The federal government acknowledged what many Canadians are fretting about as they cope with affordability challenges: the increasing odds the country will go into recession.

Ottawa published its fall economic statement on Thursday, outlining several risks to the economic outlook, including a “more aggressive” reaction to inflation from the U.S. Federal Reserve, via higher interest rates, and “widespread volatility” in markets for stocks and bonds. The trajectory for Canada’s economy is uncertain, and in turn, that’s created uncertainty for the path of public finances.

With that in mind, here are five highlights from Thursday’s statement.

Slowing growth

The federal government surveys the private sector for their outlooks on economic growth, which helps to inform their fiscal planning and projections. For the fall economic statement, that survey was conducted in early September. Since then, the economic outlook – already fraught – has continued to deteriorate as central banks try to tame persistent inflation.

As a result, the Department of Finance published a “downside scenario” in which “elevated inflation becomes more deeply entrenched,” leading to even more monetary policy tightening from central banks. That scenario would see Canada enter a “mild recession” in the first quarter of 2023; real gross domestic product would fall by 1.6 per cent from peak to trough.

For 2023 as a whole, real GDP would fall 0.9 per cent, compared to an expansion of 0.7 per cent that private-sector economists had indicated roughly two months ago. In a downturn, the government would bring in less revenue from income taxes, including from both businesses and workers. Program expenses would also rise, largely because persistent inflation is driving up benefits that are indexed to inflation, such as the Canada Child Benefit. Those twin forces, in turn, would leave the federal government running larger deficits.

The deficit

The federal deficit is waning, following two years of explosive spending related to the pandemic, combined with sky-high inflation that’s boosted government revenues. But the outlook is tinged with uncertainty as the economy slows – especially so in the event of a recession.

The fall economic statement projected a deficit of $36.4-billion in the current 2022-23 fiscal year, improving from a forecasted $52.8-billion in the spring budget. It was, however, not as slim a deficit as many private-sector economists expected. For instance, Bank of Nova Scotia had projected a shortfall of $31.7-billion, while the Parliamentary Budget Officer had predicted $25.8-billion.

On Thursday, the federal government announced new spending of $22.1-billion over six years, plus an additional $8.5-billion during that time as a provision for “anticipated near-term pressures.”

If the “downside scenario” of economic contraction plays out, deficits would swell. For this fiscal year, the deficit could wind up at $49.1-billion, then expand to $52.4-billion in 2023-24 – far different from the baseline assumption of ebbing deficits that, eventually, lead to a surplus in 2027-28.

Buyback tax

The government has paved the way for taxation of stock buybacks, in which a corporation buys its own stock from existing shareholders. The intention is to introduce a corporate tax of 2 per cent that would apply to the net value of share buybacks by public corporations in Canada. The plan is similar to one contained in the Inflation Reduction Act, which U.S. President Joe Biden signed into law in August. Starting next year, the U.S. will levy a 1-per-cent excise tax on share buybacks. The Canadian tax would go into effect on Jan. 1, 2024. The federal government said this measure would raise an estimated $2.1-billion in revenue over five years, “while also encouraging corporations to reinvest their profits in their workers and business.” More details will be announced in the 2023 spring budget.

Affordability

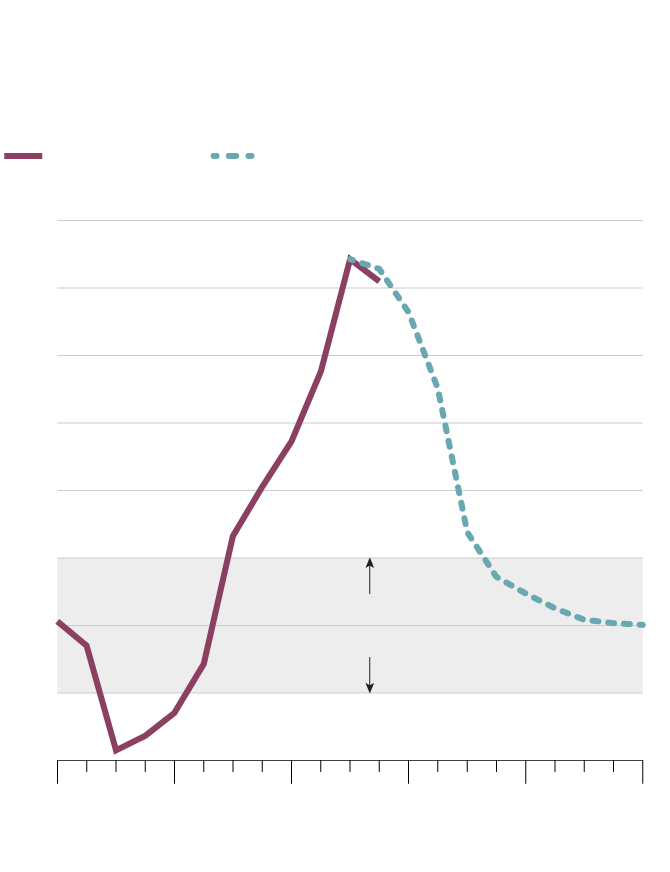

Actual and forecast consumer

price inflation, Canada

Year-over-year percentage change

on quarterly basis

Actual data

Forecast

8%

7

6

5

4

3

Inflation target

band (1–3%)

2

1

0

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

SOURCE: DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE CANADA

Actual and forecast consumer

price inflation, Canada

Year-over-year percentage change on quarterly basis

Actual data

Forecast

8%

7

6

5

4

3

Inflation target

band (1–3%)

2

1

0

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

SOURCE: DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE CANADA

Actual and forecast consumer price inflation, Canada

Year-over-year percentage change on quarterly basis

Actual data

Forecast

8%

7

6

5

4

3

Inflation target band (1–3%)

2

1

0

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

SOURCE: DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE CANADA

Since its spring budget, the Liberals have unveiled billions in new spending to help Canadians with lofty inflation, including a doubling of the Goods and Services Tax credit for six months, which more than 10 million people are slated to access.

More support was offered on Thursday. For instance, the fall economic statement proposed to make all Canada Student Loans and Canada Apprentice Loans interest-free on a permanent basis, including loans currently being repaid. The change, which would start on April 1, 2023, would cost $2.7-billion over five years and slightly more than $550-million a year thereafter.

The fall statement also proposed $4-billion over six years to automatically issue payments of the Canada Workers Benefit to people who qualified for it the previous year. The CWB is a refundable tax credit to help those who are working and earn a low income.

Clean tech tax credit

The fall economic statement proposes a refundable tax credit for investments in clean technology. This would apply to capital costs for electricity generation systems; stationary electricity storage systems that do not use fossil fuels in their operation, such as batteries and thermal energy storage; industrial zero-emission vehicles; and so on.

The tax credit would be equal to 30 per cent of capital costs for companies that “adhere to certain labour conditions,” for which the Finance Department will hold consultations. Otherwise, it would be a credit of 20 per cent. The credit would be available as of next year’s budget – that date will not be confirmed for several months – and start to phase out in 2032. The tax credit is projected to cost $6.7-billion over five years.