A crane stands over a construction site in Vancouver on Sept. 30, 2020.JENNIFER GAUTHIER/Reuters

When Naz Ali was sitting at home in March, under lockdown along with the rest of Vancouver, she had the idea of using her specialized skills to track data on people’s movements owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ms. Ali is a geographic information systems (GIS) manager, location intelligence, for commercial real estate services company CBRE Canada. Her work tracking traffic – as well as other data such as demographics – helps developers, retailers and other clients determine the best locations for their investments.

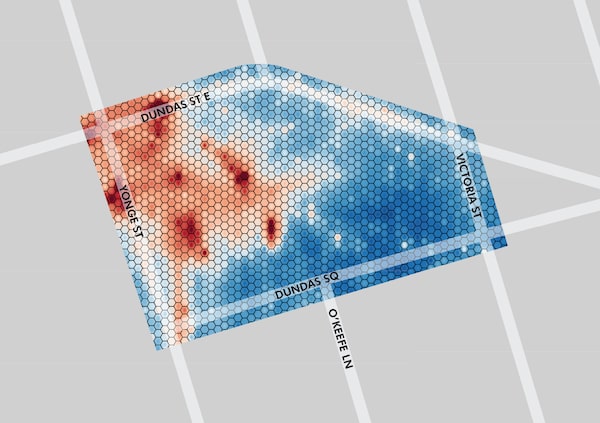

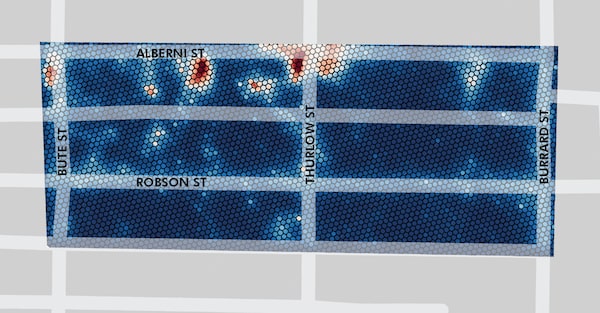

She created a heat map comparing foot traffic in the downtowns of three of Canada’s largest cities before and after the lockdown. A stark picture emerged from her analysis of the data, using third-party mobile-device tracking data from Yonge-Dundas Square in Toronto, Robson Street in Vancouver and Sainte-Catherine Street in Montreal between January 1 and May 31, 2020.

Compared with 2019 patterns, the red in the heat maps rapidly cooled to blue. Foot traffic in Vancouver decreased by 74 per cent, by 84 per cent in Toronto and by 88 per cent in Montreal.

Toronto's Yonge-Dundas Square in early 2019, above, and the first months of the lockdown in 2020.

Vancouver's Robson Stree in early 2019, above, and the first months of the lockdown in 2020.

Areas outside downtown cores have also been affected by lockdowns, and building owners and managers, business and retail tenants and investors and developers are not only looking to respond in the short term but are looking at what trends may continue long term.

“Everything right now is shaped by COVID,” says Carl Gomez, chief economist and head of market analytics Canada for commercial real-estate data provider CoStar Group Inc.

“Changes in the way we are doing things – whether it’s online shopping or working from home – have had a material impact on a number of industries.”

As a result, the hardest-hit segments in the industry have been office and retail.

“We will likely see a snapback in growth in 2021 into 2022, but even at that point … behaviours have changed, scarring has occurred and the new normal … is going to be different,” Mr. Gomez says.

REITs and headwinds

As people look for signs of what will happen in the commercial real estate industry, one indicator is the performance of real estate investment trusts (REITs).

“There has been a recovery in the public equity markets … but one sector that has lagged is the REIT sector,” Mr. Gomez says.

“Retail REITs have really taken it on the chin, and the office REITs as well. … I think what is happening is that investors are looking at future earnings in that space and discounting it heavily because of the perceived changes that they’re seeing.”

Another indicator is sublease vacancies.

“I think the only reason we haven’t seen vacancy rates rise higher … is the long lease rates companies have,” says John Andrew, a professor and director of Queen’s University’s Executive Seminars on Corporate and Investment Real Estate.

But as businesses see their office space sitting empty, some are starting to put up space for sublease, which is a leading indicator for demand, Mr. Gomez says.

On the other hand, many of the institutional investors, such as pension funds, have a much longer-term outlook.

“These longer horizons from pension funds – they’ve got a lot of capital behind them, they can ride out short-term storms,” Mr. Gomez says.

Empty offices

A lot of office space is owned by institutional investors, Prof. Andrew says. Especially the highest-quality Class A buildings, which are typically occupied by blue-chip companies.

“There always will still be some tenants who will value having office space, but they are going to value the newest, the best, type of office space out there with great HVACs, great flexibility in terms of amenities,” he says. The real estate arms of pension funds have the capital to develop the most desirable properties as the number of potential tenants interested in large chunks of office space in downtown locations may shrink, he adds.

“Some of the smaller office owners are probably going to be in trouble,” Prof. Andrew says. “Falling prices … asset values could decline significantly … rent levels could fall.” Class B and C buildings may be hit harder, he says.

In the meantime, building owners and managers have had to keep near-empty buildings running, says Benjamin Shinewald, president and chief executive officer of the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) Canada.

“The big question is the whole return to work … what is that going to look like?” Prof. Andrew says.

“I think the future [of office space] is hybrid,” Mr. Shinewald says. Health considerations will likely mean businesses will need more space per employee, but fewer employees will likely be in offices on a daily basis, he adds.

Regional differences

Experts note a few regional differences.

Toronto and Vancouver had the tightest vacancy rates, Mr. Gomez says, and are most likely to have the room to adjust to a post-COVID situation. “I don’t think they will see a significant rent [reduction].”

“Calgary is an extreme example of what can go wrong,” he adds. The pandemic exacerbated a city already hit by a drop in oil prices.

A sluggish Montreal market had taken off in the past couple of years, especially from a growth in the tech sector and financial fields. But, he adds, suburban office supply in the region may not bounce back.

One longer-term trend in higher-density cities globally is the high rents in downtown offices. Combined with the movement of millennials, especially, to living in the suburbs, this may boost suburban office markets, Mr. Gomez says.

Retail and repurposing

Because of the rise of e-commerce, “retail was in trouble before COVID,” Prof. Andrew says.

This trend has affected not only malls but street-level retail because of empty office buildings, Mr. Shinewald says.

Some developers with long horizons are looking at redeveloping sites to multiuse spaces, including residential, retail and service, creating a live-work space. This is a trend predating COVID, especially where there is public transit to support it, Mr. Gomez says.

Some retail space may be repurposed to distribution centres, which are increasingly needed as more people buy online, Mr. Gomez says. This may especially be the fate of smaller businesses in small-bay industrial spaces, such as manufacturers or dance studios. These are often in prime locations near large populations and can work as locations for “last mile” distribution needs.

Landlords in some street-level retail locations may look for short-term leases, such as pop-up stores, Mr. Gomez suggests.

As for Ms. Ali, she is hoping to do another study combining demographic data with the mobility data from devices to show trends related to continuing COVID effects on commercial real estate.

“The pandemic gave me an opportunity to look at data in a different way.”