Nearly one million people in Canada are expected to have dementia by 2030, an increase of more than 65 per cent from 2020, according to the projections of a new report from the Alzheimer Society of Canada.

And unless measures are taken to reduce the risks and delay the onset of the condition, close to 1.4 billion caregiving hours – the equivalent of more than 690,000 full-time jobs – will be required annually to support the 1.7 million Canadians who will have dementia by 2050, the report, published Tuesday, said.

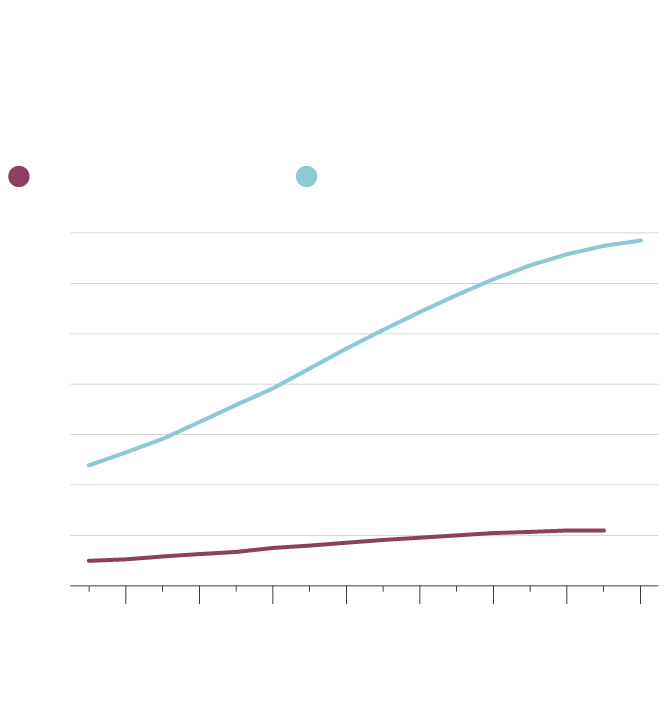

Number of people living with dementia and the number of new cases of dementia per year in Canada, 2020 to 2050

In thousands

New dementia cases

All dementia cases

1,750

1,500

1,250

1,000

750

500

250

0

2020

2030

2040

2050

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ALZHEIMER

SOCIETY OF CANADA

Number of people living with dementia and the number of new cases of dementia per year in Canada, 2020 to 2050

In thousands

New dementia cases

All dementia cases

1,750

1,500

1,250

1,000

750

500

250

0

2022

2026

2030

2034

2038

2042

2046

2050

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ALZHEIMER

SOCIETY OF CANADA

Number of people living with dementia and the number of new cases of dementia per year in Canada, 2020 to 2050

In thousands

New dementia cases

All dementia cases

1,750

1,500

1,250

1,000

750

500

250

0

2022

2026

2030

2034

2038

2042

2046

2050

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: ALZHEIMER SOCIETY OF CANADA

If not much changes to the current trends, the number of people with dementia and the number of people caring for them “is going to be enormous,” said Saskia Sivananthan, chief research officer at the Alzheimer Society of Canada. But this amount of growth is not inevitable, she said. By investing in addressing modifiable risk factors that improve brain health, “as a government and as a country, we can start changing and shifting some of those numbers down.”

The report, titled Navigating the Path Forward for Dementia in Canada, is the first of a series from the organization’s Landmark Study, which uses computer modelling and demographic data from Statistics Canada to forecast the impact of dementia on the country over the next 30 years. Two additional reports, examining the social and economic effects of dementia, will be published in the coming months, the Alzheimer Society of Canada said.

In 2020, an estimated 597,300 people had some form of dementia in Canada, with an incidence rate of 348 new cases diagnosed a day, the report released on Tuesday showed. Common forms of dementia include Alzheimer’s dementia, a later stage of Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia, which occurs from a lack of blood flow to the brain.

There were 350,000 unpaid caregivers for people with dementia, which includes family members, friends and neighbours, in 2020. They provided an average of 26 hours of care each week, totalling 470 million hours of care a year.

Based on current trends, the report said by 2050 both the number of people with dementia and the number of caregivers will nearly triple.

The projections did not account for any potential impact of COVID-19, said Joshua Armstrong, a scientist with the Alzheimer Society of Canada who authored the report. He explained there is a lack of data about how the stresses associated with the pandemic or the virus itself may affect these estimates.

The report, however, showed that improving efforts to reduce the risks and delay the onset of dementia could result in up to millions of fewer cases. If everyone delayed getting dementia by one year, there would be nearly 500,000 fewer new cases by 2050, the projections showed. If everyone delayed getting dementia by 10 years, there would be more than four million fewer new cases by 2050.

Certain risk factors, such as age and genetics, are not modifiable, but the report pointed to various risk factors that are, including lack of education, hearing loss, social isolation, physical inactivity and air pollution. It provided a list of measures people can take, such as being physically and socially active, getting six to eight hours of quality sleep a night, avoiding excessive alcohol use, seeking treatment for depression, avoiding head injuries and using hearing aids, if needed.

Dr. Armstrong emphasized the need for communities, public-health agencies and other governmental organizations to help individuals.

“They’re only modifiable if people have the support and resources to modify them,” he said.

Dr. Sivananthan added it’s important to try to reduce multiple risk factors, since a range of small changes can have a cumulative effect.

The report offered recommendations aimed at organizations, health systems and various levels of government. One is for the federal government to cost out and fully fund the national dementia strategy, a road map that Ottawa released in 2019. Its recommendations for provincial and territorial governments include improving education for all ages and helping workplaces provide flexible support to caregivers.

Roger Wong, a clinical professor in geriatric medicine at the University of British Columbia, said he hopes the report would spur more support for the care of individuals with dementia.

Dr. Wong, who was not involved in the study but chairs the Alzheimer Society of Canada’s research and knowledge committee, also expressed a desire for policy makers to promote research and public education about the issue.

“Now that we know, we have to do something about it,” he said.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.