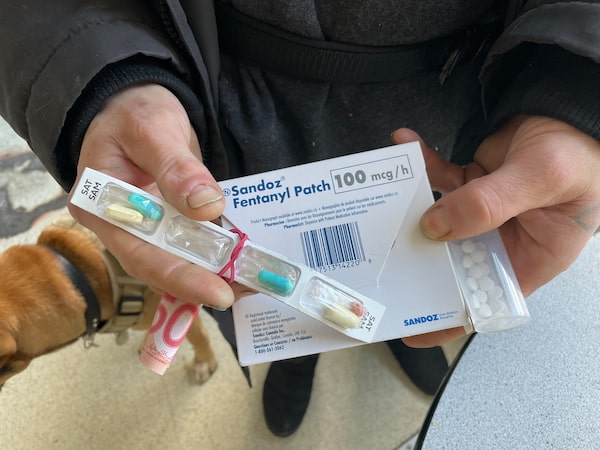

A patient displays medications and a $50 cash kickback that a pharmacy employee delivered to him, in violation of College of Pharmacists of B.C. bylaws, on Feb. 6, in Vancouver. The man tells The Globe and Mail that the pharmacy pays him $50 per week and does not change his fentanyl patches, as ordered by his doctor.Andrea Woo/The Globe and Mail

The BC Pharmacy Association is calling on the province and the profession’s regulatory body to investigate problem pharmacies amid allegations that dozens of locations are offering vulnerable patients prohibited cash incentives for their prescription business.

Mike Huitema, president of the association, which represents thousands of pharmacists in the province, said he is aware of recent, informal discussions among the organization, the Health Ministry and the College of Pharmacists of BC about a number of bad actors in the industry. The association, he said, has urged the ministry and the college to take action.

“We have zero tolerance for this; we do not support these kinds of practices,” he said in an interview. “We hope that the ministry and the college can do something relatively quickly.”

The advocacy organization represents more than 4,000 community pharmacists and pharmacies in B.C.

A Globe and Mail investigation found that a number of pharmacies are exploiting B.C.’s PharmaCare program by targeting economically vulnerable patients – largely those with substance use disorders – with cash incentives to fill their prescriptions at their locations and recruit others to do the same. This maximizes the amounts that the pharmacies can bill the publicly funded drug plan.

Pharmacies charge a dispensing fee for each prescription, and these fees make up a significant portion of their overall revenue. For a patient on income assistance or with First Nations health benefits, a pharmacy that is enrolled with PharmaCare can bill the publicly funded program for up to $10, for each of up to three medications. If one of those medications is methadone, the most commonly prescribed medication for opioid use disorder, the pharmacy can bill another “interaction fee” of $7.70.

This means that a single patient could bring in up to $13,760 a year in pharmacy fees. A pharmacy with a few hundred such patients can bill PharmaCare for millions of dollars a year.

Several patients who have received these alleged kickbacks, which are in violation of college bylaws, have told The Globe that they are usually paid $50 per week to fill at least three prescriptions.

The Globe spoke to 28 doctors, nurses, pharmacists, patients and social-service providers to learn the scope of the practice and how such pharmacies covertly encourage patients to participate. Among them, two doctors, two pharmacists and several patients independently revealed the names of dozens of pharmacies alleged to offer kickbacks, including locations in Vancouver, Burnaby, Surrey, New Westminster and Victoria.

In The Globe story earlier this week, it did not identify many of the sources, including doctors and pharmacists who said they were worried about professional repercussions, and patients who were concerned that they would lose access to medications.

Both the ministry and college issued statements that included identical language saying they could not comment on “complaints that may or may not have been received, or investigations that may or may not be under way currently” unless there was “significant risk of harm to the public or a group of people that would justify such public disclosure.”

At an unrelated news conference on Thursday, Health Minister Adrian Dix reiterated that he could not comment on whether an investigation is under way, but said “rules are there to be upheld, and they will be upheld in B.C.”

“I can assure you that if people think that practices that are unacceptable will be allowed, then they are sorely mistaken,” he said.

The College of Pharmacists of BC did not answer specific questions from The Globe on Wednesday and Thursday, and declined requests to speak with registrar and chief executive Suzanne Solven. The statement from the regulatory body said it “has a long-standing concern about the negative effects of incentive programs in the practise of pharmacy.”

The alleged kickback scheme goes beyond offering patients cash for prescriptions they normally would have received. Some patients and doctors have told The Globe that pharmacists have counselled patients on which medications to ask for, such as those for pain or insomnia – self-reported conditions that don’t require corroborative objective evidence.

A 2015 crackdown focused on methadone claims led to dozens of Lower Mainland pharmacies either shuttering or being forced to withdraw as PharmaCare providers, meaning they could no longer bill the province for various services.

No pharmacies have lost their PharmaCare billing rights since 2019 for providing incentives, according to the Ministry of Health.

Mr. Huitema said that while he could not provide details of meetings because of confidentiality reasons, the ministry is aware of a “handful” of problem pharmacies and his association has pushed government “to do whatever they need to do to get rid of it.”

“I’ve seen pharmacists have their licence suspended for a lot less than that,” he said. “So I mean, there needs to be some punishment with some real teeth.”