Dr. David Bailey, shown holding a grapefruit in 2017, was a Canadian Olympic runner and a pharmacologist who made the game-changing discovery that consuming grapefruit juice has an effect on how the body reacts to various medications. He died of an apparent heart attack on Aug. 27, at age 77.Courtesy of Lawson Health Research Institute

David Bailey improved countless lives because of a discovery he made by accident.

In the late 1980s, Dr. Bailey, an Olympic runner-turned-pharmacologist, was researching the effects of alcohol on the blood-pressure medication felodipine. Seeking to disguise the alcohol’s taste in his experiment, he tried combining it with grapefruit juice and stumbled upon the fact that his subjects’ consumption of the juice resulted in a greater concentration of the drug in their bloodstreams. He went on to discover that grapefruit juice has this effect because it inhibits an enzyme (CYP3A4) in the human gut that breaks down the medication, so the body consequently absorbs a larger than normal amount of the medication.

“People didn’t believe us,” Dr. Bailey told The New York Times. “They thought it was a joke.”

In 1991, Dr. Bailey’s findings were published in the prestigious international medical journal The Lancet and reported by several other academic publications and media outlets. The phenomenon he identified came to be known as the grapefruit effect.

Over the years, Dr. Bailey’s follow-up research determined that grapefruit juice has harmful interactions with some 100 oral medications, with the potential either to cause an overdose or, in some cases, to do the opposite and reduce the drug’s benefit.

As a result, many prescription medicines now carry labels warning patients not to consume grapefruit juice with them.

“His discoveries have improved the quality of life for millions of patients using [prescription] drugs,” said George Dresser, a former PhD student and colleague of Dr. Bailey at what is now known as Western University, where Dr. Bailey worked for more than three decades.

Bailey competes in the 1,500-metre event at the Pan Am Games in Winnipeg in August, 1967.Courtesy of Scott Bailey

Affected medications include those designed to treat AIDS, heart disease, cancer, celiac disease and many other maladies, as well as those to prevent organ-transplant rejection.

Dr. Dresser said “it’s quite likely” that some patients who took medication with grapefruit juice died before Dr. Bailey made his initial discovery.

“One of the most challenging aspects of giving a patient medication for a chronic condition,” Dr. Dresser said, “is that sometimes the drugs work and sometimes the drugs don’t work.

“That variability … creates a lot of misery for people. His discovery was that what you take with your medication makes a huge difference. And, the information that was provided made it easier for patients and made it easier for doctors to be able to make sure that the drugs did what they were supposed to.”

The severity of the overdose effect varies widely by patient, Dr. Dresser said, but on average, the amount of the drug in the bloodstream increases threefold. In some cases, as with blood-pressure medication, he noted, the increased potency could cause a severe headache and leave the patient feeling flushed.

After experiencing this side effect and not understanding its cause, patients would often refuse to take their medication – even though it would have worked properly when taken with water.

(Dr. Bailey reported experiencing a severe headache after he tested the grapefruit juice-felodipine mixture on himself before expanding his research. “Once I took the drug with water, then I took it with grapefruit juice,” he told an interviewer for a story published in the London Health Science Centre’s website. “My drug levels were five times higher with grapefruit juice. That was a big Eureka moment.”)

In other cases, as with statin drugs used to reduce cholesterol, a grapefruit juice-medication mixture could cause “major problems,” Dr. Dresser said.

“Many of the statin medications that we were using in the 1990s and early 2000s would have a very significant increase in the blood level,” Dr. Dresser said. “And, those increases in the blood level were associated with significant muscle pains and, in some cases, muscle destruction [and] kidney failure as a result of having too much of the drug in your bloodstream. That would be one [example] where, I suspect, there probably were deaths before David’s discovery came along and allowed us to figure out that [grapefruit juice] was something that we needed to warn our patients about.”

Before starring in the lab, Dr. Bailey, who died of an apparent heart attack on Aug. 27 at age 77 in his London, Ont., home, made history on the track.

He became the first Canadian to run a mile in under four minutes, and represented Canada in the event, which is rarely staged any more, at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City – after overcoming considerable adversity as a youngster.

David George Bailey was born March 17, 1945, in Toronto. He was the adopted oldest child of George and Barbara Bailey (née Smith), who also had a daughter, Joan. His father worked in sales and his mother was a homemaker.

David’s birth father was a Canadian aviator who had a romance with the boy’s birth mother during the Second World War. Dr. Bailey only learned of his biological parents’ identities in the past year. He conducted online genealogical research, utilized a DNA-matching service and convinced provincial officials that knowing the couple’s names could benefit his health, although he had no specific medical problem, his son Scott said.

Gladys Boyd, a pediatrician who had pioneered insulin treatment for diabetic children, was a first cousin of Ms. Bailey and assisted her and her husband in adopting David. Dr. Boyd also sparked his interest in science.

Owing to a change in Mr. Bailey’s work, the family relocated to Michigan, where David played many sports and developed a love of running.

“He had a natural aptitude for it,” Scott Bailey said. “As a kid, he liked running around dealing with the bullies. He’d tease them and then take off because he knew he could outrun ‘em.”

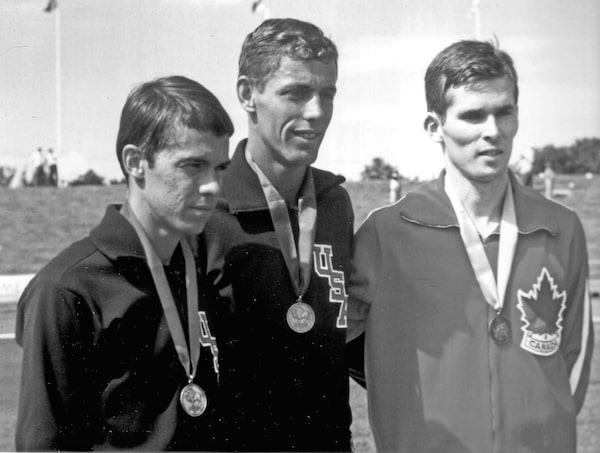

Bailey, right, and other medalists in the 1,500-metre run at the Winnipeg Pan Am Games.Courtesy of Scott Bailey

When David was nine years old, tragedy struck. He lost an eye in an accident involving a knife while building a tree fort with other neighbourhood kids.

A glass eye was inserted and he was prohibited from playing contact sports to avoid the risk of another injury and complete blindness. When David was 11, his father died of a heart attack and the reduced family returned to Toronto.

David struggled through his early teens and lacked a sense of identity as a result of the eye injury and exclusion from contact sports, according to Harvey Mitro, a runner, writer and long-time friend. But a high-school coach recognized David’s running talent and, in 1961, placed him in the East York Track Club.

The club was led by legendary coach Fred Foot, who later mentored him at the University of Toronto and also worked in the Canadian Olympic program. David flourished under Mr. Foot’s guidance and the opportunity to train, and compete occasionally, with two older athletes: Bruce Kidd and Bill Crothers, who specialized in other distances and would become running legends.

While the three runners trained together, Mr. Kidd, won the 1962 Commonwealth Games six-mile event and competed in the 1964 Olympics. Mr. Crothers, a two-time Olympian during those years, earned an 800-metre silver medal at the 1964 Tokyo Games.

In 1962 at Varsity Stadium in Toronto, David set a world record in the mile for his age group, as a 17-year-old. And, late one Saturday night in June, 1966, in San Diego, he became the first Canadian to run a mile in under four minutes, posting a time of 3:59.1.

But Mr. Foot wanted him to break four minutes in Canada, too, Mr. Kidd recalled. So the coach organized another race, in July of 1967 at Varsity Stadium – without revealing the goal to David so that he would not feel extra pressure.

Mr. Foot instructed Bryan Emery to set a fast first-lap pace and secretly told Mr. Crothers to drop out at the three-quarter mark, according to Mr. Kidd. David was hot on Mr. Crothers’s heels when he quit running.

“I will never forget the look on [David’s] face when he realized what was happening,” Mr. Kidd said. “Bill just stepped off the track after taking the second step in this superb pace-setting job. Dave looked at him with the expression ‘Oh, my God,’ and then just put his shoulder down and just barrelled ahead to that fabulous time.”

He crossed the finish line in 3:57.7, becoming the first Canadian to break the four-minute-mile barrier in Canada.

Individually and as a team member, he garnered multiple conference and Canadian championships at the university level and berths in the U of T and Ontario sports halls of fame, among other accolades. He also captured silver medals in 1,500-metre races at the 1967 Oslo Bislett Games and 1967 World University Games (now Universiade) in Tokyo, and bronze in the mile at the 1967 Pan-Pacific Games in Winnipeg.

In addition, David ran the mile at the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Kingston, Jamaica, and the 1968 Olympics but did not medal.

Through Mr. Crothers, who was a pharmacist, he became interested in a career in pharmacy.

After obtaining an undergraduate degree in pharmacy and a master’s and PhD in pharmacology from the U of T, he did post-doctoral work at the University of Saskatchewan and joined the global drugmaker known today as AstraZeneca.

Dr. Bailey bonded with AstraZeneca’s CEO, also a runner, who planned to move him to Sweden, the company’s home base, for a few years. But a misunderstanding with local management about career intentions prompted his dismissal, Scott Bailey said.

Yet, the departure was a turning point in his career, according to his son, because AstraZeneca provided severance pay for a year, enabling him to obtain his pharmacist licence and funded the research that led to his discovery on grapefruit juice.

“The reason that he figured out the grapefruit juice thing was based on just persistence and tenacious follow-up of the data,” Dr. Dresser said. “It’s an unexpected finding that didn’t make any sense.”

Outside of work, Dr. Bailey volunteered with the London West Track and Field Club, often serving as a starter, assisted at various meets and delivered inspirational talks to various runners and high-school classes.

“He was a pretty humble guy that didn’t really talk about his own performances, but we’d always have to let people know,” said Scott MacDonald, the London club’s manager.

Dr. Bailey cut the ribbon on the inaugural Cambridge Classic Mile in 2004, hosted by non-profit running group Run for Life, on a dirt track in Cambridge, Ont. Kenya’s Laban Rotich competed in the 2005 Classic and invited Run for Life director John Carson to visit his home near Mosoriot, Kenya. In November of that year, Mr. Carson took with him about 23 kilograms (50 pounds) of pharmaceuticals purchased and donated by Dr. Bailey and assembled by the non-governmental organization Health Partners International of Mississauga, Ont.

“The drugs were very well-received and supported a rural pharmacy,” Mr. Carson said. “Painkillers, antibiotics and other drugs are expensive and not always accessible to poor, marginalized populations.”

After Dr. Bailey’s donation, other Run for Life volunteers, in subsequent years, helped to donate more than $50,000 worth of medications to this rural clinic in Kenya, according to Mr. Carson.

“He was a very genuine individual,” Mr. Crothers said.

Dr. Bailey was predeceased by his wife of 50 years, Barbara. He leaves their daughter, Karen; sons Brian and Scott; seven grandchildren; his sister, Joan Stalker; and extended family.