After three decades as an emergency physician at Edmonton’s Royal Alexandra Hospital, Louis Hugo Francescutti has come to realize that medicine alone is not health care.

For years now, he has watched an alarming spike in the number of homeless patients coming through his ER’s doors. Just as troubling, he says, is that of the nearly 9,000 patients with no fixed address who visited Edmonton emergency rooms last year, many of them wound up sent back to the same illness-inducing circumstances that landed them in the ER in the first place – only to see them return again, sicker.

To break that cycle, last winter, Dr. Francescutti and his colleagues launched a local pilot program that provides transitional housing for patients that would otherwise be discharged from hospital into homelessness. The Bridge Healing Transition Accommodation Program, considered the first of its kind in Canada, provides 36 recovery rooms spread across three buildings in the city’s west end. In the program’s first year, more than 100 people checked into Bridge Healing, staying an average of 45 days each. Many of them have gone onto permanent housing, Dr. Francescutti said.

But even as his team celebrates that success, he acknowledges that it barely begins to address what has become a public health epidemic faced by physicians at hospitals across the country.

Last year, at only two Toronto emergency rooms – in Toronto Western Hospital and the Toronto General Hospital, both of which are part of the University Health Network (UHN) – the 100 most frequent ER users recorded as having no fixed address made a collective 4,309 visits.

In total, this tiny group – representing 0.12 per cent of all UHN patients – accounted for 3.5 per cent of the year’s ER visits. Twenty-four of these patients made more than 50 visits each, and some came more than 100 times.

For years, these patients have been pejoratively labelled “frequent flyers” – accused of tying up the health care system with unnecessary and gratuitous visits. But as homelessness rates increase across the country – exacerbated by a mental health and addictions crisis – ERs have become almost an inevitable destination for Canada’s most vulnerable.

Fearing where things are headed, a chorus of doctors are calling for radical change: making the case, to whomever will hear them, that safe, affordable, secure housing is the best prescription for their patients.

Alternative community health care supports have long existed at the grassroots level. But now, physicians and hospitals are also beginning to look for ways to address the root social causes of their patients’ illnesses and injuries. Some are setting up satellite services outside of the health care facilities to provide care near shelters, parks and tent encampments. Others are going so far as to provide housing itself.

In short, physicians are reckoning with what UHN physician Andrew Boozary calls “the heart and soul” of medicine, in a country that prides itself on universal health care. “We can’t really talk about universal health care without housing as a human right.”

Solutions in motion: University Health Network, Toronto

Toronto has long treated housing and health care as separate social problems, but the city’s largest hospital network hopes that an integrated approach will be better for unhoused people – and for overstretched emergency rooms.

Later this year, UHN expects to open a housing complex for homeless and at-risk patients. And since 2022, it has had a special clinic for people who may have overdosed, but are stable enough to skip the ER. That means paramedics can leave within minutes, as opposed to the hours they might wait at a hospital.

Photography by Melissa Tait

Within hospitals, there is a code used to track the prevalence of homelessness among patients, under the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

And while the code – Z59.0 – is mandatory for Canadian hospitals to use, its reliability for statistical purposes varies province to province, and even hospital to hospital. Doctors and nurses are not obligated to ask patients about their housing status, so this information is not always making it onto medical charts in the first place – meaning the picture is incomplete.

This is especially true in the emergency department, where discussions tend to be brief and to the point. Those who come in with what are deemed non-urgent issues, looking for temporary refuge, may not even speak with a doctor.

But missing these people in the data leaves a crucial gap in our understanding of the breadth of this crisis – and impedes a fulsome response.

Tracking the rise of homelessness in Canada, even generally, is a challenge. The term “homelessness” is broad, encompassing everyone from the chronically unhoused and living in tents or on the street, to those staying in a shelter, or couch surfing with family or friends.

As of 2021, Statistics Canada – citing a 2014 study by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness at York University – estimated that an average of 235,000 people in Canada experience homelessness each year.

As tent encampments like this one in Halifax become increasingly common, data gaps leave a crucial gap in our understanding of the breadth of this national crisis.Darren Calabrese/The Canadian Press

Otherwise, homelessness is currently estimated at a national level through “point-in-time” counts, which provide a one-day snapshot in 72 communities across Canada. The most recent count, taken in each city on a single day between 2020 and 2022, found that homelessness as a whole is on the rise – increasing by 20 per cent since the 2018 count. Chronic homelessness (defined as lasting for six or more months) increased by 60 per cent. Alarmingly, the largest increase – a staggering 88 per cent – was among the truly unsheltered: those sleeping outside in tents or in doorways or abandoned buildings.

These concerning trends prompted Canada’s Federal Housing Advocate to release a report on encampments in February, which called on the federal government to establish a formal national encampments response plan by the end of the summer.

For the first time, the count also gathered data about the health challenges faced by those experiencing homelessness. The vast majority of those surveyed (85 per cent) reported having at least one health challenge, and 67 per cent reported having more than one.

Homelessness, in and of itself, is a major health concern, causing or compounding an endless list of physical and mental illnesses. Hypothermia and frostbite. Burns or chemical inhalations from lighting fires to keep warm. Viruses spread through overcrowded congregate settings. Foot infections worsened by wet socks, ill-fitting shoes or lack of access to clean water to wash and dress wounds. Chronic pain. Depression, anxiety and psychosis.

Those experiencing homelessness are also disproportionately likely to struggle with drug use and addictions, which in a toxic drug supply crisis too often leads to serious health issues, or death.

At Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital, roughly 20 per cent of the patients Carolyn Snider sees in the ER are homeless. And she stresses that even 20 per cent is likely an undercount. Dr. Snider, an emergency physician and scientist with the hospital’s MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, co-authored recent studies on the rise of weather-related injuries caused by homelessness, as well as the increase in “non-urgent” ER visits by patients experiencing homelessness during the winter months in Ontario. The research identified a province-wide spike in these visits of 24 per cent in 2022/23. In Toronto alone, they rose by 68 per cent.

Carolyn Snider, until recently the emergency-department chief at St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto, co-authored a study that found a surge in 'non-urgent' hospital visits by unhoused people in Ontario.Laura Proctor/The Globe and Mail

The study found that many of the people came into the ER to connect with a social worker to get help finding shelter, Dr. Snider said in a phone interview in February.

“But as one of our outreach workers yesterday said, she hasn’t been able to get anyone connected into a shelter since late October, early November.”

As a result, Dr. Snider – who recently completed her tenure as chief of emergency medicine at the hospital – said they routinely have to tell people who are unhoused that there are no beds available. No chairs for them, even, sometimes. That the hospital simply won’t be able to help them. She knows this means they will likely wind up back in the same circumstances that brought them there, trapped in an escalating cycle of poor health.

“And it’s an awful, awful feeling,” she said.

A bloody mask, socks, drug paraphrenalia and a Christian booklet lay in the snow outside the Royal Alexandra Hospital. In cold weather, homeless people might have nowhere to turn but a hospital.Amber Bracken/The Globe and Mail

Particularly in the harshest winter months – when homeless shelters and warming centres are full, when public bathrooms are locked, and when people are shuffled out of coffee shops and malls – ERs become the last refuge for a growing number of people who are simply desperate to keep warm or dry.

Stephen Hwang, director of the MAP Centre, stresses that just because a patient’s visit is technically classified as non-urgent, does not mean that their presence in hospital is unnecessary.

“Frankly, coming there because you’re really cold and there’s no place for you to go actually makes perfect sense,” he said.

“If you were on the street and you were freezing, and everything was closed, and the only place you could go was into the emergency department, we would all march into the emergency department and say, ‘I need to warm up.’ And it’s so it really is not unnecessary, it’s just unfortunate.”

Solutions in motion: Rotary Club of Toronto Transition Centre, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto

Since 1999, this Toronto hospital has had a temporary resting space for people who are discharged from the emergency department but have nowhere else to go. A community support worker is on duty 24/7, and a sleep room – which doubles as an office during the day – lets patients stay the night or wait to see a social or outreach worker. Clothes, toiletries, food and showers are also available at the Rotary Centre.

Photography by Laura Proctor

On an evening in February, Dr. Francescutti had a homeless patient come in with major swelling in his leg. The man’s other leg had already been amputated due to a severe burn, and his remaining leg was “weeping,” with fluid leaking out of a wound.

“How in hell is he supposed to take care of that when he’s got mobility issues? He’s got pain, it’s infected, he’s about to go septic,” Dr. Francescutti said. “And so that’s the kind of patient that – why are we surprised that he keeps coming back to emergency?”

Scenes like this, playing out daily in ERs across the country, are the consequence of what experts say boils down to an absence of adequate affordable housing and social supports.

Tim Richter, executive director of the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness, said that without those things – and in a very expensive real estate and rental market – people who can’t compete are being forced out the bottom.

“They tend to be people that have already had some trauma in their lives, or come from child welfare, or some other public system. They’re struggling with addiction. They’re struggling with health issues. They have a disability, a brain injury, a developmental disability,” Mr. Richter said, adding that many of the same people who wind up in hospital again and again may similarly end up in and out of jail.

A Globe and Mail analysis last fall found that one in five inmates released from Ontario jails are discharged into homelessness – a similarly futile cycle that only fuels the crisis.

“So we end up allowing people to cycle aimlessly between all of these very expensive public systems, because we don’t address their housing need,” Mr. Richter said. “They then become the problem of health care or corrections or whatever.”

A paramedic disinfects equipment after an ER drop-off at St. Michael's Hospital, where staff often find themselves dealing with the fallout of a housing crisis.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

For the doctors that treat these patients, the moral injury or psychological distress from the system’s failings is taking a toll.

At St. Michael’s Hospital in downtown Toronto, Sahil Gupta said the futility of these encounters can breed desensitization. The patients are often frustrated, he said. They haven’t slept. They’re on edge. “And then we say we’re one more person that can’t help – ‘Here’s a pamphlet of resources,’ and so on. You know, that’s really injurious both for us … and it leads to aggressions and challenges sometimes that creates further desensitization, and it becomes this downward spiral in some ways.”

Doctors are not the only frontline health care workers feeling the toll of the housing crisis.

As an in-patient social worker at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, a primary part of Sarah Morgan’s role is to help patients to transition out of the hospital once they are stabilized.

But more often than not, she said her patients – who have complex and often layered needs – are coming in homeless. And supportive housing options are virtually non-existent.

“People don’t have anywhere to go. And we know just through the social determinants of health, one of the biggest keys to success is people having somewhere safe for them to recover,” she said.

“How as health care providers are we to expect our patients to show up to appointments, to take their medications, to stay out of hospital and essentially to fend for themselves, if we’re not able to provide those basic human needs? It’s unreasonable.”

At CAMH in Toronto, social worker Sarah Morgan says her patients often end up staying months or years, because they have nowhere else to go.Cole Burston/The Canadian Press

It pains her to sit across from a patient or their family, and tell them that the supports they need simply don’t exist. That they are just stuck in the hospital – sometimes for months or years. “You’re the face of a system that is broken,” she said.

When they do find somebody housing, she said the transformation is magical. But even in those cases – which she said are the exception, not the rule – there is a lineup of people behind them waiting for that spot in the hospital.

“There’s this constant turnover when somebody’s being discharged, we already have a name for who’s coming next. It’s just a constant flow,” she said.

In Dr. Francescutti’s view, the current system is an unconscionable failing. He questions why it is legal to discharge patients into nothing, even challenging Accreditation Canada – which sets national standards for hospital performance – to bar health care facilities from doing so.

“Treating them and streeting them – putting them back on the street – doesn’t help anyone,” he said.

“If there was any other patient that we ever thought we’d be sending home at increased risk of death, we’d be concerned. But for homeless patients, we don’t – and the reason is we’ve become habituated.”

Solutions in motion: Cool Aid Mobile Inner-City Outreach unit, Victoria

When COVID-19 arrived in 2020, it put health care even further out of reach for Victoria’s most vulnerable people – so a non-profit decided to bring health care to them, first to motels and hotels and later to tent encampments. CAMICO’s team treated injuries, managed prescriptions and took people to vital appointments. Today, they continues this work with roughly 20 doctors and 17 nurses.

Photography by Chad Hipolito

Discussions around whether people should be offered supportive housing in order to keep them out of the ERs, and out of the health care system in general, often revolve around a goal of cutting costs. But experts argue we should be looking instead at how to spend in a less wasteful way – and in a way that’s more compassionate.

At Home/Chez Soi, a years-long study of homelessness and mental illness led by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, found that “housing first” – an approach that focuses on moving homeless people into permanent housing and then providing additional supports and services as needed – is proven to keep people housed long-term.

And though they found that this approach does not necessarily lead to overwhelming cost savings in the short or medium term, it does lead to a more appropriate allocation of funds.

Instead of pointlessly shuffling people between shelters and jails and hospitals, housing people can help to stabilize them and connect them with the ongoing supports they need.

“We need multifactorial, multipronged efforts in terms of prevention of homelessness,” said Eric Latimer, a McGill University psychiatry professor and the study’s main author. “Maybe we’ll spend somewhat more money, but it will be to deliver a much smarter set of services for people, and people will be much better off as a result.”

A Montreal housing project inaugurates new units for homeless people. Researcher Eric Latimer says 'housing first' policies can yield important benefits down the road.Christinne Muschi/The Canadian Press

For the most part, the study found that in-patient and emergency service use fell, particularly among higher-needs participants. But he also gave the example of one participant who actually wound up “costing” more money after he became housed, but only because through a support worker it came to light that he had Hepatitis C, and he was admitted to hospital for two cycles of treatment.

Had he not entered the program, it would’ve been cheaper, but he likely would be no longer alive. “The Hepatitis C would have eventually destroyed his liver and he would have died,” Dr. Latimer said.

In the long term, he says the Housing First model very likely has the potential for savings – though there is a lack of research tracking anyone long enough to know for sure. (The At Home/Chez Soi study, for example, only followed people for two years.)

Either way, he said the approach must not be looked at as something simply meant to save money, but as something meant to save lives.

“It’s more humane,” he said simply. “What kind of society do we want to live in?”

As the Bridge Healing program in Edmonton reached its one-year anniversary, the province’s Premier has been vocal in her support, and Alberta Health Services has fast-tracked funding.

The program is also rapidly expanding, having already secured five more lots and eyeing six more – each of which will house an additional 12-unit modular building by the end of this year.

“So we are aiming at another 132 this year and probably the same next year – till we have the capacity to meet the needs of every homeless patient that wants a fresh start in life,” Dr. Francescutti said in an e-mail.

Marion Selfridge is the research manager with the Cool Aid Society’s community health centre in Victoria.Chad Hipolito/The Globe and Mail

In Victoria, the non-profit Cool Aid Society has provided housing, health care and social supports for people experiencing homelessness and poverty since the 1970s; today, this includes both health and dental clinics as well as emergency shelters and transitional and supportive housing across 20 locations in the city.

As the backlog for housing grows in the province, those who work at the Cool Aid Society say the idea of “transitional” housing is becoming unrealistic. Even at their emergency shelters, they have long since abandoned their 30-day stay limitations, as people can now end up staying years.

“It’s not possible just to check people out,” said Marion Selfridge, research manager with the organization’s community health centre.

They have similarly adapted their health care approach from an exclusively bricks-and-mortar model to one that meets people where they are at. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, as social services shut down across the country, the organization established the Cool Aid Mobile Inner-City Outreach (CAMICO) team, to bring health care to people at temporary shelter sites set up at hotels and motels in the city.

Between May and September 2020, they provided more than 9,823 visits to 414 clients, many of whom have substance use disorders or chronic mental illness.

The health benefits for the patients were obvious. Doctors were identifying issues much earlier, and helping people with wound care and prescriptions, and even transportation to appointments that might have otherwise been missed.

But in an evaluation of that program, Ms. Selfridge said they also discovered a broader system benefit: ER visits by these patients were way down.

Today, the organization’s health program – which now also visits designated encampment sites in the city – has roughly 20 doctors and 17 nurses on their team, and in the last year facilitated about 60,000 patient visits. Over the last three years, they’ve seen roughly 7,300 individual patients.

But without a radical increase in affordable housing, Ms. Selfridge said their efforts only go so far to break the cycle.

“You can do as much primary care as you want. But if you don’t have places for people to go that work for them, it’s such a struggle,” she said.

UHN's Dr. Andrew Boozary rejects the notion that physicians who advocate for housing policy are stepping out of their lane. 'The reality is that is very firmly in our lane, because the only other options for people are to come back to the hospital or try to seek other health care supports.'Melissa Tait/The Globe and Mail

Back in Toronto, Dr. Boozary and his UHN colleagues are also looking outside the traditional structures of medicine for innovative solutions.

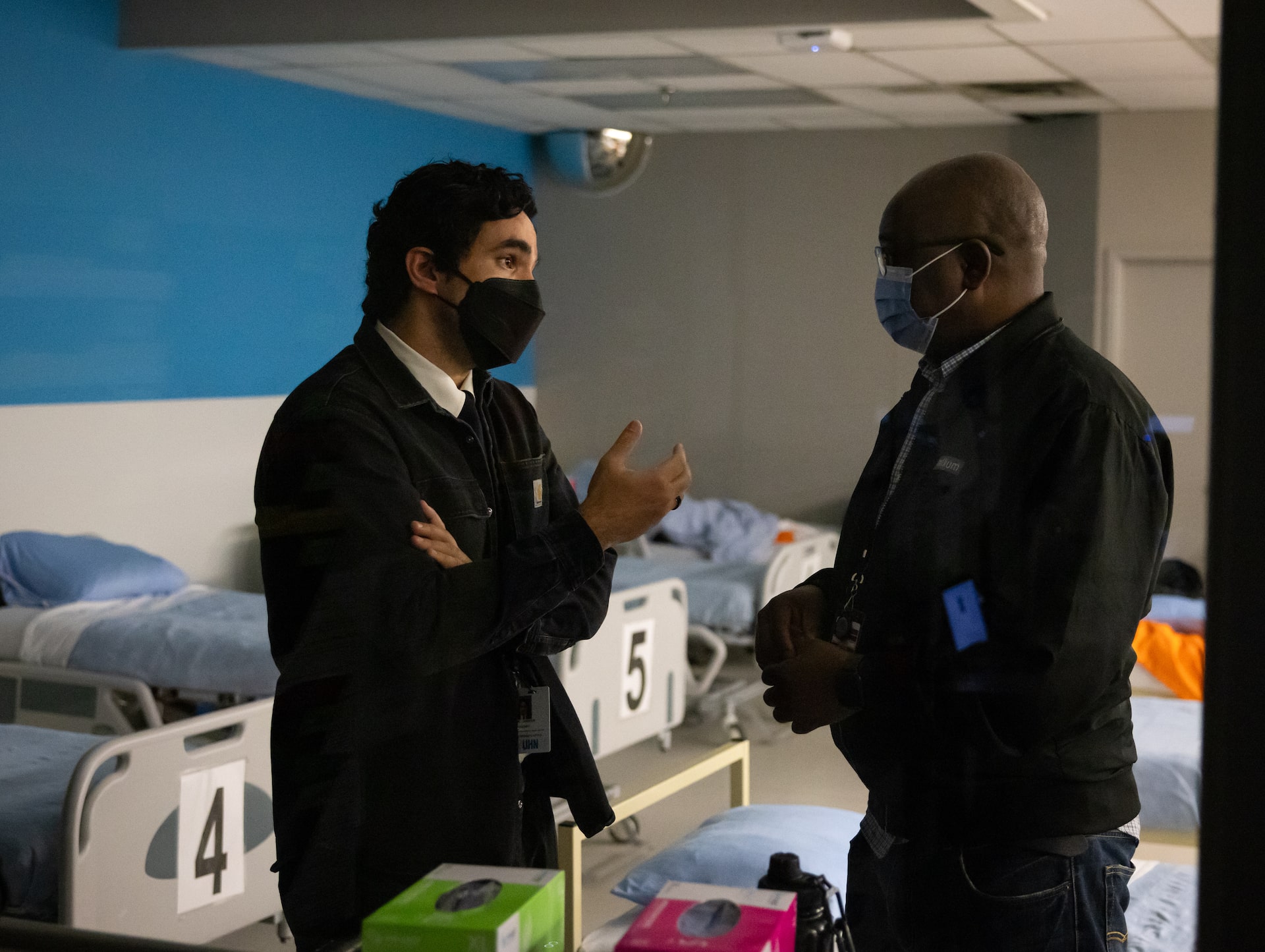

Dr. Boozary leads a new stabilization clinic, opened in December, 2022, where paramedics can bring intoxicated people – most of whom are homeless – to sober up. In addition to an on-call doctor, the clinic is staffed by peer support workers with lived experience who can help connect patients with social services when they are ready.

The program is win-win: they provide people with more relevant care, and are able to drastically cut ambulance offload times and free up ER beds.

And construction on an even more ambitious project is underway: a four-story modular apartment building is expected to open this summer, providing 51 units to permanently house patients within the UHN system who are, or are at risk of becoming, homeless – with a focus on seniors, women, and Indigenous and racialized people.

In the most recent point-in-time count, 31 per cent of people experiencing homelessness identified as Indigenous – a stark overrepresentation, considering census data shows only 5 per cent of people in Canada identify as Indigenous.

The housing project represents a meshing of worlds – health and housing – that have traditionally been treated as separate in Canada, funded and handled by different government ministries.

Indeed, for a long time, physicians who advocated for housing and social justice were told to stay in their lane.

“The reality is that is very firmly in our lane, because the only other options for people are to come back to the hospital or try to seek other health care supports,” Dr. Boozary said.

In Dr. Boozary’s view, the health care system requires a complete rethink, rather than simply “tinkering around the margins.”

“I really feel that we are at this real battle for both the heart and soul of medicine, around where this discipline needs to be able to move.”

For Dr. Hwang – one of the world’s leading researchers on homelessness, housing and health – it’s bittersweet, after decades of sounding the alarm, to finally see these problems tackled as one interconnected issue.

“What was once kind of a fringe, unusual kind of position to take has now become much more common, and actually much more, I guess, recognized as common sense,” Dr. Hwang said. “So I think things have changed, but you know, we’ve still got a long way to go.”

Data analysis and graphics by Yang Sun

Housing and homelessness: More from The Globe and Mail

City Space podcast

Halifax’s homeless population has tripled in the past three years. How did that happen? And in the absence of new housing, policies and money, is leaving people to camp in parks really the best a city can do? Irene Galea explores those questions on the City Space podcast.

Commentary

André Picard: Paying more attention to the health and social benefits of libraries is overdue

Gregor Craigie: Can other countries offer practical solutions to Canada’s housing crisis?

Gary Mason: Canada’s housing crisis is leaving many seniors out in the cold - literally