From the moment police arrived at the smouldering crime scene on Dec. 1, they could tell that the Nissan X-Trail had been pushed down the overgrown jungle road while still on fire. There was a terrible story written in the trail of melted plastic and blackened car parts that littered the route.

At the top of a hill, high in the volcanic mountains overlooking the fishing village of Soufrière on the southern tip of the Caribbean island nation of Dominica, scorched grass and plastic marked a likely ignition point. The culprit, or culprits, had tried to push the Nissan to the left, down a steep cliff where it would have been concealed from passersby. But the debris trail suggested the car had instead veered right, where it hung up on the road’s shoulder.

With the vehicle fully engulfed, they had somehow coaxed it back onto the road, and directed it down an embankment, where it lodged against a cluster of trees. It remained there overnight and into the next morning, in plain view of a group of villagers walking to work around dawn. They alerted police, who found the incinerated remains of two people inside.

Charred vegetation and debris remain at the site where the car was found in the hills above Soufriere.

The victims were later identified as Daniel Langlois and Dominique Marchand, a pair of wealthy Canadians who were beloved throughout Dominica for having invested heavily in an array of local projects. They were burned beyond recognition.

As Joeffrey James, Dominica’s Assistant Superintendent of Police, considered the crime scene that morning, he concluded that the person, or people, responsible for such a clumsy operation would have been seriously burned. He also noticed signs that an accelerant had been used to set fire to valuable forensic evidence, which he said was an indication that this wasn’t a local job.

“To me, it looked to be a crime of passion, of deep-seated hatred,” Mr. James said at police headquarters, from behind a desk littered with manila case files, a copy of Barack Obama’s presidential memoir and a Bible open to the Book of Psalms.

“It was a highly unusual scene in such a peaceful country. And it has saddened the entire nation to see people so respected meet their demise this way.”

Later on the same day the wreck was discovered, Dominican police arrested three people, including Jonathan Lehrer, an American landowner and cocoa farmer who was much less beloved by locals, and who had been involved in a bizarre, multiyear property dispute with Mr. Langlois over a stretch of island roadway. Their battle had spilled over into the island’s courts, and a final ruling was imminent.

The deaths and arrest shocked this country of 72,000 people, a mountainous island roughly the size of Calgary. Even in the bustling capital of Roseau, everyone greets one another on the streets, native and newcomer alike.

It’s a place where secrets aren’t kept for long, especially when they tell a story about monied foreigners and a government-sanctioned investment scheme for doomsday preppers.

Daniel Langlois and Dominique Marchand were captivated by Dominica and built businesses in Soufriere with Mr. Langlois's wealth from a 3-D animation company.Daniel Langlois Foundation via CP

Mr. Langlois and Ms. Marchand first laid eyes on Soufrière in 1997. Three years earlier, Mr. Langlois had sold Softimage, his pioneering 3D animation company, renowned for work on movies such as Jurassic Park and Titanic, to Microsoft for US$130-million. He remained heavily involved with the company, but was looking for a change of scenery and life direction.

He was consumed with the idea of building a self-sustaining luxury resort in a tropical locale. It would be built with local materials, powered by wind and solar energy, and fed by rainwater. He referred to it as a research project, not a resort – one that would prove that opulence could exist without environmental compromise.

Mr. Langlois had scouted other locations, but the couple felt as though they would be remiss if they skipped the island with which Ms. Marchand shared a name.

Soufrière, at the south end of Dominica, soon laid a spell on them, as it does many visitors. They dived among coral reefs with a charming divemaster named Simon Walsh, paddled among turtle nesting grounds and hiked to Petit Coulibri, an untouched ridge of land facing south toward Martinique.

Dominica felt removed from the tourism hustle and bustle of surrounding islands, and the villagers were among the friendliest people they’d encountered anywhere. Mr. Langlois bought 285 acres on the majestic ridge they had hiked.

“The land started to talk to me and tell me what it should be,” he would later say in a promotional video.

The Canadians' resort was built to operate with water from rain and energy from the wind and sun.Supplied by Coulibri Bridge

The whole project had the far-out feeling of Isla Nublar, the fictional island in Jurassic Park. Petit Coulibri was only 3.3 kilometres from Soufrière, but the steep access road leading to it seemed like a passage to another world. It wound through thick rainforest, past the ruins of a defunct colonial plantation called Bois Cotlette and out onto sun-kissed volcanic cliffs.

Mr. Langlois brought to the construction process the same exacting eye that had served him well animating dinosaurs and doomed ocean-liners. He studied the way the light struck Petit Coulibri at all hours of the day to calculate optimum solar-panel angles. He designed buildings, water schematics and electrical systems, drawing on his computer engineering skills.

While his dream came together, he quietly sponsored countless community businesses and activities, including Caribana festivities.

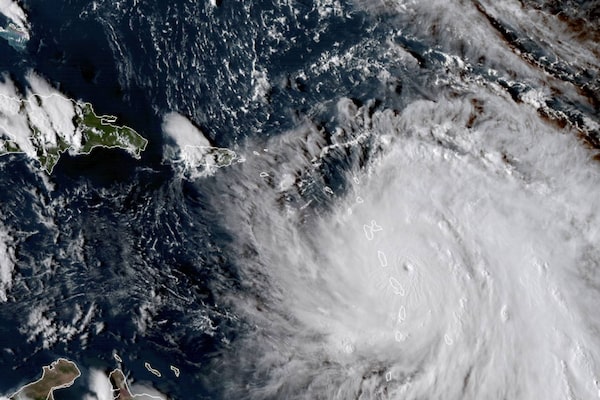

The eye of Hurricane Maria approaches Dominica on Sept. 17, 2017, before its landfall the next day.NASA

On Sept. 18, 2017, the event that would forever endear Mr. Langlois to locals came sweeping in from the southeast. Hurricane Maria stripped the roofs off 90 per cent of the island’s homes, knocked out electricity for months and made Dominica’s many mountain roads impassable.

“It’s hard for anyone to imagine how devastating Maria was,” said Mr. Walsh, the divemaster, who owns Nature Island Dive on the Soufrière waterfront. “It came at sunset, and by the time the sun rose the next day there were no leaves on the trees, no green, everything was either collapsed or deforested.”

Like many locals, Mr. Walsh was left homeless, without food or water. Also like many locals, he soon heard directly from Mr. Langlois. “He asked what I was going to do, whether I was going to stay in Dominica,” Mr. Walsh said. “And said he wanted to start something called Resilient Dominica to help the community immediately and make it more resilient so we’re not so badly off in the future.”

Simon Walsh lost his diving business in the 2017 hurricane and came to work for Mr. Langlois.

His diving business temporarily destroyed, Mr. Walsh signed on as project manager. They started small, with a school lunch program, and moved into supplying solar-powered lights so kids could study at night. Then they tackled a bigger goal: rebuilding the Soufrière Primary School.

Mr. Langlois brought the same fastidiousness he relied upon at his resort property, which he had named Coulibri Ridge. He picked paint colours in accordance with where the sun hit at certain times of day (he gave the teachers final say) and insisted on expensive concrete roof panels.

“He said we’re not using plywood because it’s not resilient. We’re using the stuff we use on skyscrapers in Montreal,” Mr. Walsh said.

Former U.S. president Bill Clinton toured the final product, and World Central Kitchen, founded by celebrity chef José Andrés, partnered with Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s charitable foundation to build a commercial kitchen in the school capable of feeding thousands of people in the event of another natural disaster.

Resilient Dominica, shortened to REZDM, built a jetty in the neighbouring village of Scotts Head to allow for disaster evacuations, protected turtle nesting grounds and, more recently, helped stave off stony coral tissue loss disease, a coral-killing malady related to rising sea temperatures. For her part, Ms. Marchand threw her energy and funds into establishing the Dominica Humane Society.

For all its enchantments, Dominica has its share of frustrations. Washed out roads go years without repair. The electrical grid is temperamental. The pro-democracy non-profit Freedom House has voiced concerns about the country’s election management and judicial efficiency, and about alleged corruption in its government.

Mr. Langlois initially planned to finish Coulibri Ridge within five years. But he was basing his timeline on construction projects he had overseen in Montreal. Island crews worked at a more leisurely pace, and the island government never seemed completely onside.

By the time Maria hit, he had spent close to 20 years on the project. In 2018, he hired a Canadian construction manager, Neil Suter, to oversee the finishing of work on the resort.

The long-time contractor had been teaching construction at a London, Ont., college. He and his wife had long planned to retire in Dominica. The job was an opportunity to accelerate that timeline.

As much as Mr. Suter liked the couple behind Coulibri Ridge, and the resort’s blissful surroundings, there was one thing about the job that bothered him from the start.

In 2011, Mr. Lehrer, who is originally from New Jersey, had bought Bois Cotlette, the defunct plantation located along the public road leading to Coulibri Ridge. He and his family had painstakingly reclaimed the plantation from the jungle and established a chocolate and cocoa farm that drew tourists eager for a glimpse at the region’s colonial past.

That was all fine by Mr. Suter. What irritated him was Mr. Lehrer’s attitude toward anyone who drove or walked the road leading through Bois Cotlette, called Morne Rouge Public Road. It was the only route to Coulibri Ridge.

The sign at the entrance to Bois Cotlette bills it as 'one of the oldest French plantations on Dominica.'

In a sworn statement taken as part of an eventual lawsuit brought by Mr. Langlois against Mr. Lehrer, the Canadian construction manager said Mr. Lehrer and his wife, Victoria, had repeatedly stopped vehicles travelling on the road. On one occasion, Mr. Lehrer had halted a container truck travelling ahead of Mr. Suter on its way to Coulibri Ridge. When Mr. Suter stepped out of his vehicle to check on the situation, Mr. Lehrer “started to shout at me and told me not to speak to him on his property although I was on the public road,” Mr. Suter told the court. “He was very aggressive to me and took my phone away.”

Local police were able to get the phone returned. A video of the encounter was played in court. In four years of working at Coulibri, Mr. Suter said, he had made four such police reports. But police rarely offered assistance.

The Bois Cotlette owners accosted locals as well. Mr. Suter filmed one instance of Ms. Lehrer yelling at a Soufrière resident walking along the road. She accused the man of poisoning her dogs.

It’s unclear from court documents how Mr. Lehrer defended his efforts to obstruct the road. A court decision mentions that he had sought to make a counterclaim of negligence and nuisance against Mr. Langlois. Container trucks supplying Coulibri Ridge had to drive perilously close to some Bois Cotlette historical ruins as they navigated the disputed road, but Mr. Suter told The Globe and Mail he saw no evidence that the traffic had damaged the structures.

On Oct. 18, 2018, Mr. Lehrer escalated the dispute “by placing boulders across the road, digging a trench across the said road, erecting metal pipes and placing equipment and supplies on the road,” according to a court ruling.

Mr. Suter told The Globe that the public works department eventually showed up to clear the road, but didn’t bring any machinery. Mr. Suter ended up moving the boulders with a piece of construction equipment owned by Coulibri Ridge, he said.

After the blockade, Mr. Langlois applied for a court injunction against any further obstructions and sued Mr. Lehrer for interfering with his economic interests.

The injunction was granted in 2018 and extended in a 2019 decision by the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court, which noted Mr. Lehrer had proposed a bypass that would have routed vehicles around the ruins on the Bois Cotlette property. But the court decision says Mr. Lehrer had denied entry to engineers sent to assess the viability of the bypass.

A trial was held in May, and a decision in the case is imminent.

Blackened auto parts are still visible at the car-crash site on Dec. 13, less than two weeks after villagers found the wreck while walking to work.

By 2021, Mr. Suter said, the continual struggle of driving to Coulibri Ridge from Soufrière had started to wear on him.

Mr. Lehrer’s business model did little to ease his anxieties. The Bois Cotlette website invites investment from “preppers” looking for an escape from “economic or political turmoil, a prolonged natural disaster, or another possible scenario.”

“Bois Cotlette defines preparedness,” it says, “and is the best hedge against crisis in our complex world.”

Bois Cotlette had been approved as a real estate project under Dominica’s Citizenship By Investment program. The government-run scheme grants Dominican citizenship to applicants who invest at least US$200,000 in approved real estate projects in the country. Revenue from this accounts for up to 30 per cent of the country’s GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund. Only 10 or so projects have government approval at any one time, granting them special status.

It’s unclear how successful Mr. Lehrer was at soliciting investments. Bois Cotlette no longer appears as an approved project on the government’s Citizenship by Investment website, but it was listed as recently as October, according to web pages saved by the Internet Archive. The 2022 annual report for Mr. Lehrer’s business, which is registered in Puerto Rico, reports a total business volume of less than $3,000,000, but provides few other details.

Mr. Suter left Coulibri Ridge in December, 2021.

“I did not want to work for Daniel any more because of having to travel that road,” he said.

'They just treated me like another friend,' Kerry Alleyne says of Mr. Langlois and Ms. Marchand, who he had known since childhood.

Last month, Kerry Alleyne, one of the operators of Soufrière Outdoor Center, took Mr. Langlois and Ms. Marchand for a kayak trip to a secluded beach near Pointe Guignard, a popular diving area and turtle nesting site.

Mr. Alleyne had been close with the couple since he was a boy. But their November sojourn was the happiest he’d seen them. “They just treated me like any other friend,” he said. “We were racing and playing the whole way.”

They were different than other wealthy foreigners who came to town, he said. They always supported local businesses, among them some of Mr. Alleyne’s ventures.

By late this year, the couple had every reason to be happy. Mr. Langlois was 66 years old, and Ms. Marchand was 58. Coulibri Ridge had officially opened to rave reviews, including one from The Globe.

A sign points the way to the resort on the road Mr. Langlois and Ms. Marchand had to take to and from Coulibri Ridge.

On Nov. 30, a Thursday, Mr. Langlois and Ms. Marchand drove to Soufrière to buy meals from their favourite local cook.

They left her kitchen in the late afternoon and drove their Nissan up the twisty Morne Rouge. Somewhere around the entrance to Bois Cotlette, the couple were shot, police say. Investigators would later find a single bullet hole in the Nissan’s trunk.

On the evening of Dec. 1, officers rolled onto the Bois Cotlette estate, and took Mr. Lehrer and his wife into custody, along with a visitor named Robert Snyder. A self-proclaimed mechanic from St. Petersburg, Fla., Mr. Snyder had arrived on Nov. 15 and was scheduled to leave the island Dec. 6.

When police took Mr. Snyder into custody, they noticed severe burns on his arm and leg. Mr. Lehrer and Mr. Snyder were later charged with murder. They have yet to enter a plea. Their lawyer did not respond to a request for comment. Ms. Lehrer was released without charge.

Robert Snyder and Jonathan Lehrer arrive at the Roseau courthouse where they were charged in connection with the Canadians' killings.EmoNews

A few days later, a court ordered investigators from Dominica’s Customs and Excise Division to transport Mr. Lehrer from his cell to Bois Cotlette for a search of the property. The move enraged locals, who claimed he was receiving preferential treatment because of his government connections. The lead homicide investigator, Mr. James, said Mr. Lehrer was brought to Bois Cotlette as part of an investigation unrelated to the alleged murders. Mr. James would not discuss the substance of this other investigation.

Video from the search later circulated on social media. It shows a vast network of underground tunnels housing several shipping containers.

Although the murder charges have not been tested in court, many residents of the island believe the dispute between Mr. Lehrer and Mr. Langlois is what led to the deaths, and they are now angry that government authorities didn’t intervene earlier.

“We let it be handled in the courts,” Mr. Alleyne said. “That’s why the village is so upset now. We should have dealt with it ourselves.”

Islanders said they had little faith in the ability of Dominica’s police to put together a solid case. Some said they feared government interference.

Dominican Prime Minister Rosevelt Skerrit announced Tuesday that the government would be appointing a special prosecutor to handle the case.

In Soufrière, it was often Mr. Langlois and Ms. Marchand, and not government officials, who stepped in with money and expertise.

Now, several projects are in limbo. Mr. Langlois had wanted to build an eco-friendly marina in Scotts Head. Phase two of the successful coral rehabilitation program, led by Mr. Walsh, was still in the proposal phase. And the Dominica Humane Society has lost its chief funder.

The couple invested in resilience, a quality the village will need as it moves forward without its main benefactors. “We won’t let them down,” Mr. Alleyne said. “They had confidence in us. Now we have to have that same confidence in ourselves.”

With a report from Stephanie Chambers