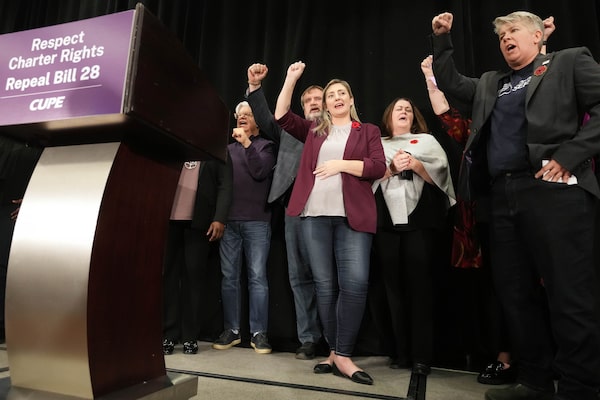

OPSEU president JP Hornick, right, and CUPE-OSBCU president Laura Walton, centre, chant along with other union heads during a press conference in Toronto on Nov. 7, 2022.Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press

Throughout her tenure so far as president of the Ontario Public Service Employees Union, JP Hornick has been fighting legal, cultural and ideological battles – all, she says, in an attempt to create a “different kind of unionism.”

Asked during a recent interview to describe what she means by “different,” she said the union she envisions is one that roots out favouritism, makes equity a core tenet in decision-making and prioritizes member gains in collective bargaining over internal political wins or appeasing employers.

“When I ran for the presidency, I ran on the notion that I’m a member, like everyone else. I’ve never sat on the executive board. I saw the presidency as building a movement to take back our unions,” Ms. Hornick said.

OPSEU, which represents 180,000 public-sector workers in Ontario, is one of Canada’s largest unions. Ms. Hornick and her second-in-command, vice-president and treasurer Laurie Nancekivell, took office in April, 2022, marking the first change in the organization’s presidency in well over a decade. The union’s previous president, Warren (Smokey) Thomas, served for 15 years.

Explainer: How do strikes work in Canada? An intro to unions and labour laws

Reforms like the ones Ms. Hornick is pursuing have stymied many in the labour movement over the years. Union culture has traditionally been top-heavy, hierarchical, white and male. But conditions have changed: Prolonged inflation and a cost-of-living crisis have workers demanding more from their union leadership, and paying more attention to the way decisions are made. The time may be right for change.

Over the past year, Ms. Hornick has pushed through amendments to OPSEU’s constitution, aimed at changing the structure of the union’s governance. But the most public of her battles began in January when OPSEU launched a lawsuit against Mr. Thomas and two other former union executives for allegedly using millions of dollars of union cash and assets to enrich themselves.

Mr. Thomas filed a countersuit against OPSEU, alleging that Ms. Hornick and her supporters were pursuing him for political reasons, and that they were “incensed” that he had appeared in 2021 alongside Ontario Premier Doug Ford, a conservative, for an announcement about an increase to the minimum wage.

Inside the emboldening of Canada’s unions

Two months later, OPSEU expanded its accusations against the other two ex-union bosses named in the suit, former vice-president and treasurer Eddy Almeida and former financial administrator Maurice Gabay. The union alleged that Mr. Almeida, Mr. Gabay and a third former union employee, Stephen Ward, had selectively awarded union contracts to associates and received kickbacks from them. None of the allegations have been proven in court, and all four former officials have denied the accusations against them.

The lawsuits came about as a result of a third-party forensic audit that Ms. Hornick and Ms. Nancekivell greenlit when they took office. The accusations led to upheaval within OPSEU. While a majority of union members and staff appeared supportive, a few were suspicious of Ms. Hornick’s and Ms. Nancekivell’s motivations.

Larry Savage, a labour studies professor at Brock University, said Ms. Hornick’s decision to litigate could strengthen the relationship between the union and its membership. “Especially now, establishing trust between leadership and membership is foundational to building union power,” he said. “That’s why it was important for Hornick and her team to shine a light on past improprieties and commit to making things right.”

But Ms. Hornick has often found herself defending her intentions. The forensic audit has allowed the union to know where it stands financially and establish sounder fiscal practices, she told thousands of members at OPSEU’s annual convention last month, to a round of applause.

Conversations about the role of the labour movement in social justice issues were central in Ms. Hornick’s home when she was growing up, she told The Globe and Mail.

She began her career at George Brown College in 1997 as a professor at the School of Labour, and soon got involved in her own union local. In 2012, she was elected to the bargaining team of the College of Applied Arts and Technology, which is part of OPSEU. Five years later, in 2017, she became chair of that team and ran a province-wide strike for college faculty that lasted five weeks. “That’s where things really took off for me,” she said.

During Mr. Thomas’s time as OPSEU president, Ms. Hornick said, she and others felt that power was too centralized at the union, and that member activism was discouraged.

“When I was actively involved in the union in 2017 we were at a crossroads with OPSEU. We really felt, how is this union actually supporting me?”

She started organizing courses and developing tools for members, based on guidance from progressive labour organizations like U.S.-based Labour Notes.

Many unions across North America, Ms. Hornick said, lack transparency, engage in cronyism and compromise with employers when it is politically advantageous for their leaders to do so.

“So we gathered a whole bunch of like-minded people and said to ourselves, we can either try and take back our union by organizing to fix it, or just do nothing. That’s what I mean when I say ‘a different kind of unionism.’ This is a long project,” she said.

At OPSEU’s convention in April, members voted through two major constitutional changes that Ms. Hornick supported. First, the union added seven equity seats to its board, one for each of seven internal committees that represent marginalized groups, including Indigenous people.

Second, members greenlit a governance review, a step toward changing the leadership structure of the union. Ms. Hornick said this could lead to less concentrated power at the top of the organization.

“What I think people will start to see soon is a shift in how the organization is run – a feeling that there is no longer nepotism, favouritism in hiring and political favours. We are committed to moving out of this transactional model of unionism,” she said.

Her methods have met resistance from some OPSEU staff members. In late November, Gord Longhi, president of the Administrative Staff Union, which represents OPSEU’s supervisors and higher-ranking administrative employees, sent an e-mail to his members warning them about an “unprecedented” series of suspensions of employees by OPSEU’s new leadership.

He called the suspensions “disturbing” and accused Ms. Hornick and Ms. Nancekivell of not being transparent about the reasons for them. One of the staff members who was suspended and eventually dismissed was Mr. Ward, who was named in OPSEU’s March lawsuit.

Ms. Hornick said she has been working to improve her relationship with the ASU. “There are a number of outstanding issues with the ASU, but they are all being discussed,” she said.

Lois Boggs, the president of the Ontario Public Service Staff Union (OPSSU), which represents most other employees of OPSEU, said that on the whole her members are feeling safer with the new leadership.

“No workplace is perfect. But staff definitely feel like if they speak up, they are not going to get fired or disciplined for that. And I think JP and Laurie have really helped in creating this environment,” she said.

But Ms. Boggs added that the lawsuits have been distracting, particularly because some OPSEU employees remain upset and angry over the accusations levelled at Mr. Thomas and Mr. Almeida.

Ms. Hornick is aware that some people see her plan as self-interested, or as “just another corporate strategy.” But she said she is confident that most members agree that OPSEU’s foundation needs to be re-examined, and its cracks exposed.

“Being a union and an employer can be weird,” she added. “There is tension. But I always ask myself, what kind of boss do I want to be? Who am I really fighting for? It’s not myself. It’s the bigger cause. That’s what we are working towards.”