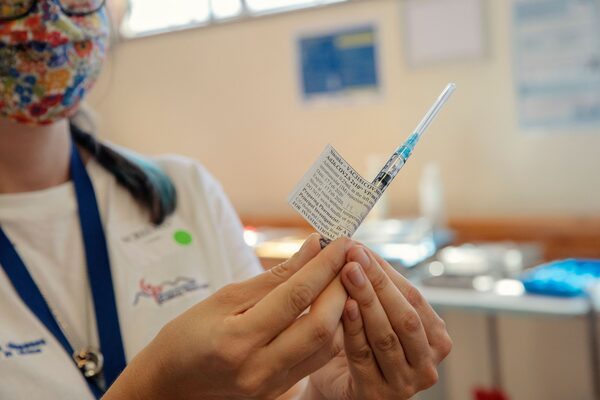

A South African health worker holds a dose of COVID-19 vaccine at the Khayelitsha Hospital, in Cape Town, on Feb. 17, 2021.GIANLUIGI GUERCIA/AFP/Getty Images

Vaccinating the world is beginning to take on the dimensions of a global Marshall Plan, the enormous U.S.-led effort to rebuild Western Europe after the Second World War. Yet it is failing. There are simply not enough vaccine doses to go around – the rich countries are keeping most of them.

The hoarding was inevitable. The U.S. and European Big Pharma companies developed the first approved COVID-19 vaccines in the West, and governments sped up the effort by handing them billions to fund trials and expand manufacturing and distribution. Exporting vaccines en masse would have triggered political mayhem.

The rich countries won easily. Canada has ordered almost 10 doses per person while about 130 other countries, most of them poor, have yet to administer a single jab. The massive disparity is unsustainable, immoral and unhealthy. As the World Health Organization keeps saying, no one is safe from the pandemic unless everyone is safe.

How to fix this injustice?

The first option isn’t working – or not working fast enough. The WHO-led COVAX shared-procurement program, whose goal is to provide vaccines to the 2.5 billion people in middle- and low-income countries, has been underfunded and has yet to deliver a single dose. The first trickle of deliveries should arrive at the end of February.

While COVAX deliveries will accelerate over time – U.S. President Joe Biden this week pledged US$4-billion for the program – it could take several years for full coverage in the developing world, assuming rich countries do not raid the program (as Canada shamefully has done). Delaying vaccination allows the virus to mutate into more contagious and lethal variants. That’s why South Africa and a few other countries are in a panic. The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine bought by South Africa has proven largely ineffective against mild and moderate South African variants, and the country is scrambling to find replacements.

As the body count rises in countries with few or no vaccines, another option would see the compulsory licensing of vaccine technology. In this scenario, countries would insist that the World Trade Organization (WTO) suspend intellectual property rights on COVID-19 vaccines and related therapeutic treatments. Big Pharma would lose its monopoly rights until the pandemic is gone, allowing manufacturers anywhere to make the vaccines in exchange for royalty payments.

So far, South Africa, India and other developing countries have called for the suspension of IP rights. The idea is supported by 100 governments and civil society groups. But resistance is fierce. The United States, Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, Australia and Brazil, among others, insist that strict IP protection – read: fat profit margin assurances – is the best way to guarantee vaccine innovation and supplies. They smell a heist.

The proponents of compulsory licensing are deluding themselves in one sense, but not in another.

Compulsory licensing would not magically trigger a flood of supplies. Making vaccines is complicated and capital intensive, and most of the countries in dire need of vaccines have little or no production capacity at the moment.

Technology transfers would be required. Factories and distribution networks would have to be built, employees trained, certifications obtained. The new-generation mRNA vaccines, like the ones developed by Pfizer and Moderna, would be particularly expensive to distribute because they require extremely cold storage. Bottlenecks would form. The effort could take a year or two in developing countries, and those with scant medical infrastructure might have no ability to start their own production.

Still, the governments backing compulsory licensing are onto something and should keep up the pressure. “Compulsory licensing is like playing chicken,” said Pierre Morgon of MRGN Advisors, a Swiss-based biotech and vaccine consultancy. “It’s a game and it’s a credible threat because Big Pharma is afraid of the consequences if they just say no. They might be forced to negotiate.”

South Africa pursued compulsory licensing during the HIV/AIDs crisis in 1997, when it was trying to get access to inexpensive antiretroviral drugs. Big Pharma went ballistic and sued the government for breach of IP rights. The suit triggered mass demonstrations, with protesters and charities such as Oxfam alleging that the shortage of treatments was costing lives. The U.S. and the EU backed off, and South Africa was able to secure the treatments at lower prices.

Threatening compulsory licensing could embarrass Big Pharma into cutting a deal with developing countries to boost supplies, reduce prices or build manufacturing capacity in afflicted regions. Last month, when the EU vaccine rollout was in shambles, European Council President Charles Michel threatened the industry with a patent raid to try to boost vaccine supplies. The threat seems to be vanishing as the EU signs new supply agreements, though it may have expedited those new contracts.

This week, French President Emmanuel Macron, evidently judging the IP suspension threat to be credible, urged Europe and the U.S. to send as much as 5 per cent of their vaccine supplies to developing countries.

South Africa and other countries short of vaccines should keep their compulsory licensing threat alive. It has worked before. It is immoral for rich countries to hoard most of the supplies. This is a global health crisis. Failure to share the vaccines will only prolong it.

Sign up for the Coronavirus Update newsletter to read the day’s essential coronavirus news, features and explainers written by Globe reporters and editors.