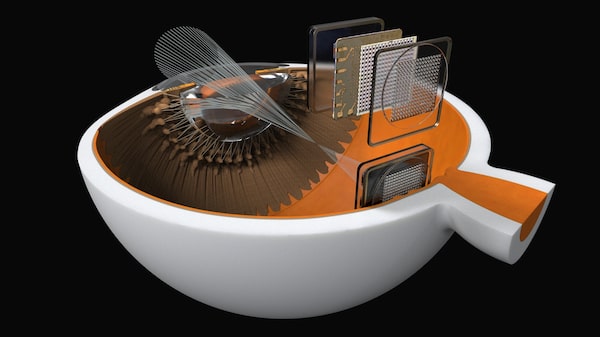

The Diamond Eye implant is surgically placed in the back of the eye. Data from a camera mounted on a pair of eyeglasses is sent wirelessly to the implant. The implant translates the data into signals the brain can understand.

People of a certain age may remember how big the switch to colour television from black-and-white was several decades ago. It was like going from an image that was merely functional to one that was vibrant and alive.

The idea is similar for iBionics, an Ottawa-based company that is working to improve the effectiveness of vision-restoring technology. With its Diamond Eye implant, the company believes it can help blind people recover a new level of visual clarity.

“It’s essentially a bionic retina,” says co-founder and chief executive officer Suzanne Grant. “We want to do for blind people what cochlear implants are doing for deaf people.”

The best current option as far as bionic eye implants go is the Argus II retinal prosthesis, which received regulatory approval in the United States in 2013 and in Canada in 2015. California-based manufacturer Second Sight Medical Products Inc. sold more than 75 implants worldwide last year, following 42 in 2016.

The Argus II is meant to counter the effects of retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disorder that causes loss of vision.

The system connects a pair of glasses to an implant on the patient’s retina. A small processor device worn by the user interprets images seen by a camera mounted on the glasses and sends the information to the implant, which changes it into signals the brain can understand. The result is partial vision restoration where recipients are able to see shadows and shapes.

That may not seem like much to people with full vision, but recipients have been ecstatic with regaining even some sight.

Ms. Grant believes iBionics can go further. The Diamond Eye implant – which is made of diamond materials and measures about four by four millimetres square and one millimetre thick – works similarly to the Argus II, with a few key differences.

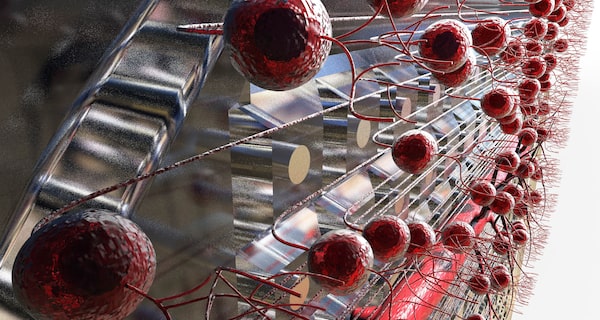

The implant has 256 electrodes, or about four times that of its competitor, according to the company. The higher density means recipients will be able to see full images, including facial details. The electrodes stimulate ganglion cells, which are the retina’s final output neurons. The brain then interprets those electrical signals as the image being seen, effectively recreating what the eye is missing.

The electrodes stimulate ganglion cells, which are the retina’s final output neurons.

The iBionics implant also sits at the back of the retina and receives information from the glasses wirelessly, which means no cable is necessary. That will translate into a simpler surgical procedure.

“[In the Argus II] it’s a fairly large cable that connects the inside of the eye to the outside and that gives us some challenges and potential for complications,” says Flavio Rezende, a Montreal-based surgeon who has performed three Argus II implants, with a fourth scheduled for next month.

Dr. Rezende joined iBionics as chief clinical officer and is charged with designing the Diamond Eye’s surgical procedure. He believes the process can be done in two hours, about half of what it has taken him to implant the Argus II, with only local rather than general anesthetic .

Much of the Diamond Eye’s basic technology was invented by professor Steven Prawer in Australia. While Dr. Prawer was able to receive enough funding to develop the implant, he had trouble finding a way to commercialize it in Australia.

He met Ms. Grant, who had previously founded a communications company in Qatar and worked as an engineering officer with the Canadian military, while on sabbatical at the National Research Council in Ottawa.

“We want to do for blind people what cochlear implants are doing for deaf people,” says iBionics co-founder and chief executive officer Suzanne Grant.

The duo founded iBionics in 2015 and have attracted $15-million in private and public financing. The company has six full-time employees, with about 40 people overall in various part-time consulting roles.

iBionics is targeting full approval and commercial availability by 2024, a relatively ambitious timeline that is helped by the Argus II already having done the heavy lifting with regulatory clearances.

“The main big barrier has already been broken, now it’s a matter of improving the technology,” Dr. Rezende says.

Implant-oriented companies are facing technological competition, with other researchers working on stem-cell- and gene-based therapies. Experts, however, believe implants represent the best near-term option for restoring vision.

“The other two are going to take a lot longer,” says Keith Gordon, former vice-president of research at the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. “It’s going to take years before governments allow you to start doing anything with it. This is more immediate.”

Argus II developer Second Sight is also working on Orion, its own wireless device that is implanted directly onto a patient’s visual cortex. The company is in early stages of testing.

Both companies are tackling a growing market. About 200 million people worldwide will live with retinal conditions leading to blindness by 2020, according to iBionics. In 2017, the direct and indirect costs of blindness in Canada amounted to $19.8 billion, according to the CNIB.

Experts are optimistic about the coming second generation of bionic implants, but also warn that expectations need to be managed.

The technological improvement is indeed likely to be a shift akin to moving away from black-and-white TV, but it won’t quite be high-definition just yet. Implant recipients will be able to move beyond just seeing shadows to full images, if the Diamond Eye works as promised, but they are still not likely to be able to make out text, for example.

“There’s a lot in the retinal processing to the optic nerve that we just don’t understand,” says John Zelek, co-director of the Vision and Image Processing Lab at the University of Waterloo. “It will provide some vision, but you’re not going to get it the way it was.”

Vision of the future

Lieutenant Commander Geordi La Forge of Star Trek.Supplied

X-ray vision, infrared awareness, telescopic vision – it’s all science fiction, right?

It is, in a sense, but when computer processing starts entering the equation – as it does with bionic retinal implants – such fantastical applications suddenly become more possible.

The cameras used in such bionic systems could, in theory, capture different portions of the light spectrum, which could deliver super vision.

Moreover, smartphone makers are already using machine learning to improve what their devices’ cameras can see. The same artificial intelligence could be applied to bionic eye implants.

“Once you have a computer inside the eye … I see this being way more than envisioned,” says Flavio Rezende, a surgeon and chief clinical officer for iBionics. “Once you learn how to speak with the brain and the visual cortex, you can start sending all sorts of information, not just vision.”

It’s not yet known if technology can restore even full regular vision to blind people, but there’s no harm in thinking about future possibilities.

“It’s a little bit too early to be talking about Geordi La Forge,” the super-sighted visor-wearing character from Star Trek: The Next Generation, says John Zelek, co-director of the Vision and Image Processing Lab at the University of Waterloo. “But it’s baby steps, right?”