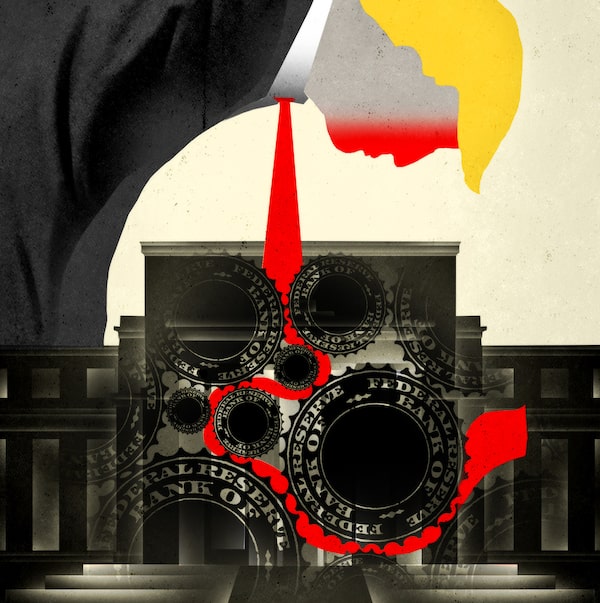

brian stauffer

Global markets breathed a sigh of relief when U.S. President Donald Trump tapped Jerome Powell, a former Treasury official and investment banker, to take the helm of the world’s most powerful central bank last February. That tends to happen when the unpredictable White House occupant does something rational. And the appointment of Powell, who was already sitting on the Federal Reserve Board as an Obama appointee, certainly qualified.

Today, the markets shudder every time Trump fires another broadside at the Fed and its moderate chair. He has been doing so with growing vitriol, excoriating the bank for spooking investors, undermining his efforts to boost economic growth and foolishly relying on data instead of listening to him.

When stocks plunged, Trump blamed the Fed. When the cost of financing the massive public debt shot up, he blamed the Fed.

When General Motors revealed plans to close some plants and lay off workers, he blamed the Fed.

It’s surprising he hasn’t blamed Powell – at least, not yet – for the California wildfires, the Chinese trade war or his party’s midterm election drubbing.

“I'm doing deals, and I'm not being accommodated by the Fed,” Trump whined to The Washington Post in late November. “They're making a mistake, because I have a gut, and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else's brain can ever tell me.”

He lashed out again after the Fed had the temerity to ignore him and nudge its target rate up by another quarter point in December, to a range of 2.25% to 2.5%, which remains dovish by historical standards. Powell pointedly remarked, “Political consideration plays no role whatsoever” in the bank’s interest rate decisions.

Still, the unusual presidential assault on the central bank for pursuing a sensible course of gradual monetary tightening sparked fears it may not be able to maintain its essential independence from political interference in the Trump era and beyond.

Without that assurance, currency, debt and equity markets will rightly wonder whether the Fed can continue crafting credible policies, especially in a crisis. Such uncertainty comes on top of deepening worries about the impact of Trump's ill-conceived trade actions, his renewed Iran sanctions, fiscal pump-priming and a soaring budget deficit.

Perversely, if the markets started believing Trump’s bluster would actually tempt the Fed to pause or reverse direction in 2019 – it’s signalling there will still be a couple more hikes – inflationary expectations would rise. That would force the bank to respond with more aggressive tightening, which would really trigger a presidential tweet storm.

During the global financial meltdown a decade ago, the Fed boldly experimented with previously untested weapons in its arsenal – slashing short-term interest rates to near zero, snapping up troubled mortgage assets and pumping trillions into the financial sector.

Those actions stabilized a tottering financial system and helped prevent a crippling depression.

Ben Bernanke, the Fed chief who led the rescue, faced criticism from conservative lawmakers who feared (wrongly) that easy-money measures would ignite inflation and shred the currency.

Bernanke remained unfazed, insisting interest rates and the Fed's ballooning balance sheet would get back to normal once the emergency measures were no longer needed. That process finally began in late 2015 under his successor, Janet Yellen. And it has continued on Powell's watch.

The Bank of Canada, which is coping with stronger economic headwinds, has been moving more slowly on a similar trajectory.

The aim is to reach a “neutral” level, where rates have neither a positive nor a negative economic impact. Both central banks bristle at any hint that politics play a part in their decisions.

“My focus is on essentially controlling the controllable,” Pow-

ell said in October. The Fed, he insisted, is “quite removed from the political process.”

The question is whether it can remain that way in a hyperpartisan Washington. And what happens if the monetary minders respond too slowly or too aggressively to changing circumstances merely to assert their independence?

William McChesney Martin once described his role at the Fed as taking away the punch bowl just when the party was heating up.

His decision to do just that as inflation crept up in late 1965 sparked a behind-the-scenes row with President Lyndon Johnson. An enraged Johnson, who was dealing with the skyrocketing costs of the Vietnam War, shoved Martin against a wall at his Texas ranch.

“Martin, my boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won't print the money I need,” Johnson fumed.

A shaken Martin, who had been at the helm of the Fed since 1949, wouldn't budge; but when inflation later surged, critics suggested the bank had reacted too slowly.

It's no secret why most politicians dislike rising rates: They hit spending, boost financing costs and anger voters, especially those carrying a lot of debt. Still, the long-standing presidential custom has been to stay mum on Fed policy—at least until Trump came along, looking for a convenient scapegoat for times when his “gut” leads him astray.

Candidate Trump decried the bank's ultralow rates when he was on the campaign trail. Now, he aims his barbs at his hand-picked choice to continue reversing those policies, even as he makes the Fed's job tougher through protectionist tariffs, tax cuts and tweets.

Whatever sane advisers remain in the White House need to remind their boss that he can’t fire Powell over a policy rift, but that his words matter to nervous markets. So unless Trump is eager to see what a full-fledged panic looks like, he would be wise to avoid even the appearance of meddling in the Fed’s affairs.