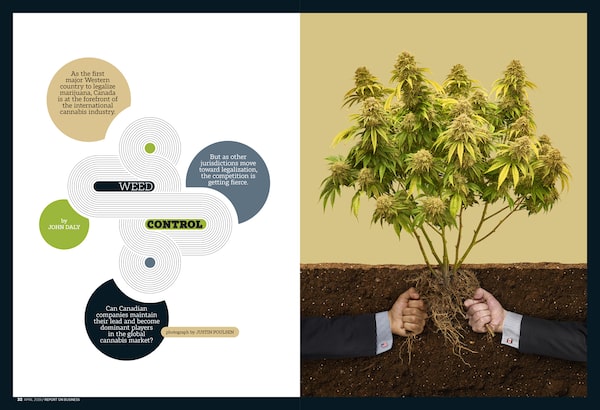

Justin Poulsen/Globe and Mail

The CEOs of just about all of Canada’s leading cannabis companies now have really big things to show off. In the case of Canopy Growth Inc., the largest publicly traded weed company on the planet, the boxy clump of windowless 1960s industrial buildings near the Rideau River in Smiths Falls, Ontario, that houses its headquarters and main processing plant still doesn’t have the wow factor of, say, the Googleplex in Silicon Valley or Elon Musk’s Gigafactory in Nevada. But as you drive closer, the continuing transformation of the old Hershey Co. chocolate factory that Canopy bought in 2013 gets more impressive. The intense weed smell is the first surreal thing to hit you when you get out of the car. Canopy has now renovated the entire 470,000-square-foot factory. Across the street, cranes are at work on a new 150,000-square-foot bottling plant for cannabis-infused drinks, which will become legal in Canada’s second wave of legalization of marijuana for recreational use this October.

Inside the main complex, the smell gets even stronger, and to anyone who has only seen pot in a small Ziploc bag or a plastic bucket in a black-market dispensary, the quantities are also surreal. There are 47 grow rooms, with hundreds of plants that yield an average-sized crop of 65 kilograms of flower five or six times a year. A one-kilo clear plastic bag of buds is roughly the size of a pillow, and the entire factory now produces more than 15 tonnes of cannabis a year. There are three machines that roll 1,800 joints an hour and an encapsulation room that produces 37,000 gel caps an hour.

A window in one hallway looks into a secure research lab, where two dozen scientists wearing blue coats, goggles and orange gloves are developing drinks, hard pills, edibles and other products that aren't yet legal in Canada. In the middle of the complex, workers are installing machines to make cannabis-infused chocolate.

There's also a visitors' centre that opened last August, with exhibits that review 5,000 years of cannabis history, and a Tokyo Smoke café, a cannabis-themed chain Canopy bought last summer. Just about the only thing you can't do is actually buy weed, because of Ontario's still-restrictive rules on retailing recreational cannabis.

“Remember, this is just No. 5,” Canopy chairman and CEO Bruce Linton boasts later in his dark cubbyhole of an office.

The Smiths Falls factory is Canopy's main processing plant but only its fifth-largest grow operation. The biggest is a 1.3-million-square-foot greenhouse complex in the Vancouver suburb of Langley.

Of course, Canopy’s largest Canadian competitors also have huge facilities of their own. Aphria Inc. has vast greenhouses in Leamington, Ontario, the tomato-growing capital of Canada. Toronto-based Cronos Group Inc. is building a huge greenhouse in neighbouring Kingsville. Last fall, Edmonton-based Aurora Cannabis Inc. opened a new 800,000-square-foot glass-roofed growing and processing facility near the city’s airport, and it’s completing a 1.2-million-square-foot operation in Medicine Hat.

Linton and his rivals picture their Canadian headquarters as bases for global cannabis empires, and they sketch out grand visions of rapid expansion. Even though they've barely begun to tap the newly legal recreational market at home, they're using their first-mover advantage here to establish beachheads abroad. “It's not very often that you see Canada leading the creation of a brand new global industry,” says Aurora chief corporate officer Cam Battley.

But how realistic are those ambitions? A lot of lingering questions remain. Can Canadian producers build brands that are popular around the world? Will Canada remain a leader in cultivation and become a major exporter? Will Canadian stock markets remain a hot spot for cannabis listings? Can legal frameworks and professional expertise be exported?

Most important, is time running short? Much of Canada’s first-mover advantage is based on the Trump administration’s refusal so far to legalize cannabis nationwide in the United States. What do Canadian companies have to do to solidify their lead before the window of opportunity closes for them and another opens wide for U.S. giants?

Can Canadian companies create dominant global cannabis brands?

There's no Budweiser, Marlboro, Coke or Prozac of cannabis yet, or even a Tim Hortons. But Canadian companies think they have a real shot at creating consumer brands as big as those ones. They started building brands years before they had significant sales, and Olivia Mannix, co-founder and CEO of Denver-based marketing agency Cannabrand Inc., says the strategy makes sense. Corporate producers have to push beyond old stoner stereotypes to win over mainstream consumers and investors. “It's education about the product to prepare the market,” she says.

Under national rules for medical weed that took effect in 2014, the biggest producers all introduced brands that promoted wellness and fun, rather than a wicked high (Canopy with Tweed and Spectrum, Aurora with grand-sounding strains of flower such as Thor and Ambition and the CanniMed and MedReleaf families it acquired, and Aphria with Canadian-inspired names such as Mohawk and Champlain). “Once Grandma and Uncle Ted are using cannabis to manage arthritis pain, it isn’t nearly so scary,” says Aurora’s Battley.

Now the licensed producers are trying to extend some of those brands into the recreational market.

They've also introduced new ones with similar upscale images, such as Aurora's San Rafael '71 and Aphria's Solei.

By contrast, U.S. markets in states that legalized medical and recreational cannabis early remained fragmented for years. Producers and retailers still can't move product across state lines. “It's really difficult to expand nationally,” says Bethany Gomez, managing director of Chicago-based Brightfield Group LLC, a leading cannabis consulting firm. “You have to recreate your entire supply from one state to the next.” U.S. producers aren't allowed to export either, and retailers can't import from Canada.

The U.S. federal laws against cannabis have prevented multinational giants in alcohol, tobacco, and pharmaceuticals from investing in the sector, so they have turned to Canada for their first initiatives. Cannabis is a disrupter to those three industries, as well as consumer packaged goods, yet it also provides all four with alluring new international growth opportunities.

The inevitable big question: Isn't it just a matter of time before giants of pharma, booze, tobacco and consumer products take over Canada's early leaders or drive them out of business? Some say it's already happening.

Last August, New York State-based drinks conglomerate Constellation Brands, maker of Corona, Robert Mondavi Wines and more than 100 other brands, invested $5-billion in Canopy. In December, tobacco provider Altria poured $2.4-billion into Cronos. That month, British Columbia-based Tilray Inc. announced joint ventures with Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV, the world’s biggest brewer, and Swiss pharmaceutical leader Sandoz International GmbH.

Both Cronos and Canopy say they are still running the show from Canada. “It's all us,” Linton insists.

Canopy will develop, produce and market drinks itself. Constellation will provide money, advice on formulation, and expertise in branding and analytics. “We are their cannabis world,” he says.

Linton may be calling the shots today, but it's clear that Canopy's fate is now controlled from south of the border. Constellation has warrants, which, if exercised, would boost its stake in Canopy to over 50% from its current 38%. The alcohol company also has the right to nominate four of the seven board members, giving it effective control. Similarly, Altria has the option of boosting its stake in Cronos to majority ownership.

Even with deep-pocketed international investors, cracking into U.S. markets won't be easy for Canadian companies. Brightfield's Gomez and other analysts say that when federal legalization comes in the United States—something many expect to happen by 2021—Canadian brands will stand little or no chance of competing there.

That's because, despite the highly restrictive state-by-state rules, strong national U.S. brands have already emerged.

Among suppliers of vaporizers, “OpenVape has really nailed it and Pax has done really well,” Gomez says. “In topicals, Mary's Medicinals has done very well. In edibles, there's quite a few, like Kiva.”

There are multi-state retail chains as well, including three that went public on Canadian stock markets: Curaleaf Holdings Inc., Green Thumb Industries Inc. and MedMen Enterprises Inc. “It’s not as if there are huge companies in Canada and just mom-and-pop operations in the United States,” says John Hudak, a senior fellow with the Brookings Institution, who co-authored a study about the prospects for Big Marijuana in 2016.

Selection is another problem hampering Canadian brands.

So far, Canada's providers have only been allowed to sell dried flower, pre-rolled joints and low-potency oils. That has allowed them to build capacity at home and start distributing or producing in countries where medical cannabis is legal.

(Uruguay is the only other country where recreational cannabis is legal.) But the only big competitive advantage Canadian companies have been able to promote is the near-pharmaceutical quality of their products, says Steve Looi, director of origination for Toronto-based White Sheep Corp., a small producer that also invests in other cannabis companies.

Meanwhile, black market brands and unbranded products continue to flourish. Illegal suppliers have been providing a much wider and more potent range of products in almost every country for decades, and a lot of them are very good at it. In Canada, those products include gummy bears, hash oil, shatter (a hash concentrate) and others that still won't be legal even after the next phase of recreational legalization this fall. “Black market weed is still the best, unfortunately,” Looi says.

The legal selection is already far greater in many U.S. states. “We're tracking more than 400 different vape pens in California alone,” says Gomez. To compare Canadian and U.S. providers, she says, “go online and look at the Ontario Cannabis Store, and then look at the products that are available in any dispensary in Las Vegas.” The restrictive packaging mandated for recreational product in Canada also inhibits branding—much of the space on labels is taken up by health warnings.

Gomez and other analysts say that the best hope for Canadian producers is to continue to move into regulated foreign medical markets early.

That means signing deals with governments to become one of a small number of official suppliers to patients. In the United States, Gomez says, “it doesn’t make sense for them to try to sell a Canopy-branded flower or a Tweed flower. It makes more sense to pick up a U.S. brand that may have more awareness and more sophisticated branding.”

THE VERDICT: Canadian Tire’s push into the United States failed, Tim Hortons hasn’t made much headway, and BlackBerry ultimately flamed out. Global prospects for Canada’s leading pot brands look limited at best.

Will Canada become a global leader in cannabis cultivation?

It's a snowy January day in Toronto. Pick up the phone and ask Anna Shlimak, Cronos's head of investor relations and communications, if it makes sense to grow cannabis in Canada, and she laughs, pauses and then delivers a very deft response: “From a geographical climate perspective, no.”

But as Shlimak and other industry executives explain, there are many other factors that influence where they grow cannabis and how much.

One of the biggest so far has been politics. Governments that want to legalize cannabis also want to regulate and tax it, and create jobs and other economic benefits. This means that Canada's biggest producers will likely continue growing and processing large amounts here.

There are economies of scale in growing indoors and processing, which is why most of the big producers raced to buy or build huge greenhouses and factories in advance of recreational legalization in Canada. In doing that, Canopy and others also looked to save money and win support from municipalities by locating in depressed areas. “That's why we love Smiths Falls and Yorkton, Saskatchewan, and empty greenhouses in Niagara-on-the-Lake,” Canopy's Linton says.

But in expanding globally, executives say they won't be exporting much from Canada. Broadly speaking, growing in greenhouses is cheaper than growing under artificial light in factories, and growing outdoors in warm climates can be even cheaper than greenhouses. Linton and other executives also doubt that governments will permit a large-scale international trade in cannabis any time soon.

Combine politics and economics, and cannabis will likely be produced and distributed within countries or regions in the early years after legalization. “We plan to be your local producer,” says Cam Battley of Aurora, which is now active in 22 countries.

All of Canada's biggest producers have moved fast to set up foreign growing and distribution operations, mainly through joint ventures. Medical cannabis became legal in Germany in 2017, for example, but the country had no large-scale production of its own, so Canopy, Aurora, Aphria, Cronos and Tilray quickly established local operations and began exporting there.

The trans-Atlantic shipments won't last, however. Denmark allowed bulk exports beginning this past January, making it a front-runner as a production hub for the European Union. Canopy, Aurora and Aphria had already formed joint ventures to produce there.

Tilray chose a different entry point. It set up outdoor growing fields, greenhouses and a factory in Portugal in 2017. Cronos established a joint venture in 2017 with Kibbutz Gan Shmuel in Israel, which will be able to ship to Europe. All five of those Canadian producers have already established beachheads in Australia and Latin America, as well.

The United States also beckons, of course—though there, too, it's easier to set up separate operations or partner with local growers, rather than exporting from Canada. Linton points to Canopy's reaction to the Farm Bill that President Donald Trump signed into law last December.

The bill legalized the growing of hemp. Hemp yields CBD—which is non-psychoactive, and has health and wellness applications—but not THC, the stuff that gets you high. Three weeks later, Canopy announced it planned to spend up to $150-million (U.S.) to build a hemp industrial park in New York State and lauded New York Senator Chuck Schumer, who pushed hard for the bill.

Over the even longer term, prospects for growing cannabis in Canada appear to be limited at best. “We've always looked at this industry from a global perspective,” says Tilray CEO Brendan Kennedy. “Cultivation will migrate south, closer to the equator.”

THE VERDICT: Canada will have a healthy market for locally grown cannabis, but we won’t be a big exporter. However, Canadian companies will have substantial cultivation facilities abroad.

SIDEBAR

Many cannabis companies are tapping into international and homegrown celebrities to boost their brands. Seen above, clockwise starting left:

- When drug-and-booze-free Kiss bassist Gene Simmons became a partner in B.C. cannabis company Invictus, it changed its stock ticker to GENE

- Newstrike Brands Inc., the parent of Up Cannabis, is partially owned by members of the Tragically Hip

- Atlantic Canadian hash lovers the Trailer Park Boys have a branding partnership with OrganiGram Holdings Inc.

- Snoop Dogg has a partnership with Canopy Growth and has made venture investments in vape hardware company Green Tank Technologies and cannabis inventory platform Trellis

- Cooking and decor guru Martha Stewart is developing a new line of products with Canopy Growth

- Kevin Smith and Jason Mewes, who played pot dealers Jay and Silent Bob in various movies and TV shows, have a licensing deal with Beleave Inc.

- Noah “40” Shebib, co-founder of Drake’s OVO Sounds, recently co-founded cannabis company BLLRDR

Will Canada remain a global hub for cannabis stock listings?

Three years ago, MedMen was a cannabis dispensary in West Hollywood with a small growing operation in nearby Sun Valley, California. Last May, it went public on the Canadian Securities Exchange (CSE) in Toronto through a reverse takeover of a shell company and raised $143-million, giving it an implied enterprise value of more than $2-billion.

Dozens of other new Canadian and U.S. cannabis companies have also hit the jackpot on Bay Street over the past five years. Canadian stock markets—the TSX and its Venture Exchange, and the smaller CSE—have become the hottest cannabis venues in the world. According to data from New York-based Viridian Capital Advisors, which specializes in cannabis financings, public and private cannabis companies raised $14-billion (U.S.) worldwide last year, four times the total for 2017. Of that, almost two-thirds was raised by Canadian companies.

That surge has also brought notoriety. There are still plenty of mainstream portfolio managers and analysts who dismiss the boom as a bubble. And many American companies have trekked north to raise money because they couldn't conform to U.S. federal law and the listings requirements of American exchanges.

Yet, in many ways, that notoriety has helped midtier Canadian investment dealers become leading players in global cannabis finance. Canada’s Big Five banks and Wall Street’s largest dealers wouldn’t touch cannabis for years, and are now arriving late to the game. According to a ranking by Dealogic, a London-based global provider of financial data, in 2018, three of the top five firms in cannabis mergers and acquisitions worldwide were Canadian, led by early cannabis backer Canaccord Genuity. It was also the top firm in cannabis IPOs, followed by BMO Capital Markets, the first of the Big Five to embrace the sector. But Dealogic’s rankings also show that several Wall Street firms are catching up, including established giants Goldman Sachs and Lazard Ltd.

Is Bay Street's lead in cannabis sustainable? History offers some encouragement. Canadian stock markets were established in the late 19th century in large part as forums for mining companies to raise money. Many of the smaller issues were and still are sketchy, and Bay Street has been tarnished by plenty of mining scandals over the years. Since 2000, much of Canada's mining industry has been hollowed out, as giants such as Noranda and Inco were swallowed by foreigners. Even so, in 2017, 59% of global mining financings were done on the TSX or the Venture Exchange.

Tilray's Brendan Kennedy, however, is skeptical that Canada can remain a centre for cannabis financings. He created a sensation in the industry last July when he took his company public not in Toronto, but on Nasdaq. U.S. markets would not allow suppliers who did business in violation of federal law to list, but they have allowed Canadian companies with no U.S. operations, like Tilray.

It was the hottest cannabis IPO of the year. The company raised $153-million (U.S.) by selling a minority stake at $17 (U.S.) a share. The stock then skyrocketed to a peak of $300 (U.S.) one day in September. Tilray briefly surpassed Canopy, which has a market cap of about $16-billion, and established corporations like Barrick Gold Corp.

Since then, Tilray's share price has drifted back and levelled off around $70 (U.S.).

Kennedy deliberately steered clear of Toronto to raise money. He says Bay Street's cannabis market now seems to be dominated by speculators, rather than savvy and patient institutional investors.

Watching Toronto's pot stock boom from a distance—Kennedy is based in Seattle, and commutes to Tilray's Nanaimo, B.C., headquarters by plane—he's felt alarmed. “Frankly, I was surprised so many Canadian companies went public so early on the TSX,” he says—at an earlier stage in their development than new companies in Silicon Valley.

Kennedy also thinks the boom is turning into a zero-sum game. New investment is drying up, which will slow deal flow, and investors already in the game are trading among themselves. He expects more leading cannabis companies will shift south to raise money.

U.S. markets offer natural advantages, such as the opportunity to pitch to more blue-chip portfolio managers. Another point in favour is being regulated by Washington’s Securities and Exchange Commission, rather than a patchwork of Canadian provincial regulators.

While cannabis companies that do business in violation of U.S. federal prohibition can't raise money there using the Wall Street banks, new laws making their way through Congress are expected to lower and in some cases even eliminate those hurdles. The Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act, as well as the Strengthening the Tenth Amendment Through Entrusting States (STATES) Act, have support in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, and are expected to pass both chambers of Congress at some point before the end of the decade. Asked whether such legislation would slow the rapid pace of American cannabis companies going public in Canada, GMP Securities analyst Martin Landry said, “Yes, absolutely—they would dry up overnight.”

So, does this mean Bay Street's window of opportunity for becoming a global cannabis financial hub is closing? “I think it's already closed,” Kennedy says.

THE VERDICT: Once legislative changes make it easier for cannabis companies to list in the U.S., new foreign listings in Canada will dry up.

A soft power in cannabis

If you’re a flag-waving Canadian, you might feel a bit disappointed to hear that we are unlikely to build giant global cannabis brands or export mass quantities of our bud around the world. The Toronto pot-stock boom may indeed run out of gas soon, as will the lucrative spinoffs that go along with it. But that’s no reason to cry into your foreign-controlled Molson or Labatt beer.

National legalization of medical and recreational cannabis gave Canadian companies a lock on the domestic market and a real head start abroad.

Many countries are adopting similar rules, and Canada will continue to have outsize influence in the regulatory and political worlds as more jurisdictions examine the Canadian model. Already, Canada has seen visits from Mexican government representatives and shared information with several U.S. state governments. Our experts and consultants are also uniquely qualified to help other countries set up cannabis markets.

“You have national acceptance and a regulatory framework that can be followed around the world,” says White Sheep CEO Hamish Sutherland. Prior to founding his own company, Sutherland was chief operating officer of Bedrocan Canada, one of the first big licensed medical producers in Canada, which Canopy bought in 2015. These days, he's spending a lot of time in Australia and Lesotho, advising on the construction of two huge growing and processing facilities.

Sutherland argues that Canadian consultants and companies will benefit if other countries continue to open up their legal cannabis markets in similar ways to what Ottawa did. This would give Canadians time to keep replicating abroad what they have done at home. For the moment, he says, “We have such a lead, no one else can touch us.”

Our cannabis companies might not be destined to be global giants, but we are still likely to punch above our weight on the world stage.

With files from Mark Rendell and Jameson Berkow.