Hirtles Beach is a popular destination for swimming and enjoying the sun south of Lunenburg, N.S. But in a scenario where greenhouse gas emissions are high, parts of the beach could recede 40 to 180 metres inland by the end of this century, potentially destroying homes near the shore.Matthew McClearn/The Globe and Mail

Graphics by John Sopinski

Sandy beaches are in constant motion. The wind and waves redistribute sand. Ocean currents carry it along the beach. Storm surges overwash and reshape. Eroding cliffs and nearby rivers bring fresh sediment. In his 1998 book The Living Beach, author Silver Donald Cameron wrote that many coastal geologists and other scientists who study beaches describe them as evolutionary processes – and in a sense, they’re alive.

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reiterates what has been long understood: Sea level rise has accelerated considerably in recent decades. The global average sea level has increased by about 20 centimetres since the beginning of the 20th century, the biggest rate of increase in 3,000 years. It’s virtually certain that it will continue rising for the balance of this century, and likely for centuries to come. Consequently, beaches – which comprise roughly one-fifth of the world’s coasts – will increasingly march in a single direction: inland. They’re also expected to be battered by intensifying waves and storm surges in many areas as the climate warms. High water extremes that once had a likelihood of happening once a century may become annual events in some coastal areas by 2050, and in the majority of coastal areas by 2100, the IPCC report notes. This spells dramatic change for those living on or near Canada’s coasts. Many beaches are projected to erode dramatically in coming decades – in some cases, by hundreds of metres.

Researchers are still debating what those transformations will look like. According to a study published last year by the European Commission Joint Research Centre (JRC), almost half of the world’s sandy beaches face “near extinction” over the next 80 years if greenhouse gas emissions continue on a “business-as-usual” trajectory. This finding provoked a dustup in the coastal morphology field: Critics of the JRC report argued most beaches will migrate (significantly, in some cases) but will otherwise look more or less the same as before. Either way, the implications for coastal communities will be profound.

“This is not about alarming and scaring people,” says Michalis Vousdoukas, a coastal oceanographer and the JRC paper’s lead author. “Technical solutions exist for sustaining the coast for countries like Canada that have the economic capacity to react.” The JRC also projected that with “moderate” emissions mitigation, shoreline retreat could be reduced by as much as 40 per cent.

“The faster we act, the better,” he says.

The JRC’s models predict Canada will lose between 6,400 and 14,400 kilometres of sandy beach by 2100 – more than Chile, Mexico, China and the United States. (Only Australia is expected to lose more.) The JRC’s calculations excluded expansive swaths of Canada’s northern coastline, because its results weren’t valid for oceans locked for months by sea ice.

Canada’s high ranking on this list isn’t surprising: Its total ocean coastline has been estimated at 243,000 kilometres, the longest of any country. (Shoreline lengths are not absolute; the closer you zoom in on a map, the longer the coastline measures, as smaller and smaller inlets and other features become visible.)

But the sheer length of affected beaches might not be the best way to determine a country’s vulnerability. An estimated 600 million people live in coastal areas located less than 10 metres above sea level. And 15 of the world’s 20 megacities (those with populations greater than 10 million) are found on the coast. On the extreme, some small island countries are almost completely surrounded by vulnerable sandy beaches, with Marshall Islands, Maldives, Kiribati and Tuvalu among the most vulnerable places on Earth.

In contrast, most of Canada’s sandy beaches are found in sparsely populated areas. There’s simply more land available for mass relocation of people, homes and infrastructure. And few of Canada’s beaches are of international renown, since frigid coastal waters reduce their appeal as tourist destinations. Simply put, fewer people will mourn our beaches’ retreat.

But that’s little comfort to people who live on the north shore of Prince Edward Island and other vulnerable communities across the country.

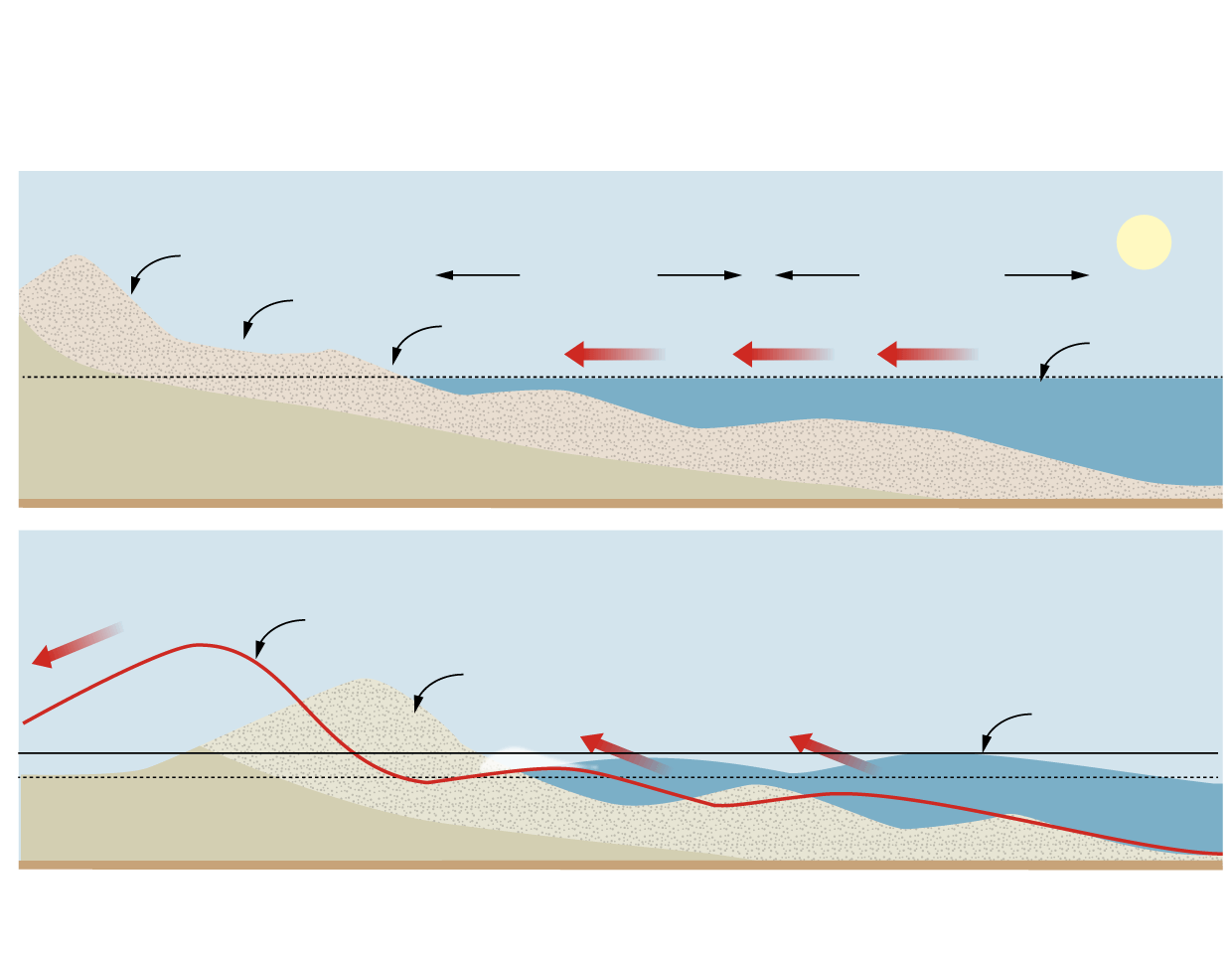

How beaches retreat

Beaches are in constant motion, their position

determined by processes that move sediments

offshore and those bringing them back.

They’re continually reshaped by waves,

currents, winds and other forces – but in the

long run, sea level is the most important of all.

Components and processes on a sandy beach

Foredune

Inner surf

Outer surf

Berm

Swash

Sea level

Trough

Bar

Swash and backwash reshape the beach every day.

Beach retreat

New beach and foredune

New sea

level

Old foredune

Higher sea level usually causes the beach and foredune

to migrate landward. But unless humans interfere, much

of the eroded sand remains on the beach.

JOHN SOPINSKI and matt mcclearn/THE GLOBE

AND MAIL, SOURCE: introduction to Coastal

Processes and Morphology, by Robin

Davidson-Arnott

Beaches are in constant motion, their position deter-

mined by processes that move sediments offshore and

those bringing them back. They’re continually reshaped

by waves, currents, winds and other forces – but in the

long run, sea level is the most important of all.

Components and processes on a sandy beach

Foredune

Inner surf

Outer surf

Berm

Swash

Sea level

Trough

Bar

Swash and backwash reshape the beach every day.

Beach retreat

New beach and foredune

Old foredune

New sea level

Higher sea level usually causes the beach and foredune to

migrate landward. But unless humans interfere, much of the

eroded sand remains on the beach.

JOHN SOPINSKI and matt mcclearn/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: introduction to Coastal Processes and

Morphology, by Robin Davidson-Arnott

Beaches are in constant motion, their position determined by processes that move sedi-

ments offshore and those bringing them back. They’re continually reshaped by waves,

currents, winds and other forces – but in the long run, sea level is the most important of all.

Components and processes on a sandy beach

Foredune

Inner surf

Outer surf

Berm

Swash

Sea level

Trough

Swash and backwash reshape

the beach every day.

Bar

Higher sea level usually causes the beach

and foredune to migrate landward. But

unless humans interfere, much of the

eroded sand remains on the beach.

Beach retreat

New beach and foredune

Old foredune

New sea level

JOHN SOPINSKI and matt mcclearn/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: introduction

to Coastal Processes and Morphology, by Robin Davidson-Arnott

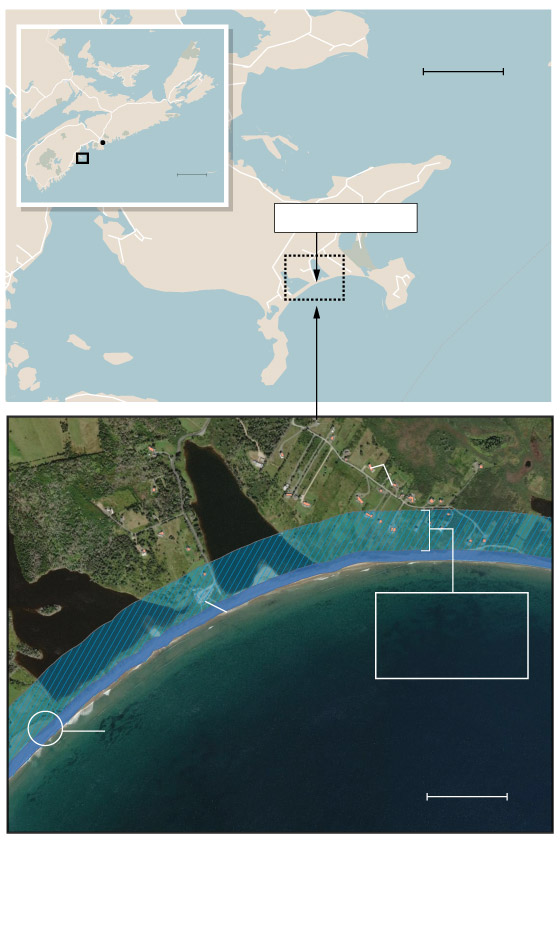

Case study: Hirtles Beach, N.S.

0

2

PEI

KM

NOVA SCOTIA

Rose Bay

Halifax

0

75

Detail

KM

Kings Bay

Hirtles Beach

NOVA

SCOTIA

Moshers

Bay

Hartling Bay

Houses

Hirtles Beach

Hirtles

Pond

Romkey

Pond

Likely range

of beach retreat

Parking lot

Hartling Bay

As it erodes, this

drumlin supplies

sediment to the beach.

0

1

KM

matt mcclearn and JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND

MAIL, SOURCE: esri; European Commission Joint

Research Centre; TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU; microsoft

0

2

PEI

KM

NOVA SCOTIA

Rose Bay

Halifax

0

75

Detail

KM

Kings Bay

Hirtles Beach

NOVA

SCOTIA

Moshers

Bay

Hartling Bay

Houses

Hirtles Beach

Hirtles

Pond

Romkey

Pond

Likely range

of beach retreat

Parking lot

Hartling Bay

As it erodes, this

drumlin supplies

sediment to the beach.

0

1

KM

matt mcclearn and JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND

MAIL, SOURCE: esri; European Commission Joint

Research Centre; TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU; microsoft

0

2

PEI

KM

Rose Bay

NOVA SCOTIA

Conrad

Island

Halifax

0

75

Detail

KM

Hirtles Beach

Kings Bay

NOVA

SCOTIA

Moshers

Bay

Hartling Bay

Houses

Hirtles

Pond

Hirtles Beach

Romkey

Pond

Likely range

of beach retreat

Parking lot

Hartling Bay

As it erodes, this

drumlin supplies

sediment to the beach.

0

1

KM

matt mcclearn and JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: esri;

European Commission Joint Research Centre; TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU; microsoft

Canada’s threatened beaches

Rising sea levels act on beaches so gradually that at the historical rates we’ve become accustomed to, the resulting changes have often been barely perceptible. A case in point: Surveys conducted by the Geological Survey of Canada during the second half of the 20th century found that Hirtles Beach, on the Atlantic Coast just south of Lunenburg, N.S., had been “fairly stable.”

But something has changed since then. At the turn of the century, two weathered concrete pillars stood surrounded by sandy soil and beach grasses. They belonged to an ill-advised rock-crushing operation in the 1940s that carted off untold truckloads of cobbles, pebbles and sand. But the shoreline has retreated inland by several metres in recent years, leaving the pillars’ foundation lying off kilter above the high-tide mark.

Any acceleration of sea-level rise could have dramatic consequences for places like Hirtles. As Mr. Cameron wrote in The Living Beach, “sea level is the slowest, the least perceptible and the most important of all the factors that are constantly molding the world’s beaches.”

The concrete pillars at Hirtles Beach, shown at top in 1999 and at bottom in August of 2020.Handout; Matthew McClearn/The Globe and Mail

The IPCC has estimated that without major reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, sea levels will rise between 21 and 71 cm globally between now and 2070. That wide range reflects the considerable uncertainties involved, but the IPCC expects sea levels to rise between three and six times as fast as they did over the past century.

The Joint Research Centre incorporated IPCC sea level rise projections into its beach-retreat model. According to The Globe and Mail’s analysis of the resulting estimates, under a high-emissions scenario, Hirtles Beach will retreat by between zero and roughly 100 metres by mid-century, depending on which part of the beach you’re standing on. (This wide estimate, which researchers call “the very-likely range,” reflects uncertainties associated with predicting erosion.) The deterioration will worsen considerably by century’s end: The very-likely range is between 40 and 180 metres, roughly. Homes could be destroyed.

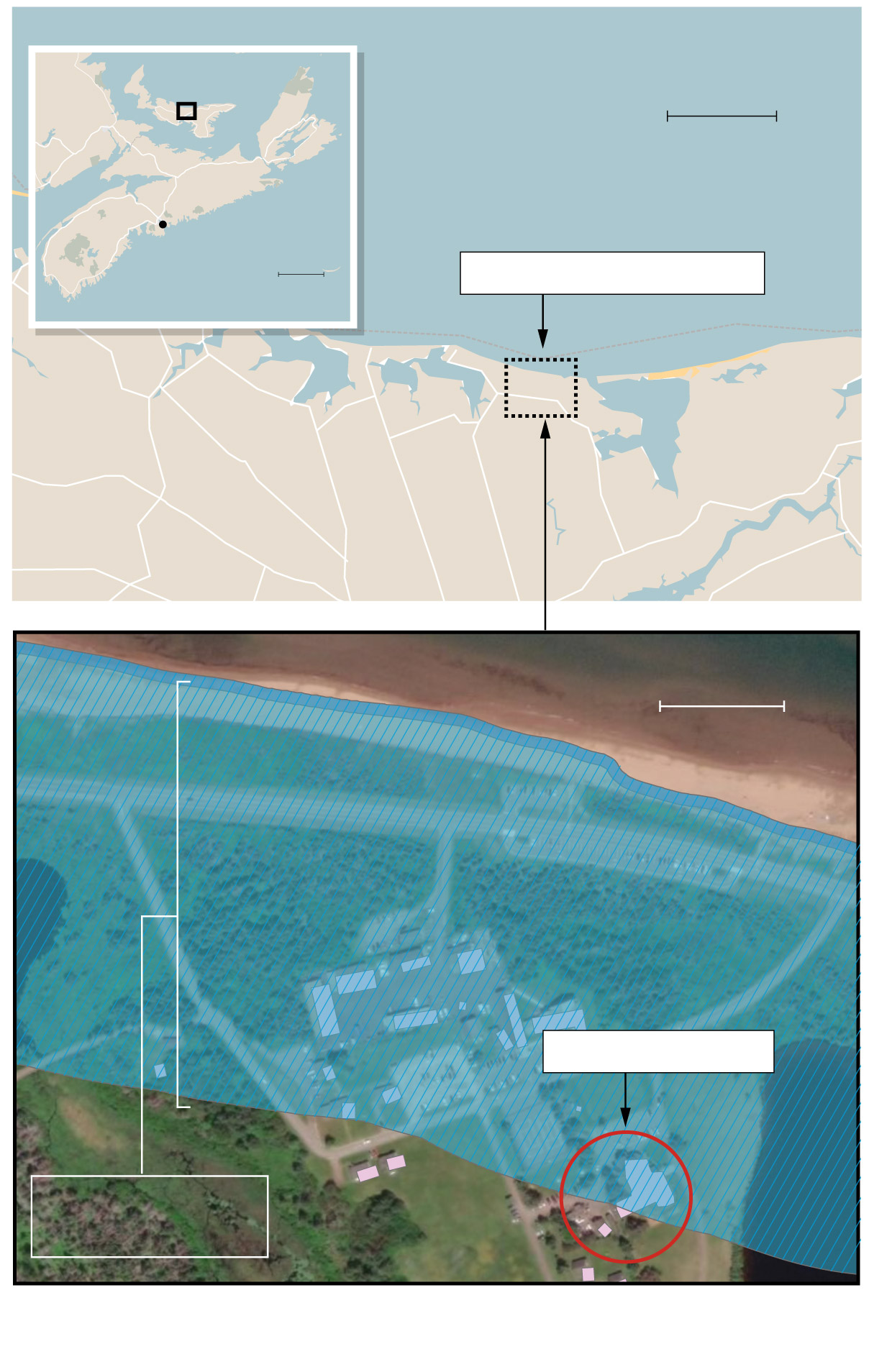

Few places in Canada will be harder hit than PEI. According to the JRC’s projections, a stretch of its northern shore more than 100 km long will retreat, potentially by hundreds of metres. The famous red cliffs and dunes of Prince Edward Island National Park would be obliterated. Dalvay by the Sea, a stately mansion built in 1895 by former Standard Oil president Alexander MacDonald and now a luxury hotel, would be at risk of becoming “Dalvay in the Sea.”

PEI

0

1

KM

Detail

NOVA SCOTIA

Halifax

0

75

Dalvay by the Sea Beach

KM

Dalvay

Lake

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

0

100

METRES

Dalvay by the Sea

Likely range

of beach retreat

matt mcclearn and JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND

MAIL, SOURCE: esri; European Commission Joint

Centre; TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS;

HIU; microsoft

PEI

0

1

KM

Detail

NOVA SCOTIA

Halifax

0

75

Dalvay by the Sea Beach

KM

Dalvay

Lake

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

0

100

METRES

Dalvay by the Sea

Likely range

of beach retreat

matt mcclearn and JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: esri; European Commission Joint Research

Centre; TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU;

microsoft

PEI

0

1

KM

Detail

NOVA SCOTIA

Halifax

0

75

Dalvay by the Sea Beach

KM

Dalvay

Lake

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

0

100

METRES

Dalvay by the Sea

Likely range

of beach retreat

matt mcclearn and JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: esri;

European Commission Joint Research Centre; TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU; microsoft

These projections are far worse than what the island has experienced historically, and also the projections of local researchers.

In 2012, Tim Webster, a research scientist with the Nova Scotia Community College’s Applied Research Group, analyzed aerial photography of the island’s entire coastline collected between 1968 and 2010 to assess its movements. During that period, the mean erosion rate was around 28 cm a year, although it had accelerated to 40 cm in the first decade of this century.

Adam Fenech, director of the University of Prince Edward Island’s Climate Lab, used the same data to project future erosion rates. He determined that 1,000 homes, 17 lighthouses, 146 commercial buildings and 50 km of roads might suffer damage or disappear owing to erosion. “For PEI,” he observed, “that’s a lot of homes.”

Dr. Fenech found the JRC’s more rapid erosion predictions “shocking” and “almost unbelievable.”

“Anne of Green Gables would not recognize her island” if they prove correct, he says.

Daniel Scott, a professor at the University of Waterloo’s geography department who has studied climate-change effects on beaches and tourism, says that before publication of the JRC’s data, global erosion estimates simply weren’t available.

Like Dr. Fenech, Dr. Scott found some of the JRC’s predictions astonishing. But both say detailed localized studies would be required to confirm the results for individual beaches or resorts.

There’s an alarming asterisk accompanying all of this: Critics say the IPCC, in the name of scientific prudence, has vastly understated sea level rise. In his new book Moving To Higher Ground: Rising Sea Level and the Path Forward, oceanographer John Englander explained that the IPCC’s highly conservative protocols (which he finds praiseworthy in most contexts) led the organization to largely ignore the impact of melting land ice in Antarctica.

“Even highly respected research companies and government organizations around the world often look only to the IPCC’s top-line figure of less than one metre as the worst-case scenario for future sea level this century,” Mr. Englander wrote. “Often they don’t notice that Antarctica – which holds 88 per cent of potential SLR – is largely omitted from the projections.”

With continuing evidence of accelerating deterioration of land ice in Antarctica and also Greenland, some researchers project sea level could rise by two, three or even four metres this century. In such scenarios, beach retreat would be far worse.

The human factor

Dr. Fenech and Dr. Scott, neither of whom was involved in building the JRC’s model, praised the effort’s ambition. (Dr. Scott is using the models to help owners and investors of resorts understand how climate change will affect properties in the Caribbean and Thailand.)

“We tried to combine as many drivers of shoreline change as possible,” explained Dr. Vousdoukas, the JRC researcher. Those included sea-level rise, changes in storm ferocity and local topography including beach slope. But he acknowledges the models don’t reflect beach width. (There’s no global dataset available for that.)

Robin Davidson-Arnott, a professor emeritus of geography who has extensive experience in how coastlines evolve, says the JRC’s retreat predictions are in line with previous efforts. “The only issue that comes up is that they equate the recession of the shoreline with a loss of the sediment,” he says.

That’s not a minor point. Dr. Davidson-Arnott says eroding sediment is not lost; it migrates onshore and accumulates on beaches. Though with ample supplies of sediment, say from drumlins (elongated, spoon-shaped hills formed by glaciers) or cliffs, beaches may actually expand seaward even as sea levels rise. More commonly, Dr. Davidson-Arnott predicts Canada’s beaches will retreat inland but will actually have more sand than before, thanks to all the new eroded material.

The same criticism figured prominently in a rebuttal of the JRC’s paper by other researchers, published in October in Nature Climate Change. “Globally, hundreds of beaches have been retreating at rapid rates for more than a century, but have not been extinguished,” they wrote. “As sea level rises, shoreline retreat must, and will, happen. Beaches, however, will survive.”

What all of these researchers agree on, however, is that beaches diminish when humans intervene by building seawalls and other defences. Dr. Vousdoukas and his colleagues point out that human encroachment along shorelines has greatly increased and is expected to continue.

“Once you build a house or wall behind a beach, you set a limit to the maximum possible erosion,” Dr. Vousdoukas says. “Once the ocean starts to reach this boundary that humans created, then most likely you will have severe beach erosion.”

Reefs of sandstone rock protect the beach from the waves in a causeway leading into Souris, PEI.Adam Fenech

Much of Canada’s ocean coastline remains unprotected. Dr. Fenech and colleagues have flown low over PEI’s coastline, cataloguing its defences. They found 172 km of it, primarily armour rock, protecting just 5 per cent of the total coastline. Roughly 11 km of that was installed between 2012 and 2018.

Armouring is more popular along the U.S. Atlantic coast, where its merits and drawbacks have long been on display. “In places like Daytona Beach in Florida, quite often you’ve got a seawall,” Dr. Scott says. Seawalls can hold erosion in check but often damage unprotected shoreline nearby. And new sand must often be dumped periodically on the beach to “nourish” it.

“Without beach nourishment, Miami Beach doesn’t exist,” he says. “So in other parts of the world, there’s a lot less adaptability of their beaches” than in Canada.

Armouring doesn’t last forever. Owners can find themselves locked in an arms race with nature they can’t win.

“You spend $2-million on a seawall and if you’re lucky, in 20 years, you’ve got to replace it,” Dr. Fenech says. “If you’re unlucky, you’ve got to replace it in a year or two. I’ve seen both happen.”

That’s one reason many coastal morphology experts recommend being highly selective when erecting coastal armouring. Their favoured alternative, managed retreat, involves giving way by prohibiting coastal development, and dismantling or moving existing buildings, roads and other infrastructure before they’re threatened – an option that’s often politically unpalatable.

Dr. Davidson-Arnott concedes that certain coastline infrastructure, such as harbours, require protection. But “ultimately, for most stretches of shoreline, it is far better to just let them recede and to plan for that.”

The coming deluges: More from Matthew McClearn

Matthew McClearn/The Globe and Mail

Climate change threatens Canada’s dams. But who’s keeping track?

For Port of Vancouver, underestimating Pacific sea-level rises could come at a high price

Halifax’s battle of the rising sea: Will the city be ready for future floods and storms?

Why Fort McMurray’s flood defences weren’t ready when the town needed them most

Tuktoyaktuk teetering: Hamlet’s shoreline erosion a warning to rest of Canada’s North

Short on options, Îles-de-la-Madeleine residents make a strategic retreat from rising seas