A child touches one of the orange flags in Ottawa's Major's Hill Park this past Canada Day. Each flag represents a child who died while attending residential school.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

Bonus podcast • Barometer’s builders speak on The Decibel

What is reconciliation? And how is that process coming along?

On Canada’s inaugural National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, answers to both questions remain elusive. The entire concept has been declared at once dead or thriving, a farce or a hope, a road to hell or a path forward.

Later this year, a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics hope to clear things up by releasing their first forecast of what reconciliation in Canada is, and where it is headed. The project, called the Reconciliation Barometer, is designed to strip out the rhetoric and place the undertaking of reconciliation under statistical scrutiny.

“This barometer will help measure whether or not the social distance that has plagued this country for so long between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples is widening or closing, whether or not attitudes are hardening or softening in regards to Indigenous rights and the recognition of Indigenous rights, and how we’re collectively doing,” said Ry Moran, associate librarian at the University of Victoria and a contributor to the project.

In previous roles, Mr. Moran had been director of statement gathering for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the founding director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

It was when he started that latter role, in 2015, that he realized the need to generate some baseline data on how Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in the country viewed one another that could be tracked over time.

“I think the question about whether or not we are going to succeed at reconciliation was one of the things that weighed heavily on the minds of all people involved in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” said Mr. Moran, a member of the Red River Métis. “And running right alongside of that was a very fundamental recognition that data, transparency of data and ongoing measuring and monitoring of our successes and failures would be an absolutely critical component of the work that lay ahead of us.”

As fate would have it, Katherine Starzyk, an associate professor of social and personality psychology at the University of Manitoba, was exploring the same issue at the same time.

She had attended a UN Development Program workshop in South Africa and realized how far that country had come in measuring its progress – or lack thereof – following truth and reconciliation hearings into apartheid.

“That really got me thinking about what was happening in Canada and how we didn’t have a way to measure it like South Africa, Australia and several other countries do,” said Dr. Starzyk, lead on the barometer project.

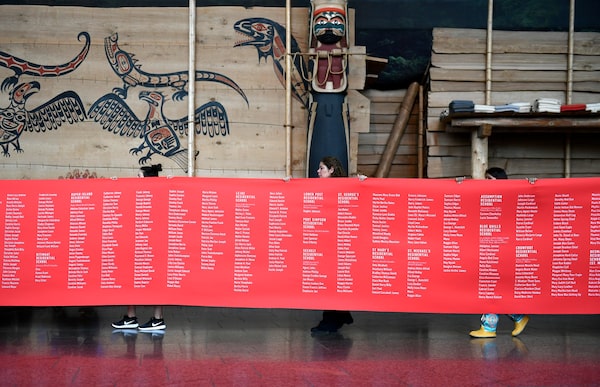

Reconciliation, Canada- and Australia-style: At top, a ceremonial cloth with the names of 2,800 children who died in residential school is carried to the stage in Gatineau, Que., for 2019's Honouring National Day for Truth and Reconciliation; at bottom, an art installation in Sydney called 'Sea of Hands' is part of 2016's National Reconciliation Week.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press; WILLIAM WEST/AFP/Getty Images

The Canadian team started with the most basic of questions: What is reconciliation? Luckily, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had included a standard question about the meaning of reconciliation during witness interviews conducted between 2008 and 2014.

Researchers pored over the testimony and conducted a qualitative analysis, coding what was said line by line. They also canvassed leaders in the social justice realm and examined international reconciliation parameters. From that, they came up with 13 broad indicators that they intend to track over time. Those indicators include awareness of Indigenous history, health of relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, level of Indigenous leadership within various sectors of society, engagement in Indigenous culture, regard for the natural world and issuance of appropriate apologies. The scores can be broken down for specific sectors, such as criminal justice, education, child welfare and others.

“It is so many different things to so many different people,” Dr. Starzyk said. “Some people will identify more with some indicators than others. What I will say is that our items are very valid and reliable. We’ve kind of developed them with excruciating attention to detail.”

The team will provide more findings from their work when it is ready for publication later this fall.

A specialist in psychometrics (the science of psychological measurement), Dr. Starzyk and her team conducted polls and focus groups to gauge national attitudes around each of the indicators. The finished product, they hope, will be an objective look at a fraught relationship.

“Reconciliation will take work and time,” said another team member, Iloradanon Efimoff, a PhD candidate in social and personality psychology at the University of Manitoba who is of Haida and European heritage. “Just because we have a TRC and the calls to action, there’s no guarantee that we are going to end up in a reconciled future.”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, president of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, hands the group's report to then-president Nelson Mandela in 1998.Peter Andrews/REUTERS

The South African Reconciliation Barometer shows just how difficult the path to reconciliation can be. Published every two years based on a 100-question survey of around 2,400 people, the barometer is the forerunner to similar efforts in Australia, Cyprus, Kenya, Rwanda and Sri Lanka.

Recent surveys show that while a majority of South Africans think national unity is possible, just three in 10 say they trust people of other races.

“In many instances, it shows we’re taking a few steps back and a few steps forward,” said Jan Hofmeyr, acting executive director of the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, the think tank that runs the survey.

The South African barometer has needed tinkering along the way. Early surveys focused too heavily on the social integration of racial groups and not enough on economic divisions. Mr. Hofmeyr said the Canadian counterpart might do well to heed that lesson early.

“We should have realized from the beginning that economics matter. It matters in the sense of being able to make a living, but also in terms of dignity, because apartheid robbed the majority of people of dignity,” Mr. Hofmeyr said.

“It created different standards for different people depending on their race, leading to intergenerational poverty. The question of reconciliation is not only about accepting others as equals, but also ensuring that their dignity is restored.”

Truth and reconciliation: More from The Globe and Mail

On the Decibel podcast, host Tamara Khandaker spoke with two of the experts behind the Reconciliation Barometer project, Katherine Starzyk and Ry Moran, about its goals and the significance of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Subscribe for more episodes.

Opinion

Tanya Talaga: All Canadians should take Sept. 30 to observe National Truth and Reconciliation Day