British-born bestselling crime writer Peter Robinson was a writer's writer, who was admired by others who made a living writing mystery novels.J.P. MOCZULSKI/Reuters

British-Canadian novelist Peter Robinson was part of a talented wave of Canadian crime-fiction writers, along with Louise Penny and others, who have achieved popular success while also garnering critical acclaim.

Mr. Robinson lived in Toronto, but Alan Banks, the protagonist in 28 – soon to be 29 – of his crime novels, lived in the fictional town of Eastvale in Yorkshire, England. His books were regularly on Britain’s Sunday Times bestseller lists, and his Alan Banks novels were adapted into the British crime television series DCI Banks, which ran from 2010 to 2016.

The author, who died of cancer in Toronto on Oct. 4 at the age of 72, also wrote novellas, short stories and poetry. Over 35 years, the author found a receptive audience for his Alan Banks books, selling a remarkable 8.75 million books through his UK publishers Hodder & Stoughton and Pan Macmillan, as well as “many hundreds of thousands” in Canada, according to Jared Bland, the outgoing president of McClelland and Stewart. His books were also translated into 20 languages.

He was a writer’s writer and was admired by others who made a living writing mystery novels.

“Peter was part of the renaissance of crime writing not only in Canada but worldwide. It has become complex, multi-layered looking at different themes,” said bestselling crime writer Louise Penny, who was Mr. Robinson’s friend. “His books aren’t necessarily like mine; they are proudly mysteries and crime novels, but they’re not really about the crime, they’re about the human beings involved. That’s why people are drawn to them and drawn to Alan Banks. He has made them deeply human and recognizable, and I think that has helped to bring crime novels and crime writing to the fore. Not ghettoized and not genre-driven and not formulaic.”

Mr. Robinson, who had a PhD in literature, was known for pushing against the constraints of the often-formulaic genre. “I’m more interested in character,” he told The Globe’s Sandra Martin in 2001. “I’m more interested in society, what’s happening in the world, rather than in a puzzle. I don’t really care about the little bit of obscure cigarette ash, and I don’t think a lot of writers do these days.”

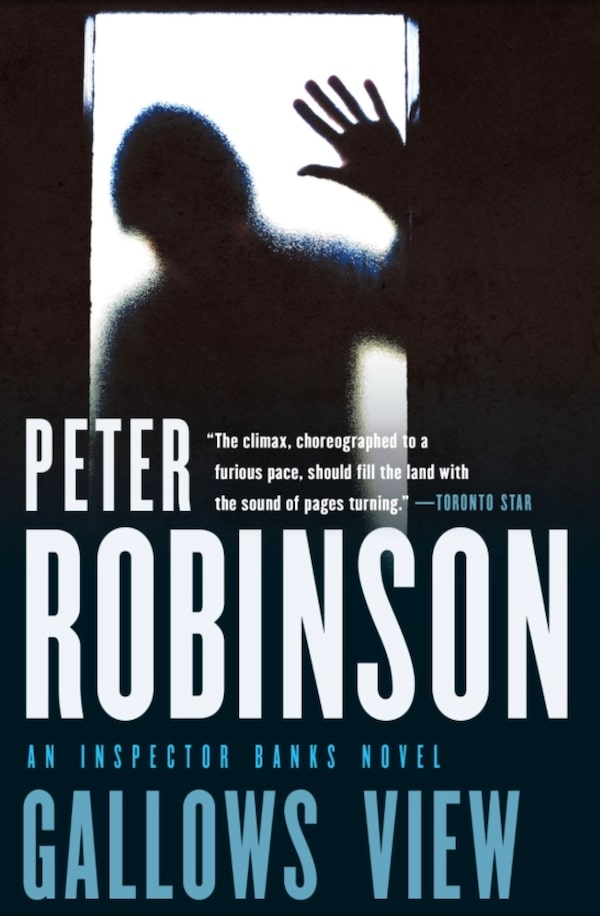

His Alan Banks novels won prestigious prizes in Canada, the United States, Sweden, Finland, France and his native Britain. Crime Writers of Canada gave him an armful of Arthur Ellis Awards over the years, along with a Derrick Murdoch Award in 2010 for his contributions to the genre and a Grand Master Award in 2020 to honour his substantial body of work and national and international recognition. He also won France’s Grand Prix de Littérature Policière and Sweden’s Martin Beck Award. His first novel, Gallows View, was shortlisted for the UK Crimewriters’ Association’s John Creasey Award.

Peter Robinson was born in Leeds, England, on March 17, 1950. His family was solidly working class: His father, Clifford, worked in a local factory, Yorkshire Imperial Metals; his mother, Miriam Jarvis, was a cleaner. The family lived in public housing, called a Council Flat in England. Peter qualified to go to West Leeds Grammar School, a state-run school leading to university. His background was much like that of his main character, Alan Banks, who in one novel described himself as “… a working-class boy from Peterborough” whose father was a sheet-metal worker.

Alan Banks was fictional but: “Peter always infused the character with his own passions,” Mr. Bland said.

Like Mr. Robinson in real life, the fictional Alan Banks made it into a grammar school.

“In his own education, he had been very lucky indeed,” Mr. Robinson wrote of his detective’s school days. He then described in some detail the cruel class system that separates clever boys from their friends with the “11-plus” exam that decides who goes to university and who will “… be moulded into an ideal electrician, brick-layer or road sweeper.”

Despite their similarities, Mr. Robinson made a point of differentiating his Banks character from himself in certain ways, including appearance: Banks was short and dark-haired, whereas his creator was six feet tall and blond.

“We are very different,” Mr. Robinson told The Globe. “I don’t think I could do his job and he probably couldn’t do mine.

“We probably shared very similar childhoods and adolescences and when we hit the age of about 18, we went in different directions. I went into literature and the arts and he went on a course that took him toward the police as a career. So our paths diverged and have run in parallel universes ever since.”

After grammar school, Mr. Robinson enrolled in a part-time business course while working in the office at the firm where his father worked. Business wasn’t for him, and he quit and knocked about in Amsterdam for a while. He then took a degree in English at the University of Leeds and, while there, saw an advertisement for a course in creative writing at the University of Windsor and moved to Canada.

At the University of Windsor, his tutor was the great American writer Joyce Carol Oates. He then earned a PhD in English at York University. During his studies he supported himself working as a university teaching assistant and as an English teacher at community colleges. Mr. Robinson was writer-in-residence at the University of Windsor in 1992-93, and after that, he took up writing full-time, teaching occasional short courses at the University of Toronto.

Many people take creative writing courses; few become as successful as Peter Robinson. He published his first mystery novel, Gallows View, in 1987, featuring Detective Chief Inspector Alan Banks.

Though he lived in Canada, he wrote about what he knew best: Yorkshire.

Mr. Robinson kept his English accent, but his accent changed over his lifetime.

“When Peter was growing up, he had a broad Yorkshire accent. It softened a bit when he was at university, but the local accent would come back when we went to stay at our place in Yorkshire,” his wife, Sheila Halladay, said.

The couple owned a house in Richmond, North Yorkshire. It was the town Mr. Robinson used as the model for his fictional town of Eastvale, where Inspector Banks worked. It is in the same sort of area as depicted in the television series All Creatures Great and Small.

“Eastvale is modelled on North Yorkshire towns such as Ripon and Richmond, with cobbled market squares, rather than the kind with one main high street, like Northallerton or Thirsk,” Mr. Robinson wrote in an online question and answer session about his work. “I had to make it much larger than those towns, of course, otherwise, who would believe there could be that many murders? I’ve probably killed the population of the Yorkshire Dales three times over as it is.”

When he and his wife visited North Yorkshire, Mr. Robinson liked to meet people and sit in pubs, listening to conversations, making sure he had the tone of his characters right. During the three and a half decades that he wrote the Banks series, vocabulary and habits evolved. For example, in his first novel Inspector Banks listens to music on a Walkman. There are readers of his latest novels who might not know what a Walkman is. The Yorkshire copper also gets promotions as the novels progress, and by the last book, he is a Detective Superintendent.

Mr. Robinson did update his books if they were reissued. In one novel, A Dedicated Man, published in 1988, he used the names of movie stars Gwyneth Paltrow and Kate Winslet in the updated version. A reader asked him, since the two women were not famous at the time, how did he see into the future?

“I’d like to say I was being prescient, but the truth is a lot more prosaic. For some reason, I had to go through the manuscript again some years ago, and I thought it would be a good idea to update the girl’s screen heroines, as Jessica Lange and Kathleen Turner, who were in the original book, were no longer top stars. I never even imagined someone would be fastidious enough to check it against publication date,” he wrote back to the eagle-eyed reader.

Like many writers, Mr. Robinson didn’t touch type but used four fingers. From the start, he used a computer and ran through a series of them. He liked technology and was an early adopter.

“He was very disciplined. He started writing around 10 in the morning. If it was going well, he would continue in the afternoon; if not, he would go to the pub for a while,” his wife said. His favourite pub was The Feathers, near where he lived in Toronto. “On the average, he published a book a year. Some novels, such as The Summer That Never Was and Before the Poison, were a bit more complicated, involving multiple plots, in different time periods, and took a bit longer.”

His 29th Alan Banks novel, Standing in the Shadows, will be published in the spring. “Peter always took his book titles from popular music. His last book, Not Dark Yet, was from Bob Dylan,” Mr. Bland said. “When a new manuscript came in it was fun to see what music Peter was listening to. He had wide-ranging taste in music. Banks loves music, travel, food, poetry and his family. In these senses he shared much with his creator.”

Along with his literary awards Mr. Robinson was also granted honorary doctorates from the University of Leeds and the University of Windsor.

Mr. Robinson leaves his wife, Ms. Halladay; stepson, Brian Budd; granddaughter, Michaela Budd; sister, Elaine Stead; stepmother, Averil Robinson; and many other relatives in Canada and Britain.

“Peter wrote about the darkest of things,” Mr. Bland said, “but never without the light of hope on the horizon, and always with a finely attuned sense of the fragility and beauty of the human experience.”