Canadian Tire's new Vida by Paderno toaster.Jon Laytner/The Globe and Mail

The raccoons refused to co-operate.

This, in Toronto, is not unheard of. For anyone who thinks humans run the city, these fuzzy miscreants have a retort—in the form of a colonized balcony, a bellicose swagger through a backyard party, nocturnal shrieks from a nearby treetop, or the stinking wreckage of a looted garbage bin. But for raccoons to refuse to eat trash? That was a new one.

And it was particularly frustrating for Brennan Chiu, a product development designer at Canadian Tire Corp CTC-A-T. His mission was to test a design he’d been working on for months, one of thousands of new and revamped products the company is launching as part of a strategy to increase sales of its higher-margin private brands. The contraption was designed to raccoon-proof garbage and compost bins, with a handle that screws into the bin’s lid and pulls synthetic rubber straps taut to keep it closed.

Chiu and his team believed this device would be easier to use and more effective than competing products already on the market. They’d done the customer research, built multiple prototypes and figured out the pricing—$29.99. Now, they needed to test it in the field.

Chiu had even sweetened the deal, placing open tins of sardines inside a bin, smearing the rim with peanut butter and poking holes in the plastic sides to let the aroma through. But when he left the bait in his (very tolerant) parents’ backyard, with a motion-activated camera trained on it…crickets. Next, he tried a friend’s place, adjacent to a ravine—a ravine!—and still, nothing. He even talked to some rescue centres to see if they’d be willing to test it out with resident raccoons. No dice. The next step would be to distribute samples to co-workers, friends and family members for feedback. And if one of those testers had an existing raccoon problem—since the pesky critters tend to return to sites where they’ve had luck before—all the better.

After all, Canadian Tire’s mantra is “Tested for life in Canada”—and an unmolested trash bin certainly doesn’t reflect that reality. Would the mint additive in the straps deter varmints from chewing through them? Would the durometer strength be sufficient to prevent little paws from flipping the handle and loosening the mechanism? There was only one way to know for sure. But with the clock ticking toward launch day, “unfortunately, we didn’t get much interest,” Chiu says incredulously.

Organic waste bin equipped with a late stage prototype of Canadian Tire's new anti-raccoon device.Jon Laytner/The Globe and Mail

The possibly-raccoon-proof bin accessory is just one of many items the company has been testing at its product development labs in Toronto and Calgary before shipping them to Canadian Tire stores and those of its other banners, including SportChek and Mark’s. The push is part of a sweeping four-year strategy launched in 2022, to improve operations and increase sales. The plan, dubbed “Better Connected,” was designed to bring the century-old retailer into the future, with investments in e-commerce, digital technology in stores, added warehouse capacity and automation, and expansion of the Triangle loyalty program. And it’s all happening as Canadian Tire, like many retailers, fights for scarce consumer dollars against major players who are competing fiercely on price and convenience.

Private-label products are a major part of the plan, too. When Better Connected was first announced, after two years of pandemic-fuelled buying that boosted sales of home-improvement and recreation products, the goal was to launch 12,000 stock-keeping units, or SKUs, by the end of 2025. (In total, the chain sells nearly 200,000 products already.) Some of these would be brand-new items, like the raccoon guard, while others would be refreshes of existing items to keep the assortment relevant. Canadian Tire set a target for its owned brands—a business with $5.7 billion in sales in 2022, including Noma lighting, Mastercraft tools, Canvas decor, Paderno kitchenware and more—to account for 43% of sales by the end of next year, up from 38% in 2022.

Uncooperative trash bandits haven’t been the only complication. Canadian Tire has been forced to revise its ambitious plan, slowing down investments and cutting more than 200 corporate jobs, as the economy sputters and consumers pull back on non-essential spending in the face of rampant inflation. Those revisions include slowing the pace of product launches. With existing merchandise not selling at the expected rate, the company has to manage its current inventory first before stocking the shelves with new stuff.

Still, in the long term, these hurdles don’t change Canadian Tire’s goal for its owned brands to gradually take over a bigger share of every shopping cart. “A bit of that you can do through driving more sales of what you have,” says Bobby Singh-Randhawa, Canadian Tire’s senior vice-president of consumer brands. “And some of it is going to be, we’re going to continually add product where it makes sense.”

Being able to do that has required a major change in how one of Canada’s biggest retailers approaches its products—not to mention building far more robust design and development teams, a process that began more than seven years ago.

“Canadian Tire didn’t have—and I would say most retailers don’t have—a true design and development function,” says Anthony Wolf, vice-president of product development and innovation, standing in the consumer brands department at the company’s Toronto headquarters. “This whole capability has been years in the making.”

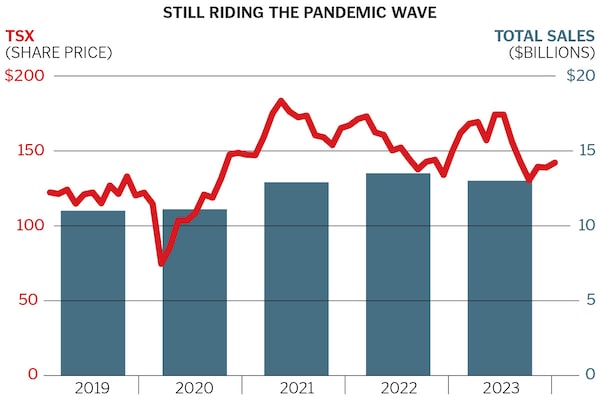

The Globe and Mail

With so many products in the hopper, Canadian Tire’s Toronto offices are cluttered with items at every phase of development. There’s a slew of products they’re responsible for: The company’s owned brands sell everything from air fryers to antifreeze, Christmas lights, cornhole games, dinnerware, dehumidifiers, jumper cables and jujubes, to mention just a sliver of the inventory. On one afternoon, in a dedicated 3-D printing room, a humming machine was churning out a black plastic prototype of a toolbox organizer, while across the hall, an array of can openers was spread out on a table for the kitchen team to compare rival products to their own designs. (A bottle-opener attachment, which might seem like a “nonsense add-on,” Wolf says, proved surprisingly important in customer research.) The department is a warren of cubicle dividers separating the various category teams: In one area, designers milled around a whiteboard covered in Post-it notes under the headline “Project Nitty Gritty,” brainstorming gaps in the market for sandpaper. Down the hall, a bucket sat on a table, a piece of tarp draped loosely over the opening and clamped to the rim. The tarp held a shallow pool of water, a test of the waterproof repair tape covering a rip in the material. The product passed—the water didn’t leak into the bucket, and the tape will be sold this summer under the Certified brand.

The department also has a separate room—specially ventilated and soundproofed to spare colleagues the cooking smells and noise—where it tests products like kitchen appliances, tools and electrical components. Inside, a counter was littered with toast—18 pieces, to be exact, lined up in gradations of colour from a barely sun-kissed ecru, through shades of toasty gold and charred russet—the result of trials on a toaster in the Paderno line, a brand Canadian Tire bought the rights to in 2017. The toaster launched a couple of years ago, but recent changes to its heating element meant it was back to the test lab in Toronto to make breakfast for no one. “We just want to validate that we’re getting the results we need,” says Wolf.

The retest was relatively straightforward, especially compared to when the toaster was first being manufactured. Testing the product back then meant hauling some unusual luggage to the factories in China. “We were carrying suitcases full of North American bread,” Wolf recalled, “to make sure we got the right results. Bread in those regions isn’t the same—not the same moisture, the bread size is different.” So naturally, the baked goods racked up some serious air miles. Canadian Tire employees took more than 30 loaves of white Wonder Bread over the course of five trips to China, and retested with dozens more loaves in Canada to check that their results were consistent.

This toaster is more than just a small appliance, though: It’s a window into how Canadian Tire’s product strategy has shifted over the past decade.

First, it’s an example of a brand the company didn’t even own just a handful of years ago: Canadian Tire’s acquisition of Paderno was one of several investments the retailer has made to build out its portfolio. It acquired the Woods camping-gear brand in 2014; both the Helly Hansen outdoor apparel line and Sher-Wood Athletics Group’s hockey trademarks in 2018; the Canadian rights to Muskol insect repellents in 2019; and the exclusive rights to Canadian production and distribution for bike brands such as Raleigh and Diamondback, also in 2019.

Second, at $125 a pop, this toaster is an illustration of Canadian Tire’s efforts to improve the quality of its own products and to push into a wider range of price points.

The retailer’s owned brands cover more than 200 categories across its store banners, and they vary in price and quality. Executives refer to the three tiers of their products as “good,” “better” and “best”—marketing speak for discount, mid-priced and somewhat spendy. “We were traditionally playing at the ‘good’ level architecture,” says Canadian Tire CEO Greg Hicks.

In the past, that meant “quality wasn’t necessarily our strength,” chief brand and customer officer Susan O’Brien said during an appearance at a Scotiabank conference this past September, recalling the state of the product lines when she joined Canadian Tire in 2008. Since then, the chain’s buyers have been challenged to bring in better products. And particularly in the past few years, the private-label brands have been looking at ways to improve.

“Do you really want to sell a $10 toaster with a really high product-defect rate?” says Hicks. “Or do you want to adjust that low-level architecture—work on the features and the benefits and the technical specifications that drive more quality into the ‘good’ level?” (Master Chef, the company’s “good” brand, prices its toasters at roughly $35 and up.)

Motomaster, Canadian Tire’s oldest brand, with more than 1,400 products, has also undergone a full relaunch. Some categories were added, others discontinued, and quality standards were improved.

The other side of that strategy is what’s referred to internally as a “push to premium,” launching products on the higher end of its assortment where big brands—which Canadian Tire also sells—have traditionally dominated.

In the Toronto office, Wolf points to samples of products launching this year under the Vida by Paderno line. Electric kettles and toasters will come in Pantone shades of Vanilla Bean, Matcha and Blue Fin, with matte finishes. The line is designed for customers looking for a more stylish, “Instagram-worthy” aesthetic, he says.

At a time when consumers have been feeling the sting of inflation and higher interest rates, which have squeezed household budgets, the idea of selling more premium products might seem out of touch. But Hicks believes having items at a range of prices serves the retailer well. “We certainly still lean heavily into our high-low model,” he says. “So there is opportunity for Canadians to save money.”

Improving the quality of Canadian Tire’s own products has also had an effect on the kind of big brands that consider selling their products there. Hicks says he couldn’t imagine that five years ago, a brand like retro-chic kitchen appliance maker Smeg would have considered Canadian Tire as a sales channel for items such as a $350 drip coffee maker or a $250 kettle. “But that evolution of the product quality—and that range, and our positioning and the strength of our owned brands, and the market-share appreciation that has come with that type of assortment strategy—has led national brands to really think differently about Canadian Tire.”

A trio of product developers work on the electrical interface for a new recumbent bicycle developed for individuals with cognitive or physical disabilities.jim krantz/The Globe and Mail

If they think about store brands at all, many shoppers probably associate them with the off-brand products on grocery shelves—the box of generic Os next to the Cheerios or the not-quite-Coca-Cola.

Such generic products are good for retailers in a couple of ways: They can attract customers to your store looking for a deal, for one. And even at a lower price, these store-brand items often yield a bigger profit margin. That’s because there’s no big-brand supplier to take a cut of each sale—the retailer controls the manufacturing. And a private brand doesn’t have to spend as much on advertising: The shelf is the billboard. In a recent survey by McKinsey & Co., procurement leaders reported plans to increase private-label purchase volume over the next one to three years by 21%. Private-label products can yield as much as double the gross profit margin of national brands, according to McKinsey.

“The fundamental rationale behind the strategy was margin accretion. We were trying to build a bigger margin profile than the national brands,” Hicks says of Canadian Tire’s primary focus in its owned-brand business in the past. It’s still part of the picture, but in recent years, he adds, the approach has become “much more sophisticated.”

Part of that is due to the work the team has done on quality, but also, as Canadian Tire has made acquisitions, the line between private-label and name-brand products has blurred. And the company has been expanding on the brands it has bought. Helly Hansen is launching products in new categories such as footwear, as it aims to triple its business in Canada and expand its market share internationally. Paderno, which was a relatively narrow cookware line when the company acquired it, has branched out into myriad gadgets and small appliances. Across the Canadian Tire chain, the line is doing roughly 20 times the sales it had pre-acquisition, Singh-Randhawa says. Sherwood Hockey has also been working to modernize its products. Last August, the brand got a major boost, signing an exclusive deal with star player Connor Bedard; the Chicago Blackhawks centre and No. 1 pick in last year’s NHL draft now plays exclusively with Sherwood’s sticks and gloves. And in the Toronto offices, a mannequin is decked out in the newest line of Sherwood protective gear designed specifically for women’s bodies, an effort led by a female product development manager, Nicole Wiart, and brand manager Charmaine To. Part of the testing has involved gathering feedback from high-level female players on products such as shoulder pads and hockey pants.

None of this means that big-name brands are going anywhere—they still make up the majority of Canadian Tire’s sales. But those categories are competitive. Shoppers can get that Dyson vacuum, Coleman tent, Cuisinart kettle or DeWalt drill elsewhere. They don’t have to go to SportChek for a North Face jacket or to Mark’s for a Sorel boot. But if customers like a store brand that they can only find in one place, it provides some competitive insulation.

“It has to do with customer loyalty and driving traffic to the store,” says Kyle Murray, a retail consultant and marketing professor at the University of Alberta. Canadian Tire may be a large Canadian retailer, but it’s still dwarfed by the likes of Amazon and Walmart, rivals that compete fiercely on price and marketing. “Retailers would prefer not to be in a race to the bottom on margin. If Amazon can’t sell your tent, you can’t get price-shopped to death in the same way,” he says.

SportChek was one banner in need of more products exclusive to its stores. “They were very national brand–dominated,” Wolf says. The company launched its first activewear line, FWD (or Forward With Design), in 2019, starting with bags and accessories, and expanded into apparel in 2022. The products, which now span 800 SKUs, are designed to appeal to athleisure shoppers, often at a 15% to 30% discount compared to brands like Under Armour (which the stores also sell) or Lululemon and Athleta (which they don’t).

Moisture-wicking “commuter pants” with zippered pockets have performed well for FWD. A high-support bra required two years of development, multiple sample trials with prospective customers and “countless design iterations” before launch, says Sharon Kumar, Canadian Tire’s associate vice-president of lifestyle, beauty and wellness. Women’s active swimwear will launch this year, starting in Quebec-based Sports Experts stores. FWD is now one of the company’s biggest owned brands and is among the top 10 apparel lines by revenue at SportChek.

Eventually, Wolf would like to see FWD become a kind of name brand itself, selling in other countries through stores the company doesn’t own. Very few of Canadian Tire’s brands do this. Helly Hansen, which was already a global brand when the company bought it, is one. Others, such as Mastercraft, Paderno and Motomaster, have limited sales in the U.S., mostly as a placeholder to maintain their trademarks in that market. Theoretically, if FWD were to take that leap, the company could make use of Helly Hansen’s distribution network, which has global connections to similar customers.

“I’m very bullish, because I really do believe there’s more to unlock,” Wolf says, though he admits the move would be a big change. “You’ve got a whole infrastructure for dealers and merchants, and now…you’re the vendor on the outside.”

Taking a prototype of the car-wash caddy for a test run in the parking lot at Toronto headquarters.Jon Laytner/The Globe and Mail

The design started with coffee cups and popsicle sticks.

This prototype—for a cart designed to hold buckets and supplies for washing a car—has evolved into a full-size wooden version, with a plastic shelf for spray bottles up top and a tilted rack for buckets below. The next step will be to buy some samples made of metal and to see which vendors in China can offer the best option. “The hard part of design is actually making it manufacturable, to ship at a good price. We’re at that stage right now,” says David Green, the product development manager in the automotive category. “How to break it down, make it strong enough, but make it easy for the consumer to assemble it—that’s the real nuts and bolts.”

Having control over manufacturing is a benefit for many private-label brands, but it can also expose retailers to commodity-price fluctuations—a challenge in recent years when supply chains were volatile. That’s a factor in the prices stores can offer to inflation-weary shoppers. From 2019 to 2021, during the height of complications related to COVID-19, the price of cold-rolled steel—used in everything from metal toolboxes to trampoline frames, car jacks to basketball nets—rose 47%. As a result, quotes from vendors who make these products rose by 12%. Costs have since fallen by 8% off the 2021 peak, but they’re still not back to pre-pandemic levels. “It requires us to act with speed in our vendor negotiations, and to bring the pricing down so we can pass that on to the customer, to create that value,” Hicks says. “That’s so important right now.”

The team is also looking at how to push prices down before products hit the market. The rolling car-wash cart started with a target retail price of $165, but the designers made adjustments, figuring it would sell much better at $100.

Before they ever get to that stage, however, product developers have to be sure people actually want what they’re making. For the cart, that effort began months earlier, with employees watching people who’d agreed to be surveilled while washing their cars. The developers asked their test subjects what they were thinking and feeling as they moved through the chore, noting pain points and product opportunities. The team then surveyed hundreds of members of its customer panel—a pool spanning roughly 200,000 people who provide feedback on ideas—to test those findings across a wider group. The result was an “opportunity score” that told the team where to focus their efforts.

Tacked up on a wall in the auto development area are illustrations of some of the resulting ideas for the Simoniz brand, including new sponges, a tool-cleaning product and a mobile cleaning kit. The research also led to new chemical products, launching in the spring, that are designed to remove winter schmutz from cars. The company hired a chemical engineer whose work included tackling the vicissitudes of corrosive road salt. Another round of products will launch in the fall to protect cars ahead of winter. “A lot of our competitors, the national brands, they’re all based in California,” Green says. “They don’t know our pain.”

All this work must strike a delicate balance: not moving too fast as the chain rides out a rocky economy, while building up its inventory of Canadian Tire products over the long run. If those products can win over customers, it just may be one more reason they consider shopping there rather than at a competitor. And there are plenty of competitors. With a product assortment spanning sports equipment, tools, party supplies, appliances, cleaning products and more, a wide variety of retailers across Canada and online compete with Canadian Tire in at least one aisle.

For a new product like the raccoon guard to have a chance at the lucrative spot in one of those aisles, the ultimate test comes once a year: the Canadian Tire dealers’ convention. The annual gathering of hundreds of store owners includes a massive trade show known as the “product parade,” where the dealers get a look at new and upcoming items and decide which ones to stock.

A good showing at the parade can change an item’s fortunes. At the most recent convention in Edmonton last fall, the raccoon guard drew “tremendous” interest, Wolf says—so much that the category merchant responsible for dealer sales doubled her forecast.

There was just one final test it had to pass, one more group of tough customers to plan for. “They’re quite crafty,” Chiu says. “And they have opposable thumbs.”