadow Lake

Collins Bay

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE CANADA

ONE OF THE LONGEST HEAT WAVES

IN CANADIAN HISTORY

It's not just soaring temperatures that set heatwaves apart – it's also their duration. According to a study by Environment and Climate Change Canada of persistent heat at selected locations in B.C. for which a century or more of temperature data was available, heat waves lasting four days or longer are rare. This summer's heat dome event was among the longest heat waves on record – and all the more remarkable for occurring outside the traditionally hot months of July and August.

Duration (days)

Location

Date range

Kamloops

July 24 to Aug. 3, 2009

11

June 25 to July 1, 2021

7

Lytton

Aug. 8 to 17, 1981

10

June 25 to July 2, 2021

8

July 24 to 30, 2009

7

July 24 to 29, 2021

6

July 10 to 14, 2021

5

Bella Coola

July 24 to Aug. 1, 2009

9

June 24 to 30, 2021

7

July 13 to 19, 1941

7

Vernon

July 24 to 30, 1998

7

June 26 to July 1, 2021

6

July 14 to 17, 1942

4

Gonzales,

Victoria

June 29 to July 3, 1942

5

June 25 to 28, 2021

4

Vancouver

June 26 to 29, 2021

4

July 28 to 31, 2009

4

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE CANADA

ONE OF THE LONGEST HEAT WAVES IN

CANADIAN HISTORY

It's not just soaring temperatures that set heatwaves apart – it's also their duration. According to a study by Environment and Climate Change Canada of persistent heat at selected locations in B.C. for which a century or more of temperature data was available, heat waves lasting four days or longer are rare. This summer's heat dome event was among the longest heat waves on record – and all the more remarkable for occurring outside the traditionally hot months of July and August.

Duration (days)

Location

Date range

Kamloops

July 24 to Aug. 3, 2009

11

June 25 to July 1, 2021

7

Lytton

Aug. 8 to 17, 1981

10

June 25 to July 2, 2021

8

July 24 to 30, 2009

7

July 24 to 29, 2021

6

July 10 to 14, 2021

5

Bella Coola

July 24 to Aug. 1, 2009

9

June 24 to 30, 2021

7

July 13 to 19, 1941

7

Vernon

July 24 to 30, 1998

7

June 26 to July 1, 2021

6

July 14 to 17, 1942

4

Gonzales,

Victoria

June 29 to July 3, 1942

5

June 25 to 28, 2021

4

Vancouver

June 26 to 29, 2021

4

July 28 to 31, 2009

4

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE CANADA

ONE OF THE LONGEST HEAT WAVES IN CANADIAN HISTORY

It's not just soaring temperatures that set heatwaves apart – it's also their duration. According to a study by Environment and Climate Change Canada of persistent heat at selected locations in B.C. for which a century or more of temperature data was available, heat waves lasting four days or longer are rare. This summer's heat dome event was among the longest heat waves on record – and all the more remarkable for occurring outside the traditionally hot months of July and August.

Duration (days)

Location

Date range

Kamloops

July 24 to Aug. 3, 2009

11

June 25 to July 1, 2021

7

Lytton

Aug. 8 to 17, 1981

10

June 25 to July 2, 2021

8

July 24 to 30, 2009

7

July 24 to 29, 2021

6

July 10 to 14, 2021

5

Bella Coola

July 24 to Aug. 1, 2009

9

June 24 to 30, 2021

7

July 13 to 19, 1941

7

Vernon

July 24 to 30, 1998

7

June 26 to July 1, 2021

6

July 14 to 17, 1942

4

Gonzales,

Victoria

June 29 to July 3, 1942

5

June 25 to 28, 2021

4

Vancouver

June 26 to 29, 2021

4

July 28 to 31, 2009

4

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE CHANGE CANADA

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.