Danny Grossman watches dancers as they perform moves during a rehearsal at a dance studio in Toronto on May 14, 2008.Sami Siva/The Globe and Mail

During a tour of Western Canada in 1978, the members of the Danny Grossman Dance Company performed at the medium-security Drumheller Institution in Drumheller, Alta. During the opening pieces, the prisoners in a gymnasium’s makeshift theatre rowdily hooted and jeered.

They clammed up and dragged their chairs forward, though, when the namesake company founder appeared for his disquieting solo Curious Schools of Theatrical Dancing: Part I. Dressed in a black-and-white harlequin costume, Mr. Grossman presented as a tortured, pathetic buffoon in a circus ring he could not escape. There was rapt attention from the jailed.

“I imagine they saw themselves in Danny’s character,” said Pamela Grundy, a long-time dancer and co-artistic director with the troupe, which stopped performing in 2008. “These were trapped people, tossed around by society and unsure of what to do.”

Indeed, Mr. Grossman’s often unconventional modern dance pieces reflected his compassion for the marginalized. If the dances were sometimes droll, the jests carried weighty implications.

Mr. Grossman, a dancing American who made a name for himself as one of Canada’s great choreographers, died of heart failure on July 29, at Toronto’s Michael Garron Hospital. He was 80 years old.

When Ms. Grundy ushered the San Francisco native into Canada’s Dance Hall of Fame as its first ever inductee in 2018, she characterized her friend and associate as a “shaggy-haired bandy-legged rebel.” The son of social activist parents created more than 60 robust works, some of which entered the repertory of such troupes as the Paris Opera Ballet, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens and the National Ballet of Canada.

His humanism, politics and physically exaggerated style can be traced back to the radical dance experimentalism of the 1950s.

For a decade beginning in 1963, he was a wunderkind member of the iconic, internationally touring Paul Taylor Dance Company, based in New York. In 1973, he and his life partner Germain Pierce arrived in Canada with their miniature dachshund, Lola, in tow. Under his stage name at the time, Danny Williams, he performed as a guest with Toronto Dance Theatre (TDT) at the invitation of Canadian dancer-choreographer David Earle.

He taught at both TDT and Toronto’s York University before forming the Danny Grossman Dance Company in 1976. His witty, bold pieces were marked by a satirical sense of humour and a devotion to progressive ideals.

“If you come expecting dances that sweep across the stage, gulping down space in movements that flow naturally from the bodies of happy, happy people, you’ll be sorely disappointed,” The Globe and Mail’s Stephen Godfrey wrote in 1980.

Mr. Grossman’s made-in-Canada choreography attracted international attention. In 1979, his namesake group became the first international company to perform at the Los Angeles Dance Festival. Lewis Segal of The Los Angeles Times said Mr. Grossman had a “powerful theatrical imagination,” and that the company’s performance had ‘’moments of extraordinary excitement and idiosyncratic innovation.’’

Mr. Grossman’s often unconventional modern dance pieces reflected his compassion for the marginalized.Patti Gower/The Globe and Mail

His 1986 work Hot House: Thriving on a Riff, a tribute to the bebop maestro Charlie (Bird) Parker, was choreographed for the National Ballet of Canada and made its U.S. debut at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House.

His first creation was the 1975 duet Higher, now a Canadian classic. A stepladder and the music of Ray Charles were employed to portray the dicey balancing act of romance. Mr. Grossman once listed Mr. Charles as one of the three major influences in his professional life, the others being celebrated choreographers Paul Taylor and Igor Moiseyev.

Mr. Grossman was a lifelong vinyl collector. As a dancemaker, what he took from jazz and blues music was not swing or structure, but feeling. “In Higher, the dancers ignore the overt danceability of Ray Charles’s songs, appearing instead to be reaching down to a more basic response,” The Globe’s Robert Everett-Green wrote.

A gay man, Mr. Grossman began his career in an era when homosexuality was not widely accepted. A segment of Mr. Grossman’s work relating to gay themes broke barriers. When he attempted to take his provocative Nobody’s Business to Western Canada in 1982, presenters there wanted none of that business.

“They didn’t think it would fit with their audiences,” Ms. Grundy told The Globe. “If you saw the piece now, you would see how far society has come.”

Mr. Grossman’s Passion Symphony, which portrayed dancers as male lovers guided supernaturally toward a sacred union, was inspired by Mr. Pierce, a singer and dancer. The two met in New York on New Year’s Eve in 1962, and lived together for more than 45 years until Mr. Pierce’s death in 2015. Both took up Canadian citizenship.

Describing himself as having been “profoundly influenced by the theatrical masks of tragedy and comedy,” Mr. Grossman created works that dealt with his personal, social, political and spiritual transformation. His Endangered Species from 1981 was inspired by Francisco Goya’s series of etchings, The Disasters of War; 1997′s Hear the Lambs a Cryin’, on the horror of lynching, was set to the music of Black singer-activist Paul Robeson.

Mr. Grossman was raised in a household rich with virtuous troublemaking. His leftist parents, who had taken him to see Mr. Robeson as a child, were eminent peace crusader and women’s rights champion Hazel Grossman (née McKannay) and civil rights attorney Aubrey Grossman. The former was arrested in 1993 at age 81 in a San Francisco protest in support of Palestinians; the latter was best known for his defence of Willie McGee, a black man put to death for an alleged rape, and for his defence of the Native Americans who occupied Alcatraz Island at the turn of the 1970s.

(The American Legion attempted to deny the outspoken lawyer his licence in 1936, claiming that he was unable to take the state loyalty oath without “having his tongue in his cheek.”)

With that agitative heritage at his back, Mr. Grossman used his 1976 piece National Spirit to lampoon patriotism and mock the U.S. Bicentennial. The piece earned cheers, boos and laughter. He once took it to a school in Florida’s Miami-Dade County, where the principal and a sheriff escorted him off the property.

“That’s going to take me 10 years to undo what you just did,” the principal told Mr. Grossman.

“I think Danny was totally proud of that,” Ms. Grundy said. “He was very conscious of what his parents stood for, and he had caused a ruckus.”

As a dancer, a young Mr. Grossman was hailed by The New York Times as a “whiz of an energetic virtuoso with an especially light jump.” He was considered watchable by sophisticated crowds and neophytes alike. “A lanky body and incised features give Mr. Grossman the physical presence which makes his enormous choreographic and dancing gifts credible to an uninformed audience,” The Globe’s Ray Conlogue observed.

The torquing, twisting profession took its toll – both hips had been replaced by the time he performed his last show in 2018. The duet Labour of Love, created for himself and long-time troupe member Eddie Kastrau, had the two dancers coasting on roller-wheeled stools.

“On those wheels, he could move across the stage faster than anyone could run,” recalled Mr. Kastrau, who joined Mr. Grossman’s company in 1986.

As a conceptualist, Mr. Grossman employed his loyal dancers artistically. “He used them as paint on a canvas to create the image he had formulated in his mind,” Mr. Kastrau said.

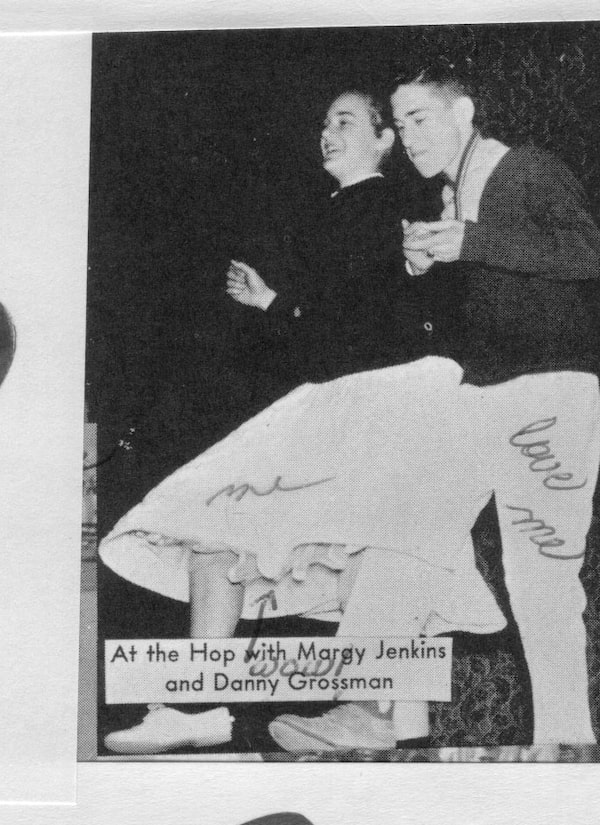

A yearbook photo of Mr. Grossman and Margy Jenkins dancing.Supplied

The Danny Grossman Dance Company shut down in 2008. Diminishing public grants were blamed. Mr. Grossman’s earnest, socially conscious works had fallen out of favour with audiences and arts councils.

A pivoting Mr. Grossman and his team established an institute to archive and license the company’s repertoire for independent choreographers, dance companies and training schools.

“I’m a survivor because I’m a realist, and I think we’re ahead of the curve on preservation,” Mr. Grossman said. “I’m not bitter. I’ve had a fantastic life.”

Daniel William Grossman was born Sept. 13, 1942, in San Francisco. He attended Roosevelt Middle School and George Washington High School, where he led football field cheers and performed at school assemblies with future acclaimed choreographer Margaret Jenkins. Once, while dancing on stage to the hits of the day, the pair had the curtain lowered upon them by the high school principal before they were finished because of the scandalous hip shaking – this in the age of Elvis.

“Danny wasn’t studying dance, but it became clear as we started to boogie, as they called it in those days, that Danny was really quite phenomenal,” Ms. Jenkins told The Globe. “He was much more agile at all of it than I was.”

After his parents took him to see the celebrated Russian folk-dance troupe Moiseyev Dance Company, he took to imitating the dramatic feats of the male dancers, bruising and spraining himself in that ambitious effort.

As a teenager, he was consumed by the mid-century jazz, blues and rock ‘n’ roll that eventually found itself in his choreography. “It all started in the record booths of my youth,” he told The Globe in 2001. “The hook goes back to those days.”

The dancing inspirations of his youth were Donald O’Connor, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire and actor Charlie Chaplin. He studied modern dance under Welland Lathrop and Gloria Unti, before hitchhiking to the East Coast.

“The Danny I knew was absolutely consumed with the joy of moving, and sharing that joy with anybody who wanted to watch,” said Ms. Jenkins, a pioneer of West Coast dance.

In the summer of 1963 at a party that closed the American Dance Festival in New London, Conn., the young man described in a Dance Magazine profile as “a wiry, robust dancer with unruly dark brown curly hair” caught the attention of the celebrated Mr. Taylor, who dubbed him “Pony” and invited him to his New York studio for classes.

Apparently, he was an attentive student, as he quickly joined the Paul Taylor Dance Company and spent 10 years working under the auspices of a true titan of early modern American dance before embarking on his extensive career in Toronto.

Conscious of the lineage of modern dance, Mr. Grossman kept noteworthy works by other choreographers alive by introducing them into his company’s repertoire. Pieces by Canadians such as David Earle, Anna Blewchamp, Randy Glynn and Paula Ross might otherwise have been forgotten.

He also archived extensive materials including videos that would allow for the future reconstruction of his own pieces. “He didn’t want to simply leave behind a series of papers,” Ms. Grundy said. “The intention is to continue to put the works in the bodies of young dancers.”

His pieces have been performed by training institutions including Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, New York State Summer School of the Arts, Adelphi University, City College of New York, Brown University, York University, the Canadian Children’s Dance Theatre and Toronto Dance Theatre.

Mr. Grossman leaves his sister, Kathy Herman. The death of his partner eight years ago was a major blow – he had never lived alone before.

The last piece the fierce environmentalist choreographed was last year’s Earth: Womb of Life (A Pantomime for Our Time), in collaboration with Jackie Latendresse and Saskatoon’s Free Flow Dance Theatre. More recently and in failing health, he completed a short video, Dancer for Life.