The Royal Bank Plaza, located on the northwest corner of Front St. West and Bay St. in Toronto’s Financial District, sold for $1.1-billion last year.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

A year into the fastest campaign to hike interest rates in decades, the commercial real estate sector is deadlocked.

In one corner, the world’s most sophisticated private real estate investors, including Canadian pension plans, say scores of properties they own are worth hundreds of millions of dollars each and have held most of their value. In the other, investors are dumping shares of publicly-traded real estate investment trusts (REITs), particularly those that own skyscrapers, because they don’t think such lofty values still make sense. In Canada, the national vacancy rate of office towers just hit an all-time high, and in New York, there are enough empty offices to fill 26 Empire State Buildings.

Who’s right? That’s the trillion-dollar question looming over private investors in particular as they gauge whether to start marking down the value of their property portfolios more aggressively. It is a complex puzzle: Not all commercial properties are equal; deals that set market prices are at a low ebb; and there is a healthy dose of discretion permitted in the way private investors weigh the matrix of variables.

Macro trends must also be factored in. The sudden runup in interest rates has collided with the long tail of a global pandemic that has altered how and where people work, shop and live – all of which is coupled with the threat of an economic downturn that could upend a sector that has been fuelled by cheap money for more than a decade.

“You see what’s happening with private real estate versus what’s happened to the price of REITs – there’s just a massive valuation difference there that isn’t easy to explain, quite honestly,” Bert Clark, chief executive officer of public-sector pension manager Investment Management Corporation of Ontario, said in an interview.

The answer impacts trillions of dollars worth of office towers, malls, warehouses and apartment buildings, affecting everyone from banks that lend to the sector – including U.S. regional lenders whose share prices are already under siege – to the millions of Canadians whose pensions are managed by major property owners such as the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS).

Because so much is at stake, the standoff is getting testy. Pressed to justify their optimism for the real estate sector, private investors are starting to push back against the naysayers. “My honest view is people are overreacting quite materially,” Blake Hutcheson, OMERS’ CEO, said in an interview. “I think private valuations are much closer to reality than publics.”

Valuing real estate portfolios is tricky work, and private owners – as well as the outside experts they hire to vet their numbers – have leeway in how they appraise properties. By design, most private investors are patient owners with long-term leases who look not only at what a property would fetch today, but its future potential based on cash flows, replacement costs and the values of comparable buildings.

Over time, that makes their results less volatile. But it also raises eyebrows when markets plunge and private valuations don’t follow. The $21.2-billion real estate division of OMERS returned 13.6 per cent in 2022. Ivanhoé Cambridge, the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec’s real estate arm that manages $48-billion worth of properties globally, was not far behind with a 12.4-per-cent gain last year.

Those returns are at odds with the performances of publicly-traded REITs. Shares of Allied Properties REIT AP-UN-T, once viewed as one of Canada’s most desirable REITs because it owns offices in downtown cores of cities such as Toronto and Montreal, many of which are in heritage-style buildings that have charm, are down 62 per cent from their prepandemic high. And the Canadian REIT universe – which encompasses everything from skyscrapers to rental apartment buildings to suburban shopping centres – is trading around a 30-per-cent discount to its net asset value, according to research from CIBC World Markets.

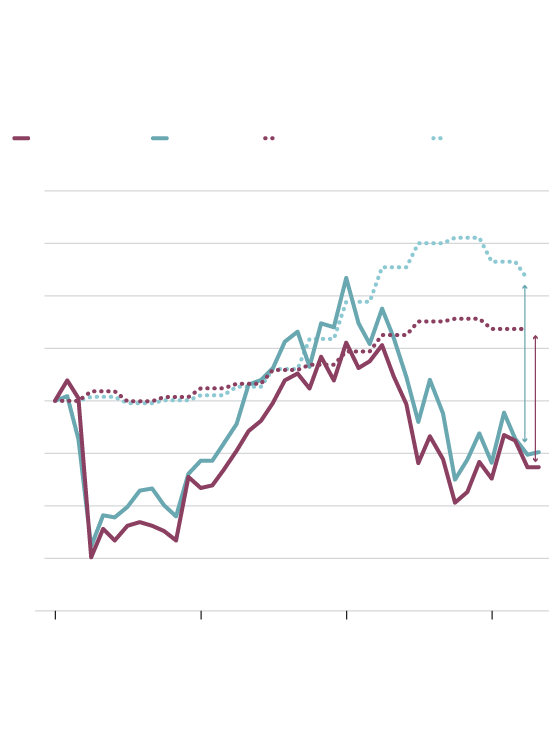

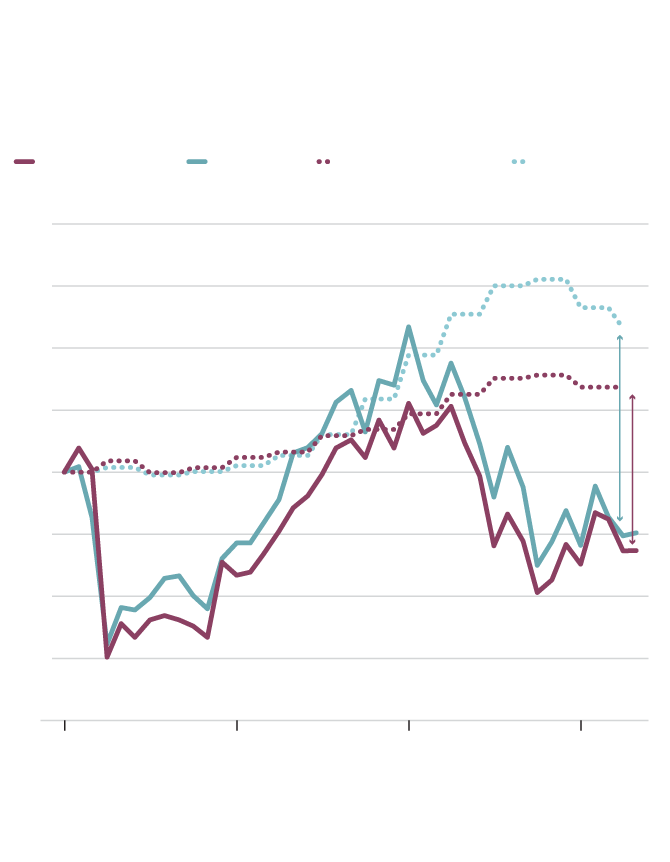

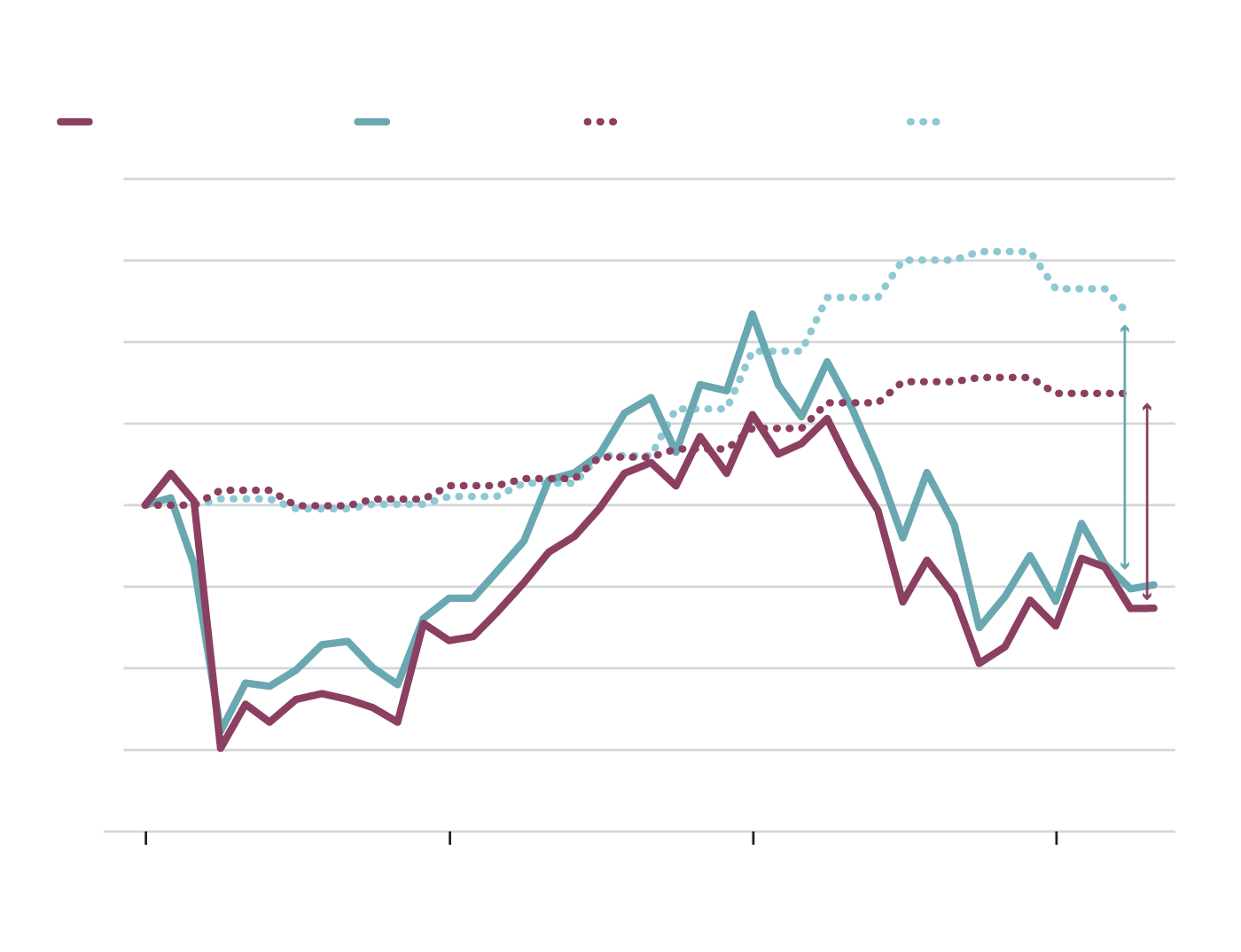

MSCI, a financial market research firm, tracks the difference between publicly-listed and private, or unlisted, real estate in Canada and the U.S. Its latest figures show the gap in public and private values is 37 per cent in Canada, and 30 per cent in the U.S.

Comparing price movements for listed

and unlisted real estate

Price/asset value level (Index: Dec. 2019 = 100)

Canada listed

U.S. listed

Canada unlisted

U.S. unlisted

140

130

120

110

30%

37%

100

90

80

70

60

2020

2021

2022

2023

JOHN SOPINSKI/the globe and mail,

source: msci real assets

Comparing price movements for listed

and unlisted real estate

Price/asset value level (Index: Dec. 2019 = 100)

Canada listed

U.S. listed

Canada unlisted

U.S. unlisted

140

130

120

110

30%

37%

100

90

80

70

60

2020

2021

2022

2023

JOHN SOPINSKI/the globe and mail,

source: msci real assets

Comparing price movements for listed and unlisted real estate

Price/asset value level (Index: Dec. 2019 = 100)

Canada listed

U.S. listed

Canada unlisted

U.S. unlisted

140

130

120

110

30%

37%

100

90

80

70

60

2020

2021

2022

2023

JOHN SOPINSKI/the globe and mail, source: msci real assets

These value gaps are now so large that they are hard to ignore, yet few people are willing talk publicly about them. Multiple companies that specialize in commercial real estate valuations declined to comment for this story, citing tensions between their public and private clients.

Amid this chaos, private owners do occasionally acknowledge the winds have shifted. Last year Royal Bank Plaza, the tower that houses the headquarters of Canada’s largest lender, Royal Bank of Canada RY-T, sold for $1.1-billion to the Spanish billionaire behind the Zara fashion retail chain. Its sellers were OMERS’ real estate arm, Oxford Properties, and its co-investor, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board. At OMERS’ annual meeting in April, Mr. Hutcheson told pension plan members that if they tried the same sale again now, “I would think we’d get $300-million or $400-million less.” That’s a 30- to 40-per-cent drop, in line with public market valuations.

The question, then, is at what point must these estimates be integrated into financial models, if at all? Private real estate owners have long argued that they are private by design, because it allows them to smooth out market volatility, but they can’t ignore public investors forever. Many institutional shareholders doing the public-market selling are just as large, smart and sophisticated.

What no one contests is that the recent rise in interest rates is a dominant variable for both camps. The real estate sector is one of the most sensitive to interest rate changes, and the speed at which central banks across the West have hiked rates is extremely rare.

Higher rates have, in simple terms, taken the punch bowl away from the real estate party. In the decade leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, most commercial real estate was on fire because ultralow rates made mortgages extremely cheap. Central bank intervention to keep rates artificially low during the pandemic only exacerbated this trend.

Now that the pandemic is no longer a global emergency and benchmark interest rates have jumped at least four percentage points in both Canada and the U.S., investors are taking stock of all that has transpired. As the dust settles, with Canadian and U.S. central banks suggesting they are hitting pause, it is clear there are stark differences between the different asset classes of commercial real estate.

Industrial properties such as warehouses, manufacturing plants and distribution centres are hot – particularly in Canada, where the national vacancy rate fell to a record low of 1.6 per cent at the end of 2022, according to CBRE Group Inc., and is now only a tad higher. The supply of properties is so tight that some landlords have been able to raise rents more than 100 per cent in tenant turnovers and lease renewals.

Rental apartment building owners have also performed well, because their supply is constrained in many major cities across the U.S. and Canada. Boardwalk REIT BEI-UN-T, a major rental apartment owner in Calgary, reported earnings this week and its average rent increase when a tenant turned over last quarter was 15 per cent.

The office sector, though, is very clearly hurting, as are retail properties, albeit to a lesser extent. Office towers were among the hottest commercial real estate to own heading into the pandemic, with a vacancy rate of just 1.2 per cent in downtown Toronto, but white-collar workers have embraced hybrid work accommodations and the national occupancy for office buildings in Canada hit an all-time high of 17.7 per cent in the first quarter, according to CBRE.

“The fundamentals are brutal. Some of these buildings are never coming back,” Jeff Olin, the co-founder of Vision Capital Corp., which manages real estate investment funds, said in an interview. He still thinks some office towers are great, but when it comes to private owners’ estimates, “there’s certainly denial, that’s for sure.”

Despite the headwinds, major property owners, including Brookfield Asset Management and Blackstone Inc., argue the process of valuing commercial real estate today is nuanced. Even in the office sector, they stress that quality matters. Newer towers with modern amenities, known as Class A buildings, are seeing higher occupancy rates and rising rents, while older, less well-maintained buildings, often located in suburban areas – the Class B and C inventory – are emptying out.

There has been “an absolute bifurcation of the real estate market,” Connor Teskey, president of Toronto-based Brookfield Asset Management Ltd., said on a conference call last week.

To this end, Slate Office REIT SOT-DB-T and True North Commercial REIT TNT-UN-T, both of which largely own Class B properties predominately in Ontario, slashed their monthly payouts in recent weeks by 70 per cent and 50 per cent, respectively.

A dearth of property sales has also complicated things. Because there are now so few yardsticks to use when pricing a deal, even the most prominent and experienced investors can’t agree on what properties are worth.

In the first quarter of 2023, commercial property deal volume in Canada dropped 52 per cent year over year, according MSCI Real Assets, with the office sector plummeting 86 per cent and the retail sector dropping 66 per cent. In the U.S., first-quarter office deal volume dropped below the depths of the pandemic, hitting a pace not seen since the immediate aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis.

Although property sales will eventually rebound, offering some new benchmarks, there is a wildcard in this valuation puzzle: a wave of mortgage refinancings. Although private holders have the financial wherewithal to think long-term, they finance their property purchases with shorter-term debt, often on five-year terms, and some of it comes due each year. Most of the new debt replacing it is more expensive because the previous mortgages were locked in when rates were lower, or at ultralow rates in some cases, and owners will have to ask themselves if it makes sense to put more money into their properties to stave off defaults or sales under duress.

Even Brookfield BN-T, which regularly touts the high quality of its properties, has already defaulted on two loans for office towers in Los Angeles worth a combined US$755-million in February, and on another US$161-million mortgage for a dozen office buildings in Washington in April. It is possible the defaults are strategic, in order to negotiate better deals with lenders, but they also likely wouldn’t have happened if the market was still hot.

The coming refinancing cycle will also affect banks, which are the dominant lenders in commercial real estate. In the U.S., recent deposit woes at regional lenders are already shrinking the pool of available credit for property owners, and in Canada the federal banking regulator has ranked commercial real estate as the third most acute of nine key risks it is tracking this year, citing offices as well as construction and development assets as those under the most pressure. About 1.2 per cent of all loans at Canada’s largest banks are underpinned by office buildings.

Banks have tougher lending standards than they did in past crises, and their risks are spread over multiple sectors of real estate, so Canada’s lenders are expected to withstand commercial real estate shocks, Mike Rizvanovic, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, said in a recent note to clients. But if they and their U.S. peers pull back on lending, it could force distressed sales for real estate owners who can’t refinance.

Private owners acknowledge this scenario is possible, and that it would push down real estate valuations. But they argue they have the financial heft and scale to withstand short-term shocks. “If you can stay at the table, time will be your friend,” said Mr. Hutcheson, the OMERS CEO.

Recalling his estimate of Royal Bank Plaza’s market value today, he stressed it would only be realized if the buyer was forced to sell now. “As a private owner, I think it’s worth everything they paid for it,” he said.