Dr. Brooks Fallis, an outspoken critic of the Ford government's pandemic response, on May 30. When Dr. Fallis relied on the Freedom of Information Act to learn more about his termination from his position at William Osler Health System, he was met with pages of blacked out documents, as well as opposition from a Bay Street law firm.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Brooks Fallis was the interim medical director of critical care at William Osler Health System when the pandemic’s vicious second wave began hammering his hospital’s intensive care unit. Frustrated with the provincial government’s handling of the crisis, he began speaking out publicly – first on Twitter, then in the media.

And then, in January, 2021, he was abruptly terminated from his position at the Greater Toronto Area hospital network. Dr. Fallis says he was told by William Osler executives that the decision had nothing to do with his medical performance.

Rather, Dr. Fallis says, he was told the reason was his public criticism of the Ontario government, which executives believed was putting the hospital’s funding at risk, as well as his failure to always warn the hospital’s media relations team about his appearances in the press.

Dr. Fallis had questions about the lead-up to his termination, and about what pressure, if any, had been placed on the hospital to silence him. Frustrated with the answers he was receiving from his employer, he began filing requests under freedom of information (FOI) legislation, which requires public institutions, including hospitals, to release records to people who ask for them.

The physician’s experience, and his willingness to fight for information, provides a striking example of the arbitrary standards public institutions apply when deciding what to release, as well as the measures they will take to avoid disclosing information, including hiring expensive lawyers.

From overused redactions, to lengthy delays, to record searches that came back incomplete, Dr. Fallis’s case showcases some of the most common problems that The Globe and Mail uncovered as part of Secret Canada, its investigation into Canada’s broken access regime. The project found that, across the country, public bodies are breaking FOI laws, which exist to hold governments accountable.

Dr. Fallis’s FOI saga, which has stretched all the way to Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s office, has lasted more than two years. During that time, disheartened with replies he has received from the hospital, he has filed multiple appeals with Ontario’s Information and Privacy Commissioner.

At times, the mere act of filing an appeal has prompted the hospital to speed up its replies, locate more records and remove redactions.

“Every time I pushed back, I got more information. It doesn’t leave you with a lot of confidence,” Dr. Fallis said in a recent interview.

William Osler hired a Bay Street law firm, Borden Ladner Gervais, to deal with Dr. Fallis’s requests for information. (It is common for public institutions to hire outside law firms to challenge civilian information appeals.)

Through an FOI request, Dr. Fallis learned that William Osler had paid the firm $132,092.46 to consult on FOI work between March 1, 2021, and March 31, 2022. This represents all work BLG did during that period for the hospital on FOI-related matters, not necessarily only on Dr. Fallis’s case. (It’s not possible to obtain information on billings connected to one specific file through an FOI request, because that information is protected by solicitor-client privilege.)

“There’s two things. ... I’m up against a nearly billion-dollar organization, which is now hiring a high-profile law firm to do everything it can to redact as much information as possible,” Dr. Fallis said. “The second thing, you want to talk about waste in the health care system? This is $130,000 of money that could have been spent on health care.”

In a statement, William Osler said it – “like all hospitals” – works with external lawyers. “The stated monetary amount is not material to this FOI process,” public relations director Emma Murphy wrote.

This story began in September, 2020, six months into the pandemic. Earlier in the year, Dr. Fallis had accepted a one-year contract to serve as interim medical director and division head of critical care.

With case counts climbing, he believed the public needed to know that – in his view – the provincial government was doing a poor job of handling the crisis.

He spoke out on Twitter against Mr. Ford’s back-to-school plan, and the secrecy around the government’s expert command table. “Ontario is suffering a crisis of COVID-19 leadership. Science and transparency are sorely lacking in @fordnation‘s response and changes are urgently needed,” he wrote in one tweet.

These comments caught the attention of the media, and soon Dr. Fallis became a sought-after guest and commentator. As his profile grew, he said, he was cautioned by hospital leadership to make clear he was speaking on his own behalf, not William Osler’s.

According to Dr. Fallis, William Osler’s chief of staff at the time, Frank Martino, told him that Mr. Ford had personally phoned the hospital’s chief executive officer to complain about Dr. Fallis’s criticism. The Premier’s office has denied this call occurred.

In a subsequent conversation with Naveed Mohammad, who was William Osler’s CEO at the time, Dr. Fallis says he was warned that there were concerns that the provincial government might withhold funding because of the bad press.

Still, Dr. Fallis felt he had support from William Osler’s leadership to continue speaking out, as long as he agreed to give the hospital a heads-up before media appearances, and to be cautious about how he was representing himself.

But then, in January, 2021, Dr. Fallis was told his contract was done and not being renewed. Livid, he went public in The Globe. He told a reporter at the time: “I really believe that what happened here was wrong. … It sends the message to others, if they speak up, there will be consequences.”

The Premier’s office and William Osler both released statements denying that government officials had pressed the hospital not to extend Dr. Fallis’s contract.

But that didn’t placate Dr. Fallis.

In March, 2021, he filed an FOI request with the hospital for copies of any communications between senior hospital officials and politicians or their representatives concerning him or his contract renewal. The hospital said it would need until the end of the year to respond. (In Ontario, public institutions are supposed to provide records within 30 days, except in specific situations that would warrant extensions.)

Dr. Fallis appealed this delay, and William Osler supplied a 175-page package in September. In total, 41 per cent of the pages had some information redacted.

Every province and territory in Canada, as well as the federal government, has its own freedom of information law. While there are differences between jurisdictions, there is a universal principle that information held by public institutions is supposed to be public, except in some specific circumstances. This is why each law includes exemptions to access for sensitive information, such as business trade secrets, or records whose release would threaten national security. These exemptions are supposed to be applied sparingly.

Dr. Fallis had doubts about William Osler’s redactions.

In a letter accompanying the release package, the hospital wrote that some information was being withheld either because the records were “not responsive” to Dr. Fallis’s request, or because they fell under exemptions that protect “advice and recommendations,” solicitor-client privilege and “personal privacy.”

Sometimes the blacked-out sections were small – a name, or e-mail address – but others covered paragraphs of text.

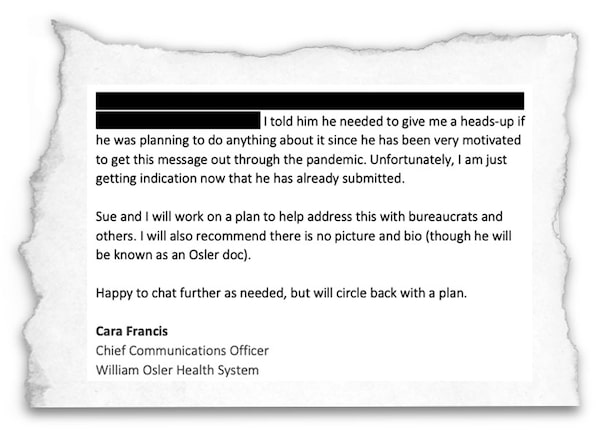

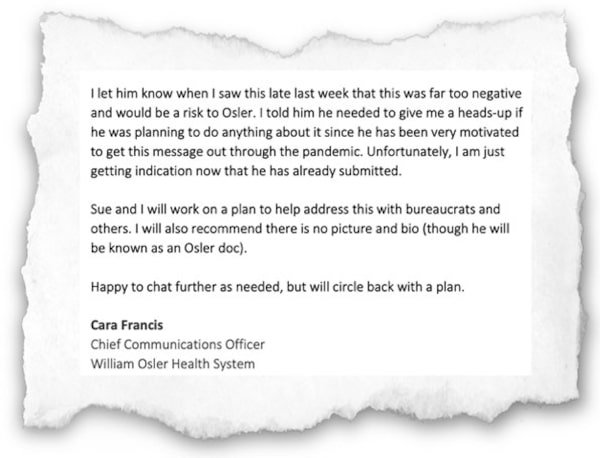

For example, in one e-mail, William Osler’s chief communications officer, Cara Francis, was writing to senior leadership about an opinion piece that Dr. Fallis had written, entitled “Less Politics, More Science.” He had forwarded a draft to the hospital’s communications team.

In the version of the e-mail provided to Dr. Fallis, a sentence was redacted. In the next sentence, Ms. Francis wrote, “I told him he needed to give me a heads-up if he was planning to do anything about it since he has been very motivated to get this message out through the pandemic.”

The documents provided to Dr. Fallis included partly redacted e-mails from Cara Francis, chief communications officer at William Osler.Illustrations by The Globe and Mail

Dr. Fallis filed another appeal, this time targeting the redactions. Again, William Osler agreed to take a second look at what had been withheld.

In February, 2022 – one year into his hunt for answers – he received a revised package with half of the redactions removed.

Dr. Fallis couldn’t understand why some of the newly unearthed passages had been blacked out in the first place, such as a conversation between executives about him appearing on CBC’s Metro Morning to discuss ICU capacity.

Emboldened, Dr. Fallis pushed back harder. Once again, the hospital agreed to go back and reconsider. This time, William Osler removed even more of the redactions and located additional records.

On this third pass, Dr. Fallis felt he was finally getting somewhere. The new package revealed the missing sentence from the “Less Politics, More Science” e-mail chain. It said, “I let him know when I saw this late last week that this was far too negative and would be a risk to Osler.”

And among the records William Osler had newly discovered was an “issues management plan” to deal with any fallout from Dr. Fallis’s criticism of the province. Part of the strategy was to “ensure advance notice with relevant elected officials” and “mitigate potential for adverse reputational and relationship impacts on Osler.”

Both of these records spoke directly to Dr. Fallis’s allegations against William Osler.

“What reason did they have to redact this information? They did it because it made them look bad,” Dr. Fallis said.

When asked to comment on why information had initially been redacted, then later released, William Osler’s Ms. Murphy said in a statement that the hospital works closely with legal and privacy experts to ensure it is in compliance with access laws and regulations.

“The FOI legislation and FOI information request process allows the information custodian a degree of discretion in the release of information, hence the inclusion of the appeal process,” she wrote.

Dr. Fallis said filing, managing and appealing these FOI requests has been like a second job for him. (He continues to practise as an intensive care doctor in Toronto.) He has also filed requests with Ontario’s Cabinet Office, for Mr. Ford’s cellphone records. He wants to see if the Premier made any calls to hospital executives in November, 2020, or in the weeks around his termination in early 2021.

In response, he was told the Premier’s phone showed no incoming or outgoing calls during those time periods.

“I am struggling to believe that,” Dr. Fallis said.

In an e-mail to The Globe, Caitlin Clark, a spokesperson for Mr. Ford, said that if an FOI requester asks for information that does not exist, they will be told as much in the reply. “An individual’s assumptions about what he or she thinks exists does not equate to records being in existence. As always, our office complies with all applicable legislation as set out in the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act,” she said.

More on The Decibel

Reporters Robyn Doolittle and Tom Cardoso tell The Globe and Mail’s news podcast about Canada’s broken freedom of information system, and how they spent more than a year and a half investigating its failures. Subscribe for more episodes.