Brampton, Ont., is home to some of the country's most financially distressed neighbourhoods.Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

Navin Seepaul is a 29-year-old single dad who makes $30,000 a year as a barber. He owns a $1-million house in Brampton, a sprawling suburb northwest of Toronto. Each month, the payments on his roughly $700,000 mortgage are $4,300. On top of that, he has $24,000 in credit card debt.

“The more you work, the more you spend,” says Mr. Seepaul. “‘What is $1,500? What is $2,000? Let me just run this credit card here.’ A lot of people do it.”

To help pay the bills – even just the monthly interest charges are staggering – he rents out his basement to three or four students, and two truck drivers rent bedrooms on his second floor. At any given time, the young father has six vehicles parked on his property.

Welcome to the Canadian suburbs, circa 2019, where the country’s debt problem is at its worst, and where the dream of owning a home on a leafy street with a garage and a lush yard for the kids is, for many, a long way from reality.

Thanks to soaring real estate prices – driven to extremes through a combination of constrained supply, low interest rates and eager lenders – Canada’s total household debt has hit a record $2.2-trillion. Canadian households are carrying debt equal to 177 per cent of annual disposable income.

But there’s another number that should be more concerning: the debt service ratio. That’s the percentage of after-tax income households must spend to pay the interest on their debts – not just the mortgage, but also car loans, credit cards and lines of credit.

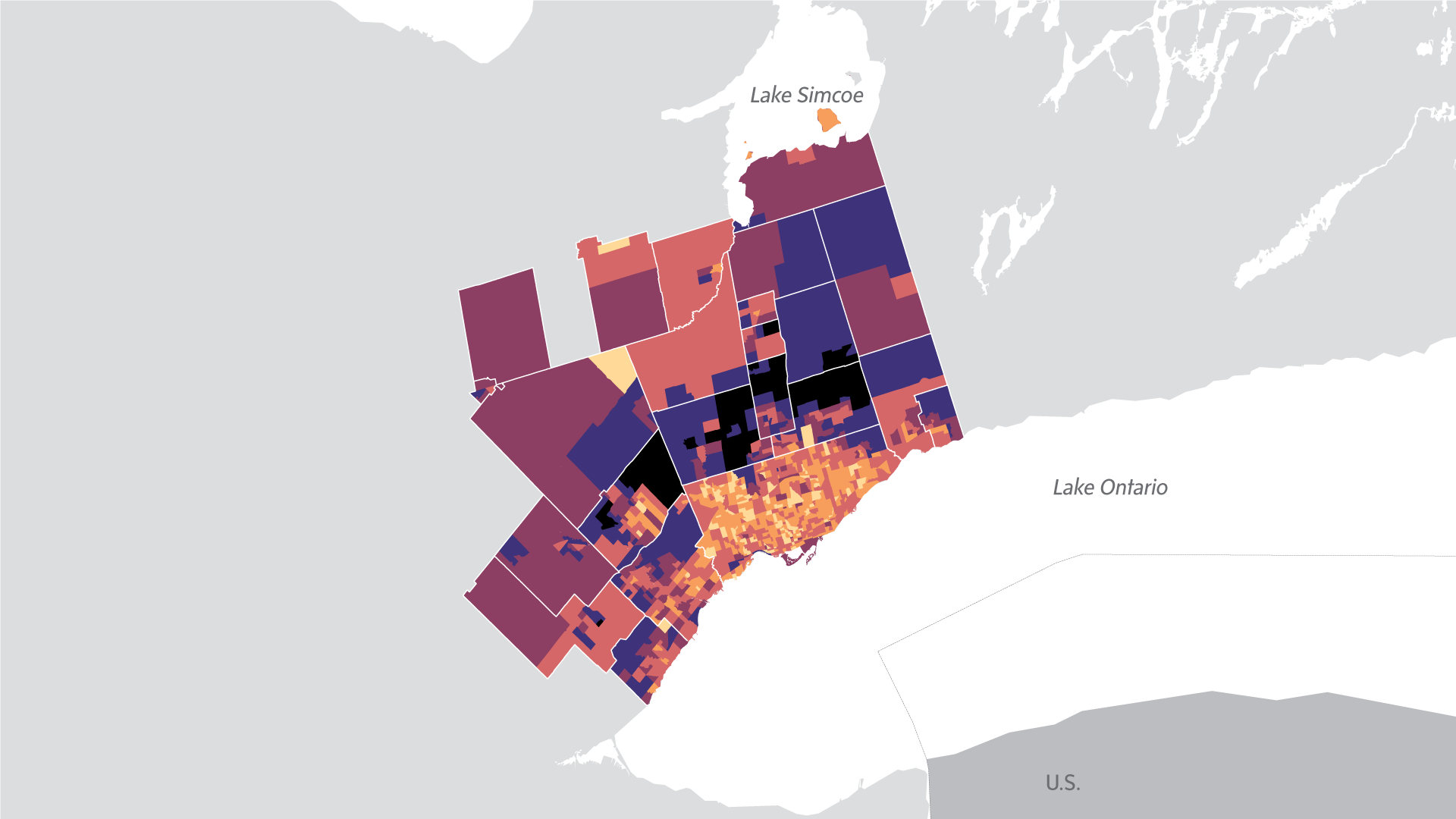

The Globe and Mail asked Environics Analytics to pinpoint the 100 most financially stressed neighbourhoods in the country – census tracts with the highest debt service ratio. Nationwide, it sits at 8.4 per cent, according to Environics (which calculated the figure using data from Statistics Canada, the 2016 census, Equifax and the Bank of Canada, among other sources).

But in the 100 most maxed-out neighbourhoods, homeowners are spending more than 16 per cent of their after-tax income on interest, and an average of 22 per cent.

Housing affordability has long been considered an issue in the core of the biggest cities, with prospective buyers in Toronto and Vancouver bemoaning the fact that it now costs well over $1-million to buy a detached house. The suburbs used to be the haven of affordability for families. That’s no longer the case.

Canada’s most financially stressed neighbourhoods are almost exclusively in the suburbs, Environics’ analysis shows.

CANADA’S DEBT HOT SPOTS

Percentage of take-home income spent

on interest payments

6

8

10

12

16%

VANCOUVER CMA*

Vancouver

0

25

U.S.

KM

CALGARY CMA

Calgary

0

75

KM

EDMONTON CMA

Edmonton

0

100

KM

TORONTO CMA

Lake

Ontario

Toronto

0

50

KM

*CENSUS METROPOLITAN AREA

CANADA’S DEBT HOT SPOTS

Percentage of take-home income spent

on interest payments

6

8

10

12

16%

VANCOUVER CMA*

Vancouver

0

25

U.S.

KM

CALGARY CMA

Calgary

0

75

KM

EDMONTON CMA

Edmonton

0

100

KM

TORONTO CMA

Lake

Ontario

Toronto

0

50

KM

*CENSUS METROPOLITAN AREA

CANADA’S DEBT HOT SPOTS

Percentage of take-home income spent on interest payments

6

8

10

12

16%

VANCOUVER CMA*

CALGARY CMA

Vancouver

Calgary

0

25

0

75

U.S.

KM

KM

EDMONTON CMA

TORONTO CMA

Edmonton

Toronto

0

100

0

50

KM

KM

*CENSUS METROPOLITAN AREA

CANADA’S DEBT HOT SPOTS

Percentage of take-home income spent on interest payments

6

8

10

12

16%

VANCOUVER CMA*

CALGARY CMA

Vancouver

Calgary

0

25

0

75

U.S.

KM

KM

EDMONTON CMA

TORONTO CMA

Edmonton

Toronto

0

100

0

50

KM

KM

*CENSUS METROPOLITAN AREA

CANADA’S DEBT HOT SPOTS

Percentage of take-home income spent on interest payments

6

8

10

12

16%

VANCOUVER CMA*

CALGARY CMA

EDMONTON CMA

TORONTO CMA

Vancouver

Calgary

Edmonton

Toronto

0

25

0

75

0

100

0

50

U.S.

KM

KM

KM

KM

*CENSUS METROPOLITAN AREA

Fifteen are on the fringes of Vancouver – places like Langley, Surrey, Coquitlam and Richmond. Two are in Calgary’s northern outskirts, and four are in Edmonton, clustered south of the highway that rings the city. (Just two are in a city’s downtown core: one in Montreal and one in Vancouver.)

The rest? Look to the Greater Toronto Area.

Canada's debt hot spots

Percentage of take-home income spent on interest payments- 6

- 8

- 10

- 12

- 16%

Canada's debt hot spots

Percentage of take-home income spent on interest payments- 6

- 8

- 10

- 12

- 16%

Canada's debt hot spots

Percentage of take-home income spent on interest payments- 6

- 8

- 10

- 12

- 16%

Canada's debt hot spots

Percentage of take-home income spent on interest payments- 6

- 8

- 10

- 12

- 16%

After a decade of cheap money, the GTA is swimming in debt. Seventy-seven of the most debt-ridden neighbourhoods are found in the Toronto area.

Located on the region’s outskirts, these neighbourhoods tend to be younger, have more occupants per household, and their residents are more likely to be born outside Canada.

Thirty-four are in Brampton. Another 43 are in cities surrounding Toronto: 21 in Vaughan, 11 in Markham, five in Richmond Hill, four in Whitchurch-Stouffville, one in Milton and one in Aurora.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/H6MEEWVHC5BLNDMLXWTUITP4NQ)

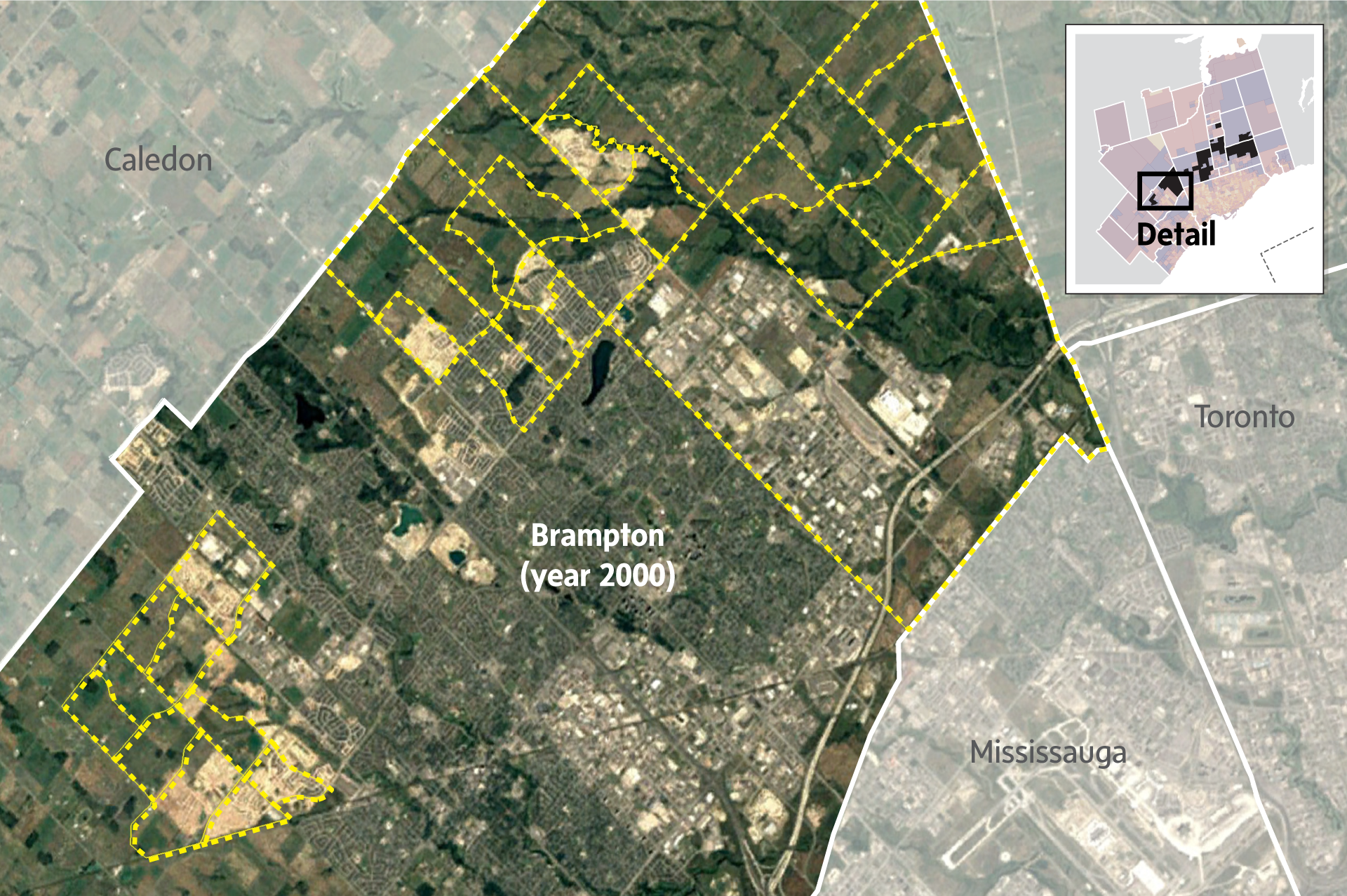

Decades ago, Brampton was a farming town. But like many places across the country, its population has exploded as families seek affordable housing within commuting distance of urban centres.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/VMHUCCZHBZAIDGTC4EIWSJIV54.jpg)

Today, Canada’s debt-laden neighbourhoods tend to be in subdivisions built in the past two decades, and where real-estate prices have sky-rocketed.

There’s long been talk that Canada is due for a debt reckoning, and insolvencies and mortgage defaults are already on the rise. If an economic slowdown is really on the way, these over-extended neighbourhoods could become the first casualties.

With financial anxiety at such high levels, political parties are responding. In one of his first campaign announcements this week, Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau promised a foreign-buyers tax on vacant homes, and an enhanced first-time home buyers program – all designed to address the affordability crisis for middle-class Canadians. Meantime, Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer talks of tax cuts as a “plan to put more money in your pocket so you can get ahead.” The New Democrats’ “New Deal for People” vows to tackle “the suffocating pressure that people feel as costs keep tightening the family budget.”

The ’burbs, after all, contain a healthy number of ridings key to winning the federal election in October.

If there is a debt crisis in Canada, Mr. Seepaul is living at its epicentre.

Brampton, a.k.a. Flower City, was once a farming town known for its many greenhouses. But as Toronto grew as a financial hub, so did Brampton, sprouting rows of detached houses connected by roads as wide as six lanes. It became a hub for immigrants, many from South Asia, and a place where Sikh temples are common and strip malls are packed with Indian grocers.

Today, Brampton epitomizes the suburban debt-stress phenomenon by pretty much every measure. Its population has increased twice as fast as Toronto’s over the past decade, to nearly 600,000, making it the fourth-biggest city in Ontario, after Toronto, Ottawa and Mississauga.

All that growth has translated into an insatiable demand for homes. Forty-three per cent of Brampton’s housing was built between 2001 and 2016, compared with 26 per cent across the Toronto area. As rising house prices in Toronto sent people rushing to the suburbs, prices jumped in Brampton. The average selling price for a detached house in the city has tripled over the past decade, from $312,918 to $908,354. In Toronto, meanwhile, the cost of a detached home rose from $522,200 to $1.36-million.

It’s making Brampton unaffordable, says Jas Takhar, a realtor whose work spans the Toronto region, including Brampton: “We have a saying in my office. It’s ‘Drive till you qualify.’ So you can’t buy in Toronto, you can’t buy in Brampton, you have to go to Hamilton, you have to go to Kitchener, you have to go to Durham.”

It’s telling that nearly 80 per cent of homeowners in Brampton have a mortgage, compared with 63 per cent in the Toronto region as a whole, making the area more vulnerable to interest rate changes. And the pressure built up when the Bank of Canada began hiking its key lending rate two years ago, from 0.5 per cent to 1.75 per cent. When you add in the principal to interest on loans, Canadians are now spending a record 14.9 per cent of their disposable income on debt repayments, according to StatsCan. Environics calculates Canadian households spent an additional $663 on interest payments in 2018, compared to the previous year.

The high cost of the suburbs extends beyond simple house prices, however. The median monthly shelter cost for homeowners – which includes mortgage payments, property taxes, heat, water, electricity and other municipal services (but not house insurance) – was $1,897 in Brampton, $1,827 in Vaughan and $1,814 in Richmond Hill, according to the most recent census data. That compared to $1,655 in the Toronto census metropolitan area.

Among the 34 Brampton neighbourhoods identified by Environics, the median monthly shelter cost for homeowners was nearly 30 per cent higher, at $2,132, according to the Globe’s analysis of Environics and census data.

MEDIAN MONTHLY SHELTER COST FOR

HOMEOWNERS IN INDEBTED NEIGHBOUR-

HOODS IN THE GTA

Each bar represents one of the

77 GTA neighbourhoods

$2,600

2,400

2,200

2,000

Brampton Average

1,800

Toronto Average

1,600

1,400

1,200

1,000

800

600

400

200

0

Rest of GTA

Brampton

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS, ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

MEDIAN MONTHLY SHELTER COST FOR

HOMEOWNERS IN INDEBTED NEIGHBOURHOODS

IN THE GTA

Each bar represents one of the 77 GTA neighbourhoods

$2,600

2,400

2,200

2,000

Brampton Average

1,800

Toronto Average

1,600

1,400

1,200

1,000

800

600

400

200

0

Rest of GTA

Brampton

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS, ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

MEDIAN MONTHLY SHELTER COST FOR HOMEOWNERS

IN INDEBTED NEIGHBOURHOODS IN THE GTA

Each bar represents one of the 77 GTA neighbourhoods

$2,600

2,400

2,200

2,000

Brampton Average

1,800

Toronto Average

1,600

1,400

1,200

1,000

800

600

400

200

0

Rest of GTA

Brampton

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS, ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

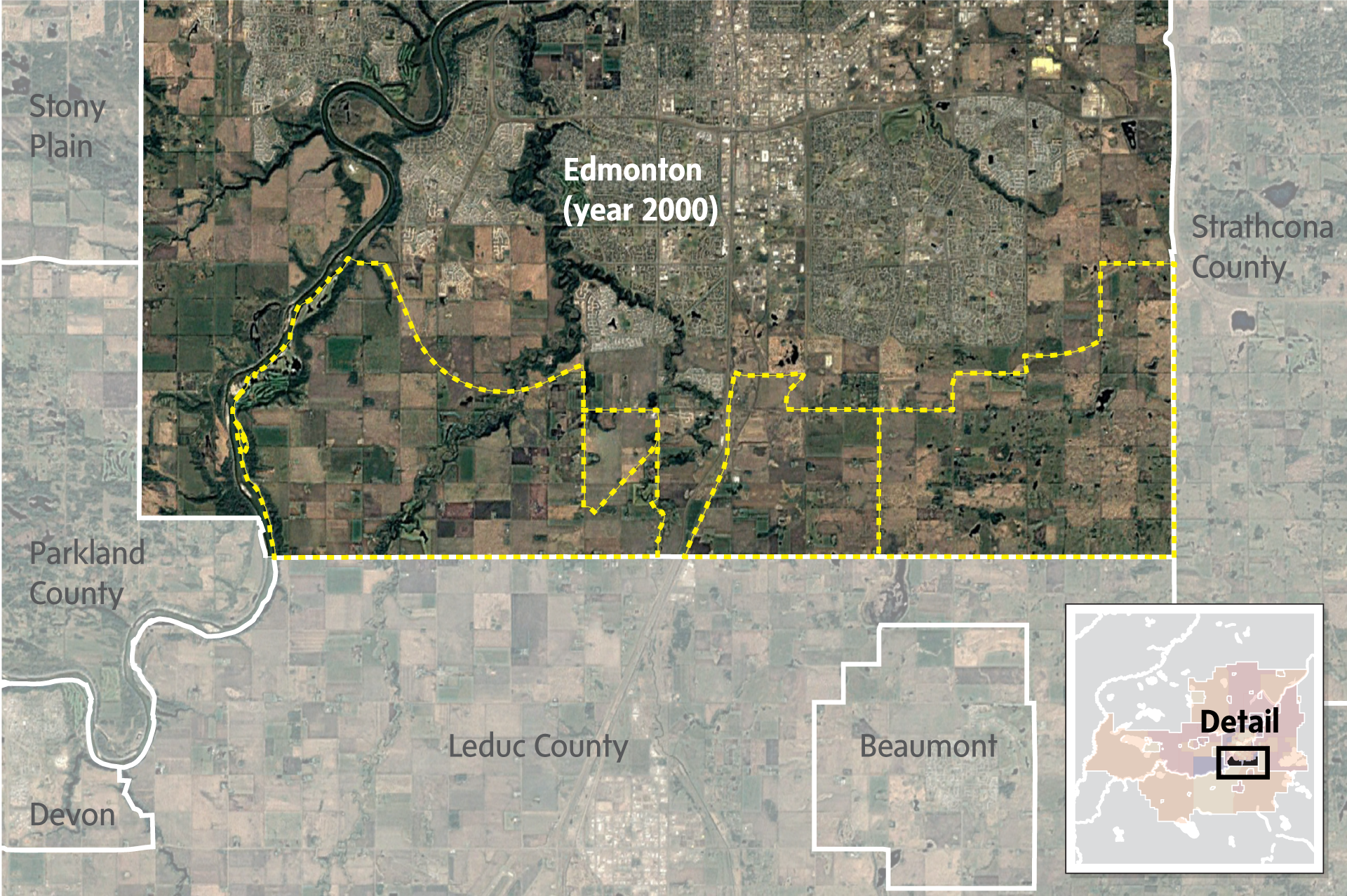

It’s the same story in other suburban areas. In the two distressed neighbourhoods in Coquitlam, the median monthly shelter cost was $1,895 – 38 per cent higher than the Vancouver area’s median of $1,376. In the four census tracts on the outskirts of Edmonton, housing costs were $2,012, versus $1,536 in the city’s census metropolitan area.

Even property taxes can be surprisingly burdensome. Since many bedroom communities have a limited corporate tax base, residential property taxes constitute the bulk of municipal revenue. In Brampton, 80 per cent of its property tax revenue comes from residents, versus 20 from commercial buildings like offices. In contrast, Toronto’s property tax revenue is 53 per cent residential and 47 per cent commercial.

“We don’t have the same level of corporate taxes. That may make it the perfect storm: high property taxes, higher interest rates, high car insurance,” say Harkirat Singh, a Brampton city councillor who represents the northeast area with neighbourhoods with the highest debt service ratio. “They call it postal code discrimination.”

The high cost of commuting is another killer. About two-thirds of Brampton’s work force drives out of the city for employment. It’s the same in other 905 areas like Markham, Richmond Hill and Vaughan. In Richmond and Surrey, B.C., it’s about half; in Coquitlam, the figure climbs to 75 per cent.

SUBURBAN COMMUTERS

IN GREATER TORONTO

Percentage of workers who commute

out of their municipality

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90%

Lake

Simcoe

U.S.

Lake

Ontario

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS

SUBURBAN COMMUTERS IN GREATER TORONTO

Percentage of workers who commute

out of their municipality

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90%

Lake

Simcoe

U.S.

Lake

Ontario

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS

SUBURBAN COMMUTERS IN GREATER TORONTO

Percentage of workers who commute out of their municipality

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90%

Lake

Simcoe

U.S.

Lake

Ontario

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS

Owning a car is a pricey proposition – and not just because of loan payments, gas and maintenance. Brampton, Vaughan and Richmond Hill have, on average, the highest car insurance rates in the country at $2,600 per year, due to a higher number of claims. B.C. has the second highest rates with an average of $1,800 per year.

“When you have a lot more financial pressures like we do now, people are forced to make tougher choices,” says Peter Miron, an economist and senior researcher with Environics. "How much am I saving if I sit in traffic in the car? I think everyone is well aware of that cost.”

Meanwhile, even as expenses have risen in the suburbs, wages haven’t. Part of the problem in Brampton, and in plenty of other suburbs, is that the majority of local jobs are on the lower end of the income spectrum. In Flower City, half the labour force is employed in manufacturing, wholesale trade, retail, transportation, food services and accommodation, and the median employment income was $31,399 in 2015, nearly $3,500 less than in Toronto.

To Benjamin Tal, deputy chief economist with CIBC, that suggests something’s askew. “The fact that the debt-to-income ratio is rising very rapidly, or the stress is higher there, suggests that income is not as high as it should be to support home prices."

“It’s not a question of how much debt you have,” Mr. Miron says. “It’s more a question of, how much debt do you have relative to your income?”

Across the country in Edmonton, Stacy Lee and her partner, Peter Halladay, are struggling with the income side of the debt-service equation. In 2015, they paid $415,000 for a 1,500-square-foot detached house, complete with white-railinged porch, in a new subdivision called Chappelle. The family moved there from a small community south of Edmonton because Ms. Lee wanted to raise their two children, now 8 and 6, in a culturally diverse neighbourhood close to a school.

Stacy Lee at home with her kids Victoria Halladay, 8, and Piers Halladay, 6, in Edmonton in July. Ms. Lee and her husband lost work and hours during the oil downturn and are constantly trying to pay down their debt.Amber Bracken/The Globe and Mail

So far, that future is still under construction. Excavators and big piles of dirt dot the subdivision, and front yards are filled with mud, not grass. The school is nothing but an open field. Nonetheless, her subdivision is part of one of the city’s fastest growing neighbourhoods, below the highway that surrounds the city.

It’s also one of the four Edmonton-area neighbourhoods on the list of Canada’s most financially stressed areas.

The Great Recession, followed by the oil crash, have taken their toll on the region. Ms. Lee, 38, has lost four jobs in sales and management since 2011. Mr. Halladay, 48, a quality control inspector at a wellhead manufacturer, has had his hours cut three times since the 2008 meltdown.

Ms. Lee says she has been able to fully pay off their credit cards, lines of credit and other consumer debt four times, only to accumulate more. “There is a never-ending trail of recovery and indebtedness,” she says.

Recently, she landed a full-time job with Canada Post and started paying down their credit cards yet again. But when the transmission on her 14-year-old car failed, she had to buy a new one. “We just keep slipping back,” she says. “Something will happen with his truck, or the kids got to go to camp, or school supplies are due.”

With credit card payments and car loans of $1,188 a month, along with the monthly mortgage of $2,225, the couple’s total debt payments will reach $40,956 this year. Of that, $14,000 is interest. Add in childcare, groceries, gas and other expenses, and Ms. Lee expects to spend more than $82,000 this year – far outstripping their expected after-tax pay of $74,760.

“We are probably less than a paycheque away from being in trouble,” says Ms. Lee, who is looking for a second job – any job – to bridge the gap. “I am $1,000 in the hole every month just to pay the bills, not to pay any debt.”

The Lee-Halladays aren’t alone. “What’s driving [the higher debt-service ratio] is still people not having the same level of income,” says Freida Richer, an insolvency trustee with Grant Thornton in Edmonton. “They were able to afford it when they had the income they had, but they no longer have that income.”

So far, the country’s economy is humming along, and the jobless rate is at a four-decade low. The Bank of Canada has kept interest rates steady this year, giving some homeowners a reprieve.

But the record level of debt makes the economy less resilient.

“The real test is when interest rates rise or when you have an economic shock like an increase in the unemployment rate – that is when you feel the pain,” CIBC’s Mr. Tal says. “Clearly, a higher level of debt is making the economy more sensitive to economic shocks, no question about it.”

There are some early signs of stress. In Edmonton’s southern suburb, insolvencies are rising, according to the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions. In the first eight months of the year, foreclosure sales in the western city hit 385, according to Coldwell Banker, a real estate brokerage that specializes in foreclosures, putting it on track to outpace last year’s figure.

The uptick in insolvencies and delinquencies isn’t isolated to Edmonton. In the first quarter of this year, Ontario and B.C. showed their first “significant” rise in consumer debt delinquencies in five years, according to Equifax. “There is evidence that the delinquency trend is gaining upward momentum,” says Bill Johnston, Equifax’s vice-president of data and analytics. “We continue to see signs of increasing strain for Canadian borrowers.”

Worried about household debt, the nation’s bank regulator is forcing the big banks to hold more capital to guard against potential loan losses. At the same time, the banks are becoming increasingly stringent about loans, making it harder for customers to refinance and consolidate their debts. Others are seeing interest rates on their lines of credit or credit cards increase with no explanation.

“I can’t go to my bank now and shift my Visa balance onto my line of credit,” says Scott Terrio, manager of consumer insolvency for Hoyes, Michalos Licensed Insolvency Trustees in Ontario. “That is a big deal. It doesn’t sound like much. But that’s what people were doing for the last five years.”

When people start running out of options, that’s when you’ve got trouble coming, according to Mr. Terrio, adding that insolvencies in Ontario are increasing at a pace not seen since 2009. “When those doors start to close," he says, “I think the next insolvency peak will blow 2009 away.”

Even more worrisome is what will happen if a recession hits – a distinct possibility, given the brewing trade war between the U.S. and China. For people like Ms. Lee, losing a job could mean missing debt payments, which could lead to insolvency and foreclosure. More houses on the market would depress price and weaken the housing industry, triggering further job losses.

“It will make the recession deeper and longer,” says mortgage broker Rob McLister, founder of Ratespy.com.

Those in debt-stressed neighbourhoods, however, don’t need a recession to put them at risk. Any unexpected expense – a broken-down car, a leaky roof, a sudden illness – can put them over the edge.

“People are living with a very, very narrow margin," Mr. Tal says.

About 30 kilometres east of downtown Vancouver is a perfect illustration of how the debt crisis is reshaping the suburbs.

The neighbourhood, known as Burke Mountain or northeast Coquitlam – one of Environics’ most stressed areas – is filled with freshly built rows of single-family homes, built on the last piece of land north of the Fraser River still available for housing. Young families rushed to buy in, paying upwards of $1-million for detached houses, many of them with a basement suite ready to rent out. “That was their way of getting into the market,” says Craig Hodge, a Coquitlam city councillor.

“Densification,” in which parking lots, strip malls and low-rise buildings are turned into condos and apartments to jam in more people, is a well known phenomenon in downtown Toronto and Vancouver. Now it’s accelerating in the suburbs, many of which are facing limits on sprawl.

In Coquitlam, the city is providing developers with incentives to turn low-density spaces into multiresidential properties. “Single-family detached is not selling that much anymore because of the cost,” says Brent Asmundson, a city councillor with Coquitlam.

Today, 98 per cent of the housing under construction in Coquitlam is townhouses, duplexes, apartments or condos. Basement apartments or secondary units are becoming more common.

“If someone has the choice of, I can either buy a $2-million single family house or I can get a unit in a four-plex for $800,000, that is open to a wider range of families,” says Andrew Merrill, Coquitlam’s manager of community planning.

In Brampton, the city is approving more building permits for apartments, and it’s also pushing for more density around the three train stations that lead to downtown Toronto.

Brampton City Councillor Harkirat Singh meets with a group of seniors in Ward 10 in Brampton, Ont., on Aug. 28, 2019.Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

It is also coming to terms with the spike in renters and unsanctioned rental spaces. In 2015, it passed legislation requiring residents to obtain permits to lease their basement apartments or secondary units. The number of issued permits soared from 67 in 2015 to 1,263 last year. From January to May, the number hit 811, putting it on track to outpace the previous year.

Mr. Singh, the Brampton city councillor, says he is getting calls from constituents asking for more bus routes. “I know the people in the houses, and I am like, why public busing? I know these people – they are not going to take public busing," he says. “But it is to make it more attractive for people in the basement apartments.”

Among the financially stressed neighbourhoods in Brampton, an analysis by StatsCan suggests that more households were renting a part of their house in 2016 compared with 2011. The average number of people per household in those neighbourhoods is 4.2 people, compared with 3.5 across Brampton and 2.7 for the Toronto region, according to a Globe analysis of the data.

AVERAGE HOUSEHOLD SIZE OF THE

INDEBTED NEIGHBOURHOODS IN THE GTA

Each bar represents one of the

77 GTA neighbourhoods

5

4

Brampton Average

3

Toronto Average

2

1

0

Rest of GTA

Brampton

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS, ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

AVERAGE HOUSEHOLD SIZE OF THE

INDEBTED NEIGHBOURHOODS IN THE GTA

Each bar represents one of the 77 GTA neighbourhoods

5

4

Brampton Average

3

Toronto Average

2

1

0

Rest of GTA

Brampton

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS, ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

AVERAGE HOUSEHOLD SIZE OF THE INDEBTED

NEIGHBOURHOODS IN THE GTA

Each bar represents one of the 77 GTA neighbourhoods

5

4

Brampton Average

3

Toronto Average

2

1

0

Rest of GTA

Brampton

SOURCE: 2016 CENSUS, ENVIRONICS ANALYTICS

As in Coquitlam, Brampton planners and developers are pushing densification. “That accelerated with all sorts of financial pressures,” says Brampton’s city planner, Bob Bjerke. “If you think of suburbs being low-rise houses with parks, where everyone drives to everything – no, I don’t think that is going to be the predominant way people live.”

A few years ago, Brampton consulted with about 15,000 residents on the municipality’s future. After four decades of ad hoc urban planning and momentous growth, city officials were looking for a different approach. The result was a vision for a future that included more jobs in the city, mini town centres throughout, and more public transit while still sustaining access to parks.

“In the future, we can’t just see core cities and second-tier cities" like Brampton, says Larry Beasley, a former chief planner for Vancouver who helped Brampton develop the vision for the city. “This community has to change.”

When asked if residents wanted to live in an apartment or townhouse instead of a detached house, Mr. Bjerke is confident they do: “There is an interest in what you can afford.”

But 75 years of suburban living will be hard to change with condos and public transportation, and some don’t want to give up, even in the face of spiralling debt.

When Brampton homeowner Sandy Brar went to renew her mortgage earlier this year, her monthly mortgage payment jumped from $1,600 to $2,400. “When I look at property taxes, when I look at the price of insurance for a car and my home , I would be saving money by moving out of Brampton,” she says.

Now, Ms. Brar and her family are looking to sell their house in Brampton and find something more manageable. She’s looking further afield – Milton, Oakville, maybe Burlington – in the hopes of holding on to the suburban dream.

Credits: Matt Lundy, digital editing; Murat Yükselir, graphics; Christopher Manza, web design and development

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.