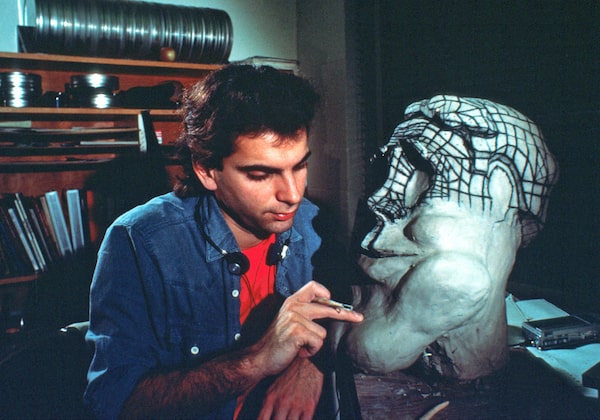

Daniel Langlois working on Tony de Peltrie (1984). The moving six-minute clip won several international awards and was a turning point, for both the budding 3-D animation industry and Mr. Langlois.Daniel Langlois Foundation

In the summer of 1985, a team of young Montreal filmmakers presented their latest creation at a San Francisco festival.

The moving six-minute clip, titled Tony de Peltrie, depicts a melancholic pianist with a disproportionate chin who becomes ecstatic as he dwells on memories and plays for an invisible audience.

“In striking contrast to the awkward, robot-like characters in earlier computer films, De Peltrie looks and acts human,” Time magazine reported at the time. “In creating De Peltrie, the Montreal team may have achieved a breakthrough: a digitized character with whom a human audience can identify.”

One of Tony’s creators, Daniel Langlois, then 28 years old, explained in an interview for Radio-Canada’s Le Point that he sculpted a model of the musician with clay, drew lines on it, digitized co-ordinates to build a database, and animated the character from there.

“The whole technique of character animation, of a synthetic character, that’s what’s new,” he explained to the host. “Subtle expressions, which can transmit feelings, express things, and above all that it’s an entire movie, that’s what’s new.”

The short film won several international awards and was a turning point, for both the budding 3-D animation industry and Mr. Langlois.

The Le Point host questioned him and a co-creator, Philippe Bergeron, about future projects: Were they going to Hollywood? Would Hollywood come to them, to Montreal?

“We’re seriously thinking about it,” said Mr. Langlois, who at the time was employed by the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) and worked on Tony de Peltrie as a side project. Mr. Bergeron added: “All that’s missing is investors.”

Over the next few years, Mr. Langlois would find investors and build Softimage, a company that produced 3-D animation software used in major films such as Jurassic Park, Titanic, Lord of the Rings and the Harry Potter series, along with numerous video games. He sold the company to Microsoft in 1994 for US$130-million.

Mr. Langlois stayed on as president and chief technology officer of Softimage until 1998 and, during the following decades, established himself as a patron for the arts and embarked on hospitality and development projects in Dominica, a small Caribbean island.

The 66-year-old entrepreneur and philanthropist was found dead with his partner, Dominique Marchand, on Dec. 1 in a burned-out car near a luxury resort they owned in Dominica. Four people were arrested and two of them have been charged with murder by Dominican authorities.

Daniel Langlois, 66, and Dominique Marchand, 58, in an undated handout image provided by the Daniel Langlois Foundation. The director of public prosecutions in the Caribbean nation of Dominica has confirmed that two American men were charged in their killings.HO/The Canadian Press

Mr. Langlois, who had no children, leaves his mother; three brothers, Marcel, Ghislain and Normand Langlois; and extended family.

Loudon Owen, an early investor in Softimage, met Mr. Langlois in Toronto, in 1986 or 1987, through a common acquaintance. “After about five minutes, we were captivated by his passion, his energy, everything about him,” he said.

Mr. Owen and two partners, John McBride and John Eckert, had been meeting entrepreneurs every day for months, looking for “interesting investments,” and Mr. Langlois stood out. “It was no contest. He was clearly a truly extraordinary young man” with a clear, bold vision of making 3-D animation accessible for everybody, Mr. Owen recalled.

Mr. Langlois also impressed the trio of investors with Tony de Peltrie. “It’s what got us absolutely convinced that this was the future, and he was the person to make that future,” Mr. Owen said.

Daniel Langlois was born in Jonquière, Que., on April 6, 1957. He studied design at the University of Quebec at Montreal (UQAM) and started experimenting with computers there, creating a sequence “of very simple forms and movements” with a “rudimentary” system, he told ASIFA Magazine, an international animation journal, in 1986.

He and fellow UQAM student Marc Aubry then went to the NFB with animated film project ideas, and they were hired.

“Marc and I did a few animation sequences but quickly hit the limits of the system,” Mr. Langlois told ASIFA. So, he read the program’s thousands of pages to understand and eventually, modify and expand it to go from 2-D to 3-D animation.

This and additional investments in equipment by the NFB led Mr. Langlois to work on the short film Transitions, the first stereoscopic 3-D computer animation in IMAX format, presented at the Expo 86 World Fair in Vancouver.

Then-director of the NFB’s French animation studio, Robert Forget, Mr. Langlois’s former boss, has mixed memories from that time. “I was expecting something a little better than what he achieved” for the IMAX film animation, he said in an interview, suggesting Mr. Langlois might have been more absorbed by his work on Tony de Peltrie and his business plans. “It was clear that he was a young man who had other ideas,” Mr. Forget said.

In a La Presse interview published in 1994, after the Microsoft deal, Mr. Langlois said: “What I want is to change the lives of several generations, all over the world.” And he did.

Softimage’s affordable, user-friendly 3-D animation software “has led to meteoric development in the cinema industry,” said Marco de Blois, programmer-curator at the Cinémathèque québécoise, which documents and safeguards Quebec’s cinema and TV heritage.

“We no longer needed to make rubber beasts, everything was animated, created virtually, brought to an absolutely extraordinary level of realism,” Mr. De Blois said, in reference to Jurassic Park’s use of Softimage’s tools in 1993.

“Suddenly, what seemed impossible became possible,” he said.

Mr. Langlois had envisioned this early: “We will soon see synthetic characters in American feature films who will replace the monsters and robots of science fiction films,” he told ASIFA Magazine in the 1986 interview.

In 1997, Mr. Langlois started a namesake charitable foundation to support artistic, scientific and technological research. The Daniel Langlois Foundation led projects such as Digital Snow, an interactive catalogue of the work of Toronto-born artist Michael Snow, whom Mr. Langlois admired, and the DOCAM Research Alliance, dedicated to developing methods to preserve the media arts heritage.

Mr. Langlois also founded the performing arts centre and cinema Ex-Centris in Montreal, as well as 357c, an exclusive private club where a who’s who of business, culture and technology figures in Quebec used to rub shoulders. Both institutions no longer exist.

In 1997, Mr. Langlois was part of a team that received a Scientific and Technical Oscar from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences “for the development of the ‘Actor’ animation component of the Softimage computer animation system.”

In 1999, he was appointed Knight of the National Order of Quebec and, in 2000, he was invested as an officer of the Order of Canada. Mr. Langlois received Honorary Doctorates from Sherbrooke University, McGill University, Concordia University, the University of Ottawa and UQAM in recognition of his work in the fields of art, science and technology.

In 1997, Mr. Langlois started a namesake charitable foundation to support artistic, scientific and technological research.HO/The Canadian Press

More recently, Mr. Langlois and his partner, Ms. Marchand, opened Coulibri Ridge, an off-grid luxury eco-hotel set atop a mountain ridge in southern Dominica that the couple spent two decades researching, designing and building.

Mr. Langlois’s foundation also created the Resilient Dominica (REZDM) Project, an environmental-resilience program that sought to help with the response to damage caused to the island by Hurricane Maria in 2017. One of its projects was to help rebuild an elementary school that was battered by the storm, allowing students to return in 2019. In recent months, the organization has been working on coral reef restoration.

Simon Walsh, a project manager for REZDM, met Mr. Langlois in the late 90s when he and his partner were visiting Dominica, where Mr. Walsh was operating a dive shop. They stayed in touch and, when Hurricane Maria destroyed Mr. Walsh’s home and business, along with much of the island, Mr. Langlois came up with the idea of REZDM.

He offered Mr. Walsh the job and a place to stay until he could rebuild his home. “He saved me,” Mr. Walsh said, and had a great, positive impact on the community.

In an open letter published in Le Devoir, Jean Gagnon, who was director of the Daniel Langlois Foundation between 1998 and 2008, tried to summarize the man’s legacy. There is an important art collection left under the care of the Cinémathèque québécoise, he wrote.

But above all, “there remains the example of a conviction, perhaps idealistic, of the ability of artists to intervene in the major issues of our world, whether technological, environmental or social.”