Canadian Space Agency astronaut David Saint-Jacques waves upon uniting with the rest of the crew members on the International Space Station on Dec. 3, 2018.NASA/Reuters

Canada’s newest celestial traveller, David Saint-Jacques, greeted fellow astronauts and waved to everyone back on Earth as he took up residence on the International Space Station on Monday, fulfilling a childhood dream to go to space.

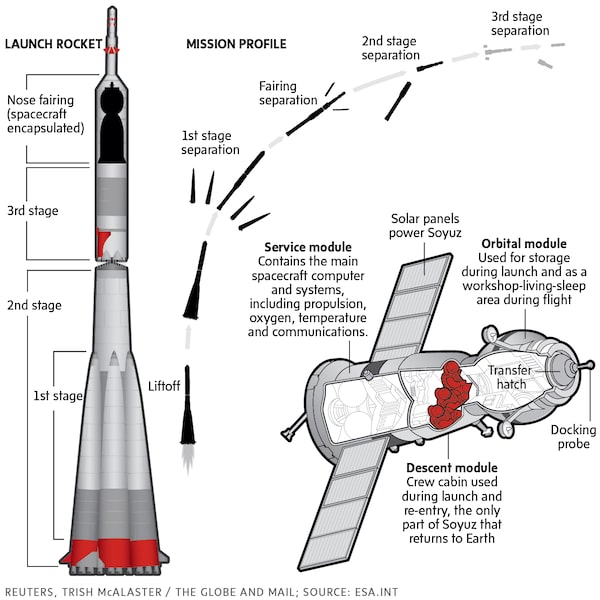

Easy to spot with a bold maple leaf design emblazoned across his jumpsuit, the Quebec-born astrophysicist-physician floated through the hatch of his MS-11 Soyuz capsule about 2:37 p.m. (ET), a little over eight hours after he and two crewmates lifted off from the Baikonur launch facility in Kazakhstan.

“You are representatives of the world’s future,” said Governor-General and former astronaut Julie Payette, who was at the launch and who was first to welcome the new arrivals during a radio call with Earth.

A few minutes later, while speaking with his wife, Véronique Morin, for the first time since reaching the station, Dr. Saint-Jacques said the experience had left him at a loss for words.

“I’m astonished by what I’ve seen,” he said in French as the station sailed 409 kilometres above the Arabian Sea. He added: “I know you’re all there with me in my heart.”

Watch a recap of the Soyuz rocket launch that carried David Saint-Jacques and two other astronauts into space.

Dr. Saint-Jacques’s safe arrival at the Earth-orbiting facility, together with veteran Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko and U.S. astronaut Anne McClain, was just one part of an action-packed day for Canada’s space program.

At 12:09 p.m. ET Monday, an unmanned NASA probe called OSIRIS-REx officially reached its destination: a small asteroid named Bennu, currently located about 122 million kilometres from Earth.

OSIRIS-REx carries a Canadian-built lidar – a measuring tool that will use laser light to scan the asteroid’s boulder-strewn surface and help guide the spacecraft in its efforts to capture a sample to bring back to Earth. The device is Canada’s first technical contribution to planetary exploration in over six years.

Canadian Minister of Science and Innovation Navdeep Bains, left, watches the launch at the Canadian Space Agency headquarters in St. Hubert, Que.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

After a public viewing of Dr. Saint-Jacques’s launch at the Canadian Space Agency’s headquarters near Montreal, Navdeep Bains, federal Minister for Industry, Science and Economic Development, praised Canada’s history and capabilities in space. But Mr. Bains did not take the obvious opportunity to offer any words on the future of Canada’s space program.

Canadian scientists and companies who are active in the space sector have been urging Ottawa for more than a year to produce a coherent strategy and accompanying budget for the space program that would revitalize the sector and aid in long-term planning.

On Monday, Mr. Bains would only reiterate his pledge to produce the strategy in “the coming months.”

Canada faces a more pressing timetable when it comes to whether it will join with international partners in the next phase of human space exploration – a remote outpost called the Lunar Gateway that the U.S. space agency, NASA, aims to place in orbit around the moon.

NASA has lately been vocal in its overtures to Canada in hopes that the Trudeau government will join the project. While noting the inspirational impact that space exploration has on young people in science and engineering, Mr. Bains said that several other factors are feeding into Ottawa’s deliberations.

A Soyuz booster rocket launches the astraonauts in a Soyuz MS-11 spacecraft from the Baikonur Cosmodrome.NASA/Getty Images

Scenes of Dr. Saint-Jacques’s eight-minute ascent to space captivated a packed auditorium of about 400 people, including agency staff, family members and media who had gathered for the pre-dawn (local time) events.

“David is an astronaut now – he’s in orbit,” said Robert Thirsk, a Canadian former astronaut who was providing impromptu colour commentary, as the audience erupted in applause.

For the next few days, Dr. Saint-Jacques and his crewmates will need to acclimatize to life in space as they commence their work aboard the station including a raft of science experiments and other duties.

“If you look at his schedule right now, it’s already jam packed,” said Mathieu Caron, senior engineer for payload operations with the Canadian Space Agency.

The new arrivals are also preparing for an unusually quick hand-off when the station’s current residents depart in less than three weeks.

The short overlap is the result of an aborted Soyuz launch in October, when two other crew members who were heading for the station were instead pitched back to Earth after a malfunction destroyed their rocket.

Monday’s successful launch marks a crucial return to flight for the Soyuz system, which is currently the only vehicle capable of getting people to the station, at least until SpaceX and Boeing begin the first commercial crewed flights to the station in 2019.

Since Marc Garneau became the first Canadian in space just over 35 years ago, the Canadian Space Agency has sent nine astronauts into orbit, including David Saint-Jacques. In 2009, Cirque du Soleil co-founder Guy Laliberté became Canada’s first space tourist when he paid his own way to the station. And earlier this year, Drew Feustel, a U.S. astronaut who holds Canadian citizenship made his third trip to space as commander aboard the station.

In contrast, Canada has been only a modest backer of robotic probes sent to other planets, though many Canadian scientists have contributed to the field through their individual connections with planetary missions flown by other countries.

The lidar on OSIRIS-REx is a notable exception. In exchange for Canada providing the device, Canadian scientists will have access to the asteroid material it brings back to Earth, giving them the chemical clues to the formation of the planet.

An artist's rendering of the OSIRIS-REx probe, sent to map the near-Earth asteroid Bennu.

“What you have there is pristine material from the early solar system,” said Erick Dupuis, director of space exploration development for the space agency.

Michael Daly, who is a professor at York University in Toronto and principal investigator for OSIRIS-Rex lidar, said the Canadian instrument is scheduled to be used for the first time on the asteroid on Tuesday and then again on Thursday.

“We are really excited to finally be close enough to use the Canadian instrument,” said Dr. Daly, speaking with The Globe and Mail from the University of Arizona in Tucson where the probe’s science operations are based.

Multimedia feature: The road to David Saint-Jacques's launch into orbit

How a shuttle launches: A visual guide

THE LAUNCH SITE

RUSSIA

KAZAKHSTAN

Baikonur Cosmodrome

UZBEKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

0

650

TURKMENISTAN

KM

CHINA

AFGHANISTAN

IRAN

PAKISTAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

RUSSIA

KAZAKHSTAN

Baikonur Cosmodrome

UZBEKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

0

650

TURKMENISTAN

KM

CHINA

AFGHANISTAN

IRAN

PAKISTAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP

CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

RUSSIA

KAZAKHSTAN

Baikonur Cosmodrome

UZBEKISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

TURKMENISTAN

0

650

TAJIKISTAN

KM

CHINA

AFGHANISTAN

IRAN

PAKISTAN

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

THE LAUNCH

How to park a Soyuz

The International Space Station orbits about 400 kilometres above the Earth (green). To get to the station the Soyuz capsule first enters an insertion orbit (blue) at an altitude of 220 km. A lower orbit means it is moving faster than the station and can begin to catch up.

Soyuz

ISS

Next, the Soyuz climbs up to a higher orbit (red), about 100 kilometres lower than the station’s, by using a fuel efficient “Hohmann transfer” manoeuvre that requires two engine burns, one at the beginning and one at the end of the manoeuvre.

Once final calculations have been made,

the Soyuz uses a three-burn “bi-elliptic transfer” manoeuvre to match its trajectory with that

of the space station. During final approach,

the Soyuz docks to the station automatically with astronauts ready to take over if there

is a problem.

Note: Graphic is purely schematic.

Drawings are not to scale.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: ESA.INT

The International Space Station orbits about 400 kilometres above the Earth (green). To get to the station the Soyuz capsule first enters an insertion orbit (blue) at an altitude of 220 km. A lower orbit means it is moving faster than the station and can begin to catch up.

Soyuz

ISS

Next, the Soyuz climbs up to a higher orbit (red), about 100 kilometres lower than the station’s, by using a fuel efficient “Hohmann transfer” manoeuvre that requires two engine burns, one at the beginning and one at the end of the manoeuvre.

Once final calculations have been made, the Soyuz uses

a three-burn “bi-elliptic transfer” manoeuvre to match its trajectory with that of the space station. During final approach, the Soyuz docks to the station automatically with astronauts ready to take over if there is a problem.

Note: Graphic is purely schematic.

Drawings are not to scale.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: ESA.INT

The International Space Station orbits about 400 kilometres above the Earth (green). To get to the station the Soyuz capsule first enters an insertion orbit (blue) at an altitude of 220 km. A lower orbit means it is moving faster than the station and can begin to catch up.

Next, the Soyuz climbs up

to a higher orbit (red), about 100 kilometres lower than the station’s, by using a fuel efficient “Hohmann

transfer” manoeuvre that requires two engine burns, one at the beginning and one at the end of the

manoeuvre.

Once final calculations have been made, the Soyuz uses a three-burn “bi-elliptic transfer” manoeuvre to match its trajectory with that of the space station. During final approach, the Soyuz docks to the station automatically with

astronauts ready to take over if there is a problem.

Soyuz

ISS

Note: Graphic is purely schematic. Drawings are not to scale.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL; SOURCE: ESA.INT

THE INTERNATIONAL

SPACE STATION

After braking to slow down

and match the speed of the ISS,

the Soyuz connects to one

of the station’s Earth-facing

docking ports.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

THE INTERNATIONAL

SPACE STATION

After braking to slow down

and match the speed of the ISS,

the Soyuz connects to one of the

station’s Earth-facing docking ports.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

THE INTERNATIONAL

SPACE STATION

After braking to slow down

and match the speed of the ISS,

the Soyuz connects to one of the

station’s Earth-facing docking ports.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL