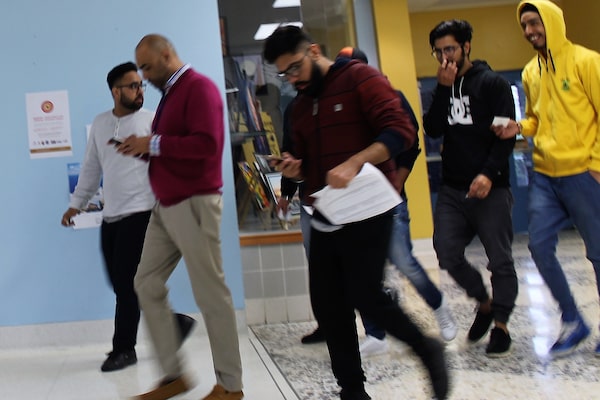

In May of 2017, former Ontario PC leader Patrick Brown, seen third from left in the group of men, has his photo taken by Snover Dhillon, who worked as a campaign organizer for PC Party hopefuls in at least five ridings.Brandon Ferguson/Brandon Ferguson

It was a busy weekend for the Ontario Progressive Conservative Party. On the Saturday, after a nearly 500-kilometre bus trip, a group of Toronto-area residents posed as local voters at a candidate nomination meeting in Ottawa. The next day, the power broker who led the journey was working at another vote in Hamilton, where a printer secretly churned out fake identity papers.

The results of both nominations were bitterly disputed and eventually overturned, along with four other votes. The Tories have never explained those decisions, or what happened inside the party over the last 19 months – how nomination battles were gamed under the supervision of senior officials, alienating party loyalists and attracting the attention of criminal investigators.

New leader Doug Ford says he’s dealt with the disputed nominations that happened under his predecessor Patrick Brown and is focusing on the future. However, questions remain about how some candidates were selected to carry the PC banner. Nomination races, despite being a cornerstone of Canada’s democracy, are not overseen by federal or provincial electoral watchdogs.

A Globe and Mail examination of contentious PC nomination races found widespread evidence of interference in the local democratic process. The most egregious cases involved alleged ballot-box stuffing, ineligible voters and fake memberships. In others, the process appeared to have been manipulated to benefit favoured candidates. Voting dates were moved up, information was withheld by top officials and the screening of contenders was stalled, according to unsuccessful candidates and local riding associations.

There is evidence Snover Dhillon, a businessman convicted of fraud and deemed persona non grata by federal Conservatives, played an influential role in many of the disputed provincial votes, including in Ottawa and Hamilton. The Globe investigation found that Mr. Dhillon worked as a campaign organizer for party hopefuls in at least five ridings. One of Mr. Dhillon’s clients, Brampton East candidate Simmer Sandhu, dropped out of the race earlier this week, after his former employer reported an “internal theft” of 60,000 customers’ names and addresses.

Mr. Ford told reporters on Friday he will not call for an external probe into whether other PC candidates may have been involved. York Regional Police are investigating the data breach. A police investigation into alleged fraud at a PC nomination race in Hamilton is also ongoing.

The Globe interviewed four dozen party insiders about the disputed nominations and obtained internal documents, including e-mails, formal appeals and some membership lists. A data analysis of the lists found numerous red flags: more than two dozen fake members at one Ottawa apartment building linked to Mr. Dhillon or his associates, and large numbers of people with the same address.

Mr. Brown did not respond to The Globe’s requests to comment. He previously declined to overturn nomination decisions after the party received complaints.

The potential for abuse at the nomination level has been repeatedly identified as an issue across the political spectrum at the provincial and federal levels. The alleged vote-rigging demonstrates that the process for selecting candidates must be monitored and regulated the same way as general elections, says Christopher Cochrane, a political science professor at the University of Toronto.

“The democratic process is only as strong as the weakest link.”

From the start of his leadership, Mr. Brown promised to broaden the appeal of the PC Party with a slate of candidates that was youthful, gender balanced and ethnically diverse. He said there would be open and competitive nomination battles.

Competitive nomination battles, as opposed to officials appointing a candidate, generate funds for the party –$10 per member – while building an invaluable database of supporters ahead of the general election.

But political parties face a dilemma when it comes to selecting a slate of candidates, says Prof. Cochrane. They want the process to appear democratic and locally-run; however, party leaders also have preferred candidates.

“You can have a debate about whether the central party apparatus should have more control over selecting candidates or if riding associations should be the ones doing it. I don’t think you’d find much disagreement that it ought to be a transparent process,” he said.

Transparency is central to the controversy that has enveloped the Tories. Numerous would-be candidates and members have accused senior party executives of manipulating local races by leading on candidates in hopes they would sell memberships, while giving an advantage to the preferred winner.

Allegations of unfair treatment emerged in the PC Party’s very first nomination race under Mr. Brown. Tories in Carleton, a new riding in rural south Ottawa, elected a candidate back in November of 2016, long before anyone was paying much attention to a provincial election that was still 19 months away.

The area, traditionally a Tory stronghold, attracted five candidates, including Jay Tysick, a managing partner of a lobbying and communications firm. He announced his intention to run in early October, 2016 and waited to be vetted by the party, a critical approval that would allow him access to the riding’s membership list.

As he tried to rally support, Mr. Tysick began to worry when the date of the nomination meeting was bumped up twice. A week before the meeting, the party told Mr. Tysick his candidacy was rejected. No reason was given. Goldie Ghamari won the nomination. She did not respond to a request for comment.

“It was clear the fix was in,” said Mr. Tysick, who left the party to run as a candidate in Carleton under the Ontario Alliance banner.

A similar controversy erupted that same month in Burlington, a riding the party lost in the 2014 election to the Liberals. Former MPP Jane McKenna was the first to declare her candidacy, hoping to reclaim her old job. Her only rival was Jane Michael, chair of the Catholic school board.

In the summer, Ms. Michael told the party’s executive director, Bob Stanley, she intended to seek the nomination. He encouraged her to run, she said, but also said he hoped Ms. McKenna could be acclaimed. Mr. Stanley declined comment.

For nearly five months, Ms. Michael waited to be vetted by the party’s nominating committee. She said she was only interviewed and approved the night before the vote, leaving her no time to contact the riding’s more than 900 party members.

After the vote, Colin Pye, then chair of the riding association, alleged in a letter to the party that the meeting was “tainted” by numerous breaches of party rules. He alleges that several people who were not on the membership list were permitted to vote without proper identification; unused ballots were left unguarded at one point; and the room where ballots were counted was not secured. He asked for a formal hearing and a new vote, but was rebuffed.

Mr. Pye resigned his position. “The whole mess around the nomination race left a very bad taste in my mouth.”

Snover Dhillon, second from the left, attended a contentious PC Party nomination battle in Ottawa-West-Nepean in May of last year.Supplied

Around the same time, Snover Dhillon, a power broker and friend of Mr. Brown, was quietly helping the PC Party make inroads among voters of Indian descent mainly in the suburbs west of Toronto.

He was also a frequent presence at party events, attending at least a dozen nomination meetings. His role in many of the races – whether he was working for candidates or simply attending as a party booster – remains an open question.

In a recent Facebook posting, Mr. Dhillon said he worked for contenders, providing volunteers and getting supporters out to vote. He did not disclose who hired him.

“The candidates hired me to run their nominations, they signed contract with me and I told them in written statement very clearly that no acclamation is guaranteed,” he wrote. “… Some candidates won the election and some lost.”

When reached by phone in late March, Mr. Dhillon asked The Globe to send him questions by e-mail. He has not responded to multiple requests for a reply.

The relationship between Mr. Brown and Mr. Dhillon, which dates back more than a decade, worried the leader’s senior advisors, according to sources in his former office. The pair had travelled together to India at least once while Mr. Brown was an MP.

Advisors in Mr. Brown’s office said they warned him to stay away from Mr. Dhillon, given his criminal record. Mr. Dhillon’s convictions relate to activities in 2010 - defrauding a bank of $11,500 and a woman of more than $5,000. He was sentenced to probation. He also served 41 days in jail in connection with a fraudulent real estate deal.

Mr. Dhillon came to the attention of the national media during the 2011 federal election campaign, when he was recognized at a campaign event, seated behind then Conservative leader Stephen Harper’s family. Mr. Brown, a Tory MP at the time, said he wasn’t aware of the fraud allegations. “I like to be supportive of anyone, but obviously I wouldn’t be supportive of any conduct that is illegal,” he told Canadian Press. “I’ll obviously keep my distance.”

However, after Mr. Brown became the leader of the PC Party of Ontario in May, 2015, Mr. Dhillon was frequently seen at Tory events. And when the nomination races kicked off over a year later, he promoted his services to would-be candidates.

Patrick Brown is pictured with Jass Johal, far left with glasses, and Snover Dhillon who is at the back with dark turban, white shirt and no tie in May, 2017.Supplied

Mr. Dhillon’s success in helping Jass Johal, a friend, secure the nomination in a riding where three other contenders were also interested made Mr. Dhillon a hot commodity, according to party insiders. Mr. Johal, a paralegal, was acclaimed in Brampton North in November, 2016.

As the schedule of nomination races picked up – in all, 70 took place while Mr. Brown was leader – Mr. Dhillon marketed himself as having a sizable roster of clients. It’s difficult to discern in many cases if candidates hired Mr. Dhillon or if he simply threw his support behind them, whether it was welcome or not.

His efforts to bolster the party remain in an online footprint that includes a poster circulated on social media for an invitation-only barbecue Mr. Dhillon held in Brampton last summer. The poster featured Mr. Brown’s photo above a slate of 17 PC Party contenders. Mr. Stanley, the party’s then executive director who was at the centre of many races plagued by problems, was listed as a speaker.

The barbecue was billed as an event for Youth for You, a not-for-profit that Mr. Dhillon had recently incorporated. Sources said no one in Mr. Brown’s office approved the poster, but he appeared at the event, giving a speech and posing for photos.

The Globe contacted everyone on the poster who is running in the June 7 election to ask about their connection to Mr. Dhillon, namely, Prabmeet Singh Sarkaria (Brampton South), Amarjot Sandhu (Brampton West), Sarah Mallo (Beaches-East York), Kaleed Rasheed (Mississauga East-Cooksville), Nina Tangri (Mississauga-Streetsville), Parm Gill (Milton), Rudy Cuzzetto (Mississauga-Lakeshore), Jane McKenna (Burlington), Stephen Crawford (Oakville), Harjit Jaswal (Brampton Centre) and Sheref Sabawy (Mississauga-Erin Mills). Mr. Crawford responded, saying he was not aware of the barbecue and Mr. Dhillon did not work on his campaign. “I did not know my photo would be on this poster.”

Mr. Gill and Ms. McKenna also said Mr. Dhillon wasn’t involved in their campaigns.

“Snover Dhillon did not support my nomination, nor has he ever supported me as a candidate for elected office,” Mr. Gill said.

“At no time did I hire Mr. Dhillon on my campaign,” Ms. McKenna said in an e-mail on Monday.

Last summer, Snover Dhillon promoted a BBQ with photos of community members, as well as several nominated and hopeful candidates for the PC Party. It’s not known if all of the individuals agreed to be part of the event, which featured former leader Patrick Brown.

The PC Party’s most contentious nomination battles would also feature Mr. Dhillon as a central character.

On the first Saturday of May last year, Conservatives in the riding of Ottawa West-Nepean gathered at a suburban high school to choose between two contenders: Karma Macgregor, a former Tory Senate aide and businesswoman, and Jeremy Roberts, a young political staffer.

Even before the meeting began, the process had already begun to sour for Mr. Roberts. It was known among party insiders that Mr. Brown favoured Ms. Macgregor, in part because of a personal connection – her daughter was not only one of his aides, but had also once dated him. On the eve of the nomination, Mr. Roberts had told the party’s president he was participating in the vote “under protest and with serious reservations,” citing delays receiving the list of PC Party members in the riding and concerns about some entries, including several addresses with seven or more members.

A Globe analysis of the membership list found that more than two dozen fake members listed at one apartment building had the same names as people connected to Mr. Dhillon or his associates through social media. In interviews, two people said they had no idea how their names and Toronto-area phone numbers ended up on a list of party members in Ottawa.

“I didn’t talk with anyone about this,” said Meghna Randhawa, a student who knows one of Mr. Dhillon’s associates. “I’m shocked. … I never heard of these elections.”

In addition, sources allege Mr. Dhillon, who was working for Ms. Macgregor, bused people from the Greater Toronto Area to vote at the nomination meeting.

After voting started, local party stalwarts began to notice an unfamiliar face – who they later learned was Mr. Dhillon – escorting groups of young people. Instead of directing them to vote at the standard alphabetical registration stations, Mr. Dhillon took them to the credentials table, which is normally where voters are sent after encountering snags such as problems with their identification. The credentials desk was staffed by two of Mr. Brown’s aides and overseen by Mr. Stanley.

One small group of people who arrived with Mr. Dhillon stayed the entire time the polls were open, recalled Carlos Naldinho, a party activist who was at the meeting.

“They kept going into the voting area then coming into the common area,” he said.

Sources told The Globe that Ms. Macgregor did not authorize Mr. Dhillon’s actions. She did not respond to questions from The Globe.

In addition, scrutineers with Mr. Roberts’s campaign raised a host of concerns, including that officials accepted questionable identification, such as cellphone photos of ID.

Once the vote counting began, the problems escalated. Two boxes, including the one from the credentials desk, contained ballots that had been folded together in a clump – apparent evidence of ballot-box stuffing. “They couldn’t have landed that way in the box,” said Rob Elliott, a party vice-president who helped count the credentials ballots. A total of 17 votes were disqualified.

However, the credentials box also had 28 more ballots than registration forms filled out at that table, according to riding association officials.

Despite objections from the Roberts campaign, Mr. Stanley accepted the results of the credentials ballot box, which tipped the race in Ms. Macgregor’s favour by just 15 votes.

Mr. Roberts’ supporters vigorously challenged the results. But Mr. Stanley eventually declared Ms. Macgregor the winner. He declined to comment on the nominations when contacted by the Globe.

“I had never in my life – in all my years in politics – seen such blatant fraudulent activity as I saw that day,” said Marjory LeBreton, a former Conservative senator who has been involved in politics since John Diefenbaker was prime minister. “It was just unbelievable.”

A few weeks later, the riding association quit en masse.

The whole mess around the nomination race left a very bad taste in my mouth

— Colin Pye, a former riding association chair

News about the Ottawa irregularities travelled fast as outraged Tories phoned contacts in other parts of the province – including those involved in another nomination vote that was happening the next day in Hamilton.

The race in Hamilton West-Ancaster-Dundas was hard fought between Ben Levitt, a political aide for a federal Tory MP; Vikram Singh, a lawyer; and Jeff Peller, whose family owns the Peller Estates winery.

At the high school where the vote was held, veteran strategist John Mykytyshyn noticed Mr. Dhillon, who was working for Mr. Peller’s campaign, in the parking lot greeting large coaches as busloads of voters arrived.

Behind the scenes, The Globe has learned, a printer was cranking out fake Rogers utility bills and Scotiabank statements in a classroom, according to multiple sources.

Party rules require voters to present photo ID and proof of address. The fake I.D. enabled people who were not eligible to vote to cast ballots.

Officials eventually figured out the alleged scam when they noticed voters using Rogers and Scotiabank statements with identical account numbers and balances, according to party members who were present.

Later there would also be questions about whether votes were cast illegally on behalf of people who did not attend.

Jacob Trenholm, a management consultant, said a Hamilton detective contacted him in January, 2018, and told him police had a list that showed him casting a ballot. Mr. Trenholm had bought a membership at the request of Mr. Levitt, a friend from high school, but did not attend the nomination meeting. “I was surprised and felt uncertain as to what had happened because it felt wrong,” he said.

As in Ottawa, irregularities also occurred in Hamilton at the credentials table, which was staffed by aides to Mr. Brown and overseen by then party president Rick Dykstra. He did not respond to requests for comment.

Mr. Singh had the most votes at the standard stations, but Mr. Levitt received 202 out of the 345 ballots from the credentials table, pushing him to victory, according to a lawsuit Mr. Singh later filed. He alleged the meeting was tainted by party officials’ predetermination that Mr. Levitt would win and by “fraudulent ballot stuffing.”

An e-mail later obtained by the Toronto Star appears to suggest Mr. Brown directed his top officials to influence the outcome of the vote. “Let them all fight it out. And get me the result I want. But no disqualifications here. Kitchen is too hot,” Mr. Brown e-mailed Mr. Stanley just days before the meeting. “Got it,” Mr. Stanley replied.

Hamilton Police launched an investigation into allegations of forgery and fraud in June, 2017, in response to a complaint from Mr. Singh. A Hamilton detective has also interviewed key players from the Ottawa West-Nepean nomination meeting in recent months, The Globe has learned.

Mr. Peller also launched a lawsuit, alleging ballot-box stuffing. He and Singh both eventually reached settlements with the party. The Globe has reported that members of Mr. Brown’s inner circle discussed a possible settlement for Mr. Peller that included $130,000 to cover his campaign expenses, including $22,000 he had paid to Mr. Dhillon. It references “various illegal activities.” No further details were given.

“We ran a clean campaign,” Mr. Peller said, adding he hired Mr. Dhillon to sell memberships in the Indian community.

I had never in my life – in all my years in politics – seen such blatant fraudulent activity as I saw that day

— Marjory LeBreton, former Conservative senator

Just one week after the chaotic back-to-back Ottawa and Hamilton votes, Mr. Brown and Mr. Dhillon socialized together at a party for college students in Brampton.

Mr. Brown’s presence at the party, which featured a buffet, DJ and Punjabi singer, was a surprise even to the hosts. He delivered a few words to the crowd and posed for photos. Afterward in the parking lot, a smiling Mr. Brown posed for a selfie with Mr. Dhillon and Mr. Johal, among others.

Shortly after, Mr. Brown made it clear he had no intention of revisiting any of the disputed races. At a party executive meeting on June 3, he announced the party would not hear any appeals and that accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers would oversee future meetings.

Rob Elliott, the party vice-president, resigned that day over the decision. “I felt that those appeals needed to be heard and there were legitimate questions to be asked,” he said.

In January, Mr. Brown was forced to resign amid allegations of sexual misconduct involving two young women, which he has denied. Interim leader Vic Fedeli was left to deal with the fallout over nomination races plagued by complaints and the party’s inflated membership numbers. Mr. Brown boasted that the party’s ranks swelled to 200,000 from 10,000 under his leadership.

Pledging to “root out the rot,” Mr. Fedeli overturned two nominations, including Ottawa West-Nepean, and eliminated Bob Stanley’s position. Mr. Fedeli also ordered a probe into the names and addresses of all the party’s members. He later announced that the database contained just over 132,000 names, but he never got an opportunity to complete the review.

In March, Doug Ford became leader. The party overturned four nomination races, including Brampton North, where Jass Johal had been acclaimed, and Hamilton West-Ancaster-Dundas. It also barred Mr. Brown from running as a Tory candidate.

At the same time, Mr. Johal and Mr. Dhillon were swept up in a probe by the province’s ethics watchdog, who ruled that Mr. Brown broke integrity rules by failing to disclose a $375,000 loan from Mr. Johal. Mr. Dhillon witnessed a promissory note for the loan during a meeting with Mr. Johal and Mr. Brown in the summer of 2016, the report says.

The party has tried to move forward. After a new race was ordered in Ottawa West-Nepean, Jeremy Roberts was acclaimed as the candidate. In Hamilton West-Ancaster-Dundas, Mr. Levitt won a new vote.

“Anything that happened under the previous leader is in the past and our party is moving forward,” Melissa Lantsman, a spokeswoman for Mr. Ford said.

But the problematic nominations continue to haunt Mr. Ford, who just this week lost a candidate. Simmer Sandhu, who worked for the company that owns the 407 toll highway, dropped out because he did not want to be a distraction. He said allegations made against him relating both to his work and campaign are “totally baseless.”

Mr. Ford’s spokeswoman also said this week that Mr. Stanley has been told he is “not welcome to be a part of our campaign in any role – official or unofficial.”

With files from Justin Giovannetti, research by Stephanie Chambers and data analysis by Tom Cardoso

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/UJUEVI6WG5EYPCKAEPTHDZTSV4.jpg)