You might say: 'Oh, but I would have noticed that bus in time.' Maybe.

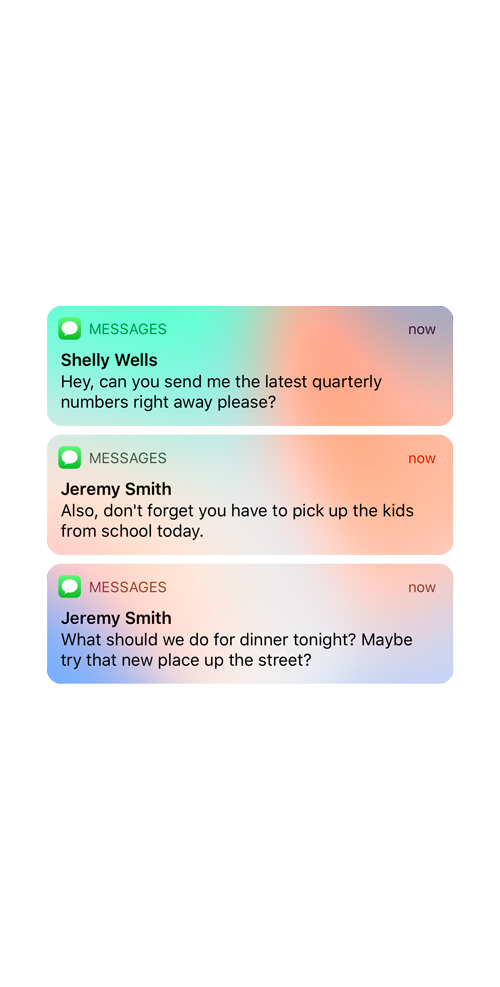

It’s a brightly coloured object near the centre of your field of vision. But here’s another question: While we were putting phone alerts and other text on the screen …

It's understandable if you didn't notice. Between the road, the text and the phone, we were deliberately giving you a lot to try to pay attention to.

But how does that work? How can you be looking right at something and still not see it?

The fact is that people aren’t always very good at processing what’s in their field of vision. This can be particularly stark in cases when an unexpected object appears while the person is focused on something else.

In a famous experiment from 1999, test subjects were shown a video of actors tossing basketballs around and asked to count how many times the people wearing white shirts made a pass. If you feel like trying the test yourself, this is the video:

For a lot of viewers something seemingly impossible happens. As the actors are passing the ball, these viewers, doing their best to watch closely, miss something obvious. Something really obvious. In mid-action, an actor in a gorilla suit walks through the scene, beats her chest and moves on – and they don’t see her.

In fact, the experiment found that only about half of the test subjects noticed the gorilla. Why? Because they were told to focus on the ball, and on white. A black gorilla shape didn't fit their expectations, or their task, so they didn't see it.

Much more than a video experiment, driving requires close attention to a complicated scene.

If you think you can focus on both your phone and the road, you can’t. Not really. You're never really multitasking.

Your brain – specifically, a part called the prefrontal cortex – is shifting attention one task at a time, like a switchboard. If this happens quickly enough, it might seem as though you’re doing two things at once. But you’re not. You're distracted without really knowing it.

Okay, we were doing our best to distract you there. But even if you were able to read, it was more difficult to focus, right?

Piloting a multitonne vehicle carries inherent risk and when things go wrong it can get dangerous fast. That’s why distracted driving is blamed for a rising number of collisions, while using a phone on foot is cited as a factor in only a tiny percentage of the deaths listed at the Fatality Analysis Reporting System, a massive U.S. database.

Numerous studies have shown that using your phone while driving is a dangerous risk to take. One of the most widely cited was based on a three-year analysis of 3,500 drivers under real-world conditions, published in 2016 in the U.S. journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This research showed that distraction in all its forms happened often and doubled your risk of a crash. Specific actions were even riskier.

“Cellphone activities have changed even in recent years with the emergence of texting and browsing online,” the report concluded.

“This is probably the single factor that has created the greatest increase in U.S. crashes in recent years, working against the general trend of crash and fatality reduction.”

The research pinpointed how different types of cellphone usage increased the risk of crashing:

When you’re behind the wheel, inattention can come at a huge, life-changing cost. If not for you, perhaps for an innocent bystander.

In 2018 Larisa Mann was seriously injured after being pinned under a car that struck her while she sat at a transit stop.

Her lawyer says it was a chain-reaction crash he believes is rooted in distraction, with one driver exiting a gas station and ramming straight into another vehicle. That second vehicle ended up on Ms. Mann, leaving her badly injured.

She suffered several fractures and the skin and muscle was torn off her lower left leg. Then 60 years old, she spent a month recovering in the hospital. More than a year later she is still recuperating – both physically and mentally.

She works on her strength twice a week at the gym. When she’s able, she also attends chiropractic, massage therapy and counselling appointments.

Her emotional trauma persists and even now she finds herself nervous around vehicles.

So how big of a problem is distracted driving in Canada? Well, it’s complicated.

Police forces, insurers and Transport Canada agree the problem has become worse.

Figures from the National Collision Database show that the number of crashes related to all forms of distraction started climbing sharply in the late 1990s. After a brief dip last decade, this number has been consistently high for years, averaging nearly 85,000 annually since 2010.

And distracted driving incidents are making up an increasing portion of collisions resulting in injury or death.

Police in the country’s biggest cities say that impaired driving charges are now dwarfed by the number of tickets being handed out for distracted driving.

But distracted driving covers more than just phone use. And the number of tickets doesn’t reveal how often the infraction is committed.

One of the problems with catching distracted drivers is that using a phone is not like nabbing a driver who had been drinking. With distraction, the person currently has to be caught in the act, prompting some police forces to mount side-facing cameras on their cruisers.

Another issue is that the offence isn’t always easy to see. In some Canadian cities, officers have taken to riding on bicycles or transit buses to get a higher vantage point that lets them look down into adjacent vehicles.

The Australian state of New South Wales is rolling out cameras that will take pictures from above of distracted drivers. The effort comes after a pilot project nabbed 100,000 scofflaw drivers, including one using both hands on a phone while the passenger steered.

Aside from being a difficult problem to measure, it’s proved a very difficult one to address.

Catching and punishing people hasn’t been enough to change the behaviour of the broader society. For some recidivists, it hasn’t been enough to change even their own behaviour.

Smartphones have become a crutch for many, a borderline addiction for some. But it goes beyond that. Studies show that most people think they’re an above-average driver, which helps convince them that it’s okay if they use their phone. It’s those other people who need to be stopped.

A study this year for Desjardins Insurance demonstrated how far people are willing to go to excuse themselves. It showed that 53 per cent of Candians admitted having driven while distracted by a phone, at least once. But fully 93 per cent said they rarely or never drive distracted.

This dissonance helps explain why some safety experts now question whether higher fines and stiffer penalties can really address the problem. People don’t see themselves as the culprit. But if society can’t enforce its way out of this situation, what are the alternatives? After dozens of interviews, here are some ideas that were raised.

There’s reason to be honest about our limits, without using that as an excuse to give up. Neil Arason, author of No Accident: Eliminating Injury and Death on Canadian Roads, believes that perfection can’t be the goal. Distracted-driving risk won’t be eliminated, he argues, so interim measures to make people safer need to be pursued.

Do you agree or disagree? What do you think is the best way to keep yourself and others distraction-free on the road?

This is by no means a comprehensive list, of course. Got another idea? Let us know below.

Credits: Reporting and writing by Oliver Moore; Design and development by Christopher Manza; Multimedia editing by Laura Blenkinsop; Photography by Deborah Baic; Photo editing by Patrick Dell; Additional editing by Evan Annett and Dawn Calleja; Illustrations by Murat Yukselir

Additional photo credits: Highway 99 between Vancouver and Whistler in April 2015. Photo by Jeff Vinnick / The Globe and Mail; An LRT train on Ottawa's new transit line in October 2019. Photo by Justin Tang / The Canadian Press