News photographs stop time. It’s their most profound accomplishment. They freeze a moment of the present so that the moment can be examined more closely in the future. An archive like this – a century, as of this month, of photographs taken by Globe and Mail staff photographers – thereby becomes a succession of stopped moments. If you string them together and look at them long enough, patterns start to emerge.

There are a lot of pictures of crowds in this selection, which has been culled from the millions of images Globe photojournalists have taken over the past 100 years. It was not so long ago that crowds were an unusual sight in a mostly rural country, and the pictures reflect that excitement. There are pictures of cities going up (railway tunnels are bored, streetcar tracks are laid, buildings are erected) as that rural country becomes more connected and urban. There are happy pictures of diversions (agricultural fairs and hockey games and beauty contests and ballets, among others) and war pictures of pain and destruction and death. There are lots of cars, because cars have changed the way we live, then as now. (Traffic in Toronto doesn’t seem to have improved.) There are multiple pictures of car crashes from the 1920s to the 1960s because, along with fires, those were the most common free spectacles of their day. They were “proof” that life was increasingly mechanical and dangerous, and therefore moving beyond our control.

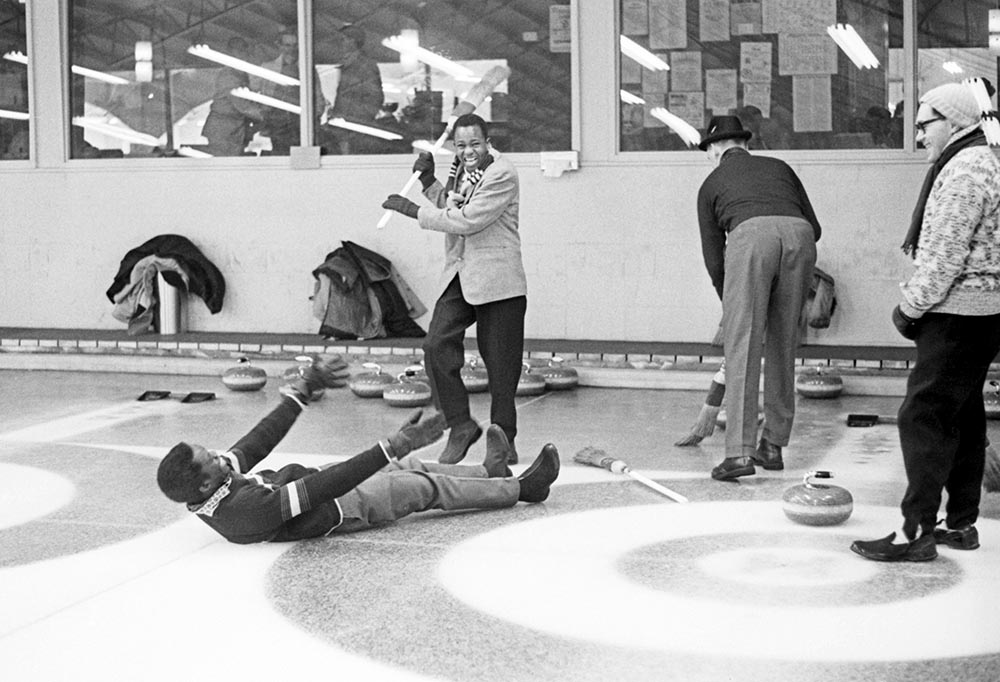

For the first 50 years covered by this collection, the vast majority of people in the pictures are white. And most of them are men. Black and Indigenous people show up rarely, and often as curiosities, as outliers to the status quo. But pictures from more recent decades tell a different story, about an undeniably diverse and changing country, and about the evolution of photojournalism. Most of the photographs in this collection, for instance, treat the world and the people in it as spectacle, as objectively observed phenomena removed from the photographer. But you will occasionally see more recent photographs, taken literally from the point of view of the participants – when the Raptors won the championship, when Canada’s women’s soccer team took Olympic gold – that challenge that separation, that interrogate (without rejecting it) the very idea and value of objectivity.

This work, in other words, is evidence of our progress and our backsliding, a material record of social change. The photographs don’t moralize; they blame everyone and no one at once. They are often beautiful, in spite of their subjects: clean, sharp, filled with movement and light. But they are never only beautiful: their main goal, always, is to grab the attention of the reader and make a connection with them or her or him by depicting something that is happening in the now of that moment. Photographers have always traded in human attention, the most coveted commodity we have and now the scarcest. Their photographs are infused as a result with what philosopher Walter Benjamin once called “unprejudiced observation.” It’s a grabby kind of energy. No subject is beyond consideration: clothes, jobs, bodies, race, buildings, food, leaders, losers, crime, sport, the heat, the cold (winter is ubiquitous), vacations, vanity, the rich and famous (more often than the poor and destitute, alas), shopping, children, hope and despair, sorrow and glee. But whatever these photographs are about, whatever they are meant to connote and denote, they are first and foremost about looking. Newspaper photographers have always fed our deepest if slightly embarrassing hunger: to look at ourselves, to see who we were and who we have become, as a human community.

In general, the men and women who tell stories through photographs are not the same people who tell the stories through words. The main exception to this rule has been the paper’s earliest China correspondents, after The Globe and Mail became the first Western newspaper in the world to open a bureau in Beijing in 1959 – journalists such as Norman Webster and John Burns, who had to be two-way men because local photographers weren’t available to The Globe in China. (Ross Munro and John Fraser relied on their wives.) The first photographs taken by The Globe’s very first China hand, Fred Nossal, of local women lined up for rations during the deadly starvations under Mao, were snatched up and republished all over the world. People want to see what no one has seen before, and that is what photojournalists try to give them.

It might be a good idea to indulge our desire to see ourselves through the eyes of dispassionate professionals while we can. The photographic image was invented in the 1830s by either Louis Daguerre or Henry Fox Talbot, depending on your point of view. The camera itself started out as a toy for rich people, but quickly revealed itself as a kind of universal, morally neutral tool; one capable of documenting reality, on the one hand, but also of creating propaganda and furthering the interests of warmongers and ideologues and capitalists alike. The best photojournalists have resisted those pressures, and many others.

The prospect of using colour photographs gave The Globe pause: some people thought colour was cheesy. So did digital photography, which Globe photographers were converting to by the late 1990s. Digital technology made taking photographs easier, but controlling the ensuing flood of images was a nightmare. “Digital is when the volume of photographs increased exponentially,” Paula Wilson, The Globe’s photo archivist, will tell you. She is a master of understatement. She also shared much of the research that made this collection possible. The Globe was the first newspaper in Canada to set up a digital archive to store the swelling tsunami of digital pics. Even so, it took six months – and six months of lost images – for the photo editors to figure out how to use it.

Today, the world is awash, even drowning, in photographs, thanks to the camera in every smartphone. Digital photographs can be faked by enemies and algorithms alike; they can be obliterated by governments; they can be censored by Facebook and Twitter. Photography’s ubiquity has never been greater, yet its credibility has never been lower. “People’s expectations of photography are changing,” Globe visual journalist Melissa Tait said to me a while ago. She sounded a little sad as she said it. “I often wonder whether photography matters as much as it used to.”

That hasn’t stopped her and her colleagues – whether staff or freelancers around the world, on whose work The Globe frequently relies – from seeing the world through their own eyes, and making a continuous record of what they see, regardless of what they see.

We ought to be grateful for their stubborn commitment to that project. It’s fashionable these days, especially among people who have political axes to grind or little understanding of how the media actually work, to denigrate mainstream outlets such as The Globe and Mail, and to claim that “citizen’s journalism” is a truer record of human affairs than the curated work of professionals.

But that’s rubbish, and you can prove it. Take out your own phone now, as I am doing, and glance over the hundreds and thousands of pictures you have taken – most of which, if you are like me, you never looked at more than twice. What do they tell you about the community we all inhabit together? If your feed is like mine, very little and nothing intentionally universal. The pictures are too personal, too enclosed, too private, too protective, too inept, too flattering, too afraid.

Now look again at this selection of work by some of The Globe’s best photographers, men and women trained to be at once instinctively open to an arresting image, but dispassionate and impersonal about the stories their pictures tell. Take the time to look at the photographs, to sink into their bottomless appeal. The longer we look at them, the more they hold us, caught up in a moment, trying to find what we missed in our furious passing.

-Ian Brown

Content warning:

The following images contain a wide range of human experience – including depictions of graphic content, death, destruction, racism and violence. Viewer discretion is advised.

Want to buy a print?

For images from 1922 to 1952 contact City of Toronto Archives, for 1952 to 2022 contact The Canadian Press

Credits

- Story by Ian Brown

- Biographies by Ian Brown and Angela Pacienza

- Interactive design and development by Christopher Manza

- Editing by Philip King

- Archival research by Paula Wilson

- Photo editing by Deborah Baic, Solana Cain, Taehoon Kim, Mackenzie Lad, Theresa Suzuki, Melissa Tait and Paula Wilson

- Visuals editing by Liz Sullivan and Danielle Webb

- Additional research by Evan Annett, Patrick Dell, Samantha Edwards, Caora McKenna, Sayed Salahuddin, Abigale Subdhan, Jessie Willms, Ming Wong and Rebecca Zamon