Canadian music promoter and the CEO of the Global Touring division of Live Nation Entertainment Arthur Fogel at the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles, California.Maggie Shannon/The Globe and Mail

As a high school kid in Ottawa, Arthur Fogel dreamed of a career in the music business. Little did he know that U2 frontman Bono would one day call him “clearly the most important person in live music in the world.” All those globe-hopping mega stars—Taylor Swift, Madonna, Lady Gaga, Beyoncé and the rest? They can thank Fogel, in very large part, for redefining what a concert tour could be. He did it first, 35 years ago, with The Rolling Stones. Working at Toronto’s CPI, he took a group that even then many considered over-the-hill, bought up all the tour dates and turned them into major events. The 1989 Steel Wheels tour spanned 20 countries, grossed US$170 million and became the biggest tour of all time. Later, at Live Nation, Fogel did it again (Madonna’s Sticky and Sweet tour, 2008-09, US$408 million gross) and again (U2′s 360 World Tour, 2009-11, US$750 million gross), and along the way he took many other artists to new heights. What does Live Nation’s president of global touring now think of all that he has wrought? We spoke to him via Zoom at his office in Los Angeles, overlooking the Hollywood Hills.

People say you’re the guy who made global touring a proper business. What was it about touring that you changed?

I certainly can’t claim all the credit. When I was working for Michael Cohl at CPI, (1) there was a lot of discussion and strategizing about how to grow us as a company. And as a Canadian, there’s a limited marketplace. So it was a question of, how do we take it beyond, into a global reality? The global touring model came from that strategizing.

At the time, the business was more localized. Promoters had regional fiefdoms.

Absolutely. And it was very controversial and difficult trying to move out of that model into a different model. But the globalization of the music business has evolved unbelievably. When we started, there were 15 to 20 countries in play on an itinerary for an artist, and now there’s 70-plus. The development that you’ve seen in Latin America, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, has really opened up what a global tour is in 2024.

Last year, Live Nation did about 100 global tours. How many of those were you involved in personally?

Basically, I wear two hats. One is that I oversee the touring for a handful of long-term clients. (2) The other hat is a sort of 10,000-foot watch over all of the company’s touring activity. When Live Nation was born in 2005, there were basically two paths. One was global touring acquisition and execution, and the other was building out a local infrastructure around the world where we now have, I don’t know, 70 offices. So we captured both sides of the business—the touring side of the business, and also the still vibrant local business that remains a part of the live reality. (3)

For the handful of tours you oversee, how involved are you? What do you get into?

Minutiae. I have a staff of people who’ve developed a great expertise in executing these global tours. But I wanted to get to a point in my career where I could sit with an artist and talk about a touring strategy and be able to talk about Sydney the same way I could Montreal or Chicago or Amsterdam. There are incredible big-picture advantages to a global deal for artists. Everything from the financial stability and the ability for us to make artists more money, but also from a marketing, profile-raising perspective with the great assets that we have. They look to us to provide a consistency and an execution on a global basis, as opposed to having to go to different people a hundred times over the course of a tour.

I want to drill down into some of the minutiae. Merchandise—how much of a revenue generator is that at concerts?

It can vary dramatically depending on the artist and the fan base, but it is a significant part of revenue potential for an artist on tour, no question.

Did you recently give local venues a piece of the merchandise revenue stream?

No. What we recently did was, in our clubs and small venues, we eliminated the merchandise fee. To help deliver more bottom-line revenue to young developing touring artists, who in many cases are struggling financially on tour.

For a big tour like, say, Madonna’s recent Celebration tour, how many people are out there working for you?

In terms of the actual tour execution via marketing, ticketing, production, probably a dozen people. Within the Madonna touring organization in terms of crew and staff, you’re talking about 150 to 200 people on tour.

How do you determine whether a show will work financially?

The foundation of any show or tour deal is, what do we want to charge? When I say “we,” I mean the artist. And then it’s a question of, how many tickets are you going to sell? You’re laying down the bet every day, multiple times. Now, one would say there’s not much of a bet for Taylor Swift or Beyoncé or, pick the superstar, because she’s going to sell every ticket. But there’s a whole level of activity where there is risk. And if you sell 8,000 tickets instead of 10,500 tickets, times the ticket price, we can all do that math. And when you apply that to a tour deal, you multiply it by 80 shows or 100 shows. So if you’re wrong 80 or 100 times, it can be very material.

I’ve seen figures that suggest touring now represents about 70% of an artist’s revenue. Is that roughly accurate?

To be honest, I don’t know. I’m not that in tune with the economic reality of streaming. But I don’t think there’s any question that the live part of an artist’s career is by far the biggest piece of revenue and revenue potential.

Roughly speaking, how much of the revenue from a global tour goes to the artist?

That varies depending on ticket pricing, and the size and scale of a show. But I would say, in a general sense, it’s 50% to 60%.

What is it about you, and the way you deal with artists, that makes them want to work with you?

In the simplest form, I’m right a lot more than I’m wrong. [Laughs] Because I think I do have a sensibility and an understanding of the artist’s side, but if you don’t deliver, that doesn’t go down so well. And I’ve always played long. A lot of my personal artist relationships are based on that. As opposed to the quick-buck notion of old-school promoters. And ultimately, working to the artist’s agenda has always been top of my list, as opposed to any other agenda. I think that’s appreciated.

Bill Zysblat, David Bowie’s manager, said that when it comes to artistic issues for a show, “Arthur just caves.” Is that accurate?

It’s pretty accurate. Listen, I’ve always believed in “the show.” Performing live is its own art form. The reason people keep coming back, obviously, is the music, but it’s also the presentation, the show. So I would never sit there and go, “Well, why would you do that? You can get away with less.” An audience can feel what’s gone into creating a spectacle and the joy that comes from that. I’ve always believed that’s paramount to the live success.

Not every leader works with artists, but many deal with talented, temperamental people. What’s your key to getting the most out of them?

Honesty, I would say. What you find in that world of big-time artists and celebrities is there’s always a lot of people around who just nod their heads or agree, not necessarily because it’s right, but because they’re concerned about their positioning. But I’ve always been the opposite. You never want to be caught out for having agreed for the sake of agreeing to pacify. You want to have stated your view so that it was on the table. And if something went wrong or somebody asked the question, “Why was it like that?” Well, I was honest and forthright about why it didn’t make sense.

You’ve said you love the action of the road and you love troubles. Why?

It keeps you sharp to have to deal with the unexpected. It can be anything from weather to security issues, to health and safety issues, to personnel issues. There’s all kinds of scenarios.

What’s the worst trouble you’ve had?

Probably the worst situation I found myself in was in Paris with U2 during the terrorist attacks. (4) It was a very difficult situation that required an enormous amount of adjustment for a lot of people. Things like that happen that nobody can predict. So while it all seems glitz and glamour, there is an underbelly of things that can go wrong, that can be very serious.

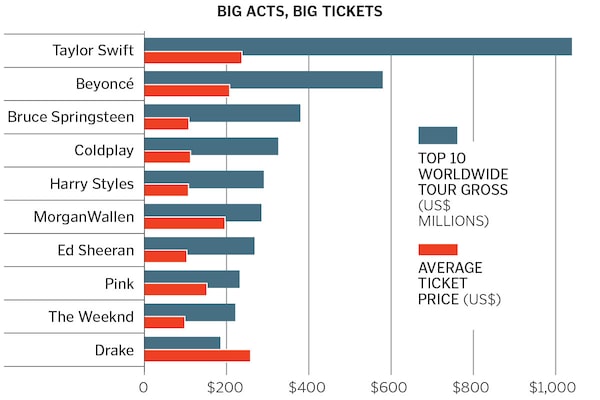

Let’s talk about ticket prices. Why have they gotten so crazy—$1,500 to see a show at Scotiabank Arena?

I think generally there’s an acceptable pricing model for shows. There’s no question some tickets are very high, but also some tickets are very cheap and affordable, and as with anything in life, you can make that choice. I have always believed we are underpriced as an industry. You want anybody to be able to afford a ticket, but artists deserve to make a living and a profit. These productions are incredibly expensive to mount and operate on a weekly basis. There’s this perception that a high ticket price means outrageous profit margins, and the truth is, it doesn’t. (5)

In 1970, someone I know went to a show at the Ottawa Civic Centre that featured Yes, Black Sabbath and Alice Cooper. The ticket cost $15. How does a young music fan today get an experience like that?

I think there’s a lot of shows that fall into that pricing reality. Maybe today it’s $25 or $30. The aim of the pricing model is to satisfy the range of buyers. The top-price ticket always gets the headline, right? But that $15 ticket—I can’t imagine what it cost to run that show back then, but probably not very much.

What’s your view on resellers?

Outlaw them. That’s my view. But in the true definition of capitalism, it probably never happens. Part of the reason ticket pricing has gotten higher is because artists, rightfully so, have demanded a bigger piece of that vig, if you will. Because you have these sophisticated broker networks and scalpers buying up tickets, and reselling them for a much higher price, but the artists have no sharing position in that vig, which is fundamentally unfair. And so you have this vicious cycle.

I know you don’t represent Ticketmaster, but do you have any insight into what happened with the Taylor Swift ticket debacle? (6)

My sense, from what I’ve heard or witnessed myself, was you had the perfect storm of supply versus demand. The demand far exceeded the supply, and in the mix of all that you had very sophisticated broker networks, bot networks, that were attacking a ticketing system to grab inventory. But the controversy of supply versus demand doesn’t really address the fundamental problem, which is, not everybody’s going to get a ticket to some shows because there just aren’t enough.

The past few years, Live Nation has been the target of some legal action. (7) What’s your response to people who accuse the company of being a monopoly?

Oh, I think the facts clearly support that’s not true in the slightest. There’s no question we’re a big company, and we’re successful. But we’re really good at what we do. Maybe others need to get better at what they do, to come at us better. It’s not something I spend a lot of time thinking about.

What would you say to Jerry Mickelson, CEO of Jam Productions, who said Live Nation drove them and other independent producers out of the sector? (8)

I think we created a business model that is very attractive to artists and their managers and representatives. We’re really good at maximizing ticket sales and artists’ revenue, and catering to their needs and supporting them when they need it. Why was there Wayne Gretzky and a bunch of other people you don’t remember from that era? It’s not about intentionally going out to squash Jerry Mickelson or anybody else. It’s simply working out our agenda as well as our business plan.

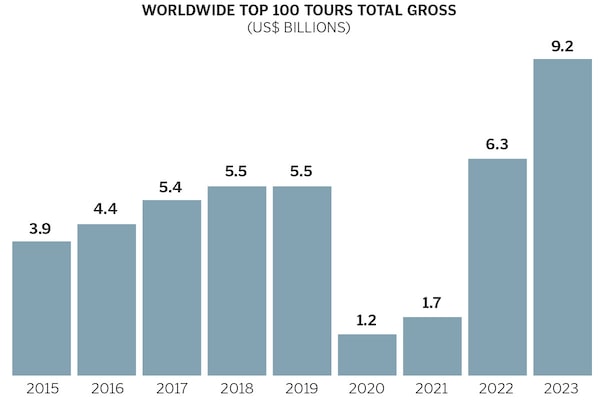

A lot of the shows you’ve done recently—U2, Madonna, Sting, Peter Gabriel, Neil Young—feature artists in their 60s or 70s. Is the global tour business aging out?

No, it’s the opposite, actually. There’s a younger generation of headline artists that fill arenas and stadiums, different genres—the Latin world, comedy, country, K-pop—that have developed and exploded. The audience has expanded. And if you look at any of these legendary artists, whether it’s the Stones or U2, they have also regenerated their audience. If you go to an AC/DC show, I guarantee you’re going to see a lot of kids there. So the business has never been healthier.

Is there anything about live shows as they’re constructed now that you would change, if you could get everybody to do one thing?

As an industry, I think we need to do a better job with sustainability. The mass of a show—more trucks, more planes, more this, more that— is part of what creates the issue. That’s why Sphere in Las Vegas, and the venue concept, is so exciting. Because it’s about the venue and how the venue is constructed technologically, as opposed to bringing tons of shit to create the experience. The U2 show is brilliant. (9) But on that level, it’s exciting because it really changes the dynamic of show presentation in a responsible way.

You like the idea of a big show that stays in one place.

It has tremendous advantages logistically, financially, experientially.

Except a kid in Ottawa can’t see that show.

No, you have to go to Vegas.

The Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail

1. Concert Productions International

2. In the past few years, Fogel has been personally involved in tours for U2, Lady Gaga, Beyoncé, Madonna, Sting, Peter Gabriel and Neil Young.

3. Live Nation owns or manages 338 venues. In 2022, it promoted shows or tours for 7,800-plus artists. Its concerts segment (the others are ticketing and sponsorship & advertising) generated US$13.5 billion, roughly 80% of total revenue.

4. In 2015, U2 was scheduled to perform two arena concerts in Paris that were cancelled in the wake of the Nov. 13 terrorist attacks that killed 130 people, including 89 at the Bataclan music hall.

5. In 2022, the average ticket price for a Live Nation concert was US$108.20

6. Live Nation and Ticketmaster merged in 2010. In November, 2022, when tickets for Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour went on presale, the online system crashed, many fans were booted from the virtual queue, and Swift pronounced the whole mess “excruciating.” Even so, some 2.4 million tickets were sold in one day, an all-time record.

7. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice alleged Live Nation had violated an anti-competition decree it signed when it merged with Ticketmaster. Several class actions have accused it of anti-competitive ticket practices, and in November, the U.S. Senate subpoenaed Live Nation to provide records as part of a months-long probe.

8. During testimony in early 2023, Mickelson told the Senate Judiciary Committee: “Jam’s most profitable segment...was the shows the company produced in indoor arenas. Live Nation has effectively eliminated this part of our business.”

9. U2′s 40-show run at Sphere ends March 2.

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.