Ryan Garcia/The Globe and Mail

Any CEO or board under siege can’t say they weren’t warned. In January 2021, at the height of the meme-stock frenzy that sent shares of companies like GameStop soaring, the world’s largest activist investor cautioned that nothing was making sense—and there would be consequences. Businesses that had never made money were suddenly some of the most valuable, and borrowers were feasting on extremely cheap debt manufactured by major central-bank intervention.

No one would listen, of course. Maybe it was the boredom of being trapped at home during COVID-19 lockdowns, or maybe everyone was just a little bit drunk on the stimulus punch sloshing through markets. So, the best activist giant Elliott Investment Management could do was warn of trouble ahead. “We continue to press on for the day when we can say, ‘We told you so,’” the firm wrote in a letter to investors.

Activists like Elliott made their names by muscling in on struggling companies and then threatening to throw out board directors—and sometimes even CEOs. They’d notched some famous victories, like Bill Ackman’s overhaul of Canadian Pacific Railway in 2012. But by 2019, their tactics were getting a little tired, and a lot of copycats piled in, often looking to make a quick buck. The S&P 500 was also performing so well that investors could put their money in simple exchange-traded funds and earn just as much, if not more, than investing in a fund run by an activist investor, with way less hassle.

Then the pandemic hit and, after some early turbulence, the day traders and the meme stocks took over. Activists were completely neutered. Which is why Florida-based Elliott was shouting into the wind.

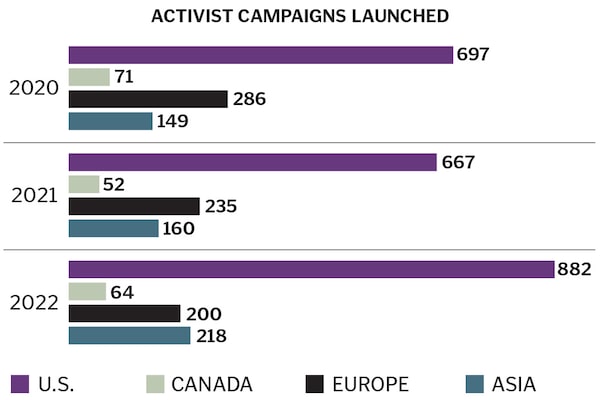

But now? Now the activists have every right to say, “We told you so.” Elliott and all its peers are back, and they’re fiercer than ever. Activists typically launch their board battles during the first half of the calendar year, because they like to propose new directors just a few months before a target company’s annual general meeting. (AGMs are where directors are elected each spring.) The first quarter of 2023 was the busiest three months ever for new activist campaigns, according to research from investment bank Barclays, and the first quarter topped the previous record set in the same period just last year.

These are merely the campaigns we know about. Roughly two-thirds of activist battles take place behind the scenes, says Ian Robertson, CEO of Toronto’s Kingsdale Advisors, which specializes in guiding boards and activists through these battles and advised Ackman on his shakeup of CP Rail. Lots of settlements are reached behind closed doors, with the public none the wiser. It’s usually only when the rabble-rousers feel like they’re getting the cold shoulder from a board that they go public. Kingsdale has been around for two decades, says Robertson, and the firm has never been this busy. “The last 14 months have been non-stop.”

Last year’s stock market correction is the primary driver. The S&P 500 fell 19%, and the Nasdaq Composite, the frothiest of them all, lost one-third of its value. But the bubble mentality has popped, particularly for technology companies, and activists finally have an opening to outperform the market. Sagging share prices have also given investors reason to hear the activists out again. Hardly anyone cares about governance issues or executive pay when stocks are rising—everyone’s making too much money to bother.

Canada has already seen some major campaigns, with TCI, a London-based money manager, forcing a CEO change at Canadian National Railway last year and installing Tracy Robinson, a former executive at rival CP and TransCanada Pipelines, as the new leader. Elliott did the same more recently at Suncor, bringing former Imperial Oil CEO Rich Kruger out of retirement in February to run the energy giant. But the battles are everywhere now—from commercial real estate to utilities to energy infrastructure.

Boards of directors might think they know how to handle activists because the activist playbook used to be pretty standard: Release a public letter to the board, propose a few new directors with relevant industry experience (maybe retired CEOs or executives) and call for some sort of strategy shift—sell off a division, say, or demand share buybacks. The kind of thing Kendall Roy might pull on his dad in Succession or, to use a real-world example, exactly what went down at Canadian agricultural gem Agrium in 2013.

But there are more plays to call now, and some are disguised by activists wrapping themselves in the environmental, social and governance (ESG) cloak. Elliott’s battle with Suncor, for instance, was fuelled in part by safety issues—the oil producer had 13 employees die on the job in nine years. Activists are also more likely to “swarm” these days. Once one of them has called out a vulnerable company, two or three or four will pile on and demand changes, and each of them might have different requests.

It’s all made for a mismatch. Boards and CEOs are still “unprepared and unrealistic about the threat activism poses,” says Robertson, echoing the advice bankers and lawyers routinely offer. “They believe the activist is going to go away.”

They’re wrong. And this is just the beginning of a new wave. “It is unlikely that today’s elevated level of activism will be curbed by legislation, regulation or market forces in the near term,” lawyers from Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz LLP warned clients in April.

What follows is a guide on who and what should be keeping directors and executives up at night.

The evergreen elephant

For years, Ackman, a Harvard grad who launched his own hedge fund, personified shareholder activism—particularly in Canada, because of his success at CP Rail. CP had been lagging for years, falling farther behind its Canadian rival CN, but CP’s board kept giving its management team more time. Ackman fronted the activist fight and won, installing former CN CEO Hunter Harrison as CP’s new leader. In 2012, this magazine named Ackman CEO of the Year for being the “boardroom barbarian who toppled four-star corporate generals at one of the country’s most historic companies.”

Lately, though, Ackman, who runs Pershing Square Holdings, has been preaching quieter, more co-operative fights, having endured some bruising campaigns since CP, including his disastrous short-selling campaign at nutritional-supplements company Herbalife and his unusual support for Valeant Pharmaceuticals, which saw its share price crater.

In Ackman’s absence, Elliott has claimed the title of most feared activist. In 2022 alone, it launched 13 campaigns. That’s roughly twice the number of its large rivals, including veteran corporate raider Carl Icahn, according to global financial services firm Lazard.

Some of that fear factor stems from Elliott’s size. With US$55 billion in assets under management, it’s large enough to go after big fish (Pershing has US$15 billion). The average market value of its targets is US$24 billion, according to Insightia, which tracks activist campaigns, and in the past Elliott has hit giants like AT&T and GlaxoSmithKline. Last year, the fund bought a 3.4% stake in Suncor.

Elliott also has a reputation for being ruthless. The money manager has multiple divisions, and its hedge fund arm that invests in stocks and other securities once bought Argentinian bonds, leading to a showdown with Argentina’s government. Elliott would not accept the terms of the country’s debt restructuring deals, and the standoff got so ugly that Elliott took Argentina to court in the U.S., then convinced a court in Ghana to detain a 348-foot Argentine navy vessel docked in its port. The fund argued it had a right to take the ship. The boat was eventually released, but Elliott later won a settlement that delivered a nearly 400% return on its investment.

Elliott has also been accused of flashing a six-inch-thick dossier during a meeting with directors of one company that purportedly contained dirt on them and their families, as well as unearthing the old divorce records of a CEO it was hoping to get fired and allegedly leaking them to the media. Elliott has denied these allegations.

Even if such tactics are a thing of the past, Elliott remains cutthroat. Many activists now try to engage boards of directors in private, hoping to reach quiet settlements. Yet, when Elliott went after Suncor, it didn’t even give the board a polite heads-up. Instead, it went public from the jump with a letter addressed to the board that laid out details of its plan to elect five new directors and potentially replace CEO Mark Little (who took over in 2019), as well as explore a sale of Suncor’s retail chain of Petro-Canada gas stations.

Still, the fund doesn’t always get what it wants. Although there’s been a CEO change at Suncor—Elliott appointed three directors in July 2022, and Little was gone the same month—the board declined to sell off Petro-Canada.

In another fight two years ago, the fund went after Scottish energy group SSE, asking management to spin out the company’s renewable energy group. SSE’s top investors shot down Elliott’s requests, then bad-mouthed the fund to The Sunday Times, arguing that its financial analysis was, actually, rather elementary.

The usual suspects

Every year, there’s a steady cast of activist funds that make headlines. Carl Icahn has been at it for decades, dating back to the 1980s, when he rode the wave of corporate raiders and made his name by taking Trans World Airlines private. He struck it rich; only the airline suffered under the debt load. (Funny enough, Icahn is now being targeted by an activist short seller that argues his holding company has inflated the value of some assets. Icahn’s company says it stands by its public disclosures.)

Other reliable actors include Jana Partners, ValueAct Capital Partners and Starboard Value. In the past year, their campaigns have targeted popular companies such as music streaming service Spotify, demanding cost cuts following an unprofitable expansion into podcasts, and New York Times Co., asking management to push subscribers into higher-priced bundles that include apps such as NYT Cooking.

Even though these actors may seem like the usual perennial players, their tactics are evolving, and that means the old defensive tactics won’t always apply anymore. Activists used to make pretty straightforward demands: sell off assets to generate cash and pay down debt, for instance, or issue a special dividend. Lately, though, they’ve tested out new arguments. When Icahn took a run at McDonald’s last year, he sounded more like an ESG advocate than a barbarian at the gate (a term for raiders of the 1980s), calling the corporation’s treatment of pregnant pigs an “obscene cruelty.” But shareholders rejected his board nominees.

Activists have also taken to swarming. There have long been “wolf packs”—groups of activists that work in concert—but recent behaviour is different. Funds in a wolf pack used to talk to each other in advance and launch a co-ordinated attack. When activists swarm, the funds often act independently and sometimes demand wildly different things from management.

Enterprise software giant Salesforce faced such an attack in the past year, battling five different activists at the same time, including Elliott, Starboard Value and ValueAct. In March, Salesforce promised it would focus on profit rather than growth, doubled its share buybacks and created a new division that will work on “business transformation.”

Canadian utility Algonquin Power is also dealing with multiple activists, with Starboard and Corvex joining Ancora in its call for quick asset sales to help pay down debt. Algonquin’s shares are down roughly 40% over the past year. A little more than one-third of all campaigns launched in the first quarter of 2023 were swarming scenarios, Lazard reports, and that figure is expected to grow.

Hedge funds that cosplay as activists

It’s a dizzying time for directors and CEOs. After the signature CP campaign, they were all counselled on what to do if Pershing Square or another prominent activist came knocking. But now it’s not just the usual suspects. Small hedge funds, like San Francisco–based Engine No. 1, which has only US$300 million in assets under management (less than 1% of Elliott’s), can have just as much impact. In 2021, investment giants BlackRock, Vanguard Group and State Street all voted against the leadership of oil giant Exxon Mobil, in line with Engine No. 1.

Veteran activists have trained scores of portfolio managers on the tricks of the trade, and some of them have left the bigger funds to replicate these strategies at smaller shops. When Engine No. 1 made global headlines by prompting that shakeup of Exxon’s board, the battle was framed in the media as David versus Goliath. What got lost in that narrative is that Engine No. 1 had hired Charlie Penner, a former managing director at Jana Partners, to run the campaign.

In Canada, two hedge funds have taken on established real estate investment trusts already this year: K2 at H&R REIT and Ewing Morris at First Capital REIT. Both fights were pretty benign in the end, with settlements that saw a total of five new trustees named to the boards of the REITs, none of which came from the slates of trustees proposed by the hedge funds. But these attacks can be quite challenging because no one ever knows if a small fund has a much bigger fish behind it.

Ryan Garcia/The Globe and Mail

To be an activist, an investor needs to be a bit brash. It’s the best way to grab the attention of other shareholders, because it’s tough to take a stand against management. But confrontation may not jibe with the internal culture of a traditional fund, particularly large, established ones that have holdings in many leading companies and form long-term relationships with the management teams that run them.

Conflicts of interest are also a common hurdle. Royal Bank of Canada’s asset management arm, for instance, is one of the largest institutional investors in the country and therefore a top shareholder at many large Canadian companies. But these same companies may be clients of RBC’s investment banking arm, which gets hired to defend against activist funds. RBC can’t fight RBC. (The bank says it has stringent internal controls to guard against any conflicts of interest.)

To skirt these issues, an institutional investor who’s fed up with management can put out an RFA—a request for activism—and bring on a smaller fund as a hired gun. When they do, it can throw all norms out the window. It used to be that if a small fund owned only a tiny percentage of a company’s stock, the fund might be laughed at for trying to make changes—especially if it had only recently bought the shares. These campaigns were seen as attempts to make the share price pop, and then the funds would sell shortly afterward.

But these days, it’s entirely possible that a small fund is a front for major shareholders—not unlike a new-age Trojan horse.

So, what’s a board chair to do?

To start: Never, ever underestimate anyone who knocks on the door. If an activist’s demands are ludicrous—and they sometimes are—shareholders will eventually see through them. But don’t be dismissive from the get-go.

Second, prepare now, even if there weren’t any skirmishes during the current proxy season. Activists have learned they’re more likely to win support from other investors if they can show they’ve tried to engage management and directors for months. Boards that skated through this year will want to relax, but there won’t be much of a lull. Private discussions often start in the fall, and disgruntled shareholders like to pounce when boards least suspect it.

The bottom line: The activists are coming, and they can’t be ignored.

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.