The Elbow River in Calgary.Jeff McIntosh/The Globe and Mail

When rising waters along the Elbow River forced an evacuation order in and around downtown Calgary eight years ago, Brenda Leeds Binder didn’t think she had much to worry about.

Her home in the city’s Elbow Park neighbourhood wasn’t right along the river, nor was it affected by a significant flood in 2005, before she lived there. She and her husband moved some things off the floor of their basement, expecting a few inches of water at most. They returned several days later to a flooded basement, their coffee table and other belongings floating in five feet of water that had also destroyed appliances and their furnace.

Still, Ms. Leeds Binder considers herself one of the lucky ones. The 2013 flood damaged thousands of homes and businesses, including more than a dozen houses that needed to be demolished completely, and killed one person in Calgary and four others elsewhere in southern Alberta. It was the costliest flood in Canadian history, with the total damage estimated at $5-billion.

The recent flooding and mudslides in British Columbia, which killed at least four people, destroyed sections of highway, and left vital farmland in Abbotsford underwater, are the latest reminder of how bad things can get when built-up areas aren’t adequately protected. The cost of the damage is still being tallied but it is expected to surpass the 2013 Calgary flood.

Calgary’s solution to the problem of rising waters, which are becoming an increasingly urgent issue as a warming climate leads to increased precipitation and flooding: a proposed $432 million reservoir 15 km west of the city that’s designed to take in water when the Elbow River runs high. Known as the Springbank off-stream reservoir, or SR1, it would reduce the peak volumes Calgary would otherwise have to cope with. Construction is to be begin early next year and is expected to take three years.

“This will be one of the most significant structural flood mitigation projects that has been undertaken, certainly in our region, if not our country,” said Frank Frigo, a water resources engineer who leads Calgary’s watershed analysis team. “It’s very important to the protection of communities all along the Elbow River, including the downtown core.”

By and large, only bigger cities like Calgary can afford to defend themselves with infrastructure on this scale. (Alberta will pay most of SR1′s construction costs, while the federal government will contribute $168.5-million through its Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund.) But critics point out that projects like SR1 aren’t foolproof.

While dams may provide a sense of security, they can fail when pushed beyond their limits. They can also enable risky behaviour, such as continued development within known floodplains. Such projects also tend to have far-reaching environmental implications that must be carefully managed. There’s always the risk that engineers rely unduly on historical flooding levels, fighting yesterday’s weather while underestimating the deluges a warming climate might deliver. And they often take longer to build than expected.

The pattern of ignoring low-probability but high-consequence hazards has repeated itself elsewhere in Alberta, with disastrous results. In 2013 the town of High River saw massive flooding that closed roads and forced an evacuation of the area.Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

Alberta’s original plan was to have SR1 fully operational by early 2018. Regulatory delays, opposition from First Nations and landowners, and two changes of government derailed that timeline. The project pitted the interests of the province’s largest city against a vocal group of rural landowners and ranchers, including families who’ve lived there for a century.

Some flood control experts regard SR1 as a high-cost fix made necessary by decades of poor planning decisions, and a tendency to ignore low-probability but high-consequence hazards until it’s too late. That pattern has repeated itself elsewhere in Alberta, including High River and Fort McMurray, with disastrous results. Far better to move people out of floodplains, experts argue, than enter an expensive struggle with Mother Nature that will never end.

But Alberta’s Natural Resources Conservation Board concluded in June that the project was in the public interest, and that its benefits outweigh any environmental impacts, including airborne dust, harm to fish, and the loss of wildlife habitat. The federal Impact Assessment Agency of Canada arrived at essentially the same conclusion in July. And now, the province says it has acquired all of the required land through voluntary agreements with landowners.

For many residents of Calgary’s river communities, SR1′s completion can’t arrive soon enough. Every year that has passed without its added layer of protection has been a source of angst for Ms. Leeds Binder.

“There’s anxiety every single spring,” says Ms. Leeds Binder, who is co-president of the Calgary River Communities Action Group and has been advocating for upstream protection since shortly after the flood.

“I’m not going to kind of breathe that sigh of relief until that project is actually operating.”

The Springbank Reservoir: A massive holding tank

Large portions of downtown Calgary lie in the floodplains

of the Bow and Elbow Rivers. Alberta’s government

plans to build a large reservoir, known as SR1, alongside

the Elbow River which would significantly reduce the

volumes of water passing through Calgary during major

floods. A separate solution will be needed to reduce

flood risk along the Bow.

ALBERTA

Bow River

Calgary

Calgary

Int’l

Airport

Springbank Off-Stream

Reservoir project

Nose

Hill

Park

Elbow River

Calgary

Stampede

100-year

flood zone

Glenmore

Reservoir

Bow River

SR-1 bears similarities with other flood control structures

worldwide, variously known as off-stream reservoirs,

storage reservoirs, detention basins and retarding basins.

Though there appears to be no official list of the largest

such structures, SR1 would store more water than

California’s San Luis Dam, sometimes described as the

U.S.’s largest off-stream reservoir…but is dwarfed by

Japan’s Waterase Retarding Basin

Storage capacity, in millions of cubic metres

1,603.5

384.9

Sites

Reservoir*

Englewood

Dam

Sacramento Valley,

California

Montgomery Co.,

Ohio

200

86.3

Waterase

Retarding Basin

Lockington

Dam

North of Tokyo,

Japan

Shelby Co.,

Ohio

77.8

59.4

Springbank

Reservoir*

San Luis

Dam

Alberta,

Canada

Merced Co.

California

*Proposed

matt mcclearn and john sopinski/the globe and mail

source: alberta transportation qgis; esri

The Springbank Reservoir: A massive holding tank

Large portions of downtown Calgary lie in the floodplains

of the Bow and Elbow Rivers. Alberta’s government

plans to build a large reservoir, known as SR1, alongside

the Elbow River which would significantly reduce the

volumes of water passing through Calgary during major

floods. A separate solution will be needed to reduce

flood risk along the Bow.

ALBERTA

Bow River

Calgary

Calgary

Int’l

Airport

Springbank Off-Stream

Reservoir project

Nose

Hill

Park

Elbow River

Calgary

Stampede

100-year

flood zone

Glenmore

Reservoir

Bow River

SR-1 bears similarities with other flood control structures

worldwide, variously known as off-stream reservoirs,

storage reservoirs, detention basins and retarding basins.

Though there appears to be no official list of the largest

such structures, SR1 would store more water than Califor-

nia’s San Luis Dam, sometimes described as the U.S.’s

largest off-stream reservoir…but is dwarfed by Japan’s

Waterase Retarding Basin

Storage capacity, in millions of cubic metres

1,603.5

384.9

Sites

Reservoir*

Englewood

Dam

Sacramento Valley,

California

Montgomery Co.,

Ohio

200

86.3

Waterase

Retarding Basin

Lockington

Dam

North of Tokyo,

Japan

Shelby Co.,

Ohio

77.8

59.4

Springbank

Reservoir*

San Luis

Dam

Alberta,

Canada

Merced Co.

California

*Proposed

matt mcclearn and john sopinski/the globe and mail

source: alberta transportation qgis; esri

The Springbank Reservoir: A massive holding tank

Large portions of downtown Calgary lie in the floodplains of the Bow and Elbow Rivers. Alber-

ta’s government plans to build a large reservoir, known as SR1, alongside the Elbow River

which would significantly reduce the volumes of water passing through Calgary during major

floods. A separate solution will be needed to reduce flood risk along the Bow.

ALBERTA

Bow River

Calgary

Calgary

Int’l

Airport

Nose

Hill

Park

Springbank Off-Stream

Reservoir project

2

Elbow River

Calgary

Stampede

100-year

flood zone

Glenmore

Reservoir

Bow River

SR-1 bears similarities with other flood control structures worldwide, variously known as off-stream

reservoirs, storage reservoirs, detention basins and retarding basins. Though there appears to be no

official list of the largest such structures, SR1 would store more water than California’s San Luis Dam,

sometimes described as the U.S.’s largest off-stream reservoir…but is dwarfed by Japan’s Waterase

Retarding Basin

Storage capacity, in millions of cubic metres

1,603.5

384.9

200

77.8

86.3

59.4

Sites

Reservoir*

Waterase

Retarding Basin

Lockington

Dam

Englewood

Dam

San Luis

Dam

Springbank

Reservoir*

North of Tokyo,

Japan

Shelby Co.,

Ohio

Sacramento Valley,

California

Montgomery Co.,

Ohio

Alberta,

Canada

Merced Co.

California

*Proposed

matt mcclearn and john sopinski/the globe and mail, source: alberta transportation qgis; esri

Calgary’s extraordinary vulnerability to flooding stems from a long history of building on the floodplains of the Bow and Elbow, the two rivers which meet in the heart of the city. Though many Canadian municipalities made similar choices, Calgary’s peculiar geography ensured that the consequences would be unusually severe.

The Bow and Elbow Rivers originate in the Rocky Mountains, to the west of Calgary, where heavy rains on melting snowpack can cause both rivers to swell quickly. Flooding has been the city’s constant companion, with notable events in 1879, 1897, 1902, 1929, 1932 and 2005. Hydrologists refer to the Elbow as a particularly “flashy” river: The steep mountain terrain to the west means that flooding conditions developing in the mountains arrive in Calgary with little warning.

“That catchment is very close to Calgary and is a fast-responding system,” Mr. Frigo said. “Often if a flood is being forecasted in Winnipeg, there is a lead time of multiple weeks. Whereas here in Calgary, we can go from completely normal summertime conditions to 2013-sized events in nine to 12 hours.”

Like other rivers, the Elbow has changed its route constantly over thousands of years, leaving abandoned channel scrolls known as “paleochannels” that are still found throughout several downtown neighborhoods. During serious floods, the river can overflow into these paleochannels, flooding neighborhoods that might have seemed out of harm’s way.

In apparent disregard for these realities, city officials for many years permitted unfettered construction within floodplains as Calgary grew from a frontier outpost into a major North American city. Gaps in Alberta’s approach to flood mitigation made that possible. A 2015 report by the province’s Auditor General noted that municipalities “have not been required to deal with flood hazard in their land use by-law.” Some municipalities restricted floodplain development, while others did not. Calgary largely fell in the latter category; a municipal report noted that while some restrictions on floodway development were introduced in 1985, “at times these limitations are relaxed for development.”

The 2013 flood exposed the cost of those decisions. In response, the province considered a wide variety of options for protecting Calgary. At first, officials embraced principles that are popular among flood resilience experts. In a 2014 report, for instance, they recognized that “sometimes it’s more practical to keep people away from water, rather than trying to keep water away from people.”

In 2014, the provincial government began exploring a Dutch approach to managing floods along branches of the Rhine River, known as Room for the River. Put simply, this approach involves removing dikes and restoring landscapes along rivers so that they can accommodate and store floodwaters when the river spills over its banks. A subsequent report by WaterSmart, a water management consultancy, informed Albertans that the Dutch had learned several lessons during floods in the 1990s, one of which was that “rivers are powerful; it is best to rely as little as possible on infrastructure that can fail.” While the report explored temporary storage as a potential solution, it also urged the province to consider relocating people from high-risk areas.

Relocation is just one of a large number of “non-structural” measures that have gained popularity (at least among flood mitigation experts) during the last two decades. Others include restricting development in flood risk areas, for example by imposing mandatory setback distances from waterways, or banning homebuilding entirely in high-risk areas. Part of their attraction is that they’re typically far less expensive than erecting large structural defences — provided that they’re adopted early enough.

Calgary faced a city-wide state of emergency in June 2013 after the Elbow River crested, causing as many as 100,000 people to evacuate.Chris Bolin/The Globe and Mail

Moving people out of harm’s way after decades of poor planning decisions, on the other hand, is expensive and politically fraught. In Calgary, it was a complete non-starter: A 2014 municipal report discouraged that option except in the most vulnerable areas, while barely bothering to provide a justification. It came down to money: The city has estimated that it would cost more than $2-billion to buy out all properties at risk of flooding. Alberta Transportation documents estimated that removing homes, businesses, roads and other vulnerable infrastructure “could cost total in the tens of billions of dollars.”

Within a year, officials settled on SR1 as the way forward. Instead of leaving room for the Elbow River, Alberta would tame it once and for all.

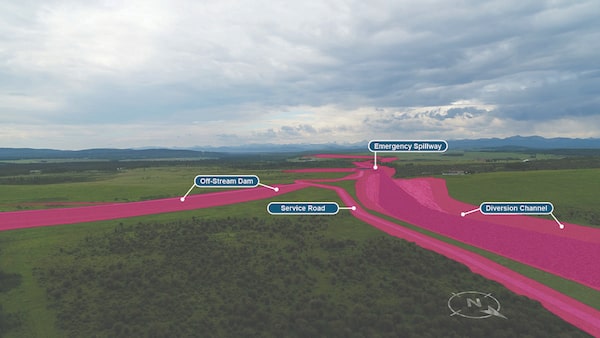

Think of SR1 as a giant holding tank for floodwaters.

When the Elbow River runs high, a portion of its flow would be diverted — at up to 600 cubic meters per second – through a diversion channel into the reservoir. This would reduce peak flows entering the Glenmore Reservoir, 18 kilometres downstream in Calgary, and reduce the risk of flooding within the city itself. When full, the reservoir would be 25 meters deep — at which point the diversion gates would close.

Matthew Hebert, executive director of transportation policy with Alberta Transportation, estimated that based on historical records of Elbow River flooding, the project would likely operate about once a decade. Once the river’s flow returns to normal, the stored water would be gradually released back into the Elbow River over a month or two. At all other times, the reservoir would be empty.

A rendering of Springbank's diversion structure on the Elbow River, looking north.Supplied

SR1 would be massive in almost every dimension. Its $432-million budget is up from an earlier estimate of $297 million. It would require 1,439 hectares currently occupied by ranches and farms, summer camps and some residences. When filled, it would hold a maximum of 78 million cubic meters, equivalent to more than 31,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The project is designed to handle flooding on the scale of what happened in 2013, which on the Elbow River was deemed to be a 1-in-200 year event. (Compare that with Winnipeg’s Red River Floodway, a 47-kilometre channel designed to allow floodwaters to bypass the city. It’s rated to handle up to a 1-in-700 year flood.) That level of protection is necessary, Mr. Frigo said, because the warming climate is expected to increase flows during major events by about 20 per cent over the course of this century.

SR1′s scale also means there will be significant environmental consequences requiring careful management. The Elbow is a silty river: once the reservoir is drained, it would be coated with silt that could be blown throughout the region. (Plants and chemicals known as tackifiers can be used to bind soil together, reducing wind erosion and suppressing dust.) During operations the reservoir and diversion channel would become death traps for fish; the NRCB was satisfied with Alberta Transportation’s proposed measures, which include a “robust fish rescue program.” Floodwater storage at SR1 would also displace other wildlife, although the NRCB concluded that habitat loss would be negligible “at the regional level.”

A report published in 2020 by the Geneva Association, an insurance industry think tank, noted Canada’s tendency to spend most of its flood-related funding on erecting structural defences and rebuilding after floods, leaving little money for other measures such as buyouts or protecting individual properties. This preference, the report concluded, “continues to be a barrier to more substantial reform.”

It’s also a recipe for delays. A review by Martin Ignasiak, a regulatory lawyer with Osler, released in 2020 attributed those delays to deficiencies in Alberta Transportation’s initial environmental impact statement: the province had been warned it would likely be rejected, he concluded, but it was submitted nonetheless. More delays resulted from responding to the “unprecedented” large number of information requests from provincial regulators.

Delays introduce the risk that another flood might catch Calgary unprepared, which is what happened in Fort McMurray, where delays in completing a network of berms left the community undefended during an ice jam flood in 2020. After 2013, Calgary undertook more than a dozen initiatives to protect itself, such as expanding the capacity of the Glenmore Reservoir and building flood barriers in vulnerable neighborhoods.

Some critics cast SR1 as an unprecedented gamble, but the underlying concept is hardly new. Tetsuya Sumi, an engineering professor at Kyoto University, has visited and written about flood control structures worldwide. He said an ancestor of the concept was born in 1913 when Dayton, Ohio flooded, killing 360; formed shortly afterward, local authorities built five structures known as “dry dams” that still operate today.

An annotated rendering of Springbank's diversion inlet on the Elbow River, looking south.Supplied

Since then, Dr. Sumi said, many flood retention reservoirs similar to SR1 have been set up alongside river channels across Europe and Japan. Off-stream reservoirs have environmental advantages as compared to traditional dams: In particular, they disrupt river ecosystems less because they don’t block the river channel.

But critics regard SR1 as a waste of space. In Japan, off-stream reservoirs are often used as rice paddies when not storing floodwaters. The Waterase Retarding Basin outside Tokyo is used as a natural reserve and recreation area most of the time. SR1′s footprint, by contrast, would be off limits to pretty much everybody during flooding season (May to July). According to the draft land use plan, at other times it would be available to First Nations exercising treaty rights. It could also be used for animal grazing and hiking.

Future Calgarians may also look back on SR1 as a missed opportunity because it doesn’t address the threat of drought. When Alberta began exploring options to protect a repeat of the Calgary flood, several critics urged it to address the two problems simultaneously. But Mr. Frigo said the Elbow River’s small size and poor water quality render it unsuitable for drought mitigation.

SR1 won’t solve all of Calgary’s flooding problems, either, because the city will remain exposed to flooding from the Bow River. City officials estimate that measures undertaken since 2013 have reduced flood risks by about half; Springbank will increase that to about 70 per cent. Other options are under consideration to tame the Bow, such as building large reservoirs, but officials have said that they’re a decade or more away.

The Springbank project was controversial almost as soon as it was proposed, as landowners whose properties sit in the reservoir’s footprint objected to being forced off their land, either by having the provincial government buy them out or, if they couldn’t reach a deal, force a sale through expropriation. The reservoir, which has been overseen by three different provincial governments, became an issue in the 2019 provincial election.

The United Conservative Party had previously suggested the project would be cancelled but eventually came on board over the objection of a small but vocal group of ranchers and landowners.

One of the most vocal opponents, Mary Robinson, is a rancher whose land, where her family has worked since 1888, would be submerged. She has long argued that the reservoir would destroy land with rich heritage value and has blamed “a small number of wealthy individuals” in Calgary for pushing it forward.

Opponents also complained that the province failed to fully consider alternatives, namely a proposed dam and permanent reservoir at McLean Creek, farther upstream. They argued a dam at McLean Creek would affect fewer landowners, protect more communities, including Bragg Creek and Springbank, and leave a reservoir that could be used for canoeing and kayaking.

Karin Hunter of the Springbank Community Association, argued that once politicians settled on the SR1 project, they weren’t interested in considering anything else.

“It got spun very early on as just a few landowners holding up flood mitigation for a million people.

Fifth-generation rancher Mary Robinson is concerned about what will happen to her land, located along the Elbow river, if the Springbank Dam goes ahead.Leah Hennel/The Globe and Mail

And therein lies the rub: SR1 will disrupt the lives of those living in its sizeable footprint so that life for Calgarians can proceed largely as usual. Twyla Kowalcyz, a climate resilience specialist with Associated Engineering Ltd., said Springbank will greatly improve Calgary’s flooding protection. But she noted that even in neighborhoods highly vulnerable to flooding, few residents accepted voluntary buyouts when they were offered. As a result, affluent neighborhoods along the Elbow River look much as they did before 2013.

“A lot of those houses go right onto the river,” she said. “So even there, the landscape along the Elbow within the city hasn’t really changed.”

Calgary Councillor Gian-Carlo Carra, whose ward includes the Inglewood neighbourhood east of downtown, has little sympathy for rural landowners. He said they’ve been “well compensated” and he blamed them for delaying the project. He said their needs can’t outweigh Calgary’s.

“We’re talking about grazing land for a couple of ranching families. A hundred years ago [when some of those families purchased the land], we didn’t need any of this stuff. There wasn’t a city of 1.4 million people that’s an economic engine of our country.”

The Tsuut’ina Nation dropped its objections last year after the provincial government agreed to fund $32-million in flood mitigation projects. Rocky View County formally dropped its opposition last year, in exchange for $10-million and a promise to prioritize other infrastructure projects in the area.

The Alberta government announced in early November that it had reached agreements with landowners to purchase all required land without resorting to expropriation — a particularly fraught option for a government that has promised to strengthen landowners’ rights. Construction is now set to begin next year.

Transportation Minister Rajan Sawhney acknowledged that negotiations with landowners were contentious, but she said the province needs to ensure the devastating flooding isn’t repeated.

“It was never an easy conversation,” she said in an interview. “There’s a lot of history behind it. There’s a lot of emotion behind this, as well. But ultimately there was $5-billion in damage in the 2013 floods and people lost their lives.”

Interested in more stories about climate change? Sign up for the Globe Climate newsletter and read more from our series on climate change innovation and adaption.