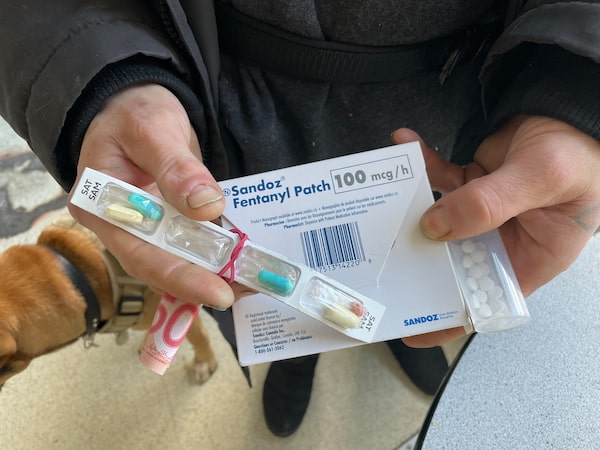

A patient displays medications and a $50 cash kickback that a pharmacy employee delivered to him, in violation of College of Pharmacists of B.C. bylaws, on Feb. 6, in Vancouver. The man tells The Globe and Mail that the pharmacy pays him $50 per week and does not change his fentanyl patches, as ordered by his doctor.Andrea Woo/The Globe and Mail

British Columbia’s Health Ministry sent a letter to pharmacies in the Vancouver region in response to allegations that some pharmacists are providing cash incentives to patients receiving addiction treatment, warning them such inducements are illegal and could trigger fines of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The letter appears to have prompted some pharmacies to stop providing incentives to patients. At a meeting of the BC Association of People on Opiate Maintenance (BCAPOM) on Wednesday in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, seven of 24 members of the advocacy group said their pharmacists had cut off their payments this week.

The Globe and Mail reported in March that dozens of B.C. pharmacies are accused of participating in the kickback scheme, which maximizes the amounts they can bill the province’s publicly funded drug plan.

On May 23, Mitch Moneo, assistant deputy minister of the pharmaceutical, laboratory and blood services division at the Ministry of Health, wrote to pharmacies in the Lower Mainland that provide treatment for opioid use disorder, warning of the penalties.

“I write because the Ministry of Health is deeply concerned about recent reports that some community pharmacies located in the greater Vancouver area are providing cash to people to use their pharmacy, including to receive opioid use disorder treatment – particularly in the Downtown Eastside,” Mr. Moneo wrote.

“It is an offence under Section 51 of the Pharmaceutical Services Act to offer an incentive as an inducement for a beneficiary to receive a benefit from a particular provider. A person who commits such an offence is liable on conviction to a fine of up to $200,000 and/or six months imprisonment.”

Other consequences include administrative penalties of up to $50,000 and the cancellation of a pharmacy’s enrolment in Pharmacare, the public drug plan, Mr. Moneo wrote.

The letter concluded by saying that the ministry’s Special Investigation Unit conducts criminal and regulatory investigations and that the Pharmacare audit team probes pharmacies for compliance.

Pharmacies charge a dispensing fee for each prescription, and these fees make up a significant portion of their overall revenue. For patients on income assistance or with First Nations health benefits, a pharmacy enrolled with Pharmacare can bill the publicly funded program for up to $10 for each of up to three medications, per patient, per day.

For methadone, the most commonly prescribed medication for opioid use disorder, the program also pays pharmacies an “interaction fee” of $7.70, on top of the dispensing fee, for the pharmacist to witness the patient ingesting it. This means a single methadone patient could bring in up to $13,760 a year in pharmacy fees for multiple medications. A pharmacy with a few hundred such patients can easily bill Pharmacare for millions of dollars a year.

The pharmacies appear to target economically vulnerable patients – largely those with substance use disorders – and are accused of putting their health at risk. Some patients have reported that pharmacists will counsel them on which medications to ask for to maximize the number dispensed daily and the resulting billable fees; others say they have medications marked as dispensed despite never having received them.

A 54-year-old woman who had been receiving $160 a month from her pharmacy told The Globe she was cut off from the illegal payments on Monday. The pharmacist referenced the letter, saying she had just started a family and could not risk the penalties, the patient said.

The patient said she is on disability assistance and that extra cash meant the difference between a fridge filled with food and one with nothing but “ice cubes and margarine.” She said she is concerned about her finances and will now have to budget differently. The Globe is not naming the patient because she is concerned about repercussions from the divulgence.

Asked by The Globe about the matter, Health Minister Adrian Dix said his ministry and the College of Pharmacists of British Columbia are investigating and the public will be informed when that investigation concludes.

“It is absolutely our intention to take action where evidence exists,” he said Wednesday.

Garth Mullins, a BCAPOM board member and drug user advocate, said the group would like to see incentives legitimized.

“It doesn’t need to be cash handed to us illegally in this undignified way,” he said. “But welfare is so low and everybody is making thousands and thousands off us methadone patients. We should get a bit of it.”

Mr. Mullins said the actions to date have not shuttered problem pharmacies but rather further disadvantaged patients who are most vulnerable.

Lisa Howard is a family physician who provides primary and addictions care in Vancouver. Along with her colleagues, she has reported problem pharmacies to the college on several occasions, but those complaints have not resulted in disciplinary action, to date.

Dr. Howard said that, since the letter went out, two patients have reported that some pharmacies had ceased offering cash payments. However, she said the cash incentives are not her primary concern.

“I can understand how cash incentives may potentially be beneficial to keep people adhering to a treatment that’s helping them,” she said. “It’s certainly not allowed, but I don’t think that is the most harmful thing. The most harmful thing is the haphazard way that the deliveries are done, not being witnessed and not being documented adequately for the people who are prescribing the medication.”