St. Michael's Hospital in 2015, the year that Bondfield Construction Co. Ltd. won a contract to manage a major redevelopment there.Kevin Van Paassen/The Globe and Mail

More than 10,000 pages of recently unsealed court documents show that dealings between a senior Toronto hospital executive and a construction company chief executive officer were far more extensive than reported so far, and the pair went to great lengths to conceal them.

Vas Georgiou was chief administrative officer of St. Michael’s Hospital from 2013 to 2015, and John Aquino was CEO of Bondfield Construction Co. Ltd. when it won the coveted contract to create Canada’s premier critical-care centre in 2015 – a $300-million project that is mired in protracted delays.

The unsealed documents were filed by Zurich Insurance Co. Ltd., which issued surety bonds on the project. The multinational insurer alleges Mr. Georgiou received kickbacks, including free home renovations, and “secretly obtained” shares, worth at least $500,000, in companies owned by Mr. Aquino.

Details of the alleged kickbacks – contained in e-mails and transcripts – were barred from public view. But the records were released in March after The Globe and Mail successfully fought a judge’s order that sealed them.

Zurich alleges the unsealed evidence shows:

• Mr. Georgiou funnelled confidential information to Bondfield throughout the bidding process.

• Mr. Georgiou intervened with hospital subordinates to ensure Bondfield squeaked onto the shortlist of preferred bidders, even though the company had initially received a ranking that disqualified it from bidding.

• Even after Mr. Georgiou was fired by St. Michael’s in 2015, he continued to use his influence to help Bondfield. In a 2017 e-mail, he urged Mr. Aquino to “get something” for Michael Mendonca, the hospital’s vice-president of the redevelopment, and who was recruited to the hospital by Mr. Georgiou.

The alleged kickbacks were discovered by Zurich after it launched a lawsuit last year against Mr. Georgiou, Mr. Aquino and Unity Health Toronto – the hospital network that includes St. Michael’s – arguing the two men orchestrated a “bid-rigging scheme” to ensure Bondfield won the contract.

None of the allegations have been proved in court. Lawyers for Mr. Aquino and Mr. Georgiou said it would be inappropriate for them to comment while the matter is before the courts. Mr. Georgiou’s lawyer said her client denies any wrongdoing.

Vas Georgiou, top, and John Aquino, bottom.

Zurich is seeking a court order to rescind the surety bonds it issued. Those bonds are insurance-like contracts that were supposed to act as a safety net for the project, and required Zurich to foot the bill in the event Bondfield faltered.

And falter it did. Bondfield collapsed in 2019, fired Mr. Aquino as CEO and sought court protection from creditors. Zurich, which issued bonds for dozens of Bondfield’s public infrastructure contracts across the province, was forced to insert itself into the company’s affairs.

Once installed at Bondfield’s headquarters north of Toronto, Zurich found evidence that Mr. Aquino and Mr. Georgiou had been improperly exchanging information throughout the St. Michael’s bidding process. Mr. Aquino had provided Mr. Georgiou with a secret BlackBerry and even his own bondfield.com e-mail address, which they used to pass messages.

Zurich also discovered that when The Globe began publishing stories in September, 2015, about the close ties between the two men, Mr. Aquino ordered his IT staff to wipe all references to Mr. Georgiou from the company’s e-mail server. The mass deletion of those estimated 5,000 e-mails, however, did not capture every mention of Mr. Georgiou. Zurich found scores of internal Bondfield documents – with notations such as “owe Vas $500,000” – allegedly showing Mr. Georgiou received multiple benefits from Bondfield before, during and after the St. Michael’s procurement.

Zurich argues that the alleged collusion should nullify any obligation it has to pay for the completion of the project. If the insurance giant is successful, it raises questions about who will ultimately pay for the redevelopment, which is 3½ years behind schedule and has left the hospital with an unfinished project in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The records Zurich has pried out of Bondfield’s computer servers also call into question the efforts – or lack thereof – of Infrastructure Ontario, the province’s procurement arm, to unravel the relationship between the two men.

Globe stories in 2015 and 2016 about Mr. Georgiou and Mr. Aquino detailed how they were involved in multiple businesses together, including a commercial real estate company and a bottled water venture, when Mr. Georgiou was supposed to be acting as a neutral evaluator of bidders.

In response to the revelations, the hospital and Infrastructure Ontario each hired teams of lawyers and forensic investigators, neither of which found evidence of the alleged kickbacks. A special committee of the board of Infrastructure Ontario went so far as to conclude that the “St. Michael’s Hospital procurement was not compromised.”

Bondfield, meanwhile, launched a $125-million libel lawsuit against The Globe. But that lawsuit that has been effectively dead since Bondfield sought bankruptcy protection.

Now, a recently established investigative agency of police officers and prosecutors, Ontario’s Serious Fraud Office, has launched a sweeping probe into Mr. Aquino, Mr. Georgiou and the procurement. Both Infrastructure Ontario and Unity Health Toronto, the network of hospitals that includes St. Michael’s, said in separate statements that they are co-operating with the police.

On March 19, The Globe successfully argued to Ontario Superior Court Justice Cory Gilmore that the records uncovered by Zurich should be released to the public. Mr. Aquino, Mr. Georgiou and Unity Health opposed the disclosure.

Mr. Georgiou denies he tipped the scales in favour of Bondfield. He was part of a steering committee of four senior officials who approved the shortlist of bidders, and another steering committee of four who ultimately recommended Bondfield win the contract – decisions by consensus that, he says, eliminated any outsized influence he may have tried to wield. “No one person … could materially influence or direct the outcome of the procurement process,” he has argued in court filings.

A pedestrian passes the St. Michael's Hospital emergency entrance this past fall. A Roman Catholic religious order founded the hospital on Bond Street in the 1890s.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

‘Vas is in!’

St. Michael’s Hospital, founded in 1892 with a mission of treating Toronto’s poor and vulnerable, long ago outgrew the space it occupies. A warren of crowded hallways with low-hanging ceilings, much of the facility belies the hospital’s world-class reputation for research and care.

By late 2012, the Ontario government had approved a major redevelopment, including a brand new 17-floor patient-care tower. Now, St. Michael’s just needed someone to manage the project.

The hospital believed it had just the man for the job – an executive with a background in health care and construction.

Vas Georgiou had been the chief administrative officer of Infrastructure Ontario, the agency responsible for all of the province’s major public-sector building projects, and before that, a senior executive at another Toronto hospital, St. Joseph’s Health Centre.

But a month before St. Michael’s even announced Mr. Georgiou’s appointment publicly in January, 2013, celebrations had begun in Bondfield’s head office.

On Dec. 18, 2012, Bondfield’s John Aquino, one of the company’s owners, received an e-mail from a colleague, “vas is in!”

Mr. Aquino and his company had many reasons to cheer the news. Bondfield, a mid-sized, family-owned construction company, was making a push to join the ranks of Ontario’s biggest players in public infrastructure. Winning the St. Michael’s contract would elevate the company into the big leagues with rivals EllisDon and PCL Construction.

And with Mr. Georgiou in a position of influence, Bondfield had a clear edge. Not only was Mr. Georgiou friends with Mr. Aquino, the two men were working together on multiple business ventures – a pair of commercial buildings in midtown Toronto, as well as a bottled water company, GP8 Sportwater. Neither disclosed these conflicts of interest in declarations they were required to fill out at the start of the St. Michael’s procurement.

But what few outside of Bondfield knew, until Zurich filed its materials in court, was that, over the years, Mr. Aquino had ordered his staff to perform many hours of free labour at Mr. Georgiou’s house in north Toronto. This included landscaping his yard, demolishing his driveway, carpentry inside his residence and working on his gazebo.

In April, 2012, about seven months before Mr. Georgiou started negotiations to join St. Michael’s, Mr. Aquino e-mailed one of his subordinates: “Call vas. We need to finish a few things at his place.” Other e-mails from 2013, 2014 and 2015 show Bondfield staff asked Mr. Aquino for instructions about how to record work done at “Vas house” or “Vas’s house.”

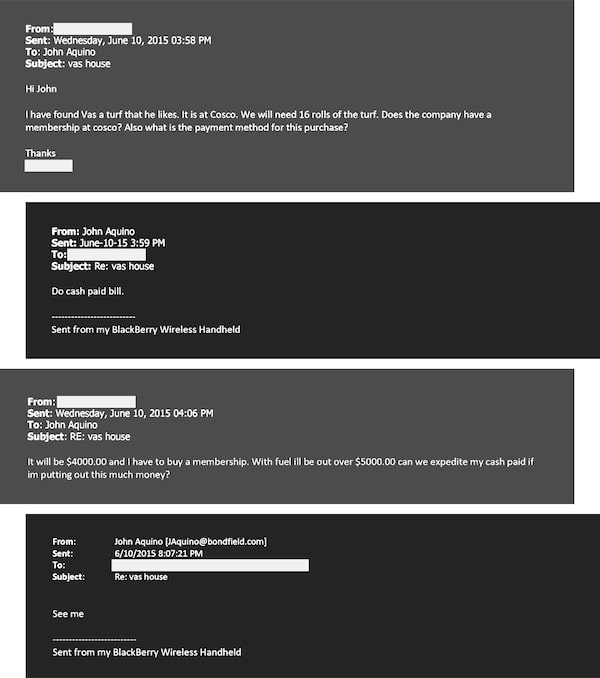

Another e-mail from June 10, 2015 – after the St. Michael’s contract was awarded to Bondfield – shows that a Bondfield landscaper wanted to know how he should pay for $4,000 worth of artificial turf Mr. Georgiou wanted for his backyard. A 2018 satellite image of Mr. Georgiou’s yard, examined by The Globe and taken at a time of year when everyone else’s lawn is drab and grey, shows a patch of bright green turf next to his pool and gazebo.

In the e-mail exchanges shown at top, a Bondfield staffer tells Mr. Aquino he has found turf for the backyard at Mr. Georgiou’s Toronto home, at bottom right in satellite view, with the house at street view at bottom left.Photos: Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail, Esri, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, i-cubed, USDA FSA, USGS, AEX, Getmapping, Aerogrid, IGN, IGP, swisstopo, and the GIS User Community

In 2020, Mr. Aquino was examined by lawyers for Zurich, and a transcript was part of the court filings unsealed at the request of The Globe. Under questioning by Zurich’s lawyer, Matthew Lerner, Mr. Aquino acknowledged Bondfield performed all of this work free of charge. “He didn’t pay because he was a friend and a client,” he said.

Mr. Aquino did not specify when the work began, but suggested it started while Mr. Georgiou was a senior executive at Infrastructure Ontario – the procurement agency that had awarded Bondfield several contracts, including multiple hospital projects and some of the facilities for the 2015 Pan American Games in Toronto. Mr. Georgiou worked at Infrastructure Ontario from 2006 until he was dismissed in 2012, after he was implicated in a false invoice scheme at Toronto’s York University.

“Is it fair to say you were doing this as a favour to him because of his role and influence at Infrastructure Ontario?” Mr. Lerner asked.

“Absolutely,” Mr. Aquino replied.

When Mr. Georgiou was examined under oath, his lawyers declined to allow him to answer any questions about the work Bondfield performed – with one exception. When he was asked about a 2013 e-mail from Mr. Aquino, which showed Bondfield replaced eight dead trees on Mr. Georgiou’s property, Mr. Georgiou replied, “I paid for those trees.” He explained that he paid Mr. Aquino in cash and sports tickets.

That same 2013 e-mail also raises questions about who was ultimately paying for the work on Mr. Georgiou’s home. In the e-mail, Mr. Aquino directed a Bondfield staffer to charge the work on Mr. Georgiou’s home to “Pick Go.” This is a reference to a parking garage Bondfield was building at the time at a Pickering, Ont., GO Transit station, Zurich alleges.

In an e-mailed statement, a spokesperson for Metrolinx, the provincial agency that oversees GO Transit, said it learned about this allocation because of The Globe’s inquiries. The agency is investigating these “troubling allegations,” said spokeswoman Anne Marie Aikins.

The Pickering parking garage contract was awarded on a lump-sum basis, and therefore, any extra costs should be born by Bondfield, not Metrolinx, Ms. Aikins said.

In his examination for discovery, Mr. Aquino refused, on the advice of his lawyers, to answer questions about his direction to record the costs to the GO parking garage.

For its part, Unity Health spokeswoman Sabrina Divell told The Globe that St. Michael’s had no knowledge at the time about the work done on Mr. Georgiou’s home.

John Aquino talks on the phone in his SUV last April outside Bondfield's office in Vaughan. Mr. Aquino was Bondfield's CEO when it won the St. Michael's contract in 2015.Cole Burston/The Globe and Mail

‘Owe Vas $500,000’

Other evidence uncovered by Zurich, the company alleges, shows that Mr. Aquino provided Mr. Georgiou with shares in businesses he owned.

In addition to running Bondfield, Mr. Aquino owned interests in numerous side ventures, including several residential housing developments and commercial buildings. Two of those buildings, on Gervais Drive in midtown Toronto, housed multiple commercial tenants. A spreadsheet of all of Mr. Aquino’s assets, found on Bondfield’s servers, included a notation next to the company that owned the buildings: “Owe Vas $500,000.”

Under questioning by Zurich’s lawyers, Mr. Aquino said he had “gifted” about $50,000 worth of shares in the company to Mr. Georgiou in 2012, before he was hired by St. Michael’s. Asked what Mr. Georgiou was supposed to do for the remaining $450,000, Mr. Aquino said he could earn it by giving him “assistance, advice, you know, like a – like a finder’s fee.”

Mr. Aquino said Mr. Georgiou didn’t do anything to earn the remaining $450,000, and he had no explanation for the spreadsheet that indicated he owed Mr. Georgiou $500,000. For his part, Mr. Georgiou denied, in his examination, having any interest whatsoever in the buildings. “I did not invest,” he said.

Zurich also alleges that other records show the two men were co-owners of another business – Potentia Solar Inc. Potentia, which landed a $1.2-billion contract in 2011 to outfit Toronto public schools with solar panels, was owned by people close to both men. (It has since been purchased by the Power Corp. family of companies and renamed Potentia Renewables).

In 2014 – in the middle of the St. Michael’s procurement – Bondfield’s then controller, Domenic Dipede, exchanged e-mails with another Potentia shareholder, Ted Manziaris, about Mr. Aquino and Mr. Georgiou investing.

Mr. Dipede wrote that Mr. Aquino was ready to invest, including “an additional $150k from Vas.”

“Please let me know whom the cheque should be made payable to and if it needs to be certified.”

When questioned by Zurich’s lawyers, Mr. Georgiou insists he didn’t invest. Mr. Aquino said that, when it came to Potentia, “Vas didn’t get a penny from me.” Mr. Aquino declined to answer any questions about why he didn’t disclose the two of them having ownership stakes before bidding on the St. Michael’s project.

Domenic Dipede, Bondfield controller at the time, corresponds with a Potentia shareholder about Mr. Aquino and Mr. Georgiou investing in the solar company.

In another e-mail, Mr. Aquino notes he is with Mr. Georgiou late one evening as a Bondfield employee prepares the company’s submission for the hospital project.

‘I am with Vas. We will be ok.’

After Mr. Georgiou joined the hospital, the first hurdle Bondfield had to clear was the Request for Qualifications, or RFQ.

That phase is designed to narrow the potential bidders down to a shortlist of the three top candidates. Five companies were vying for the contract: PCL, EllisDon, Bondfield, Turner Construction and Brookfield Multiplex.

E-mails recovered by Zurich show Mr. Aquino took comfort that Mr. Georgiou was in place for the RFQ.

On Jan. 29, 2013 – just a few weeks after Mr. Georgiou started his new job at the hospital – a Bondfield employee e-mailed Mr. Aquino to tell him he was working on the company’s submission.

Mr. Aquino replied, at 11:10 p.m., “Good. I am with Vas. We will be ok.” Asked by Zurich’s lawyers what he was doing with Mr. Georgiou so late at night, Mr. Aquino replied, “Maybe having a cigar.”

But when a team of evaluators first scored the bidders, they put Bondfield in fourth place – a ranking that, if allowed to stand, would eliminate the company from the race.

On March 19, 2013, those evaluators presented their scores to Mr. Georgiou’s steering committee, which was also made up of two officials from Infrastructure Ontario and a St. Michael’s official. But instead of accepting the scores, the steering committee sent the evaluators back to re-evaluate.

Two days later, they returned with new scores, and this time Bondfield had moved into third place, replacing Turner Construction, which had been knocked down to fourth.

Pressed to explain this by Zurich’s lawyers, Mr. Georgiou said Infrastructure Ontario had introduced new criteria that placed more emphasis on “local experience,” and the evaluators had not properly considered this in their initial scoring. Turner Construction has an office in Toronto, but is headquartered in New York.

Michael Keen, who is now vice-president of facilities at St. Michael’s, but at the time was one of the evaluators, was also questioned by Zurich’s lawyers. He said all four members of Mr. Georgiou’s committee directed his team to rescore the bidders.

Zurich, however, contends this was far more sinister. Mr. Georgiou “exploited his position … to influence the direction of the evaluation,” the company said in its pleadings.

If not for this change in scores, Bondfield “would not have been qualified.”

Three days before the deadline for bids, Mr. Georgiou advises Mr. Aquino to keep certain costs out of Bondfield’s proposed price.

‘We are low on St. Mikes’

As the deadline for the final bids crept closer, Mr. Aquino and Mr. Georgiou continued to exchange messages on the secret BlackBerry and Mr. Georgiou’s bondfield.com e-mail account.

On May 18, 2014 – three days before the deadline – Mr. Georgiou advised Mr. Aquino to keep certain costs out of Bondfield’s proposed price, explaining that he could “always fight later when we are No. 1.”

That was not the only e-mail in which Mr. Georgiou used the word “we” to describe Bondfield. Pressed to explain his choice of words by Zurich’s lawyers, Mr. Georgiou said that, in the event Bondfield did indeed win, the hospital would be “partners” with Mr. Aquino. “Using the word ‘we’ loosely did not infer that … I was on his team and I wanted him to win and not the others,” he said.

After the bids were submitted, the details of each were supposed to be confidential. Yet, on May 30, just nine days after submitting his bid, Mr. Aquino e-mailed his brother and father to let them know Bondfield had the lowest price: “We are low on St. Mikes.”

As for how that information filtered down to Mr. Aquino, Mr. Georgiou told Zurich’s lawyers he had no explanation. Only Infrastructure Ontario knew those figures, and even he hadn’t been told at that point, he said.

But sensitive and confidential bidding information continued to flow Mr. Aquino’s way.

On July 23, 2014, the evaluators tasked with reviewing the design submissions of the bidders presented their scores to the steering committee of four senior officials, including Mr. Georgiou. Again, the scores were not favourable to Bondfield. The company had just eked out a passing grade. The evaluators gave the company a design score of 70.74 per cent – only a hair above the 70-per-cent threshold for disqualification.

This barely satisfactory score was not good enough for one of the Infrastructure Ontario officials on the steering committee. Derrick Toigo, then a senior vice-president with Infrastructure Ontario, refused to approve Bondfield’s bid. Mr. Georgiou had a heated argument with Mr. Toigo, which one witness described as a “raised voice discussion.”

Mr. Toigo’s opposition had serious implications. Infrastructure Ontario’s rules required the steering committee to be unanimous and his concerns meant the procurement could fail.

PCL had received a glowing design score of 86.22 per cent, but the high price tag it proposed – $538-million – ruled the company out entirely. EllisDon’s design was considered non-compliant and it was disqualified. That left only Bondfield, which bid $299-million – 45-per-cent lower than PCL. (Because the hospital had added scope to the project as the bidding process progressed, it had taken the unusual step of letting bidders know its target price was about $301-million.) But without Mr. Toigo’s support, the contract couldn’t be awarded.

Sure enough, the day after Mr. Georgiou’s argument with Mr. Toigo, Mr. Aquino wrote detailed notes about the dispute in his notebook – right down to Bondfield’s low design score. “Needs to be unanimous. Toigo voted against Bondfield design,” Mr. Aquino wrote. When asked by Zurich’s lawyers how he had such detailed information about a confidential meeting only a day after the argument, Mr. Aquino said he couldn’t recall precisely who told him. “I don’t know if it was feedback I was getting from Vas … or from my consultants.”

To end the impasse, Infrastructure Ontario and St. Michael’s took unprecedented steps, with the CEOs of both agencies exchanging e-mails and involving their boards. In the end, both agencies agreed to hire a third-party engineering consultant to review Bondfield’s bid. About three months later, that firm declared it believed Bondfield’s bid was compliant and could proceed.

Infrastructure Ontario signs hang on the construction hoarding outside St. Michael's in 2018.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The whistle is blown

In 2015, not long after Bondfield broke ground at the hospital, brown envelopes containing identical letters appeared in the mailboxes of four Globe and Mail journalists.

The author of the letters, which were unsigned, urged the reporters to look into the many ties between Mr. Georgiou and Mr. Aquino, and the awarding of the St. Michael’s contract.

Not long after, The Globe determined that, a year before Mr. Georgiou was hired at St. Michael’s, he had been fired from Infrastructure Ontario after he was implicated in a fraud at Toronto’s York University.

Court records showed that while he was a senior official at the procurement agency, he also controlled two construction companies that had issued invoices, totalling $65,000, to York for maintenance work. The problem was that neither company, both of which were owned by Mr. Georgiou’s family, had actually performed any work.

Mr. Georgiou was never charged criminally, but York sued him to recover the funds – a suit that was settled out of court. He said he had never personally profited from the scheme, but acknowledged distributing part of the proceeds, in cash, to a friend who had asked him to issue the invoices.

When The Globe asked St. Michael’s why it hired someone to oversee a $300-million procurement who had been embroiled in a fraud on a public university, the hospital had a simple answer: No one, including officials from Infrastructure Ontario, told it anything about this.

The Globe published a story on Sept. 15, 2015 about Mr. Georgiou’s role in the fraud. But the issues with him were much more extensive than $65,000 in false invoices.

After publishing its first piece, The Globe learned that, at the same time Mr. Georgiou had been evaluating bids for the St. Michael’s project, he had also been working on the side for companies owned by Mr. Aquino.

Throughout the RFQ stage of the procurement – the phase that Bondfield barely survived, if not for the rescoring of the submissions – Mr. Georgiou was co-ordinating with Bondfield, readying two buildings, owned in part by Mr. Aquino, for new commercial tenants.

The next Globe story, published on Sept. 24, 2015, detailed this conflict of interest, and Mr. Georgiou’s failure to disclose his ties to Mr. Aquino before the procurement.

On Nov. 12, 2015, St. Michael’s fired Mr. Georgiou for cause. The letter it sent him cited his involvement in the false-invoice scheme, as well as his failure to disclose his work for Mr. Aquino’s companies. And it issued him a stern warning: He was forbidden from using confidential information he had obtained during the procurement and from “providing services” to any company working on the hospital.

But the e-mails uncovered by Zurich show he was not deterred.

Bondfield's office in Vaughan. Bondfield's financing for St. Michael's project meant it wouldn't receive any taxpayer support from the public-private partnership until after the patient-care tower was finished.Cole Burston/The Globe and Mail

‘Something for Smooth’

Mr. Georgiou insisted he had been railroaded, and launched a wrongful dismissal lawsuit against St. Michael’s. But behind the scenes, e-mails show, he continued to act as an aide to Mr. Aquino – a whisperer who could help him navigate the politics of the hospital.

He resumed using his Bondfield e-mail address, bccldevelopment@bondfield.com, which had not come to light when he was fired, and was given a new BlackBerry by Mr. Aquino.

By 2016, the project was already falling into disarray. Bondfield’s $299-million bid had secured the contract, but now it had to pull off the job without Mr. Georgiou in a position of influence.

The company was in big trouble. The project was a public-private partnership, which meant Bondfield paid for all of the construction through a credit facility funded by a syndicate of banks, led by the Bank of Montreal. The company wouldn’t receive anything from taxpayers until it hit its first milestone – the completion of the patient-care tower. Bondfield was burning through cash. Suppliers, upset about payment issues, stopped delivering products. Subcontractors were furious.

On March 14, 2016, Mr. Aquino sought an audience with the leadership of the hospital, and was coached by Mr. Georgiou on his approach. Mr. Georgiou advised Mr. Aquino to keep his temper – well known throughout Ontario’s construction industry – in check. “Do not get upset or angry,” he wrote. “Speak Bay Street not Calabrese.”

The two men also believed, the e-mails show, they still had a key asset safely in place within the hospital.

On Jan. 5, 2015, just a few weeks before St. Michael’s announced it had finally selected Bondfield as the winner, Mr. Georgiou appointed Michael Mendonca as the hospital’s new vice-president of facilities. Mr. Mendonca, who also came to the hospital from Infrastructure Ontario, was to report to Mr. Georgiou and help oversee the project.

But the two men went back even further. Under questioning by Zurich’s lawyers, Mr. Georgiou confirmed they had been friends since high school. They were so close, in fact, that in many e-mails Mr. Georgiou referred to Mr. Mendonca by a nickname: “Smooth.”

Despite his unceremonious exit, Mr. Georgiou acted as a sort of liaison between Mr. Aquino and Mr. Mendonca. He passed messages from Mr. Aquino to Mr. Mendonca, and vice versa, through 2017. He even attended a dinner with Mr. Aquino, Mr. Mendonca and Steven Muzzo, the owner of Ozz Electric, one of Bondfield’s irate subcontractors, to try to mediate a resolution.

In 2017, more subcontractors walked off the job because of lack of payment. Mr. Aquino and Mr. Georgiou considered Mr. Mendonca their lifeline, internal Bondfield e-mails show.

On March 10, Mr. Aquino reached out to Mr. Georgiou when he heard from a Bondfield staffer that Mr. Mendonca was considering quitting: “Talk to Smooth. He is quitting?”

Mr. Georgiou replied three hours later, saying he spoke with Mr. Mendonca, who he said had agreed to “hang in.” He explained that Mr. Mendonca “felt trapped” because work on the project had come to a standstill, and that he was going to “get trashed” at the upcoming St. Michael’s board meeting.

Four months later, in July, Mr. Georgiou and Mr. Aquino were again concerned about Mr. Mendonca jumping ship. On July 27, Mr. Georgiou reached out to Mr. Aquino: “More importantly we need to connect on Mike and the BS going on down there and what we do to keep him.”

The next day, Mr. Aquino replied: “I am worried about Smooth.”

Mr. Mendonca declined to answer a list of questions from The Globe about why he continued to engage with Mr. Georgiou after he was fired. But in an e-mailed statement, he said he conducted himself “in a completely ethical and professional manner in all aspects.”

As for why Mr. Georgiou continued to involve himself in the project, and assert his influence with Mr. Mendonca, Mr. Georgiou insists he received no financial compensation for doing so.

During his examination, he was asked by Zurich lawyer Brian Kolenda: “Sir, you had been fired from the hospital some 18 months prior to this. Why on earth would Mr. Mendonca, you and Mr. Aquino, for any legitimate purpose, need to be discussing St. Mike’s at all?”

Mr. Georgiou replied: “I wanted to make sure that the project was a success, regardless of my departure from St. Mike’s.” He said there was “nothing untoward” about his continued involvement.

But Zurich alleges other e-mails show Mr. Georgiou was indeed trying to obtain some kind of compensation for Mr. Mendonca.

In December, 2017, there were several e-mails about Mr. Mendonca. On Dec. 8, Mr. Georgiou e-mailed Mr. Aquino: “I told smooth to do whatever he can do to help you and we will work things out.” Then, two days before Christmas, Mr. Georgiou e-mailed Mr. Aquino with a cryptic request: “Any chance to get something for Smooth today or tomorrow?”

Mr. Aquino replied with a terse, two-word answer: “Boxing Day.” Mr. Georgiou replied: “I will give him some more help tomorrow as he needs for xmas.” Asked by Zurich’s lawyers what “help” he provided to Mr. Mendonca, Mr. Aquino said he believed he gave him a panettone, the Italian sweet bread that is popular at Christmas. “So I think I gave him a panettone, and some wine, maybe a cognac bottle, that’s about it. But I didn’t give any cash to Mike Mendonca.”

Mr. Mendonca declined to explain what Mr. Georgiou was referring to when he asked Mr. Aquino to get “something” for him. However, in his e-mailed statement to The Globe he said he never received “cash or any other undisclosed payments from Mr. Aquino or anyone else.”

The reason cash payments were being raised in Mr. Aquino’s examination, was because of an e-mail he sent to Mr. Georgiou in 2017. On Feb. 14, 2017, the two men exchanged e-mails about a proposed casino development in Vancouver that one of Mr. Aquino’s neighbours was involved in financing. Mr. Aquino told Mr. Georgiou: “Your (sic) going to get a bousta if can make this deal.”

A bousta, or busta, is an Italian slang term often used to describe cash in an envelope. Pressed by Zurich’s lawyers, though, Mr. Georgiou said that’s not at all what Mr. Aquino meant. He said “bousta” was reference to a commission that Mr. Georgiou would earn as an adviser on the casino deal.

Mr. Aquino sits in his SUV at the Bondfield office last October. Infrastructure Ontario launched an investigation of his dealings with Vas Georgiou.Cole Burston/The Globe and Mail

‘Not compromised’

In the middle of all of this, after a 10-month investigation, a special committee of Infrastructure Ontario’s board issued the results of its investigation into Mr. Georgiou and Mr. Aquino. The report touted the number of hours it spent interviewing witnesses (144) and the number of documents it reviewed (3,785) and made several sweeping conclusions.

In its summary of key findings, the special committee declared that the procurement was not compromised. What’s more, it said its investigators – which consisted of a team from Toronto law firm Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP and forensic auditors from Cohen Hamilton Steger & Co. Inc. – had found no evidence “of any attempt to inappropriately influence the procurement.” Infrastructure Ontario paid Blakes $1.4-million for its work on the report.

For a number of people with inside knowledge about the procurement, the report’s findings were puzzling. Several sources with knowledge of Mr. Georgiou’s interventions at the RFQ and RFP stages – interventions that benefited Bondfield – who spoke with The Globe said they were simply never approached by the investigators. The Globe is not naming these sources because they were not authorized to speak publicly about the procurement.

Infrastructure Ontario continues to defend its conclusions.

In response to e-mailed questions from The Globe, Linda Robinson, the then-chair of Infrastructure Ontario’s board and a former partner at Osler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, said: “I am not going to comment on matters that were reviewed at great length and in painstaking detail by the legal and accounting firms five years ago.”

Michael Lindsay, the new CEO of Infrastructure Ontario, said in an e-mailed statement that, because the agency selects winners by consensus as part of a committee, it is “virtually impossible for individuals to influence the outcome.”

As for the investigators’ failure to uncover the secret e-mails between Mr. Aquino and Mr. Georgiou, or the evidence of the home renovations and other alleged benefits, Mr. Lindsay chalked that up to the limitations of private investigators. “It must be recognized that neither the legal nor forensic accounting teams had the power to compel documents and testimony from unwilling parties.”

This is not entirely accurate. Law firms that specialize in white-collar investigations often turn to the courts to compel the production of documents. They also sometimes obtain a court’s permission to execute civil search warrants on residences and businesses – what is known as an Anton Piller order.

As for St. Michael’s, the hospital settled its wrongful dismissal lawsuit with Mr. Georgiou. The terms of the settlement are confidential, but the evidence unearthed by Zurich contains a hint about what Mr. Georgiou received.

Despite being terminated with cause – the result of which was supposed to be the full termination of all of his compensation – Mr. Georgiou received his full salary for another 18 months.

Pension documents provided by St. Michael’s to Zurich show that Mr. Georgiou received his salary from Nov. 12, 2015 to May 12, 2017 – payments totalling $477,000.

Ms. Divell, the Unity Health spokeswoman, declined to comment on the payments to Mr. Georgiou.

In its statement, Unity Health characterized Zurich’s lawsuit as an “attempt to get out of its obligations under the surety bonds,” and noted that the healthcare network has countersued the insurer.

For its part, Zurich said, through its lawyer, that it disagreed with that assertion. “This litigation is about corruption in a publicly funded procurement process.”

As for the project itself, St. Michael’s has opened six floors of the new tower for patient care, as well as a COVID-19 vaccination clinic. The top two floors remain under construction, Ms. Divell said.

“In the meantime, our focus will remain on what has been our priority for more than 130 years and what matters even more right now – caring for those who need us most during this unprecedented pandemic,” she said.

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.