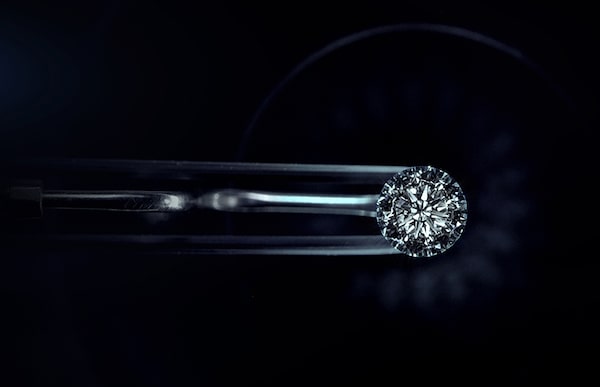

A cut and polished ALTR lab grown diamond.ALTR Created Diamonds/Handout

Earlier this year, Frédéric Arnault, the lanky twentysomething head of LVMH’s Tag Heuer brand and potential heir to the Paris-based luxury empire, presented a novelty at the Watches and Wonders fair in Geneva that would have been previously unthinkable for a company dealing in the real and rare: a 350,000-Swiss-franc ($470,000) timepiece featuring diamonds grown in a laboratory.

Carrera Plasma, is the most expensive product in the 160-year history of Swiss-based Tag Heuer.Supplied

Frédéric Arnault, chief executive of TAG Heuer.ALEX WELSH/The New York Times

The glitzy little number, named the Carrera Plasma, is the most expensive product in the 160-year history of Swiss-based Tag Heuer. It boasts a 44-millimetre sandblasted aluminum case set with 48 diamonds and a rhodium-plated brass base dial covered with a single block of polycrystalline diamond. Topping it off is a crown made from a 2.5-carat diamond at the side. And all these diamonds are lab grown – that is, produced by people in a factory through a controlled technological process, not created naturally by geology and pulled out of the earth.

“We thought, ‘We want to be the first to come with a true, ambitious, innovative vision using lab-grown diamonds,’” Mr. Arnault told an interviewer at the fair. “This is a showpiece of savoir-faire and technology.”

It was more than that, though. Whether he deliberately wanted to or not, Mr. Arnault and LVMH – the Paris-based multinational that owns a vast stable of high-end consumer brands, including Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Tiffany and Veuve Clicquot – almost instantly turned the traditional notion of luxury on its head. What’s more, it made the diamonds part of the watch’s function, not only the sparkly add-on of years past.

Things are shifting in the US$87-billion-a-year global diamond jewellery market. Tag’s endorsement is a symbol of legitimacy for lab-diamond producers. More broadly, it’s a sign their industry is maturing – paradoxically stretching toward the highest reaches of luxury while still cultivating mass appeal.

At the retail level, interest is building as the lab-made diamond industry educates consumers about its stones, which are chemically identical to mined diamonds but cost far less. Popular retailers such as JCPenney and Swarovski carry lab-made diamonds, while higher-end jewellers such as Birks Group are trying them out.

In the space of a few short years, lab-grown has exploded from 0 per cent of the total global diamond jewellery market to about 8 per cent to 10 per cent. Over the next five years, it could claim a share as high as 15 per cent, according to Paul Zimnisky Diamond Analytics.

The reasons for the growth aren’t difficult to understand. Lab-cultured stones are generally cheaper than mined ones, for one. They’ve also largely neutralized two big negatives associated with mined diamonds – political and environmental.

Mined diamonds have been trying to shake their ties to conflict and corruption for years in producing countries such as Angola and Zimbabwe. More recently, their natural footprint – and the huge amounts of equipment and resources it takes to yield the final product – has also come under scrutiny.

The biggest challenge now for lab-grown producers isn’t proving they can make real diamonds. Rather, it’s finding and hiring enough skilled scientists and technicians to make them quickly and reliably enough in quality and quantity to meet orders – and doing so while maintaining the value of the product.

Lab-made diamond price relative to mined diamond, by size

Price of a lab-made diamond as a percentage of a natural one of equal size

0.5 carat

1 carat

1.5 carat

3 carat

De Beers’s Lightbox lab-made diamond jewelry first available for sale

100%

80

60

40

20

0

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Note: 3-carat lab-made goods were not readily available on the market until around 2020.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: PAUL ZIMNISKY

DIAMOND ANALYTICS

Lab-made diamond price relative to mined diamond, by size

Price of a lab-made diamond as a percentage of a natural one of equal size

0.5 carat

1 carat

1.5 carat

3 carat

De Beers’s Lightbox lab-made diamond jewelry first available for sale

100%

80

60

40

20

0

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Note: 3-carat lab-made goods were not readily available on the market until around 2020.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: PAUL ZIMNISKY

DIAMOND ANALYTICS

Lab-made diamond price relative to mined diamond, by size

Price of a lab-made diamond as a percentage of a natural one of equal size

0.5 carat

1 carat

1.5 carat

3 carat

De Beers’s Lightbox lab-made diamond jewelry first available for sale

100%

80

60

40

20

0

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Note: 3-carat lab-made goods were not readily available on the market until around 2020.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: PAUL ZIMNISKY DIAMOND ANALYTICS

Price comparison of lab-made and

mined diamonds

As of Q2 2022, by size

Lab-made

Mined

0.5 carat

5.1 mm

$670

$1.4K

1 carat

6.4 mm

$1.6K

$6.7K

1.5 carat

7.4 mm

$3K

$15.4K

3 carat

9.3 mm

$12.2K

$72.8K

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: THE MVEye;

BLUE NILE; BRILLIANT EARTH

Price comparison of lab-made and mined diamonds

As of Q2 2022, by size

Size 7 ring

17.3 mm

$670

Lab-made

0.5 carat

5.1 mm

Mined

$1.4K

$1.6K

1 carat

6.4 mm

$6.7K

$3K

1.5 carat

7.4 mm

$15.4K

$12.2K

3 carat

9.3 mm

$72.8K

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: THE MVEye;

BLUE NILE; BRILLIANT EARTH

Price comparison of lab-made and mined diamonds

As of Q2 2022, by size

$72.8K

Lab-made

Mined

$15.4K

$12.2K

$6.7K

$1.4K

$1.6K

$3K

$670

0.5 carat

5.1 mm

1 carat

6.4 mm

1.5 carat

7.4 mm

3 carat

9.3 mm

Size 7 ring

17.3 mm

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: THE MVEye; BLUE NILE; BRILLIANT EARTH

Virginia Drosos, chief executive of Akron, Ohio-headquartered Signet Jewelers Ltd., the world’s biggest jeweller, told analysts on a conference call in March that lab-created diamonds will be among the top three trends driving sales for merchants this year.

Benny Landa, a growly-voiced Israeli-Canadian who launched one of the industry’s pioneering producers, Israel-based Lusix, sees things playing out far beyond that. In June, his company announced it had won a new US$90-million investment from several companies, including LVMH.

The news landed at JCK Las Vegas, the continent’s biggest annual jewellery trade event, like a clap of thunder. It’s believed to be the first time a top luxury-associated brand has made an investment in lab-grown diamonds. American business magazine Forbes declared: “LVMH Makes it Official: Lab-Grown Diamonds are Luxury.”

Mr. Landa says it’s inevitable lab-made diamonds will one day be the standard stones people buy in stores and the mined product will disappear, dying a slow death at the hands of untenable production costs and a focus on sustainability. It just might take several decades.

“It’s inevitable. You can’t fight it,” Mr. Landa said. His argument: No traditional industry has ever managed to halt technological development. “People don’t like change because they’re not part of it. … But there’s no technology that can be held back.”

High-end watchmakers, like many other top jewellery manufacturers and retailers, have largely avoided lab diamonds because they’re perceived to lack the scarcity, and therefore exclusivity, of mined diamonds. What Mr. Arnaud is betting, though, is that the unique properties and technological possibilities inherent in the lab-grown product will forge a design identity people will seek out. In other words, it’s what lab-grown can do that makes it valuable, not where it comes from.

The Carrera Plasma isn’t about replacing traditional mined diamonds with lab-grown in Tag’s catalogue offerings, Mr. Arnault says. Rather, it’s a decision to use one advantage of the lab-made product: to grow a stone to end-use specifications to create new configurations and textures for timepieces. “To build and create something never seen before,” as he put it.

Making such a pricey, premium timepiece would have been difficult, if not impossible, with mined diamonds, the Tag CEO says. That’s because a much larger mined diamond would be needed to cut it to the same shapes achievable by the lab-grown product. What’s more, the mined diamond runs the risk of breaking in the process.

For Danish jewellery giant Pandora, it’s a different calculation. It’s been roughly a year since the manufacturer and seller caused global media delirium when it proclaimed it would turn exclusively to lab-grown diamonds for its mass-market jewellery, becoming the first big jeweller to turn its back on mined stones. With one news release in May, 2021, Copenhagen-based Pandora gave the lab-made product nearly unprecedented attention, shining a spotlight on a sector that has been waiting years for its “I’m here” moment.

The headlines were hair-raising: “The World’s Largest Jewelry Brand is Ditching Mined Diamonds,” CNN wrote. France’s Le Figaro asked: “Les diamants resteront-ils éternels?” (Will Diamonds Stay Forever?), implying this might be the beginning of the end for the mined gems.

That hasn’t happened, and it isn’t likely to happen in this lifetime, according to industry players and experts interviewed for this story. Mined diamonds still command healthy prices on global markets, a trend fuelled by decreasing supply and the lack of new major production on the horizon. If that scarcity continues at the same time lab-grown availability grows, analysts such as Paul Zimnisky say the two will compete directly less and less over time.

Almost since they were first discovered, diamonds pulled from the ground have been marketed as a wondrous gift from nature, with prices out of reach for most of humanity. If you wanted to give one as a token of love, you saved for it. If you couldn’t or wouldn’t, you were led to believe you were missing out. Precious and scintillatingly beautiful, “diamonds are a girl’s best friend,” Marilyn Monroe sang in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

A mid-growth type IIA diamond following weeks in WD Lab Grown Diamonds' growth chambers.WD Lab Grown Diamonds/Handout

Diamond is pure crystalized carbon, the product of carbon atoms slowly self-assembling more than 150 kilometres deep in the Earth’s mantle at temperatures of more than 1,000 C. Over millions of years, some diamonds eventually push close enough to the Earth’s surface to be pulled out by people – a process that has built much wealth for some companies and societies, and led to devastating political and humanitarian outcomes for others, particularly in Africa.

Russia’s war on Ukraine is adding yet another twist. Russian mining giant Alrosa PJSC supplies about a third of the world’s raw gems, and sanctions against the company by Western countries mean many regular buyers won’t touch them even if they are processed in India.

Promoters of lab-grown diamonds say that’s benefiting them because no one wants “conflict diamonds” and proving provenance in the mined industry is complicated because stones change hands so many times. Others say it will force the mined diamond industry to act quickly and introduce better tracking methods to document where stones come from. Those efforts are already under way.

Companies making lab-grown diamonds are honing their technology and processes in countries such as India, China, Israel and the United States. Production is growing as quickly as they can add it. Canada could soon be in the mix, too. Producers are now scouting in British Columbia and elsewhere for manufacturing sites – there are none currently – in search of cheap and clean power. (Energy is the biggest variable production cost for a lab diamond grower.)

On the marketing side, the industry has been sustained by a singular idea for decades: that diamonds are rare. And no company pushed that idea more than De Beers Group, the London-based mining giant started by Cecil Rhodes in 1888. For more than a century after its inception, De Beers controlled the vast majority of diamond distribution in the world and was considered a monopoly.

To maintain demand for its diamonds, De Beers controlled the supply. And it did something even more genius: It used advertising to define diamonds as a symbol of romantic love and devotion. The slogan “A diamond is forever” was created for De Beers in the late 1940s. Sixty years later, Advertising Age named it the best ad slogan of the 20th century.

Lab-grown diamonds have existed since the early 1950s, when they were made using a technique known as the high-pressure, high-temperature process. But these early diamonds were typically grain-sized and used for industrial applications that showcased their hardness, including cutting and grinding other materials. Eventually they found other uses, such as electronics. De Beers has a business arm called Element Six for this purpose.

It wasn’t until a few years ago, however, that technology advanced to the point where gem-quality diamonds could be made in a lab. The kind of stones you could use for jewellery. Chemical vapour deposition technology is where the most significant recent advances have taken place.

Amish Shah, chief executive of New York-based ALTR Created Diamonds.ALTR Created Diamonds/Handout

When gem-quality, lab-grown diamonds came to the market in earnest starting around 2016, “the conversation around rarity started cracking,” says Amish Shah, a third-generation diamonteer and CEO of New York-based ALTR Created Diamonds. The company was an early producer and promoter of lab-grown diamonds, and sells to several retailers, including Canada’s Birks and Berkshire Hathaway’s Borsheims jewellery store in Omaha, Neb.

Many retailers were reluctant to carry lab-grown diamonds at the beginning, Mr. Shah says. The majority refused to even talk about them, influenced by a view that the stones were synthetic, and therefore fake. “You could sit across from a retailer and the moment you opened the conversation they would say no,” Mr. Shah says. “Distributors, same thing. They didn’t even know about it. They’d never seen them. But the fear of this change was causing the problem.”

The conversation changed in 2018, when the U.S. Federal Trade Commission ruled that an earth-mined gem and a lab-grown one are both diamonds. “The Commission no longer defines a ‘diamond’ by using the term ‘natural’ because it is no longer accurate to define diamonds as ‘natural’ when it is now possible to create products that have essentially the same optical, physical and chemical properties as mined diamonds,” the FTC said. Still, under the regulator’s rules, sellers have to label them with a qualifier such as lab-grown to make clear to buyers it’s not the mined product.

Unleashed from their “fake” reputation, however, lab-grown diamonds quickly took off. Consumers started buying them, attracted by the value proposition. More producers started operations. The industry gained more legitimacy when De Beers’s Element Six launched a gem-quality, lab-grown consumer diamond business that same year. Lightbox supplies gems to popular online diamond retailer Blue Nile.

A diamond produced by WD Lab Grown Diamonds, one of the pioneers in the lab-grown diamond space.WD Lab Grown Diamonds/Handout

Last year, privately held U.S. lab-grown producer Diamond Foundry raised US$200-million in a deal that gave it a US$1.8-billion valuation. Foundry said it would use the money to increase production exponentially. In a cheeky claim to authenticity, Foundry named its direct-to-consumer business “Vrai,” French for “true” or “real.”

Celebrities have jumped on the industry trend, too. Hollywood actor Leonardo DiCaprio, who starred in the 2006 action thriller Blood Diamond (which threw a spotlight on gems mined in war zones and sold to finance warlords) is an investor backing Diamond Foundry.

“We’re actually seeing a very significant expansion of the consumer pie for diamonds,” said Marty Hurwitz, CEO of the MVEye, a market research and consulting firm for the gem and jewellery industry. “At first, the traditional mined diamond industry was quite scared. And you know, in their typical fashion put out a lot of negative messages about [lab-made gems]. But what’s evolving now is the pie is actually growing because younger, new consumers, next-gen consumers who were unlikely to buy a mined diamond, are now actually coming into jewellery stores and seeing both.”

WD Lab Grown Diamonds was another pioneer. The Washington-area company, founded by British jeweller Clive Hill and owned in part by private equity firm Huron Capital, announced its first commercially available diamonds in September, 2012. It held the record for the world’s biggest gem-quality, lab-grown diamond at 9.04 carats, but that has been eclipsed several times.

Research consistently shows that consumers cite price as the No. 1 reason they choose lab-grown diamonds. They’re cheaper in part because they’re made in a controlled environment. In addition, fewer people are involved at each step of the production and processing than a mined diamond, which typically changes hands several times through extraction, cutting, polishing and setting.

Sue Rechner. CEO of WD Lab Grown Diamonds.Hugo Garcia/Handout

“When you’re in a lab, you know everything,” says Sue Rechner, WD’s CEO. “You know how much your chamber costs. You know how much your people cost. You know how long the diamond takes to make. You know what the market value is. So you have the ability to create business cases around fixed information.”

Worth is generated by the product but also by the specific processes under which it grew.

Take WD, considered a higher-end producer. The company’s product is made in the U.S. It’s as-grown and not chemically altered by acid washes or other treatment, as the mined product can be. Finally, the diamonds are climate neutral, with third-party auditing to confirm there are no effects on land, water resources and air quality. All of that generates value, Ms. Rechner says.

Creating high quality, lab-grown diamonds also comes with significant technical barriers, the CEO says. You need the equipment, the science, the software tools to manage the process, and most of all, the human resources expertise, she says. There are very few diamond scientists around the world who have enough scientific knowledge to be able to do this well. “You can’t really walk into a diamond chamber company, give them $200,000, walk out, plug it in and make diamonds,” Ms. Rechner said. “Because of all these technical barriers.”

Producing the quantity and consistent quality customers seek is even harder, she says. “You can put something in and get very low colour and poor quality. But it’s going to take years of developing your specific trade secrets to be able to output consistently high quality, high colour, larger stones. It’s quite difficult.”

The winners in this game will be producers that secure the services of scientists who are available and experienced, says the MVEye’s Mr. Hurwitz, who is also a WD director. “Lock them up early in the race. That’s what’s happening right now.”

Human resources in this case extends far beyond hiring. One panelist at a recent industry forum said that in India, PhD-level scientists for lab-grown companies are protected by armed security guards to avoid kidnappings. “That secret sauce is something that companies that are successful at it really guard closely,” Mr. Hurwitz said.

The WD Lab Grown Diamonds facility in Washington, D.C.WD Lab Grown Diamonds/Handout

Diamond mines are often gigantic operations, with open pit craters stretching hundreds of metres across and down into the earth. Diamond laboratories, by contrast, are decidedly more low-key affairs, with the footprint to match.

Lusix’s lab-making factory in Rehovot, Israel, is a one-storey building packed with cube-shaped, black-coloured machines, arranged in long rows, that make diamonds. Each is the size of a fridge, with various cables attached that provide power and connect controls. The infrastructure is similar to that used to make semiconductors, except here they make diamonds instead of chips.

Creating a rough, lab-grown diamond starts with a seed, which is a flat square flake of actual diamond. It’s put into a small reaction chamber, which is injected with carbon-rich gas, such as methane. Then the gas is excited with high-powered microwave radiation to more than 5,000 C. That’s as hot as the surface of the sun.

At that temperature, the gas turns into a glowing plasma and the molecules rip themselves apart, freeing the carbon atoms from which they’re made. Those atoms bond to the surface of the seed and grow the diamond, one layer at a time. After three or four weeks, you have a finished diamond.

“It’s nature that grows the diamond, just like nature does the self-assembly of the diamonds below the surface of the Earth,” Mr. Landa said. “We don’t know how to do that. It’s a natural phenomenon. All we do is create the environment to let nature do its thing. In many ways, it’s like growing mushrooms or tomatoes.”

Lusix has almost 100 machines in its first facility, each capable of cooking dozens of diamonds at once. Some machines are used for research and development. The company has plans for 400 production machines and dozens more R&D machines as it puts a second facility into service this summer in the city of Modi’in, Mr. Landa said. The company has a 30-megawatt solar farm to power its operations and markets its gems as “sun grown diamonds.”

But if Lusix, WD and ALTR are the premium end of the lab-grown business, making big stones like clockwork for regular customers, there are many more companies at the lower end of the spectrum producing smaller, more mass-market gems at lower prices.

This is where the industry is going as it matures, says Mr. Zimnisky: toward a split between the lowest-cost lab-made diamonds sold more as “fashion” jewellery and higher-priced “fine” jewellery supported by strong branding and marketing efforts.

Supply projections for mined

rough diamonds

Millions of carats

Existing mines

Optimistic scenario

New mines/projects

Conservative scenario

Forecast

180

Change from

2020 to 2030

1% to 2%

150

120

90

-2% to -1%

60

2018

2020

(estimate)

2023

2026

2030

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: BAIN & COMPANY

Supply projections for mined rough diamonds

Millions of carats

Existing mines

Optimistic scenario

New mines/projects

Conservative scenario

Forecast

180

Change from

2020 to 2030

1% to 2%

150

120

90

-2% to -1%

60

2018

2020

(estimate)

2023

2026

2030

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: BAIN & COMPANY

Supply projections for mined rough diamonds

Millions of carats

Existing mines

Optimistic scenario

New mines/projects

Conservative scenario

Forecast

180

Change from

2020 to 2030

1% to 2%

150

120

90

-2% to -1%

60

2018

2020

(estimate)

2023

2026

2030

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: BAIN & COMPANY

Right now, lab-grown producers make an estimated 7 to 9 million carats of rough diamonds each year for use in jewellery, according to Mr. Zimnisky’s data. He predicts this will grow up to 25 per cent annually through at least 2026. By comparison, diamond miners currently produce about 120 million carats a year, of which about 72 million carats is earmarked for jewellery.

Price is one key reason why many consumers choose lab-grown diamonds. The market price as of May for a one-carat diamond, one of the most popular sizes for engagement rings in the United States and Canada, was US$1,620 for a lab-made gem versus US$6,675 for the mined option, Zimnisky research shows.

The price difference is growing wider. On the one end, the supply of lab-made diamonds is increasing as more producers get into the game, while technology improvements are boosting yields and lowering growing costs. On the other, though they’ve experienced some swings, mined diamond prices have generally held up over the years and hit an all-time high in January. That same one-carat diamond costs more today than it did in 2016. By contrast, the lab-made specimen is less than a third the price it was six years ago.

Mr. Zimnisky figures that price disparity will only widen, chiefly because of the supply side of the equation. The supply of mined diamonds is limited by nature and by whether it’s economical to pull them out of the ground profitably. There is only one new major mine on the horizon and it will likely take a period of sustained price growth to make it worth tapping new resource discoveries.

An ALTR lab grown rough diamond, with polycarbons removed. At the retail level, interest is building as the lab-made diamond industry educates consumers about its stones.ALTR Created Diamonds/Handout

By comparison, lab-made diamonds are manufactured and “theoretically unlimited in supply,” Mr. Zimnisky said. The analyst gives the example of manufactured rubies, emeralds and sapphires, which have been on the market for decades, with price differentials to the mined gems of as much as 95 per cent.

The notion of rarity, therefore, hasn’t really been broken since lab-grown diamonds came to market. And because an expert with the proper equipment can distinguish a mined diamond from a lab-made one, producers and retailers of mined diamonds still have difference and singularity as selling points – even if their industry still arguably has to overcome long-held concerns about the environmental and social consequences of diamond mining. Cartier and Bulgari are among the luxury brands that have so far eschewed lab-made diamonds to stick with the mined product.

Mr. Zimnisky says the real big-money potential for lab-created diamonds might be expanding their industrial uses. As for jewellery, their biggest impact might be, as Pandora has recognized, to democratize the industry by making beautiful jewellery accessible to the world’s burgeoning middle class.

“There’s a lot of people in China that would like a natural diamond and maybe they can’t afford it but they can afford a lab diamond,” Mr. Zimnisky said. “So, I think there’s going to be this kind of whole new customer base for this product that didn’t exist in the diamond jewellery space before.”

Jean-Christophe Bedos, president of Montreal-based Birks, provides some historical perspective to support that view. When smartwatches gained popularity in the early 2000s, there was much debate over whether they would destroy quartz movement-based watches in the same way quartz disrupted and almost toppled the traditional mechanical watch industry. They didn’t, he says. Rather, they attracted a new group of buyers and created a new market.

Estimated middle class, mass affluent and high-net-worth (HNW) segments in China and India

Millions of households

Affluent and HNW

Middle class

China

India

320

300

279

259

239

212

132

115

99

84

70

51

2020

2022

2024

2026

2028

2030

Forecast

estimate

Notes: Middle class is defined as households with annual disposable income from US$15,000 to US$45,000 for China and from US$10,000 o US$25,000 for India; mass affluent and high-net-worth segment is defined as households with annual disposable income over US$45,000 for China and over US$25,000 for India.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: BAIN & COMPANY

Estimated middle class, mass affluent and high-net-worth (HNW) segments in China and India

Millions of households

Affluent and HNW

Middle class

320

China

India

300

279

259

239

212

132

115

99

84

70

51

2020

2022

2024

2026

2028

2030

Forecast

estimate

Notes: Middle class is defined as households with annual disposable income from US$15,000 to US$45,000 for China and from US$10,000 o US$25,000 for India; mass affluent and high-net-worth segment is defined as households with annual disposable income over US$45,000 for China and over US$25,000 for India.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: BAIN & COMPANY

Estimated middle class, mass affluent and high-net-worth (HNW) segments in China and India

Millions of households

Affluent and HNW

Middle class

320

China

India

300

279

259

239

212

132

115

99

84

70

51

2020

2022

2024

2026

2028

2030

estimate

Forecast

Notes: Middle class is defined as households with annual disposable income from US$15,000 to US$45,000 for China and from US$10,000 o US$25,000 for India; mass affluent and high-net-worth segment is defined as households with annual disposable income over US$45,000 for China and over US$25,000 for India.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: BAIN & COMPANY

The same thing happened after cultivated pearls were introduced a century ago, Mr. Bedos says. Before then, only a very few wealthy and privileged people could afford one pearl, never mind a strand. At a dinner party around 1916, French jeweller Pierre Cartier famously exchanged a double-strand pearl necklace, believed to be the most expensive one of its kind in the world at the time at more than US$1-million, for a neo-Renaissance mansion on New York’s Fifth Avenue. The building today houses Cartier’s U.S. headquarters.

Canadian consumers are showing a growing interest in lab-grown diamonds, Mr. Bedos says. His big fear is that they become “commoditized,” that lab-made diamond producers create a volume business driven by price, which spreads across the sector. That, he says, would kill the emotion that has been so central to jewellery for centuries.

“You can introduce lab-made, and I really think there is space for that,” Mr. Bedos said. “But if you kill the dream, why do it? If you kill the dream of the people who want to buy a stone and please a loved one and really have the feeling that they are doing something beautiful. It’s a commitment, it’s an engagement. It’s a symbol of eternity.”

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.