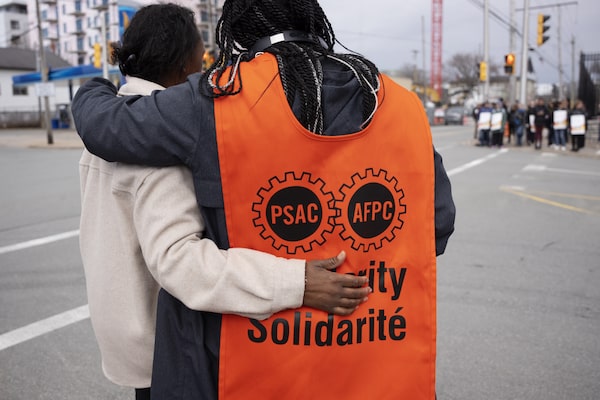

PSAC workers and supporters walk a picket line in Halifax on April 19.Darren Calabrese/The Canadian Press

Michael Wernick is the Jarislowsky Chair in public sector management at University of Ottawa and the former clerk of the Privy Council.

During the current labour dispute Canadians will hear from the public-service unions and from the employer’s negotiator, the Treasury Board. There are only two ways the story can end. One is a negotiated settlement ratified by the union membership. The other is back-to-work legislation that imposes terms or sends issues off to binding arbitration. There is a strong incentive for both sides to find a landing zone for an agreement, but it may take time and test the patience of the broader public.

Hidden in plain sight are thousands of supervisors, managers and executives across the country. They too are public servants. They too were affected by the surge in inflation. They too have families and households that depend on them. They too need raises.

Managers are often the subject of snarky tropes. However, their importance deserves more respect and attention. Managers play a vital role in determining whether public-sector organizations are productive by setting priorities and tasks, exercising quality control and interacting with other teams. They are the conduit between the most senior leadership and the rank and file. They are key to setting organizational culture and values and determining whether work environments are inclusive and healthy. They perform essential roles in providing performance feedback and identifying talent for investments in training and future promotion. For many of them the acceleration of hybrid work arrangements has brought new challenges and called on new skill sets. Their jobs can be demanding and a strain on resilience and well being.

The pattern in the past has been to shunt the concerns of managers and executives to the side during collective bargaining rounds and to pass on an economic increase long after the unions have settled. The specific concerns of executives only get attention periodically.

More than 155,000 federal government workers are on strike. These services will be affected

I think we can do better this time. I would like to see Treasury Board president Mona Fortier commit in advance that at the end of this round of bargaining with the unions, she will immediately put in place a fair economic increase for executives. But she should go further. She should sit down with the Association of Professional Executives of the Public Service and hammer out terms of reference for a thorough review of the executive group’s issues – which include the approach to total compensation; the approach to pay at risk; the structure of the executive group (how many levels); and issues of salary inversion between executives and the professionals they often supervise. The methodology for classifying executive jobs needs updating for the work world of the 2020s.

She should restore the external Advisory Committee on Senior Level Retention and Compensation, which existed from 1997 to 2015, and stock it with leading edge expertise familiar with the private and not-for-profit sectors and the changing nature of work.

I would like to see a commitment from all political parties to invest in the capacity of the public service and to at least double the annual investment in training and leadership development.

One of my regrets from my time as clerk of the Privy Council is that I failed to draw more attention to these issues. At the time the pay system and the previous collective bargaining round created an environment where the Treasury Board president chose not to open up another set of issues, as was his prerogative. It is 2023 and again attention is on the collective bargaining process. Public-service managers should be given their day, too.