If you cast your mind back to the hottest brands and stars on the planet like it’s 1999, you’d salivate if you could own the rights to even some of those names. In fashion retail, Brooks Brothers was on a roll, Juicy Couture had just been founded and was about to design its iconic tracksuit for Madonna, and Ted Baker and Forever 21 had hit their stride.

In sports, two dominant stars of their era, David Beckham in soccer and Shaquille O’Neal in basketball, were in the prime of their playing careers. Chronicling their exploits and those of other champions, Sports Illustrated was still a thriving weekly magazine and one of the principal properties at the centre of the blockbuster merger of Time Inc. and Warner Communications.

In the world of entertainment, even though Marilyn and Elvis had died decades before, they were arguably bigger stars than they had been when they were alive. They’d achieved iconic status.

Those names—and more than 50 others—are now owned or co-owned by a New York–based juggernaut called Authentic Brands LLC that’s led by two Canadians: founder, chairman and CEO Jamie Salter, and president and chief marketing officer Nick Woodhouse. And that iconic status is at the centre of Authentic’s business model.

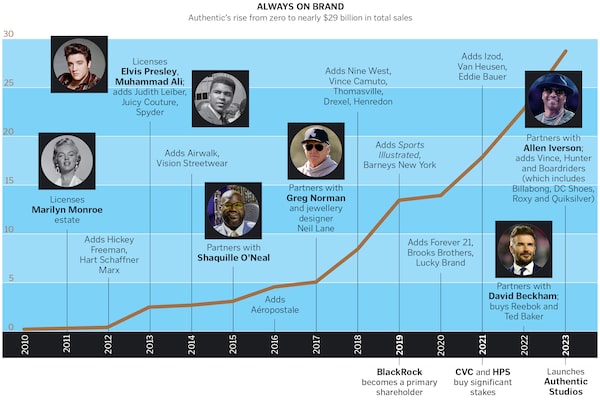

Salter launched the company in 2010 and hired Woodhouse the following year. With just 11 employees at the start, Authentic’s brands had about $100 million worth of retail sales in 2010. By 2022, that total had reached $23 billion in annual retail sales. (All currency stated in U.S. dollars.) All that money doesn’t flow to Authentic, of course, which is still privately owned. The bulk of its revenue comes from licensing the brands, and the prospectus for an aborted 2021 Authentic share issue disclosed that it took in $489 million in revenue in 2020 and earned a fat $225-million profit, in a year when the brands did $14 billion worth of business.

Authentic won early headlines in 2011, when it acquired Marilyn Monroe’s estate. Wall Street took more and more notice over the 2010s as the company led acquisitions of brands such as Aéropostale and Nine West, Shaq partnered with Authentic in 2015, and money managers General Atlantic (in 2017) and BlackRock Inc. (in 2019, and at $9.1 trillion in assets under management, the world’s biggest kahuna) invested in Authentic. The company then accelerated its acquisitions, usually made with partners, during the COVID-19 pandemic—the biggest to date being the $2.5-billion purchase of Reebok in 2022. Right around that time, Beckham signed on, as well.

To hear Salter, 61, tell it, Authentic has built a unique and truly global platform for revitalizing brands, with the help of a network of 1,500 licensees in 150 countries. “It used to take us three to four months to innovate a brand,” he says from his cottage in Muskoka, where he spends a few months a year and occasionally hosts celebrity guests, such as Beckham and his family. Now, “literally within 30 days, we are running hard all over the world.”

For skeptics, however, Authentic is a bit like a landlord who has invested in and refurbished several established marquee buildings in the hope that they’ll continue to provide steady income in the future. If you get stellar tenants like Beckham, great. But if you get into a nasty legal dispute with one of them, watch out. Which is one way of looking at Authentic’s battle with Arena Group Holdings, one of its licencees, over the future of ailing Sports Illustrated, a brawl that spilled out into public view in January.

There are risks and rewards with any strategy. Whatever your view of Authentic’s fundamental business model, or prospects for individual brands and celebrities in its portfolio, its expansion is undeniable. And the company looks like it has enough momentum to continue for the rest of the decade, and quite possibly beyond. But Salter and Authentic will have to contend with some potential bumps in the road, as well—big ones.

How did two Canadian guys, one born in Toronto and one in Oshawa, end up partnering and hobnobbing with some of the world’s biggest names in retail, sports, entertainment and finance? The short answer is that Salter and Woodhouse both paid a lot of dues over three decades.

Salter started out small in sporting-goods marketing in the 1980s, quickly tapping into the surging popularity of snowboarding, then still almost an outlaw sport. In 1992, he joined forces with two Seattle entrepreneurs to found board manufacturer Ride Inc., a Nasdaq wonder that went public in early 1994 and saw its share price shoot up by about 1,500% within 18 months, then plummet thanks to slower-than-expected growth. Salter stepped down as CEO in 1996.

Leah den Bok/The Globe and Mail

After several other sporting goods–related ventures over the next decade—successful ones—Salter and Hilco Trading, a privately owned American firm, founded Hilco Consumer Capital in 2006.

Hilco Consumer Capital was and is essentially a liquidator—it swooped in and bought troubled or outright bankrupt brands, then tried to revive them with new licensing deals and partnerships. Under Salter, it bought, polished up and sold off several brands: furniture retailer the Bombay Co., and the Tommy Armour and RAM golf equipment lines. It wasn’t ultimately successful with two others: Polaroid and Halston.

Salter was tight-lipped about why he left Hilco in 2010, and he praised the company afterward. Now, whatever it may take to co-ordinate Authentic’s more than 400 employees, its licencees, brand executives and celebrity partners, and the handful of large investors that own the company, one big attraction for him still seems to be that he’s ultimately the guy in charge.

In many respects, Salter has also turned Authentic into a family business. The Salters are a substantial shareholder, although down the food chain from BlackRock, which has the largest stake at about 25%. And all four of Salter’s sons work for the company. Corey, who’s 35 and now chief operating officer, says it’s always been hard to get through a full family dinner without discussing business.

He grew up in the Forest Hill neighbourhood in Toronto and recalls his father bringing home sporting goods catalogues for upcoming seasons, for items like snowboards and skateboards. Corey and his brothers would be “allowed to circle 10 products each, and the 10 most circled got picked.”

Woodhouse, who’s now 55, also has a background in sporting goods, and he worked his way up through the Forzani Group (which owned Sport Chek and other chains)—from selling in a store in Fort McMurray in 1986 to vice-president. “I’ve known Jamie for over 30 years,” Woodhouse says. “I was a buyer, and he was a seller.”

Now working and living in Miami with his wife and two young children, Woodhouse remembers Fort McMurray winters well. “Minus 54 degrees and a wind chill of minus 61,” he says. “It gets light around 9:45 and dark around 2:15. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” And he recalls long car drives through Saskatchewan and Manitoba as a regional rep: Estevan, Flin Flon, Moose Jaw and other far-flung towns. Woodhouse later worked in Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver.

Around the time that Forzani was negotiating its sale to Canadian Tire in 2011, Woodhouse and his future wife bumped into Jamie and Corey Salter on a flight to an Ultimate Fighting Championship bout in Nassau. They talked about joining forces, and within a few months, Woodhouse had moved from Calgary to New York. “Jamie was a successful entrepreneur prior to Authentic. I’d always worked for a company,” Woodhouse says. But their relationship soon evolved into “can’t do it without the other one,” he says. And that trust has lasted.

If you want to get a bit of rise out of Salter or Woodhouse, plus a patient and deft explanation of what Authentic does, suggest that its basic business is buying beat-up brands and then trying to squeeze more revenue out of them. “Undervalued, undervalued,” Salter insists, and the explanation begins—several of them, actually.

He and Woodhouse both use the phrase “secret sauce” when describing the basics of Authentic’s platform, and they’re referring to the company’s network of 1,500 partners around the world. When Authentic buys a new brand, it typically lines up several partners to take on a licence, and the company can work on several deals at once. “We don’t have to renegotiate with that partner,” Salter says. They can quickly hammer out basics such as a marketing plan and a guaranteed minimum royalty rate that licencees will pay to Authentic. “It’s not like we have to retrain them,” he says.

Salter cites Authentic’s acquisition of the intellectual property of Britain’s Hunter Boot, maker of the classic Wellingtons, for an estimated $125 million last June. Hunter had fallen on hard times in recent years, but it was still respected and had outdoor wear and luxury lines, and Authentic could integrate the new asset quickly.

Salter and Woodhouse also point out that while Authentic gets plenty of publicity for signing Beckham, Shaq and other celebrities, its roster of them is a small and exclusive group. The company’s other “living legends,” as it calls them, are retired basketball greats Allen Iverson and Julius (Dr. J.) Erving, champion golfer and now LIV Golf Investments CEO Greg Norman, Mexican singing sensation Thalia Sodi and high-end jewellery designer Neil Lane. Authentic’s stable of what it calls “icons” is even smaller—just three mega-names: Marilyn, Elvis and Muhammad Ali.

“It’s different from an endorsement deal,” Salter says. Authentic basically works with celebrities to advance mu-tual interests—a true partnership. “We get calls from lots and lots of famous people to partner with us,” Woodhouse says. “We’re very selective.”

Lauren Beitelspacher, a professor of marketing at Babson College in Massachusetts, whose research interests include buyer-supplier relationships, retail management and retail supply chains, said she’s impressed by Authentic’s brands, its licensing model and its overall strategy. “Brands that enjoyed success in the ‘80s, ‘90s and early 2000s kind of kept riding that wave and didn’t adapt to the changing consumer model,” Beitelspacher says. “By the time they realized they needed to change, it was too late, and they were stuck playing catch-up.” Some brands Authentic has bought had fallen out of favour, but they were still well known to consumers. “There’s already built-in brand equity there,” she says. “And ambivalence is much easier to deal with than dislike.”

Beitelspacher also agrees that some brands need some streamlining and modernization to be reinvigorated. “Because Authentic has this big buying power, that allows them to invest in infrastructure to streamline operations,” she says. “The No. 1 way to reset your margins is to streamline your operations and get your inventory under control. That isn’t super sexy for consumers, but it is really sexy to investors.”

She uses Ray-Ban as an example. Presidents wore its sunglasses, and so did Tom Cruise and other stars. But by the 1990s, “they were over-inventoried and sold in gas stations.” In 1999, Italian giant Luxottica Group bought Ray-Ban from its parent, Bausch & Lomb, pulled the sunglasses off the market, shifted the brand upscale, streamlined operations, “and now it’s successful,” Beitelspacher says.

As Authentic expanded in 2010, it bought bigger and bigger names, including suit maker Hart Schaffner Marx in 2012, Aéropostale (as part of a consortium) in 2016, Nine West in 2018 and Barneys New York in 2019. Among celebrities, living and deceased, the company added Shaq, Greg Norman, Elvis and Ali.

The company also impressed investors on Wall Street and beyond by showing them, as Woodhouse says one partner put it, that it could “add zeroes and commas” to its deals. In 2017, private equity giant General Atlantic invested in Authentic for the first time (by 2023, the firm had put in a total of $2 billion through various initiatives). And in 2019, BlackRock made a $875-million “strategic investment” in Authentic.

But then the pandemic arrived and rattled just about everyone.

Part of Salter’s MO is asking big, fundamental questions like, “Is the brand a bad brand?” If it just has the wrong structure or it’s over-levelled, maybe it’s worth pursuing. And when COVID hit North America in March 2020, Salter says, “Let’s be honest: I panicked.” At first, he thought the world was going to end.

But after talking with Woodhouse and various others, he calmed down and decided what to do next. “If it ends, we’re out of business anyway,” he says. “If not, I’m going to become very, very wealthy. Let’s go raise money, and let’s go out and buy lots of brands.”

The rapid-fire series of acquisitions, usually with financial partners, won Authentic a lot of publicity. They included Forever 21, Brooks Brothers and Lucky Brand in 2020; Eddie Bauer, Izod and Van Heusen the following year; and Reebok (the biggest addition to date) and Ted Baker in 2022. Among celebrities, Authentic landed Beckham in 2022 and signed an agreement to help Iverson develop his brand early last year.

The expansion drive didn’t pay off right away. Salter says 2020 was the only year since 2010 that Authentic’s organic growth (expansion of existing operations) was negative—albeit just -1%. And he and other top managers took pay cuts. But overall, he says, “I can tell you COVID was good for us.”

Corey Salter also says there were bad and good aspects of the pandemic. “Obviously sales were down everywhere,” he says. “Companies had to go through a lot of things, and that created a lot of opportunities for us.” But hiccups and challenges remain. Forever 21, for example, has fewer stores than it used to, but still about 400 in the United States. With several chains, Corey Salter says, the company “learned to retain U.S. stores, retain talent.”

Beitelspacher agrees that the pandemic caused some big upheavals in retail, but some fundamental principles still apply. Even brands that are now successful online should retain stores, she says. “They might not be profitable, and it might be an operational challenge, but it’s a way to get customer feedback on inventory in real time.”

There was also a big financial distraction for Authentic during the pandemic. In July 2021, it filed for an initial public offering. But in November, it pulled the offering and said it would instead sell equity stakes in the business to private equity firm CVC Capital, hedge fund HPS Investment Partners and a group of Authentic’s existing stakeholders.

As of last summer, Salter says Authentic’s six largest shareholders were BlackRock at 25% (the only number he’d give out), General Atlantic, CVC, the Authentic executive team, HPS and long-time backer Leonard Green & Partners. Salter and Woodhouse seem quite happy to stay private. “We don’t need to go public. We’ve never needed to go public,” Salter says. Woodhouse agrees: “You give up a lot when you go public. I’d say it’s 50-50.”

And occasionally, if you do enough deals, you just hit the jackpot. That’s certainly been the case with Beckham, 48. Now soaking in endorsement deals and various business ventures, virtually everything he and his wife, Victoria, touch seems to turn into money, including the blockbuster Netflix biography of the couple last year. Woodhouse is proud that Authentic had a stake in the production company. “When you see the true story, it’s hard to duplicate that, right?” he says.

But after a big winner, there’s often a big loser.

Sports Illustrated is certainly an iconic brand, and its annual swimsuit edition—for one—continues to generate scads of publicity every year. But in many respects, it’s also been in decline for decades. The magazine cut back from weekly to biweekly publication in 2018, and then to monthly in 2020.

Authentic bought Sports Illustrated for $110 million in 2019, in the hope of making it a pillar in a new “media vertical” for the company. “Sports Illustrated has real heritage, authenticity and respect,” Salter declared. “It’s hard to get all those in a single brand.”

But, as Authentic often does, it turned around and licensed Sports Illustrated to another company, Arena Group, which was supposed to pay Authentic $15 million a year for the publishing rights. On Jan. 5 of this year, Arena Group disclosed in a securities filing that it had failed to make a $2.8-million loan payment and a $3.75-million quarterly licensing payment due to Authentic at the end of 2023.

The dispute quickly got worse—a lot worse. The Arena Group’s executive suite was already in disarray. The company had fired CEO and Sports Illustrated publisher Ross Levinsohn in December, following a scandal triggered by a report in Futurism, an online tech publication, that Sports Illustrated had published articles by fake, artificial intelligence–generated writers.

The two companies then started playing hardball with each other, and with the magazine and its staff. In another securities filing, Arena Group said Authentic had yanked its licence and hit the company with a $45-million charge for violating their original agreement. On Jan. 18, Arena Group issued a release announcing a “significant reduction” in Sports Illustrated’s workforce of more than 100 employees.

In an interview with The Washington Post the following day, Salter talked tough.”If a company doesn’t pay me, I breach,” he said. He also told the Post that Manoj Bhargava, the founder of 5-hour Energy, Arena Group’s largest shareholder and the leader of its strategy, had sought to lower the licensing fee. “He’s trying to negotiate with me, and I told him to f--- off. He tried to change the agreement. When you sign a deal with us, you live by the deal.” Salter added that he might sell the licence to other interested parties. Levinsohn, in turn, resigned from Arena Group’s board, saying the destruction of the Sports Illustrated brand and its newsroom is “one of the most disappointing things I’ve ever witnessed in my professional life.”

Early the following month, two staffers from Authentic contacted Report on Business to ensure that we were aware of the proper context surrounding the Sports Illustrated dispute. But on the record, though, they stuck with the statement Authentic had issued the previous month. “Authentic is here to ensure that the brand of Sports Illustrated, which includes its editorial arm, continues to thrive as it has for the past nearly 70 years. We are confident that going forward the brand will continue to evolve and grow in a way that serves sports news readers, sports fans and consumers. We are committed to ensuring that the traditional ad-supported Sports Illustrated media pillar has best-in-class stewardship to preserve the complete integrity of the brand’s legacy.”

Whatever the fate of the magazine, the Sports Illustrated brand still has lustre. On Super Bowl weekend in Las Vegas, Authentic went ahead with a lavish theme party at the XS Nightclub the night before the big game. Guests including Justin Bieber, Kim Kardashian, Tiffany Haddish and many more strolled down a red carpet lined with classic magazine covers featuring the likes of LeBron James, Serena Williams and a screaming Tiger Woods. “Vegas was epic,” Salter told the Post. Reading reports about the party, Lauren Beitelspacher, the marketing professor, was impressed, too. “They had all these celebrities, and they were showcasing all of the other brands that they work with,” she says. “I thought it was really slick.”

Indeed, but possibly not the best optics in a crisis. As of late February, the Sports Illustrated dispute remained unresolved. The magazine was still running stories on its website, but morale among remaining staff was reportedly low. On Feb. 27, the employees’ union issued a release commenting on news reports that Authentic was considering a deal that would let Arena Group keep operating Sports Illustrated, but “gut our staff and eliminate our union. If this comes to pass, then it would represent the true death of SI.”

One big lesson the pandemic taught, Beitelspacher says, is that companies have to have a disaster strategy to survive and push beyond sudden catastrophes. When the dust from the blow-up over Sports Illustrated settles, Salter might want to work on that.

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.