There are two things you should know about Connor Teskey’s philosophy for investing in the climate transition.

Teskey is head of the rapidly growing renewable energy arm of asset management giant Brookfield, and his first rule is that he accepts no discount on investment returns simply because Brookfield’s decarbonization goals could be good for the planet. When sifting through the scores of potential deals that cross his desk, Teskey is looking for a target return of 12% to 15%. “This investment strategy is 100% commercial,” he says, “and we think that is incredibly important.”

The second thing you should know is that, from time to time, Brookfield will cast its gaze past investment opportunities that are “already green and clean and pristine,” Teskey says. Instead, it makes big investments in heavy emitters to help them start the process of turning over a new leaf. It’s a strategy of investing “to drive material decarbonization” where emissions are most acute. “We actively seek opportunities where those two things are completely aligned,” he says via video call from Brookfield’s London office, where he’s based. “We don’t ever want to be accused of, are you trying to make money or are you trying to save the world?”

Why not both? In 2021, Teskey’s division launched its first, $15-billion Brookfield Global Transition Fund, the largest pool of private capital earmarked for funding the transition to net zero (all figures in U.S. dollars). Brookfield raised the money—including $2 billion of its own—and deployed the entire fund into 19 investments, all in two years.

One of those deals saw Brookfield lead a $10.5-billion consortium bid to take over Origin Energy, an Australian power generator that produces energy from natural gas–fired stations and coal plants. If the deal closes—it faced an uncertain shareholder vote in late November—Brookfield has pledged to reduce Origin’s carbon emissions with as much as $12.5 billion of investment in renewable power generation and storage, which could allow the company to retire one of Australia’s largest coal-fired plants. If the plan works, Brookfield claims it could contribute up to 8% of the reductions Australia needs to hit its national carbon emissions targets for 2030.

And if Brookfield is able to achieve the decarbonization goals it has set for all 19 of its investments through its first Transition Fund, the company says it would avoid emissions equivalent to the output of London, New York and Singapore combined. “This is not immaterial,” says Teskey. “The scale of what we’re doing, the level of deployment, the level of decarbonization is very meaningful.”

Editor’s Note: For every step forward, it seems women take two back

Newcomer of the Year: How Tracy Robinson got CN Rail back on track

Innovator of the Year: Hopper’s Fred Lalonde went from hacker to tech titan

Teskey, who turned 36 this fall, started at Brookfield 11 years ago. After learning the ropes in private equity, then in the renewables business, he was named CEO of Brookfield Renewable Partners in fall 2020, not long after Mark Carney, one of the world’s foremost voices on the urgent need for a climate transition, also joined Brookfield, where he’s vice-chair and head of transition investing.

In fact, Teskey was part of the pitch made by Bruce Flatt—the driving force behind the Brookfield empire—to lure the former central banker to Brookfield. “We have this fantastic person, really first-class manager, developer of people,” Carney recalls Flatt telling him. “And we would need all those things.”

For the past three years, he and Teskey have worked together to build a new strategy for Brookfield’s renewables investments and to launch the first Transition Fund. Now, they’re back in the market raising a second, larger fund that’s expected to reach at least $20 billion.

Brookfield’s approach has been to largely focus on meeting corporate demand for clean energy, such as agreements to supply companies with power, rather than with centralized utilities or governments. “Really, what is driving decarbonization on a global basis today is corporate demand,” Teskey says. “It’s much more a corporate pull now than a government push.”

The Globe and Mail

In some respects, Brookfield has chosen a safe path toward decarbonization. It’s not investing in the bleeding edge of clean-tech innovation, because Brookfield doesn’t like taking what Teskey calls “binary risk”—investments where the returns can plunge if a technology doesn’t progress or a key permit isn’t approved. Instead, the vast majority of its investments are in the most mature technologies that carry lower risks—think solar and onshore wind power. For investors, many of those projects can be substantially “de-risked” at the outset, Teskey says.

When investing to build a renewable energy project, Brookfield likes to lock in as many variables as it can up front—financing, contracts for revenue and capital expenditures, engineering and construction. “At that point, as long as you execute, your investment return is largely secure,” he says. “It works throughout market cycles.”

From another perspective, Brookfield has been wildly ambitious. When it raised the first Transition Fund, investors asked how it planned to spend so much money. But in barely two years, Carney says Brookfield looked at a backlog of over $80 billion in possible transactions and whittled that list down until it had put every dollar to work. “It’s amazing, the velocity and the quantum at which they’ve been able to do that,” says Jake Lawrence, group head of global banking and markets at Scotiabank, which counts Brookfield as a client.

Its investments span a wide range of assets. Last year, Brookfield teamed up with Cameco Corp. to bet on surging demand for nuclear power by buying Westinghouse Electric for $4.5 billion, plus $3 billion in debt. It spent $2 billion on two U.S.-based solar and wind operators. It pumped hundreds of millions into investment agreements with companies in Calgary and California deploying carbon capture and sequestration technology. And earlier this year, it invested $1 billion in India-based Avaada Group, an energy developer with expertise in green hydrogen.

Brookfield is already thinking bigger. “A $15-billion or $20-billion pool of capital, the ability to cut $1-billion or $5-billion cheques sounds big,” Teskey says. But when investing alongside the largest power, industrial and tech companies, “it’s nothing in the context of the size of those businesses.”

The challenge of pulling off a global climate transition is even more enormous, likely requiring trillions in investments over the coming decade. Yet, in the near term, Brookfield’s investments in renewable energy and reducing the carbon footprints of large emitters have a real chance to move the needle. It has a long-term pipeline to develop 134 gigawatts of energy, and by 2024, it expects to be deploying about seven gigawatts each year—roughly enough to supply as many as seven million homes for a year.

After plenty of heated debate between editors and reporters from across The Globe and Mail, these are the top five executives across the Canadian business landscape that deserve to be celebrated for their outstanding achievements.

The Globe and Mail

Brookfield isn’t new to investing in renewables. The company started buying hydroelectric plants in the 1980s and packaged up some of its power assets to be listed publicly in 1999, when Teskey was a sports-obsessed 12-year-old in Vancouver. (Brookfield Renewable Partners itself has existed since 2011.)

Teskey moved east to attend Western University, where he was a lightweight rower. Once there, “my order of priorities was sports one, school two,” he says. “I love sports. I love the competition of it. It teaches you hard work and working through problems.”

His career started on the trading floor at CIBC, doing corporate debt origination. “He was a natural leader, he was a remarkably quick study, and he was really driven to be successful,” says Susan Rimmer, his first desk head. After three years at CIBC, he joined Brookfield’s private equity group in 2012. Four years later, he moved to renewable power in London. “What was interesting is I had no renewable power or utilities background,” he says.

Today, his expertise in renewable power, particularly as an investment manager, is “right up there with the best,” says Carney, himself a force of nature in sustainability circles. Under his and Teskey’s leadership, the business has expanded rapidly.

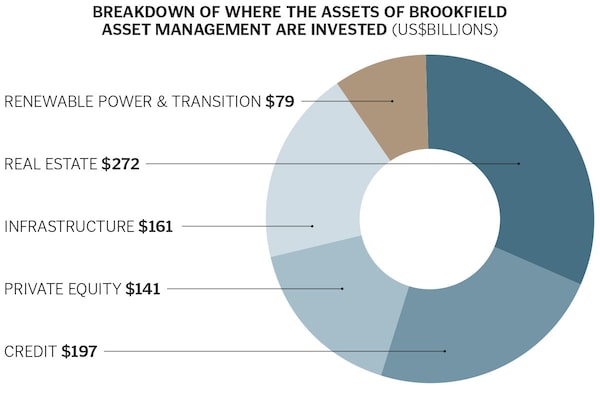

The first phase was built in the throes of the pandemic. Brookfield is well known for having been at the vanguard of returning to offices. After all, it manages a $272-billion real estate portfolio that includes office buildings in major financial centres.

Even so, Carney remembers building the strategy in part through video calls with 40 or 50 people on screen, hashing out what sorts of investments should be chased or passed up. At the same time, Brookfield Renewable Partners more than doubled its staff—it now has 120 investment professionals across 20 markets.

Mr. Teskey's career started on the trading floor at CIBC, three years before he joined Brookfield’s private equity group in 2012.

The public image of that staff is a battalion of people in Brookfield’s uniform of dark suit, white shirt and plain tie. But Carney and other Brookfield executives have been accustomed to seeing Teskey taking late-night calls from his dimly lit home office in London, draped in an oversized red Stanford hoodie and speaking softly as his first child—born less than a year ago—slept nearby.

Brookfield operates across several time zones, and Teskey works a lot—even by Brookfield’s exacting standards. “He’s virtually always accessible,” says Carney.

Clients agree. Rimmer, who now does business with Brookfield as CIBC’s head of global corporate and investment banking, remembers Teskey having a “remarkably strong work ethic—just relentless passion.”

Teskey was involved in Brookfield’s $5-billion deal to buy a majority stake in Oaktree Capital Group in 2019, forging a partnership that brought together Flatt and Oaktree co-founder Howard Marks to run a $500-billion money-management colossus. That tie-up is the transaction he’s most proud of. The partnership “has been so mutually beneficial,” he says—it changed Brookfield’s competitive position, boosting its clout in the sector.

“There are lots of smart people,” says Scotiabank’s Lawrence. “There are lots of people who are mature. But Connor’s work ethic multiplies those.”

As Carney puts it, “He is a guy who’s rolling up his sleeves and can drill down into a transaction.”

Over a video call from London—where darkness has fallen, and Teskey’s plain white shirtsleeves are indeed rolled up—he says Brookfield is “the place I never want to leave.”

His ascent has been rapid. Late last year, he added another title: president of Brookfield Asset Management, which oversees $850 billion in assets. Combine that with his job as CEO of the renewables arm and he has established himself as a top lieutenant to Flatt—leading to speculation that he’s a possible heir to the top job.

For now, he has his hands full raising billions in an environment shaped by rising rates, slowing growth, sluggish deal-making and escalating geopolitical strife. So far, Brookfield has largely shrugged off those headwinds, raising new funds briskly and relying on its locked-in contracts, some of which are tied to inflation and have helped prop up returns. But he acknowledges that Brookfield will “need to be razor-sharp about that discipline when times are a little bit more uncertain.”

Of late, the Brookfield Renewable Partners share price has struggled, signalling that some investors are still hesitant. But at a presentation in September, Teskey tried to put to rest concerns about whether the renewables market can continue to expand as profitably as it has in the past. “The great news is the renewables market is so rich with opportunities, you can be disciplined without restricting your opportunity set,” he says.

Brookfield’s approach is likely to stay much the same, he says, and its appetite for deals is still growing. “There is so much room to go bigger.”