Welcome to Report on Business magazine’s 40th year in print. Corporate Canada has undergone some seismic shifts since we launched the inaugural Top 1000 list in June 1984. We asked ROB contributors past and present to write about some of their favourite stories and the people behind them.

1984

The launch issue of Report on Business magazine in 1984.

It was a little over 40 years ago that the genteel world of corporate finance in Canada was turned on its head. The great disruptor of the day? The small brokerage firm Gordon Capital—long scorned by Bay Street’s old boys’ club—and its outsize, impossible-to-ignore captain, Jimmy (the Piranha) Connacher.

The firm’s wildly lucrative creation was the bought deal, in which it would buy all the new stock or debt from an issuer, while assuming all the risk of finding buyers—an innovation that permanently transformed the way financings got done in Canada.

It also showered Gordon Capital’s tight-knit group of partners with riches and launched a thousand legendary tales of boozing, womanizing and partying to match its reputation for hard work—from the private butler, Basil, delivering scotch to traders at their desks so they could keep working the phones, to Connacher’s infamous appearance at a Christmas party wearing nothing but a string of lights, to the time two female secretaries received breast implants as bonuses.

This was the world Report on Business magazine was born into, and in the decades since, the face and pace of Bay Street has changed to an astonishing degree.

To mark the start of ROB’s 40th anniversary year, and to trace the evolution of corporate Canada over that time, we set out to identify the 40 people (and the events and trends they sparked) that have shaped Bay Street since our first issue rolled off the press—through booms, bubbles and busts, ambition and achievement, disappointment and ruin.

The personalities have certainly changed. After regulators briefly banned Connacher from the investment industry in the early 1990s, Gordon Capital stumbled into obscurity, but its alumni went on to top jobs across Bay Street.

Other larger-than-life trading giants have overshadowed their own eras, like Lawrence Bloomberg in the 1980s and ‘90s, followed by Mike Wekerle at GMP Securities. Though in today’s bank-dominated markets, the traits that once defined a star trader, like instinct and bravado, have largely given way to algorithms and high-frequency transactions measured in nanoseconds.

The world has presented many moments of crisis and opportunity along the way, from war to pestilence to recession, while the very contours of power have shifted technologically, geographically and politically—events and trends that have made Bay Street what it is today.

– Jason Kirby

War on fees

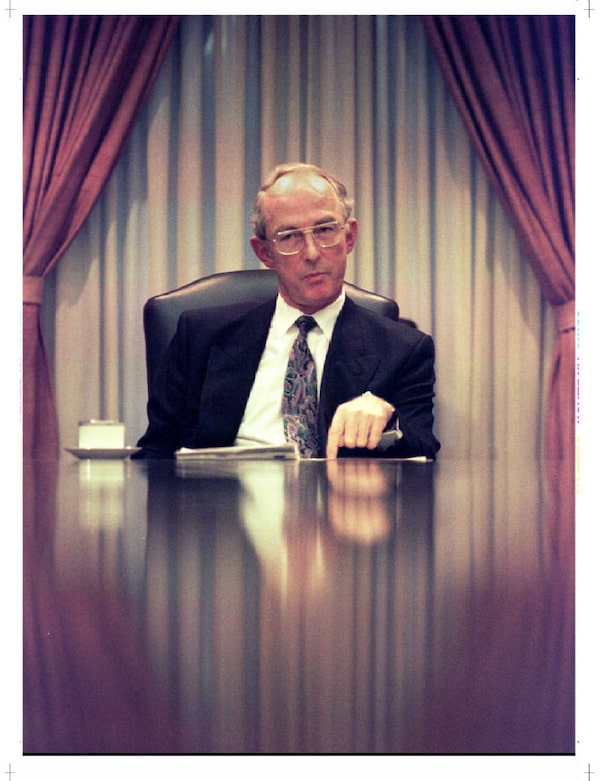

Dick Thomson

Dick Thomson, at NEXEN's annual general meeting in Calgary, Alta., in April 2005.The Globe and Mail

Visiting a stockbroker in the early 1980s was like dropping by a frat club for middle-aged men: wood panelling, leather sofas, sports chatter, and lots of well-dressed brokers dispensing hot tips and loud jokes.

How did stockbrokers manage to support this non-stop party? Outrageous fees. For a typical investor, the commission for either buying or selling a stock was around 2.5% of the order’s value. Think about that for a second: You had to make 5% on your investment just to break even.

In many ways, the story of Bay Street over the past 40 years has been the story of how that cozy world of fat fees and backslapping bonhomie has been replaced by a new regime of low-fee, mass-produced financial products. The initial impetus came from the U.S., where institutional investors had long objected to stockbrokers’ lush commissions. The NYSE finally agreed to abolish fixed minimums in the mid-1970s. Suddenly, brokers had to do what was once unimaginable: compete on price.

In 1983, Ontario followed suit and deregulated brokerage commissions. The following year, TD Bank, then the smallest of the Big Five and led by Dick Thomson (who not only had a bachelor’s degree but a Harvard MBA—a true rarity in that era), launched a discount brokerage service called Green Line. Customers flocked to take advantage of its bargain prices—$29.95 a transaction, regardless of volume. By 1987, Green Line had attracted more than 100,000 clients.

When Ottawa passed legislation that allowed Canadian banks, trust companies and insurers to acquire investment dealers, the banks sought to build new empires in the investing business. They wanted to keep the full-service brokers’ traditional clientele of wealthy families, but they saw even greater potential in expanding their discount brokerages and other mass-market products to cater to a middle-class clientele—and that meant pushing fees relentlessly lower.

The public enjoys a much better, much more transparent deal these days. Newbie investors can open accounts at a discount broker, and in a few seconds buy a superbly diversified portfolio of global stocks and bonds. And they can comfortably count on holding that indexed portfolio for years while paying an all-in cost barely above zero.

The downside? Nobody goes to visit their stockbroker any more, which means you have to go elsewhere for your hot tips and sports chatter. Bay Street isn’t nearly as colourful or as personal as it was 40 years ago. It is, however, a much better deal.

– Ian McGugan

Buyout king

Gerry Schwartz

Schwartz, whose name is invariably preceded by the moniker “buyout king,” pioneered the leverage takeover deal in Canada in the 1980s, building the private equity firm Onex into a $7-billion company through scores of acquisitions—most recently, the high-profile deal for WestJet in 2019.

As Edward Greenspon wrote in “The Acquisitor” in October 1987: “Since setting up shop in Toronto four years ago, Gerry Schwartz has come to be regarded as one of the ablest of a new generation of Canadian business people. ...He believes that good performance depends on genuine participation—a belief rooted in pragmatism, not egalitarianism.”

An exhausted trader slumps in his chair at the Toronto Stock Exchange on Oct. 19, 1987, a day that has come to be known as Black Monday.TIM CLARK/CP

Black Monday

Panicked investors

Well before the market opened on Oct. 19, 1987, the tension was thick on the floor of the NYSE. The trading days leading into the weekend were disconcerting. After a five-year bull run, the inevitable correction had arrived. Overseas markets were in a panic. Selling pressure was building. As soon as the opening bell sounded, the crash was underway. Waves of sell orders sent stock prices into freefall, which in turn triggered computerized trading programs to generate more sell orders, compounding the losses. By the close of trading, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was down by 22.6%—a record single-day toll that stands to this day.

What became known as Black Monday represented a new kind of market meltdown, with global markets crashing more or less in unison. Recognizing that financial liquidity, rather than economic stress, was at the core of the problem, the Federal Reserve injected billions of dollars into the financial system by buying up Treasuries. This essentially remains the policy playbook today, written when Black Monday set the precedent for the modern global financial crisis.

– Tim Shufelt

Big spender

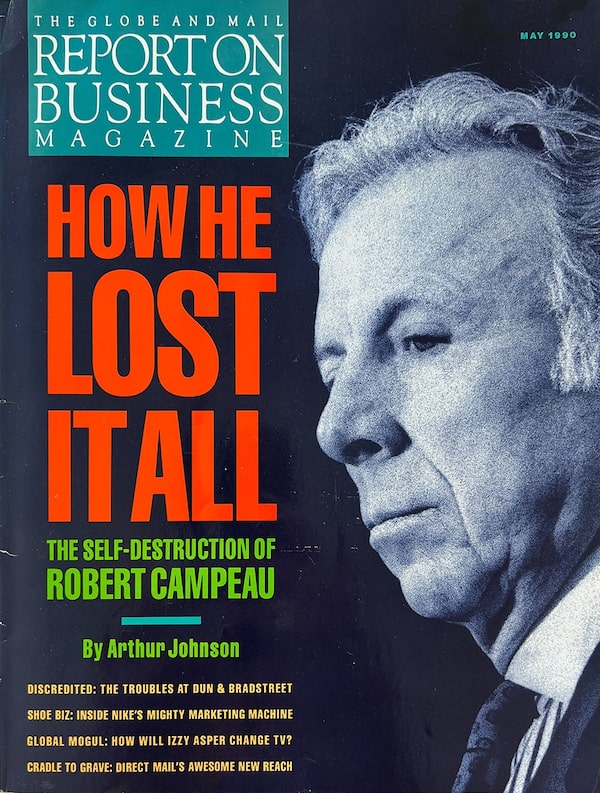

Robert Campeau

From penniless Northern Ontarian to Ottawa real estate tycoon to U.S. retail financier, Campeau’s ambition and appetite for debt propelled his rise during the 1980s to department-store kingpin, briefly controlling chains like Bloomingdale’s after spending US$10 billion on acquisitions. When reality hit, his empire collapsed. As Arthur Johnson wrote in his May 1990 profile: “He was unpredictable, often saying one thing and doing the opposite.

Then there were the interesting personal bits—the face lifts, the hair transplants, the nervous breakdowns after business setbacks in Canada, the psychiatrist who sat on the board...the terrible feuds and lawsuits with two of his oldest children. These things made a lot of people nervous. But Campeau had also made more than a few people rich.”

Robert Campeau on the cover of the May 1990 issue of the magazine.The Globe and Mail

Brokerage bonanza

Michael Wilson

Canada’s financial sector during the “greed is good” era looked a whole lot different. The banks stored and lent money; investment banks were independent shops that advised on mergers and traded stocks and bonds. That all changed at the tail end of the Reaganomics era starting in the U.K. with Margaret Thatcher lifting the ban on U.K. lenders getting into the investment banking business. It wasn’t long before the Big Bank CEOs here in Canada were knocking frantically on federal finance minister Michael Wilson’s door, begging for the same leave.

In 1987, Wilson delivered, and within a year many of the best-known indie investment banks were gobbled up. Bank of Montreal moved first, snapping up Nesbitt Thomson. It was followed by Royal Bank buying Dominion Securities, Scotiabank acquiring McLeod Young Weir, and so on. (The sole holdout was TD Bank, which built its own brokerage in-house.)

The indies feared it would put an end to their cowboy way of life—not to mention restrict them from personally investing in companies they did business with. (“Conflict of interest” was not a thing at the Gordon Capitals of Bay Street.) But that wave of consolidation arguably made it easier for some of them to survive Black Monday and the nasty recession of the early ‘90s.

Former Finance Minister Michael Wilson on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Feb. 3, 1986.Charles Mitchell/The Canadian Press

For those that did or came later—including Canaccord Capital, FirstEnergy and GMP Securities—the next few commodity booms were glorious. The real demise started after the 2008 global financial crisis, following one last rager, when China’s stimulus money sent commodity prices soaring.

Now, as the banks expand their capital markets and wealth management businesses, fears are growing that they’ll abuse their dominance. (Indeed, the Ontario Securities Commission fined RBC just $1.1 million for paying some advisers a better commission to sell the bank’s own funds between 2011 and 2016.) The independents still kicking around complain that the watchdogs ought to do more. But it’s complicated. Those added revenue streams make the banks more stable in times of crisis. And if the past 15 years have taught us anything, it’s that Earth-shattering crises are now a regular occurrence.

– Tim Kiladze

Canadian Tire feud

The Billes Clan

Stan Beck, the chairman of the Ontario Securities Commission at the time, drily referred to it as “the OSC’s very own Christmas pageant.” In September 1986, the inner workings of Canadian Tire had been revealed as a cross between a Dickens novel and a WWF cage match. The beloved and tidily managed chain of automotive hardware stores that tracked the rise of the car and suburbia in Canada, and made millionaires out of many of its stock-owning employees and nearly all its dealers, was a mess.

The smackdown starred the previously invisible Billes clan—co-founder A.J. Billes (the model for Sandy McTire, the thrifty Scot depicted on Canadian Tire “money”), his hothead son Fred (who owned the flagship store in downtown Toronto) and his coolly eccentric sister Martha. They were suddenly slugging it out in public, sometimes even physically. Martha, Fred and their brother David had inherited (much to A.J.’s later regret) a majority of the company’s dual-class voting shares, which gave them 60% control with only 4% of the company’s equity. Fred and Martha each felt they ought to be running the operation and hated the thought of the other anywhere near the controls. Martha accused Fred of being fat and alcoholic, while Fred accused Martha of being a ditz and a cheapskate.

Canadian Tire shareholder Martha Billes smiles for a Calgary Sun photographer as she leaves a Calgary courthouse on March 29, 2000.Jeff McIntosh/The Globe and Mail

Fed up at last, the siblings decided to sell their shares to Canadian Tire’s network of dealers, who were no match for the small, exclusive club of bamboozling Bay Street securities lawyers (29 in all) who descended on the deal like a flock of well-dressed vultures. The transaction turned on the legalistic interpretation of a single sentence that required any change in majority ownership to profit non-voting shareholders as well as the family. The ensuing pre-Christmas OSC hearing made and broke dozens of reputations, humiliated the dealers as bumpkins and rubes, cracked the Billes family in two, demolished the company’s reputation as a well-managed paragon, and resulted in Stan Beck blocking the deal as “a flagrant abuse of the marketplace.”

That didn’t stop Fred and David from later selling their shares. (Martha stayed on as a board member.) Nor did the legal ruling eliminate dual-class shares, still commonly used to protect hereditary wealth against the enrichment of the many. “It’s better than Dynasty,” one of the lawyers noted at the time. But what the whole sad fracas really resembled was Dogpatch.

– Ian Brown

Plus four other famous family feuds...

Magna International Inc. Founder and Chairman Frank Stronach and his daughter Belinda Stronach, now Magna chairman, CEO and President, at the company's AGM in May 2009.Mike Cassese

The Irwins (1999) In a bid to move away from family control, George Irwin canned a trio of relatives, then abruptly resigned soon after. A year later Irwin Toy was sold to a private investment group; 18 months after that, it declared bankruptcy.

The McCains (2004) Harrison McCain ousted his little brother Wallace over who’d succeed them as CEO. Wallace and son Michael went on to buy Maple Leaf Foods, while a non-family CEO was installed at McCain, against Harrison’s wishes.

The Stronachs (2020) Magna founder Frank filed suit against his daughter Belinda and her kids, alleging she’d mismanaged his fortune.

The Rogers family (2021) This internecine battle pitted Edward Rogers against his mother and two sisters, split the board, and led the ouster of CEO Joe Natale and the replacement of the majority of its independent directors—all in the midst of its $20-billion takeover of Shaw.

Comeback Queen

Veronika Hirsch

Veronika Hirsch in November 2007. Hirsch appeared on the magazine's cover twice – once in November 1996, and again in February 2012, for our annual Invest Like a Legend issueKevin Van Paassen/The Globe and Mail

It’s hard to believe now, but when Fidelity Investments lured away then 41-year-old fund manager Veronika Hirsch from AGF—which over 10 short months had invested roughly $2 million to make her a household name—the move was “greeted with the type of fanfare one associates with million-dollar sports trades,” Anne Kingston wrote in her November 1996 cover story. “It was the third item on that evening’s CTV National News. She was referred to as ‘the biggest name in mutual funds.’”

Just a few months after Hirsch made the jump—and while her face graced that month’s issue of ROB—her career exploded over a personal trade in a junior mining company. By the time she appeared on ROB’s cover again, in February 2012, she’d more than redeemed herself—it was our annual Invest Like a Legend issue.

O&Y collapse

Paul Reichmann

Paul Reichmann of Olympia and York Developments Ltd., on Oct. 17, 1985.John McNeill/The Globe and Mail

Paul Reichmann and his partner/brother Albert were on a roll. Having emigrated to Canada in the early 1950s, the family built a decorative tile business that spawned a property development company called Olympia & York. Under the two brothers, O&Y went on a gravity-defying ride. The family built downtown Toronto’s First Canadian Place in 1975, the biggest office structure in Canada. It pulled off the “deal of the century” in 1977 by scooping up a parcel of buildings in lower Manhattan amid the dysfunction of a destitute New York. It erected that city’s World Financial Center in 1980.

Looking beyond North America, it was a natural partner for Margaret Thatcher, whose transformation of Canary Wharf in London came with promised financial incentives, including a rail connection.

But by the late 1980s, the global property market had crashed. Thatcher could not deliver the crucial transit link when expected. O&Y’s banks had enough. In March 1992, O&Y plunged into bankruptcy, at that time the biggest corporate failure in Canadian history. Canary Wharf would be completed by others.

Paul Reichmann scrambled to win back control of his baby but lost it again, writing a finale to his epic career.

In time, Canary Wharf would flourish as the new centre of financial power in London. Major banks flocked to the site, confirming the vision of Thatcher and Reichmann, who both died in 2013. Yet even today, it is a barometer of its times, its future now clouded by Brexit and remote work. It seems ripe again for a contrarian like Paul Reichmann.

– Gordon Pitts

Kiki Delaney, CEO and president of Delaney Capital Management, the investment firm that she founded in 1992.Charla Jones/The Globe and Mail

Trailblazer

Kiki Delaney

Kiki Delaney has the brokerage business in her blood. Her currency-trader dad founded his own firm in Winnipeg, and she got her start as a sales assistant at Merrill Lynch Canada in 1970. A couple of years later, she moved to Toronto to join Guardian Capital as a stock analyst (where, she once told Globe and Mail reporter Jacquie McNish, she compensated for the “loneliness” she felt as a rare woman in the business by working long hours to uncover undervalued investments).

Gluskin Sheff lured her away as a partner in 1985, and seven years later, she set up her own shop, Delaney Capital Management, where she remains and where her best investment, as we pointed out in our February 2019 Invest Like a Legend issue, was buying Constellation Software stock at $17—it now trades around $2,780. In 2001, she was elected president of the elite Ticker Club, a Bay Street club created in 1929 that attracts the cognoscenti of Canada’s money managers with assets under management in the trillions of dollars.

Five memorable Big Bank CEOs

From left, Matthew Barret, Gord Nixon, W. Edmund Clark, John Hunkin, and Peter Godsoe.Peter Jones/The Globe and Mail, Fred Lum/the Globe and Mail, Graham Hughes/The Canadian Press, Robert Tinker/The Globe and Mail, Kevin Van Paassen/The Globe and Mail

Matthew Barrett, Bank of Montreal, 1989-1999

Canada’s first celebrity banker. He oversaw BMO’s hip “Can a bank change?” ad campaign, even though he didn’t particularly like it.

W. Edmund Clark, TD Bank, 2002-2014

Ran Canada Trust until TD bought it in 2000, then ran the bank and built it into a retail powerhouse. A staunch Ontario Liberal, he’s still a consummate networker.

Gord Nixon, Royal Bank of Canada, 2001-2014

Chose to grow RBC steadily, rather than make flashy acquisitions. “When a CEO starts talking about his legacy, it’s time to short the stock,” he told Eric Reguly.

Peter Godsoe, Scotiabank, 1993-2003

Traditionally the most international of the Big Five banks and the smallest. When he retired, he boasted, “We’re not only second, we’re the second-largest company in the country.”

John Hunkin, CIBC, 1999-2005

He pushed the bank on to Wall Street and into risky loans to telecom companies and Enron. “I’ve had more difficulties than some,” he conceded. Still, he did double the stock price.

Seagram’s demise

Edgar Bronfman Jr.

For decades, Montreal-based Seagram was a golden company, built by Sam Bronfman (who once famously said, “I don’t get ulcers, I give them”) and family from Prohibition rum-running to custodians of a glittering portfolio of booze brands like Chivas, VO and Crown Royal. On the first-ever Top 1000 list in 1984, it ranked third in terms of profit, behind only BCE and Royal Bank of Canada. Sam’s sons Edgar and Charles added a steady cash-earner from a large stake in chemicals icon DuPont.

It all worked until the third generation: designated successor Edgar Jr., a media dilettante who penned pop tunes. He took Seagram boldly into entertainment, making multibillion-dollar bets on movie production and a record label, while divesting the DuPont cash cow. That made him a natural target for Jean-Marie Messier, a thrusting French conglomerateur determined to assemble a media-convergence showpiece out of an old-economy water utility.

Edgar Bronfman Jr., then President and CEO of Seagram Co., delivers a speech to the Canadian Club in Montreal, on March 8, 1999.Shaun Best/Reuters

In June 2000, they concocted a deal in which Messier’s Vivendi would acquire Seagram in a $33-billion all-stock takeover, and then dispose of the legacy drinks business. The Bronfmans would end up as Vivendi’s largest shareholders; Edgar Jr. would be a star player in the new Vivendi Universal.

Messier went on a spending orgy, loading on more and more debt. Markets soured on his ego-driven grand project. The Bronfmans ousted Messier, but not before he’d frittered away a large chunk of their wealth.

Today, Seagram is a footnote, its brands split among drinks giants. Vivendi is a nothing-special French media company. Edgar Jr. is a private equity guy in New York.

His uncle Charles described the sad chapter this way: “It was a disaster, it is a disaster, it will be a disaster. It was a family tragedy.”

– Gordon Pitts

TSX transformation

Rowland W. Fleming, former President and CEO of the Toronto Stock Exchange, meets the press in the TSE boardroom in January 1995.Mike Blake/Reuters

Rowland Fleming

The trading floor of the Toronto Stock Exchange was once an eardrum-assaulting gaudy mess of colourfully jacketed floor traders (green for TD, red for Nesbitt Burns and so on) screaming their trades at one another across the cavernous room.

That all ended on April 23, 1997, when the TSX—under the direction of president Rowland Fleming, who very soon would come under fire for his handling of the Bre-X fiasco—shifted to an infinitely quieter electronic system, making it the first North American stock exchange to ditch “open outcry” trading. (Fully digital trading had been possible for Toronto brokerages since 1992.)

The physical trading floor closed almost exactly a year after the TSE adopted decimalization, allowing stocks to rise or fall by increments of a single cent (and, later, by even less than a cent), replacing the former fractions-based pricing model where the smallest price change was one-eighth of a dollar. The combination of digitization and decimalization paved the way for the rise of modern practices like high-frequency trading, which became increasingly common as computing power advanced over the following decades. In the early 2000s, a high-frequency trade would still have taken several seconds to execute; by the early 2020s, that had fallen to a few nanoseconds—one-billionth of a second.

– Jameson Berkow

John B. Felderhof, David Walsh and Paul Kavanagh at the Bre-X annual meeting on March 14, 1996.Edward Regan/The Globe and Mail

Bre-X bust

John Felderhof & David Walsh

On May 5, 1997, American mining giant Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold issued an announcement that ended weeks of speculation about the fate of Canadian exploration company Bre-X Minerals. The release confirmed that independent drill tests at Bre-X’s Indonesian gold site showed “no samples that have gold values of economic interest.” Even worse, Freeport said Bre-X’s own results “resulted in falsification and misrepresentation of many thousands of samples,” leading to “erroneous estimates of gold resources.”

Freeport’s revelations were the final confirmation that Bre-X—headed by Calgary mining promoter David Walsh—was the world’s biggest mining fraud, a brazen salting scheme that saw employees at the remote Busang site sprinkle gold flakes into drill samples. At their peak in 1996, Bre-X shares were worth $6.2 billion. After Freeport’s announcement, they were worthless.

Bre-X’s problems had kicked off that March, with the news that site geologist Michael de Guzman had died of an apparent suicide after falling from a helicopter on a return trip to Busang, where angry Freeport officials were waiting for him to explain puzzling test results. (Conspiracy theories abounded for years, suggesting a badly damaged body recovered in the jungle may not have been de Guzman’s and that he may still be alive.)

The fallout changed everything for Canada’s mining community, marking the end of an era that had made Canada a mecca for mining companies to raise money with the help of promoters who touted stocks like carnival buskers.

Bre-X Mineral's former chief geologist Michael de Guzman (second from right) conducts a survey at the Busang-2 field on Borneo island, in March 1997, shortly before his death.The Associated Press

Canada had no choice but to crack down, recalls Maureen Jensen, a Toronto Stock Exchange executive appointed in 1998 to help draft new disclosure and testing standards for the mining industry. (She would later serve for four years as head of the Ontario Securities Commission.) In the wake of Bre-X, “no one could raise any money—no one wanted to be involved with mining companies after that fiasco.”

The task force recommendations focused on new practices for on-site exploration and drilling, stricter rules for reporting findings to shareholders, and required companies to have their results publicly certified by a licensed engineer or geoscientist with experience analyzing the specific type of resource involved. “So you can’t just have a promoter saying, ‘I found a million-ounce deposit,’” says Jensen. Other rules took aim at analysts who touted shares while not disclosing that their companies acted as underwriters.

No one was ever convicted for their role in the fraud, a black eye that still haunts Canadian regulators. Walsh died suddenly in 1998 before police and regulatory investigations were completed. John Felderhof, the Canadian chief geologist who directed on-site work in Indonesia, was accused by the OSC of knowingly issuing false press releases while cashing out millions of dollars in stock options. He argued he knew nothing of the salting activity and was acquitted in 2007 after a lengthy trial. He died in 2019.

As regulators worked to restore Canada’s reputation, they stressed that their new mining disclosure standards were the strictest in the world, and many of them have since been adopted in other countries. Bre-X, says Jensen, “had a huge global impact.” Despite the new rules, she says the world could still see a repeat, “but it would require a lot of people—a lot of people—lying.”

– Janet McFarland

Bay Street killjoys

Paul Martin & Jim Flaherty

Former Finance Minister Paul Martin in December 1998.Fred Chartrand/The Canadian Press

Former Finance Minister Jim Flaherty in March 2010.GEOFF ROBINS/The Canadian Press

In most of the ways that matter, Paul Martin and Jim Flaherty were a study in contrasts as finance ministers. Martin inflicted the most severe spending cuts in decades, while the career Conservative politician Flaherty embarked on the most epic government spending binge in, well, decades. Yet there’s one role each played that has left an indelible mark on Bay Street: spoilers to the party.

For Martin, it was the December 1998 decision to kibosh the marriages of RBC to Bank of Montreal, and TD to CIBC, less than a year after the financial giants announced the megamergers. The result forced Canada’s Big Banks to find other ways to grow—and arguably put the country’s financial sector on firmer ground to survive the global financial crisis a decade later.

For Flaherty, it was his move in October 2006 to place a tax on income trusts, pulverizing a frenzied trend that saw companies rush to convert themselves to trusts so they could pay out most of their cash flow to investors and avoid taxation themselves. Retail investors resented the move, as did Bay Street bankers and lawyers who collected fat fees from trust conversions, but they also disincentivized companies from investing their capital in their own growth.

Two bold moves that in time looked right—even if they weren’t popular.

– JK

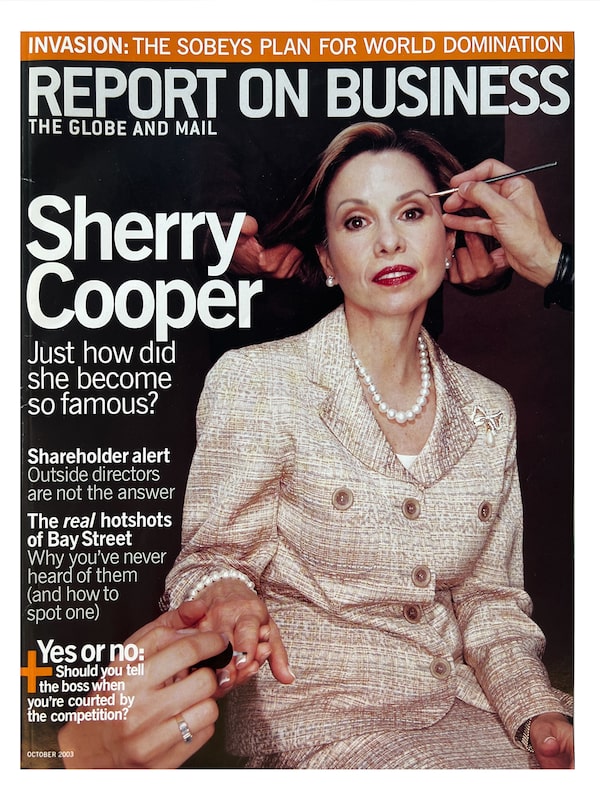

The October 2003 cover of the magazine showcased Bay Street finance legend Sherry Cooper.The Globe and Mail

Rise of the celebrity economist

Sherry Cooper

A former Fed official, Cooper moved to Canada in 1983 to become chief economist at Burns Fry, then one of the largest indie brokerages in Canada. In 2006—Burns Fry long since having been swallowed by Bank of Montreal—Cooper, with her knack for making economics accessible and an easy manner in front of the camera, became the second woman to be named chief economist of a Big Bank. The first was Helen Getter, who was appointed chief economist of TD Bank in 1994.

BlackBerry changes the world

FRom left, co-CEOs Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie at their Waterloo Research in Motion (RIM) lab in in May 1999.RICK KOZA/KIT

Jim Balsillie & Mike Lazaridis

The BlackBerry quietly debuted 25 years ago, in September 1998, at a conference in Boston. Salespeople from Waterloo’s Research In Motion buzzed around, looking for corporate warriors with ungainly communications devices strapped to their belts, then pulling out the as-yet-unnamed BlackBerry—the size of a pager, with a monochrome four-line screen and a tiny keyboard—to show them a better way. The device gave users instant access to email, and it quickly became a must-have for investment bankers, lawyers, CEOs and world leaders, who interrupted family dinners, graduation ceremonies and deep sleep to broker deals, fend off hostile takeovers and trade in gossip.

As Nortel collapsed, RIM became the hottest gadget-maker not just in Canada but in the world. It was even, briefly, Canada’s most valuable company, and it made co-CEOs Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie billionaires and household names. More than that, RIM transformed its hometown into Canada’s tech hub (sorry, Ottawa) and forever changed the way human beings communicate. For better or worse, the BlackBerry made all of us always on (the clock) and always connected (to work). It set the stage for Apple and Google to launch next-generation no-keyboard touchscreen phones that fully connected people to the internet—and turned BlackBerrys into artifacts.

– Sean Silcoff

From left: Barbara Stymiest, Laura Dottori-Attanasio, Janice Fukakusa, Joanna Rotenberg, Jill Denham, Sonia Baxendale, Teri Currie, Colleen Johnston, and Rania Llewellyn.Tibor Kolley/The Globe and Mail, supplied, Tijana Martin/The Globe and Mail, Cole Burston/The Globe and Mail, Darryl James/The Globe and Mail, supplied, Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail, supplied, and O'Shane Howard/The Globe and Mail.

The women who came this close to becoming the first female Big Bank CEO

Barbara Stymiest: RBC lured the TMX Group CEO in 2004; she was then seen as a successor to Gord Nixon. Instead, she shocked everyone by retiring at the end of 2010.

Laura Dottori-Attanasio: One of CIBC’s top execs left in January 2023 after 14 years to become CEO of Element Fleet Management.

Janice Fukakusa: She spent 31 years at RBC, with a good chunk as chief admin officer and CFO. She retired in 2017 and became the first female chancellor of what was then Ryerson University.

Joanna Rotenberg: BMO’s head of wealth management left in 2021 to lead Fidelity Investments’ US$4-trillion personal investing division.

Jill Denham: CIBC’s head of retail banking was shuffled out in 2005 as Gerald McCaughey took over as CEO. She went on to serve on several boards and launched her own firm.

Sonia Baxendale: Was president of CIBC Retail Markets until 2011, when the bank rejigged the top ranks. She went on to become CEO of the Global Risk Institute in Financial Services.

Teri Currie: She spent 35 years at TD, most recently as head of Canadian retail banking, before retiring in 2021. She was succeeded by a man.

Colleen Johnston: Joined TD in 2004 after years in senior roles at Scotiabank and became CFO a year later, a post she held for a decade. She retired in 2018 and sits on many boards.

Rania Llewellyn: The Kuwaiti-born former Scotia exec became the first woman to lead a major chartered bank in Canada, Laurentian, in 2020.

Nortel nightmare

John Roth

John Roth, CEO of Nortel Networks an inductee into the 2001 Business Hall of Fame in December 2000.Peter Tym/The Globe and Mail

Long before there were meme stocks, FANGS and NFTs to whip investors into a frenzy, there was Canada’s most inauspicious contribution to the “irrational exuberance” of the dot-com and telecom bubble era. Between early 1999 and September 2000, under the direction of CEO John Roth—an electrical engineer who’d joined the company in 1969, back when it was still known as Northern Electric—investors bid up Nortel’s value nearly six-fold, driven by greed, yes, but also blind optimism in the unlimited demand for internet bandwidth, and with it, the fibre-optic network gear Nortel made and sold. There’s not been anything like it in scale since. At its peak, Nortel’s market capitalization soared to $360 billion. A generation later, that’s still more than the market value of Canada’s two largest companies, Royal Bank and TD Bank, combined.

Even if an investor didn’t want to ride the doomed Nortel rocket, many were unwilling stowaways. The company’s staggering valuation gave it an outsized share of the TSE 300 index, the precursor to today’s S&P/TSX Composite. Nortel alone accounted for more than one-third of the index’s value. That meant passive index investors were heavily exposed to Nortel, but all too many actively managed funds also loaded up on telecom shares to avoid irate calls from investors.

Nortel wasn’t alone. Shares in any company involved in the network space exploded, including U.S. rivals like Cisco Systems and Lucent Technologies, both of which Roth was obsessed with outflanking on the innovation, acquisition and market-cap fronts. And more companies rushed to capitalize on the action, with 360networks boasting the largest tech IPO in Canadian history at the time, in April 2000. (A little over a year later, it would be in bankruptcy protection.)

To some extent, the global telecom bubble was the respectable older sibling to the dot-com bubble, the explosion in investment in speculative internet companies that blended dubious, profitless business plans with wild growth projections. Even after those loopy dot-coms crashed in March 2000, investors kept bidding up telecom shares like Nortel until the game ended that September.

It was all downhill from there. By 2002—roughly 65,000 layoffs later—most of that vast Nortel wealth had been wiped out, taking with it the life savings of many investors and Nortel employees, not to mention the reputations of stock analysts and fund managers who got caught up in the giddy belief that Old Economy rules no longer applied. Roth was ejected in November 2001, and Nortel limped along under a rotating cast of CEOs before finally being put out of its misery with a bankruptcy filing and mass liquidation of assets in 2009. The crater in Canada’s tech sector took years to fill.

The irony, of course, is that internet traffic did explode the way Roth and other telecom CEOs promised investors it would, and their massive overinvestment in high-speed networks paved the way for today’s internet-of-things economy, the metaverse, crypto and artificial intelligence.

– JK

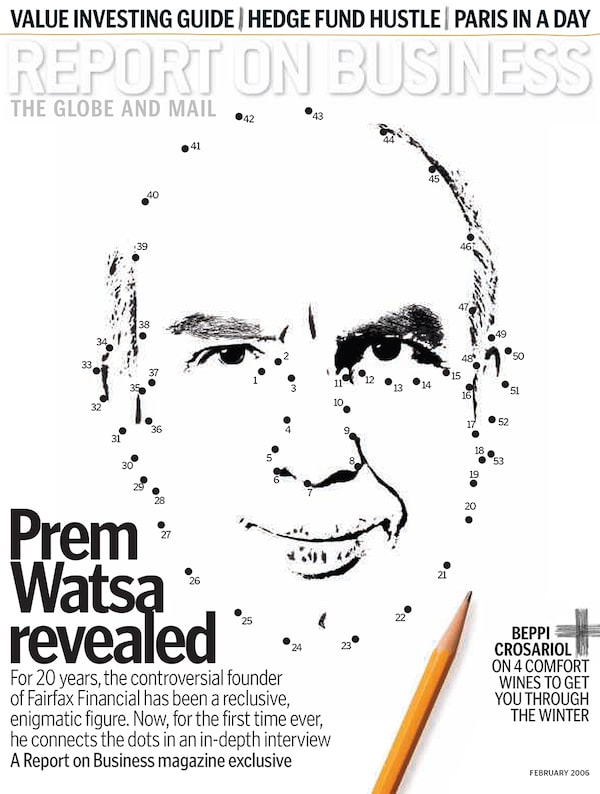

Prem Watsa was featured on the cover of the magazine's February 2006 issue.The Globe and Mail

Rise of value

Prem Watsa

Value investing is an inexact science—you try to buy stocks that are underpriced relative to their intrinsic value. But Prem Watsa acolytes often wait years for his Fairfax Financial Holdings Ltd. to outperform. When we profiled him in 2006, Watsa was under siege from short sellers. But we named him CEO of the year for 2008 after he made $2 billion on wily trades during the financial crisis, and lately, Fairfax shares have soared to all-time highs.

Convergence mania

Jean Monty & Izzy Asper

Jean Monty, former CEO of Bell Canada Enterprises in February 2001.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Israel "Izzy" Asper, former Executive Chairman of Canwest Global Communications in 1999.The Globe and Mail

Woe be the turn-of-the-millennium media CEO who didn’t have a convergence strategy, the fusion of content—news, movies, TV shows, music—with technology to satisfy insatiable consumer demand online. This was, after all, several years before social media titans turned everyone into their own content creator, when entertainment gatekeepers still had a lock on the world’s eyeballs.

In January 2000, dial-up king AOL paid US$165 billion to buy Time Warner, the cable operator and owner of a multitude of entertainment assets. In short order, corporate Canada—led by Jean Monty and Izzy Asper—joined the chase. Under Monty, BCE acquired CTV and (for a time) The Globe and Mail to create Bell Globemedia. Asper’s Canwest Global, meanwhile, absorbed the Southam newspaper chain for $3.2 billion.

What was missing was any semblance of a plan for how this was all supposed to work: how to cross-sell ads across disparate platforms and how to even begin paying down the debt that underpinned those deals.

What followed was the great convergence unwind, the writedowns (AOL, US$54 billion; BCE, $500 million; Canwest, $1 billion), the resignations (Monty from BCE), the bankruptcies (Canwest in 2009), the asset sales and layoffs.

The repercussions are still being felt. The money-losing Postmedia newspaper chain has slashed newsrooms to the bone as its struggles under a $280-million debt, a legacy of the Canwest bankruptcy, while BCE, which bought full control of CTV in 2010 for $1.3 billion, recently cut 1,300 jobs and shuttered its foreign bureaus and several radio stations.

– JK

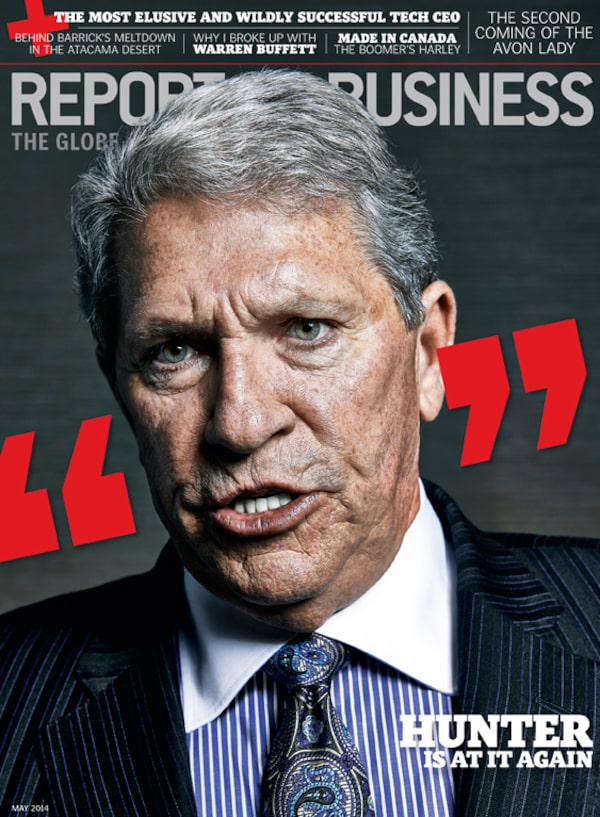

The cover of the May 2014 issue featured Hunter Harrison of CN Rail.Dermot Cleary/The Globe and Mail

Track star

Hunter Harrison

In 2008, we named the delightfully gruff Memphian Hard-Ass of the Year after he turned CN Rail into the best-managed railway in North America. In 2012, he did the same at CP. As he told Gordon Pitts in this May 2014 cover story: “When you go to a new location, in a railroad or whatever, you’ve got to find the meanest son of a bitch and whip his ass—you get a lot of attention,” he says. “You take care of the big bully and a lot of things come together.” Harrison died a railroading legend in 2017.

Livent fraud

Garth Drabinsky

Garth Drabinsky leaves the courthouse amongst a sea of journalists in March 2009, after being found guilty of fraud and forgery at Livent Inc.Charla Jones/The Globe and Mail

Longtime partners Garth Drabinsky, left, and Myron Gottlieb at the Dora Mavor Moore Awards ceremony in 1993.Peter Tym/The Globe and Mail

In 1999, we learned to pay close attention to the men behind the curtain. For two decades, producer Garth Drabinsky and his finance-whiz sidekick, Myron Gottlieb, had dazzled both theatregoers and investors. Drabinsky was the loud one, always braying about the next big success. Gottlieb was quiet, happy to tug financial levers in the shadows. They started together in movies, financing the surprise 1978 hit The Changeling, then launching the Cineplex chain. Drabinsky had vision, turning Cineplex into the fastest-growing exhibition company on the continent. Gottlieb had sway with the financial backers who could help make it happen. When one of those, the media conglomerate MCA, got tired of the pair’s overspending in the late 1980s and pushed them out, Drabinsky and Gottlieb turned to live entertainment. The concept gave them the eventual company name: Livent Inc.

Torontonians, blustered Drabinsky, have “an insatiable demand for drama that has not been satisfied over the last 20 years.” The two men acquired control of significant theatres—buying the Imperial Six Theatre on Yonge Street and restoring it to its former Pantages glory; gaining management control of the North York Performing Arts Centre before it was even built; block-booking Toronto’s grand Elgin-Winter Garden Theatre for months. Then Livent filled them with long-running productions of, among others, The Phantom of the Opera and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. It financed Kiss of the Spider Woman and took it to Broadway, winning the Tony for Best Musical in 1993. Costly productions of Showboat and Ragtime followed.

But as Drabinsky and Gottlieb tooled about in chauffeured cars, Livent hemorrhaged money. Eventually auditors pulled back the curtain and found books cooked to the tune of $500 million. By 1999, Livent was bankrupt. Then came a decade of legal proceedings, both civil and criminal, until the two men were each convicted of fraud and forgery. Sentenced initially to six (Gottlieb) and seven (Drabinsky) years, their time was reduced on appeal. In 2011, they entered a minimum-security federal prison and, two and three years later, respectively, they were out on full parole. No applause could be heard.

– Trevor Cole

Hollowing out

Gord Nixon

Gord Nixon, former president and CEO of RBC in September 2002.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

In September 1999, the organization representing the country’s top CEOs sent an urgent memo to Prime Minister Jean Chrétien calling for radical action as more and more domestic companies were gobbled up by foreign rivals. The missive from what’s now known as the Business Council of Canada pointed the finger at a weak currency, high corporate and personal taxes and restrictive regulations, and it was the opening salvo in a debate that would consume this country during the first decade of the 21st century as one iconic business after another disappeared. Shareholders in MacMillan Bloedel, Imasco, Newcourt Capital, Labatt, Seagram, Newbridge Networks and others had sold out to foreign bidders, while some domestic-based giants that had expanded abroad, such as Nortel, were largely being run from outside Canada.

The trend had accelerated in the years following the 1988 Canada-U.S. free-trade agreement, but its root causes went far deeper than open borders. No factor seemed to contribute more to the fire sale than our declining currency. When the BCC issued its clarion call, the loonie was hovering around 67 cents (U.S.), down from 90 cents earlier in the decade. In early 2002, the dollar hit a record low of 61.79.

In May of that year, RBC CEO Gordon Nixon noted in a wave-making speech that no fewer than 62 of Canada’s largest companies, representing 27% of the public float on the TSX 300 index, had disappeared since 2000. More than half had been bought by foreigners. “Foreign investment is important, and open markets are critical, but we should be asking why so many of our industry leaders are being consolidated rather than doing the consolidating; why we are losing head offices at such an alarming rate; and what is the cost,” Nixon warned.

Nixon’s speech sparked plenty of talk on Bay St. but not much action in Ottawa. The sell-off continued as legendary companies such as Inco, Falconbridge, Dofasco, Alcan, Hudson’s Bay Co. and Viterra were, within a few years, all swallowed by foreign bidders.

At the turn of the decade, a new kind of predator was prowling corporate Canada: state-owned enterprises, mainly but not exclusively from China. The Canadian dollar had by then hit parity with the greenback, but that couldn’t deter deep-pocketed SOEs from setting their sights on Canadian resource assets. Ironically, the Harper Conservatives limited SOEs to minority stakes in domestic resource producers, though after it approved the takeovers of Nexen by China’s CNOOC and Progress Energy by Malaysia’s Petronas.

Before long, “hollowing out” gave way to the “Canadianization” of the oil patch. One by one, foreign-based multinationals began reducing or selling their holdings in Alberta’s oil sands, in part because of the negative publicity associated with its higher-carbon crude. Domestic players like Suncor, Canadian Natural Resources and Cenovus scooped up the assets that foreign companies shed.

Indeed, foreign control of the Canadian economy has been declining for a decade. In 2020, it stood at 15.1% of total assets, or $2.2 trillion of the $14.8 trillion in total assets, according to Statistics Canada. That was down from 19.2% in 2010. Even so, Canada has fallen farther behind the rest of the developed world on productivity and innovation. And our currency is on the wane again, in spite of aggressive rate hikes by the Bank of Canada as it seeks to quash inflation. Plus ça change…

– Konrad Yakabuski

Convicted newspaper baron Conrad Black leaves the federal building in Chicago on Dec. 10, 2007, after sentencing in his racketeering and fraud trial.Jerry Lai/The Associated Press

Fall of a newspaper empire

Conrad Black

It seems quaint now, the idea of building a newspaper empire. And given that Hollinger International reached its peak as the Internet Age dawned, it was arguably a little quaint at the time. Yet thanks to the combative, self-important Conrad Black, who never smiled if he could sneer, it usually entertained, in the going up and the coming down.

Black established his pattern early: acquire struggling properties and—with the help of close associates—slash costs. In the late ‘70s he maneuvered two widows into giving him control of Argus, a company partly owned by his deceased father, and shuffled control of the shares to another of his father’s holdings, Hollinger Mines. Buying small papers in big handfuls, Black created Sterling Newspapers and later transferred those properties to Hollinger. In 1985 he landed a prize—50.5% of the U.K.’s Telegraph. London society, he found, suited him, and he moved there in 1989. His marriage didn’t withstand the upheaval, and so Black (who for a time penned a column for this magazine) married the Canadian journalist and photographer magnet Barbara Amiel, who found Black’s growing wealth suited her: “My extravagance knows no bounds.”

By the mid-’90s, Hollinger International was the third-largest newspaper group in the world, with nearly 250 properties, including some of Canada’s Southam chain, most of The Jerusalem Post and all of The Chicago Sun-Times. It also had massive debt, which failed to quell Black’s ambitions. He craved a national newspaper in Canada, and when he couldn’t buy one (a bid for The Globe and Mail had failed), he launched The National Post in 1998.

The dream was short-lived. Sinking in debt, Hollinger sold most of its small newspapers and 50% of the Post to CanWest in 2000 for $2.1 billion, and added millions in non-compete payments, then unloaded the rest of the Post and its debt a year later for $1. Perhaps to salve his wounds, Black applied for a British peerage in 2001 and, when the Canadian government stood in his way, renounced his Canadian citizenship. He was made Baron Black of Crossharbour, a place that existed only as a station on a London light-rail line.

A few years later, U.S. authorities looked closer at those non-compete payments and other Hollinger finagling, and saw crimes. In 2004, the SEC filed civil fraud lawsuits against Black and his associates. In 2005, criminal charges came, for fraud, racketeering, money laundering and more. When Black tried to remove boxes of documents from his office, a charge of obstruction was added. In 2007, he was convicted of fraud and obstruction, and sentenced to six and a half years in a Florida prison. He was released in 2012 and immediately shipped back to Canada by U.S. officials. Novelist Gore Vidal told a Globe writer that he found the whole saga of Lord and Lady Black rather delicious: “The pure treachery with which they did everything was kind of admirable. They were pure!”

– TC

Oil sands boom

Jim Davidson & Murray Edwards

Jim Davidson, chairman of FirstEnergy Capital Corp.ALEX RAMADAN/The Globe and Mail

Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. chairman Murray Edwards in May 2019.Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

When small and mid-size oil and gas producers became market darlings in the mid-1990s, Jim Davidson saw the opportunity to establish a Calgary-based boutique energy dealer to help them raise money for an upcoming drilling and takeover bonanza. Along with Rick Grafton, Brett Wilson and Murray Edwards, he set up FirstEnergy Capital to take advantage (along with Peters & Co., GMP Capital, Yorkton Securities and Tristone Capital) of the wave of acquisitions, freewheeling spending and rush of deals at the hands of income trusts.

As oil prices surged, deep-pocketed competitors rushed in to do business with domestic producers like Canadian Natural Resources, Encana and Talisman Energy. Big Canadian banks beefed up their Calgary energy franchises. U.S. and European financial institutions opened branch offices. The corporate world shifted, too: Imperial Oil Ltd., long a fixture of the Toronto business scene, moved its headquarters out west in 2004. Soon, energy accounted for 30% of the S&P/TSX composite index, neck and neck with financial services.

Now, after the end of the income trust boom, years of weak oil and gas prices, pipeline delays, then a shift in market sentiment to more climate-friendly investment, oil and gas is a distant second on the index at 17 per cent. Energy companies tap the market for capital far less, and several small dealers have shut their doors in Calgary. For its part, FirstEnergy has been sold to rivals twice in the past seven years. For Davidson, that does not diminish what he and his colleagues accomplished.

As Davidson says: “We identified the vacuum, and we understood why it was created. The outcome...was a combination of good people identifying an opportunity and then working their asses off.”

– Jeffrey Jones

Chef Mark McEwan at Bymark Restaurant.Supplied

Yes, Chef

Mark McEwan

He might hail from Buffalo, N.Y., but no other chef defined the bro-centric, skinny-suit Bay Street culture of the early aughts like Mark McEwan, who opened Bymark at the foot of the TD towers in 2002, not long after the dot-com bust decimated dealmakers. Bankers went to the tucked-away, starkly masculine “it” spot to drown their sorrows in shots of Rémy and $33 burgers topped with melted brie, porcinis and black truffle. As deals picked up again, so did the booze-fuelled backslapping—and, COVID-19 notwithstanding, it hasn’t really stopped since, making Bymark a Bay Street institution.

The magazine’s June 2006 issue featured Bay Street's Mike Wekerle.BrianA/The Globe and Mail

Trading god

Mike Wekerle

Mike Wekerle rose to fame on the Street as head trader at the legendary First Marathon—founded by trading legend Lawrence Bloomberg—then jumped to Griffiths McBurney and Partners (GMP), where one of his key deals was the 1997 Research In Motion IPO. As Sinclair Stewart wrote in “Live fast and prosper” (June 2006): “Everyone has a theory as to how Wekerle pulls it off. Is it his indefatigability, his refusal, at 42, to burn out? His contacts? His memory? His math power?

‘You saw the movie Amadeus?’ asks Seymour Schulich, the wealthy investor and philanthropist. ‘To me, he’s the character in that movie, Mozart. He’s a prodigy. I’ve never seen a guy who can keep more deals in his head than that guy. I’m not even close. He must have somewhere between 25 and 50 deals in his head at any given time. He’s the best I know.’

Oh, and one other thing, Schulich adds: ‘He’s got the balls of a cat burglar.’”

Wek left GMP in 2011 and, in addition to his personal hijinks, is best known to the new generation for spending 12 seasons slaying entrepreneurs on Dragons’ Den.

Hottest central banker

Mark Carney

Mark Carney at the Bank of England's headquarters in London, in December 2019.Francesca Jones/The Globe and Mail

Mark Carney was once asked by a waggish reporter what it was like being the George Clooney of central banking. “It’s a very low bar,” Carney shot back.

He’s right. But with a winning smile and a closet full of well-tailored suits, the former Goldman Sachs investment banker brought more than a hint of glamour to the stodgy business of managing the currency. In 2003, he left high finance for the (slightly less) glittering lights of Ottawa, working first as a deputy governor at the Bank of Canada before moving to the Department of Finance.

In a world of career bureaucrats, the Wall Street hotshot stood out. He became an advisor to successive finance ministers. And in 2008, he became, at age 42, the second-youngest governor in the Bank of Canada’s history. Carney quickly found himself piloting the economy through a full-blown financial crisis. He slashed the benchmark interest rate and promised to keep borrowing costs at rock-bottom for an extended period—a novel technique copied by other central banks.

Canada weathered the crisis better than its peers, winning Carney plaudits and fame. It also brought suitors. In 2012, the British chancellor of the exchequer wooed Carney away from the Bank of Canada to lead the Bank of England, which economist David Rosenberg likened to Wayne Gretzky being traded from Edmonton to L.A.

After seven years across the pond, Carney is back in Ottawa, working as the head of impact investing at Brookfield Asset Management, and stoking perennial rumours that he has his eye on one final adornment to his resumé: prime minister.

– Mark Rendell

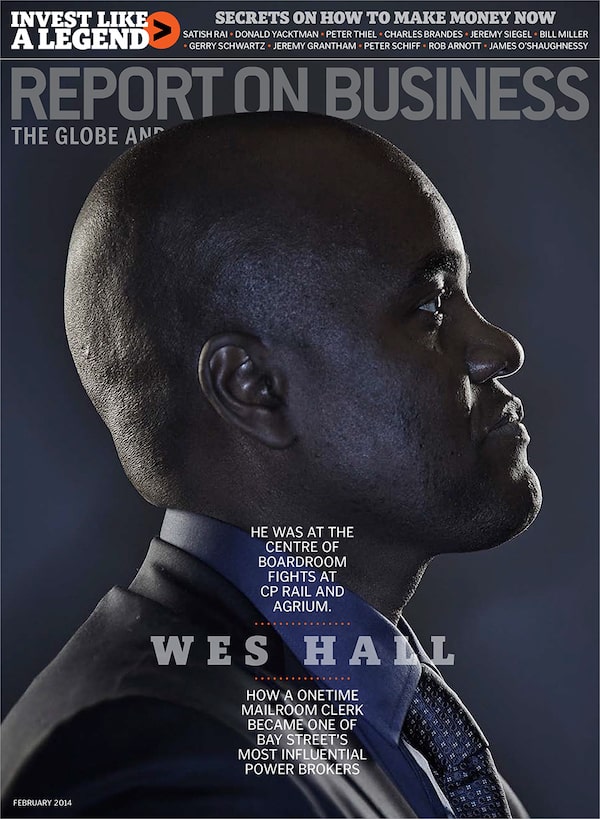

Wes Hall on the cover of the February 2014 issue of the REport on Business magazine.Liam Sharp/The Globe and Mail

Shareholder activism

Wes Hall

A consummate outsider who grew up, as he’s fond of recounting, in a tin shack in Jamaica, Hall became the face of the full-combat world of activist investing circa 2011, when he helped New York hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman change the regime at CP Rail. “In Canada, if you’re an activist investor leading a shareholder uprising, or you’re the CEO (or board) under siege, you usually either hire Hall or end up staring at him on the other side of the table,” wrote Doug Steiner in “The fixer” (February 2014). Hall went on to create the BlackNorth Initiative, whose mission is to end systemic anti-Black racism.

Global financial crisis

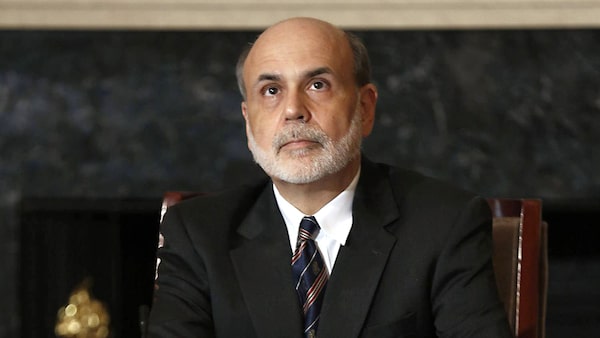

Ben Bernanke

Amid a marathon meeting of the U.S. Federal Reserve in December 2008, chairman Ben Bernanke made a confession: “Even I do not know all the acronyms anymore.”

The economist, who had been educated at Harvard, taught at Princeton and worked for the White House, had spent the previous year leading the Fed’s response to the real estate crash and subsequent financial crisis. Despite his intellectual prowess, even Bernanke couldn’t quite keep straight all the credit facilities and “non-traditional” policies making headlines on a daily basis.

And fair enough. At the time, the only way to fight a crisis heralded by three-letter acronyms (CDO and CDS) seemed to be with four-letter ones (TARP).

The causes of the 2007-2009 financial crisis, or Great Recession, or Global Financial Crisis (GFC, as some on the internet insist on calling it), were simple. Encouraged by low interest rates and loosening regulations, banks granted risky mortgages. Those loans were bundled together and turned into financial assets. Shaky securities built from wobbly mortgages became an unsound foundation for the financial sector. When homeowners began defaulting on their loans, it wiped out Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and nearly $8 trillion in value on the U.S. markets.

Ben Bernanke, former Chair of the US Federal Reserve.LARRY DOWNING/The Globe and Mail

The underlying causes of the crisis are straightforward, but keeping up with the details required learning a new vocabulary. There was the collateralized debt obligation (CDO), the catchall name for the financial products often built from iffy mortgages. Those CDOs came in a bewildering number of variations, from mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to asset-backed securities (ABS) to collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). And one needed to know the difference between a CDO and a CDS, or credit default swap, a derivative often used to offset credit risk. Banks thought using a CDS would mitigate the dangers of a CDO, but their overuse contributed to the GFC. Americans uttered a collective OMG, which led to the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), a US$440-billion bailout of banks and other firms.

Confusion was possible even when acronyms weren’t being flagrantly deployed. The risky loans to homeowners were known as “subprime” mortgages, which suggested a relationship to the prime interest rate, but instead indicated that their recipients had less-than-ideal credit histories.

The banks and hedge funds may have deployed acronyms and buzzwords to appear clever. As the narrator of The Big Short, a 2015 movie about the crisis says: “Wall Street uses confusing terms to make you think only they can do what they do. Or, even better, for you to just leave them the f–k alone.” Or the arcane language worked to obscure risk. “It was hard to take in the fact that CDSs were on the verge of bringing down the entire global financial system when you’d never even heard of them until about two minutes before,” wrote John Lancaster in The New Yorker. Either way, the public seemed capable of determining what really mattered. The most frequently searched word on the Merriam-Webster website in 2008 was “bailout.” People might not have followed exactly what happened. But they definitely knew what it cost them.

– James Cowan

Bharat Masrani, Group President and CEO of TD Bank Group in September 2020.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Busting barriers

Bharat Masrani

Not many Bay Streeters knew Bharat Masrani’s name before he became TD Bank’s new CEO—the first non-white man to rise to the position at one of Canada’s big banks. In his October 2014 cover story, Tim Kiladze wrote: “TD...is betting that the man who blew Ed Clark away can win over Bay Street too—just give him enough time.” TD is neck and neck with RBC among Canada’s Big Five banks ranked by assets, and that has required resolute stickhandling. Masrani cut jobs in 2014 and 2015, bought Wall Street’s Cowen Inc. in 2022 and walked away from a US$13.4-billion deal to buy Memphis-based First Horizon Corp. earlier this year.

Tobias Lütke, founder and CEO of Shopify, in October 2015.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The enigma

Tobias Lütke

Every so often, investors get overly excited about a fast-growing company, driving the total value of its outstanding shares to, well, if not the moon, then at least past perennial top dog RBC and the top of the S&P/TSX Composite Index. Shopify—led by German savant Tobias Lütke, who was our CEO of the Year in 2014, six months before the company’s explosive IPO—made it to the top in 2020 and stayed there for a year. It then plummeted by more than 80% over 11 months.

Shopify is hardly the first company to fall prey to the RBC curse. Nortel, Barrick Gold, Potash Corp. (now Nutrien), Research In Motion (now BlackBerry) and Valeant Pharmaceuticals (now Bausch Health) all briefly held the mantle as Canada’s most valuable company before sinking—sometimes disastrously—below RBC. To Lütke’s credit, Shopify remains among the top handful of companies by market cap on the TSX. And the man himself remains a rare character in the modern-day corporate realm.

As Trevor Cole wrote in his 2014 profile: “Lütke relates to software the way a musician relates to the music he plays. ...Programming comes so easily to him, ‘it’s almost meditative.’ It’s easy to see how someone so inclined could become a brilliant software engineer. But start a company? ‘I think I probably had to start a company,’ he admits, ‘because I don’t think I can work for other people.’”

Cannabis craze

Bruce Linton, founder and CEO of Canopy Growth Corporation, in March 2019.Rémi Thériault/The Globe and Mail

Bruce Linton

The day recreational cannabis was legalized—Oct. 17, 2018—was the beginning of the end. Until then, producers’ sky-high valuations were unassailable. Deloitte suggested the recreational market could be worth as much as $5 billion a year, to start, as startups with little more than a growing licence were ushered onto the stock market by investment banks like Canaccord and GMP, which reaped millions in fees. Canopy Growth, led by the irrepressible Bruce Linton, quickly became Canada’s largest producer, with a sky-high market valuation and a $5-billion investment from giant Constellation Brands.

But as soon as Canadians could legally buy pot, the bubble started leaking, and then it burst. Producers had grown way more than they could sell, while longtime users stayed loyal to their cheaper dealers. Producers grumbled about stringent and costly regulations but hyped the legalization of edibles and beverages in 2019, while looking to pump CBD into every product imaginable. Stock prices soon tumbled, layoffs ensued, assets were sold. Canopy’s share price peaked two days before legalization in 2018 and has fallen 99% since then.

– Joe Castaldo

Looking west along King St. West, from Yonge St, the streets of Toronto are quiet amid the early onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, devoid of the workers who make up city life.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The end of the world as we know it

COVID-19 pandemic

When an as-yet-unnamed coronavirus sent all but the most essential workers into lockdown in March 2020, the conventional wisdom was that we’d all be toiling back in our office-tower cubicles in a few weeks at most.

We were so innocent then! After more than two years of intermittent lockdowns, the world has irrevocably changed—and so has Bay Street, which has lost much of the bustle (but somehow none of the traffic) of its pre-pandemic days. Nearly 16% of commercial office space in Toronto currently sits empty, and much of modern-day financial history is being written from basements and kitchen tables. Which means Bay Street is slowly becoming more a state of mind than an actual place.