This story was produced in collaboration with the Outlaw Ocean Project, with contributions from Joe Galvin, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Jake Conley, Austin Brush and Daniel Murphy.

It had been a successful year for Donggang Jinhui Food. In 2022, the seafood processing company, located in Dandong, China, had opened a large plant at its compound in the city, and doubled the amount of squid it exported to the United States.

So the company threw a party. Videos of the February, 2023, event, posted on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, show singers, instrumentalists, dancers, fireworks and strobe lights. They also show evidence of a crucial aspect of the company’s success: its use of North Korean workers, who are sent by their government to work in Chinese factories, in conditions of captivity.

At the party, the company played pop songs popular in Pyongyang, including People Bring Glory to Our Party, written by North Korea’s 1989 poet laureate, and We Will Go to Mount Paektu, a reference to the widely mythologized birthplace of Kim Jong Il, the former North Korean ruler and father of current ruler Kim Jong Un. In the audience, dozens of workers swayed to the music, waving miniature North Korean flags.

Drone footage played at the event showed off the company’s eight-hectare, walled-in compound, which has processing and cold-storage facilities and a seven-floor dormitory for workers. A video shown to attendees highlighted the company’s expanding customer base in the West, and noted a wide array of Western certifications, from companies such as the Marine Stewardship Council and Sedex, which are supposed to check workplaces for abuses.

When the footage was posted online, a commenter – presumably befuddled, because using North Korean labour violates United Nations sanctions – asked, “Aren’t you prohibited from filming this?”

This year, a team of researchers with the Outlaw Ocean Project, a non-profit journalism organization based in Washington, set out to document the use of North Korean workers in Chinese seafood plants that supply major brands in Canada and the United States. They reviewed leaked government documents, promotional materials, satellite imagery, online forums and local news reports. The researchers watched hundreds of cellphone videos published on Douyin, Bilibili (another video-sharing site) and WeChat (a popular Chinese messaging platform).

The entrance to Donggang Xin Xin in late 2023. While visiting the Chinese seafood processing plant an investigator for the Outlaw Ocean Project found hundreds of North Korean women working under a red banner that, in Korean, read, 'Let's carry out the resolution of the 8th Congress of the Workers’ Party.”'© The Outlaw Ocean Project

Reporting in China is distinctly difficult for Western reporters, but the group sent Chinese investigators to visit factories, talk to managers and take videos of production lines. The Outlaw Ocean Project also secretly sent interview questions, through intermediaries, to 20 North Korean workers and four managers, asking about their time in Chinese factories.

In all, the investigation identified 15 seafood processing plants that together have used more than 1,000 North Korean workers since 2017. China officially denies that these workers are in the country. But their presence is an open secret. “They are easy to distinguish,” one Dandong native wrote in a comment on Bilibili. “They all wear uniform clothes, have a leader, and follow orders.”

Although much of the seafood processed at the Chinese plants ended up in the U.S. and Canada, this has largely been hidden from consumers. Because of the opaqueness of international seafood supply chains and the unreliability of third-party auditing services that claim to investigate labour conditions at processing plants, it is often impossible for buyers to know who handled their fish.

A group of North Korean women with their heads down in the streets of Dandong, China in March 2023 being overseen by a government minder.© The Outlaw Ocean Project

The North Korean workers, most of whom are women, described a broad pattern of captivity and violence at the plants. They are held in compounds behind barbed wire, under the watch of security agents. Several described being slapped and punched by managers for not working hard enough or not following orders. They described being subjected to severe punishment if they tried to escape.

“It’s often emphasized that if you are caught running away, you will be killed without a trace,” a worker said.

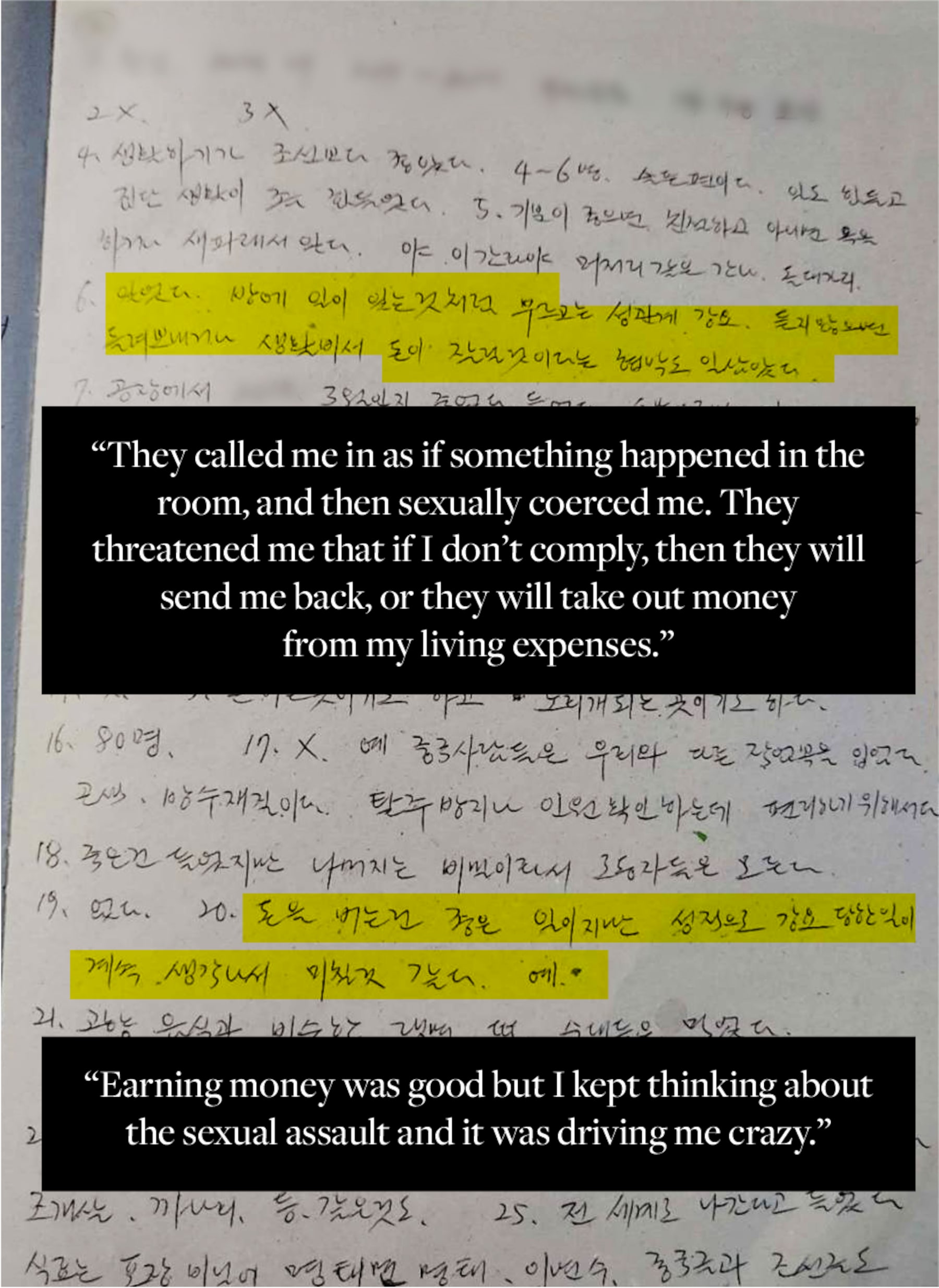

Almost all of them described enduring rampant sexual assault at the hands of their managers, and some said they had been forced into prostitution, or knew others who had been.

“The worst and saddest moment was when I was forced to have sexual relations when we were brought to a drinking occasion,” one worker said.

The Globe and Mail is not naming the workers interviewed for this story because they could face severe repercussions in North Korea or China for speaking to Western media.

The labour program is run by various entities in the North Korean government, including a secretive agency called Room 39, which oversees activities such as money laundering and cyberattacks, and which funds the country’s nuclear- and ballistic-missile programs, according to reports from Ritsumei University and the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, a non-governmental research organization.

North Korea began sending workers in significant numbers to China in 2012, when more than 40,000 were given special visas. A portion of the workers’ salaries is taken by the North Korean government. This funds Room 39′s activities, and provides a vital source of foreign currency for the country’s officials.

In 2012, the North Korea Strategy Center, a Seoul-based research and advocacy group, estimated that the country made between US$1.2-billion and US$2.3-billion annually through the program.

In 2017, after North Korea tested a series of nuclear weapons, the UN imposed sanctions that made it illegal for foreign companies to use North Korean workers, on the grounds that their labour was coerced, and that their salaries were funding the country’s authoritarian regime.

At the Donggang Haimeng Foodstuff plant in Dandong, a North Korean manager's office is sparsely decorated with portraits of past North Korean leaders.© The Outlaw Ocean Project

Despite the attempted crackdown, China has continued to import North Korean workers, who provide cheap labour, typically at about a quarter of the cost of local employees. According to U.S. State Department estimates, there are upwards of 100,000 North Koreans working in China, many at construction companies, textile factories and software firms.

And many process seafood. In 2022, according to information from Chinese officials who were running pandemic quarantines, there were some 80,000 North Koreans just in Dandong, a hub of the seafood industry located on the Yalu River, along the North Korean border.

In late 2023, an investigator hired by the Outlaw Ocean Project visited a Dandong plant called Donggang Haimeng Foodstuff, and found a North Korean manager sitting at a wooden desk with two miniature flags, one Chinese and one North Korean. The walls behind the desk were bare except for two portraits of past North Korean leaders Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il.

The manager took the investigator to the workers’ cafeteria to eat a North Korean cold-noodle dish called naengmyeon, and then took him on a tour of the processing floor. Several hundred North Korean women dressed in head-to-toe red uniforms, pink aprons and white rain boots stood shoulder-to-shoulder at long metallic tables under harsh lights, hunched over plastic baskets of seafood, slicing and sorting the products by hand.

The factory has exported thousands of tons of pollock to importers that supply major U.S. retailers, including Walmart and ShopRite.

Walmart and ShopRite did not respond to requests for comment. Donggang Haimeng said only that it had not hired North Korean workers.

In late November, after investigators had visited several seafood processing plants in Dandong, local authorities distributed pamphlets with a stern warning. Workers who were found to be co-operating with foreign media outlets, it said, would face charges under the Anti-Espionage Act.

Frozen fish products from High Liner Foods Inc. and Aqua Star are pictured in a Toronto grocery store. High Liner is the fourth largest seafood supplier in North America, and the Canadian branch of Aqua Star sells branded seafood products at Walmart, Metro, Sobeys, and Giant Tiger.Laura Proctor/The Globe and Mail

Canada imports significant amounts of seafood produced with forced North Korean labour.

Nova Scotia-based High Liner Foods, the fourth largest seafood supplier in North America and a publicly traded company, sources seafood products from Dalian Haiqing, one of the plants the Outlaw Ocean Project visited. There were an estimated 50 to 70 North Korean workers on site.

Dalian Haiqing said it “does not employ overseas North Korean workers.”

High Liner was previously found by the Outlaw Ocean Project to source products from plants using forced labour from Uyghurs, an ethnic minority in China. The company sells white fish products to Walmart, Costco, Loblaws, Safeway, Kroger and Amazon.

In a statement, High Liner confirmed it had purchased products from Dalian Haiqing, but said third-party audits had indicated “no presence of North Korean labour.” It added that it has since received “repeated written and verbal confirmations from the supplier that North Korean labour is not being used in their plants.”

Even so, High Liner said it was initiating an investigation into the allegations concerning Dalian Haiqing and was “suspending all business dealings with them effective immediately while further information is gathered and assessed.”

Dalian Haiqing is a major supplier to many other Canadian food companies, among them the Canadian branch of the seafood company Aqua Star, which sells branded seafood products at Walmart Canada, Metro Canada, Voilá, Giant Tiger and Powell’s Supermarket.

Walmart Canada, Voilá, Giant Tiger and Powell’s Supermarket did not respond to requests for comment. Metro Canada said in a statement that its suppliers are “required to respect working conditions across the supply chain as outlined in our Supplier Code of Conduct for responsible procurement.”

The company added that it assesses suppliers’ adherence to the code of conduct using a third-party platform. “Through this program, we have confirmed that Aqua Star’s practices are in line” with the code of conduct, it said.

The entrance to the Dandong Taifeng plant in northeastern China, which supplies tens of thousands of tons of seafood to grocery stores in the U.S. and other countries. An Outlaw Ocean investigator found one hundred-fifty North Koreans working on the processing floor.© The Outlaw Ocean Project

Frobisher International Enterprise, a Canadian seafood distributor, has imported seafood from a different source the Outlaw Ocean Project also found to have employed forced North Korean labour: Dandong Taihua Foodstuff. Frobisher International supplies Ocean Mama-branded frozen clam meat to multiple local and regional sellers in Canada, including Al Premium Foods, Choices Market and Dong Phuong Distributor. None of these companies responded to requests for comment.

Companies often claim they are in compliance with labour standards because they have passed “social audits,” which are conducted by firms that inspect work sites for abuses. But these audits are of dubious value.

Half of the plants researchers found to be using North Korean workers were certified by the Marine Stewardship Council, a sustainability group, which only grants certification if companies have passed social audits or other assessments. Jackie Marks, the MSC’s head of public relations, said these social audits are conducted by a third party, not by the organization.

Skepticism of such audits is growing. In 2021, the U.S. State Department said these audits, especially in China, are inadequate for identifying forced labour because auditors rely on government translators and rarely speak directly to workers.

Auditors are also reluctant to anger the companies that have hired them, and workers face reprisals for reporting abuses. Chris Smith, a U.S. Congressman and a specialist on China, noted, “Social audits at plants in China create a Potemkin village, and American seafood companies who go along with them should know better.”

The U.S. and Canada have attempted to combat the use of forced labour in China with import laws. The U.S. passed a strict law in 2017 called the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, which levies heavy fines on companies that import products tied to North Korean labour. The law established a “rebuttable presumption” that categorizes work done by North Koreans as forced labour unless proven otherwise.

As part of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, the trade deal that replaced NAFTA, Canada committed to banning imports made with forced labour. The federal government amended the Customs Tariff Act in 2020 to include such a ban, but that law does not contain anything similar to the rebuttable presumption in the American legislation. As of late last year, Canadian authorities had not stopped a single shipment of forced-labour goods from entering Canada since the rules took effect.

Dandong, a city of two million people, is linked to the North Korean city of Sinuiju by the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge, which spans the border. The bridge is one of the Hermit Kingdom’s few gateways to the rest of the world; about 70 per cent of all the goods exchanged between the two countries travels across it.

The North Korean government carefully selects workers to send to factories in Dandong and elsewhere in China. The process is typically overseen by officials from Room 39, who strenuously screen applicants’ political loyalties to reduce the risk of defections.

Applicants are even screened for height: the country is chronically malnourished, and the state prefers candidates who are taller than five-foot-one, to avoid the official embarrassment of being represented abroad by short people, according to Remco Breuker, a North Korea specialist at Leiden University in the Netherlands. The North Korean government did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Once selected, applicants go through predeparture training, which can last a year and often includes government-run classes covering everything from Chinese customs and etiquette to “enemy operations” and the activities of other countries’ intelligence agencies, according to Mr. Breuker and a 2023 report from the South Korean government.

A North Korean minder ushers a group of North Korean women into a restaurant on the streets of Dandong, China in March 2023. The use of such workers in China is in violation of U.N. sanctions.Living in North Korea/© The Outlaw Ocean Project

To route workers to Chinese seafood companies, North Korea’s Department of Fisheries co-ordinates with China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, according to a memo published by the agencies. These agencies did not respond to requests for comment.

The logistics are often handled by private Chinese “dispatch” companies, and placements are sometimes negotiated online. In a video posted on Douyin this past September, for example, an uploader announced the availability of 2,500 North Koreans who “want to find some manual work.”

A commenter asked if they could be sent to seafood factories across the border in Dandong, and the poster agreed. Another post recently advertised the availability of 5,000 North Korean workers and received 21 replies. “Are there any leaders who can speak Mandarin?” one commenter asked, to which the author replied, “There is a team leader, management and a translator.”

Jobs in China are coveted in North Korea, because they often come with contracts promising monthly salaries of US$270, compared to the US$3 a month paid for similar work in North Korea. Workers who are selected sign two- or three-year contracts.

But when they arrive in China, managers typically confiscate their passports. If workers attempt to escape or complain to people outside the plants, their families at home can face reprisals from the government. Inside the factories, North Korean workers wear uniforms that are a different colour than those worn by Chinese workers. “Without this,” a plant manager who worked at Donggang Jinhui Food for several years said, “we can’t tell if one disappears.”

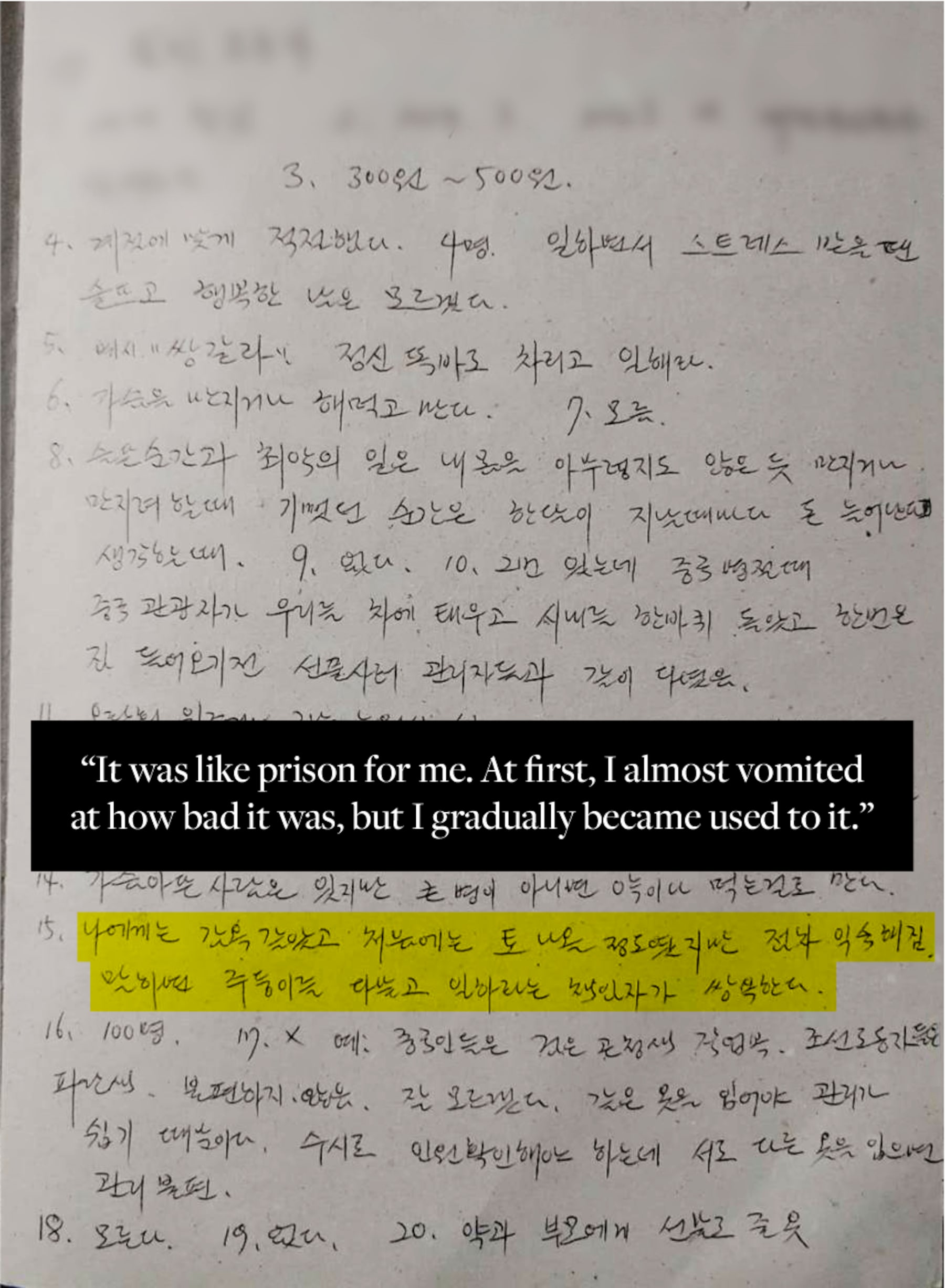

The work itself is relentless. Shifts at the seafood plants run 14 to 16 hours. Many workers receive at most one day off a month and few, if any, holidays or sick days. The women sleep in bunk beds in locked dormitories, sometimes with 30 people per room.

Workers are forbidden from tuning in to local TV or radio and from leaving factory grounds unaccompanied. Mail is scrutinized by North Korean security agents who also “surveil the daily life and report back with official reports,” a manager who spent several years at a plant in China’s Dalian region said.

Workers typically see less than 10 per cent of their promised salaries. One contract reviewed by the Outlaw Ocean Project said that US$40 would be deducted each month to pay for food; more is deducted for electricity, dorms, heating, water, insurance and “loyalty” payments to the government. What is left is often less than US$30 a month.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to questions for this story. In the past, however, the government has pushed back against criticisms of its relationship with North Korea. The Chinese ambassador to the UN wrote last year, in a letter to the UN, that China has abided by sanctions even though it has sustained “great losses” as a result, and insisted that it has conducted “thorough investigations” into allegations of non-compliance.

Western journalists are barred from entering North Korea, and citizens of the country are strictly prohibited from talking to reporters.

But the Chinese investigators who worked with the Outlaw Ocean Project have contacts in North Korea whom they employ to get information out of the country. With their help, the project’s researchers compiled a list of two dozen North Koreans who had been dispatched to China, most of whom have since returned home. The workers and managers were a range of ages, came from a variety of regions in the country, and had worked for at least a half dozen Chinese factories.

The Outlaw Ocean Project sent a list of questions, through the investigators, to their contacts in North Korea. These contacts then met with the workers to interview them in secret. The interviews were conducted individually so the workers would not know the identities of others who were speaking, or what they said. The meetings typically occurred in open fields, parks or in the street, where it’s tougher for security agents to use bugs to conduct surveillance.

All of the workers were told their responses would be shared publicly by an American journalism outlet. They faced considerable risk speaking. Experts say they would likely be executed if caught, and their families put in prison camps. But they agreed to talk because they believe it is important for the rest of the world to know about what happens to workers who are sent to China.

North Korean contacts transcribed the workers’ answers by hand, and then took photos of the questionnaires and sent them, using encrypted online tools and satellite phones, to the investigators, who sent them to the Outlaw Ocean Project. (Workers and managers in China were interviewed in similar fashion.)

Because of these layers of protections, it is impossible to fully verify the content of the interviews. But experts reviewed the responses to make sure they are consistent with what is known about the work-transfer program, and with interviews with North Korean defectors. (More than two months after this process was completed, the reporting team checked on the interviewers and interviewees, and everyone was still safe.)

In their answers, the workers described crushing confinement and deep loneliness. The work was gruelling, the factories smelled and violence was common. “They kick us and treat us as subhuman,” a worker who spent four years at a seafood plant in Dandong wrote.

Asked if they could recount any happy moments, most said there had been none, but almost all had sad moments to recount. One, who recently returned to North Korea, said her experience at a Chinese plant made her feel like she “wanted to die.”

The most striking pattern was the women’s descriptions of sexual abuse at the plants.

Of 20 workers interviewed, 17 of them said they had been sexually assaulted by plant managers. “When he doesn’t get his way [sexually], he gets angry and kicks me,” a worker said of her manager.

Three of the women said their managers had forced them into prostitution. “Whenever they can, they flirt with us to the point of nausea and force us to have sex for money, and it’s even worse if you’re pretty,” a woman who was at Dalian Haiqing Food for more than five years told me. A worker who was at the Jinhui plant for years said, “Even when there is no work during the pandemic, the state demands foreign currency funds out of loyalty, so managers force workers to sell their bodies.” (Jinhui did not respond to requests for comment.)

The pandemic made life more difficult for many of the women. When China closed its borders, some found themselves trapped far away from home. Often their workplaces shut down, and they lost their incomes. North Korean workers frequently have to pay bribes to government officials and labour brokers in control of hiring to secure posts in China.

Many have to hire loan sharks to borrow the funds needed for bribes. These loans, typically around US$1,500, can come with interest rates up to 10 per cent. When work was paused in China, North Korean workers were unable to pay back their loans. As a result, the North Korean loan sharks sent groups of local thugs to the homes of workers’ relatives to intimidate them. Some of the workers’ families had to sell their homes to settle up. In 2023, two North Korean women at textile plants killed themselves.

Pandemic restrictions in China were eased this past year, and the border between China and North Korea reopened. This allowed many of the North Koreans to return home. In August, 2023, roughly 300 North Korean workers boarded 10 buses in Dandong to go back. Police officers dispatched by the Dandong Public Security Bureau lined up around the buses to prevent defections and keep Chinese onlookers back.

In photos and a video reviewed by the Outlaw Ocean Project, some of the women can be seen hurriedly loading large suitcases onto a neon green bus, then riding away across the Friendship Bridge. Similarly, in September, about 300 North Koreans boarded a passenger train for the journey from Dandong to Pyongyang. That same month, roughly 200 North Korean workers were repatriated on a flight operated by Air Koryo, the main North Korean airline.

As 2023 drew to a close, the Chinese and North Korean governments began negotiating over the next wave of workers to be dispatched to Chinese factories. According to Hyemin Son, a North Korean defector who works for Radio Free Asia, North Korean labour brokers requested that Chinese companies pay an advance of about US$130 per worker. The price had gone up, one labour broker told her, because “Chinese companies cannot operate without North Korean manpower.”

WATCH:

An investigation by the Outlaw Ocean Project reveals that China uses thousands of workers from North Korea in its seafood industry. Many at the seafood processing plants recount long shifts, labour abuses and sexual assault.

The Outlaw Ocean Project

This story was produced in collaboration with the Outlaw Ocean Project, a non-profit journalism organization in Washington.