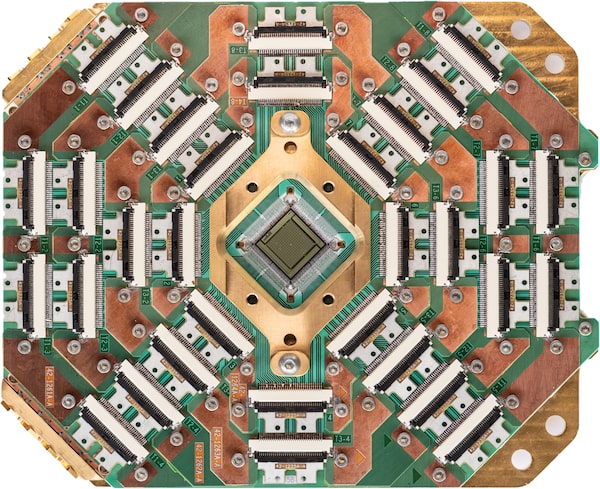

A quantum computer chip from D-Wave Quantum Inc.Courtesy of D-Wave Systems Inc.

D-Wave Quantum Inc. QBTS-N, one of Canada’s most audacious and controversial technology companies, is facing a cash crunch six months after going public, some investors warn.

“They need a strategy to show they can pay their bills and how they’ll survive” and create shareholder value, said Daniel Wolfe, president of Montclair, N.J.-based 180 Degree Capital, owner of 911,938 D-Wave shares. “This company has a liquidity issue.”

Burnaby, B.C.-based D-Wave has raised more than US$350-million from investors. It has also received tens of millions of dollars in federal aid and features prominently in the government’s quantum strategy.

D-Wave has spent 24 years developing machines that draw computing power from the quantum effects of subatomic particles, and it promises that they will one day outperform the world’s most powerful computers.

The company’s technology is advanced enough that D-Wave generates millions in revenue delivering results that 63 clients, including Mastercard Inc., Deloitte and Canadian grocer Save-On-Foods, are willing to pay for, solving complex optimization problems such as scheduling workers and launching loyalty programs. Rival quantum computers won’t be able to do the same for years. “The era of commercial quantum computing is here today, and D-Wave is leading the charge,” chief executive officer Alan Baratz told a D-Wave conference last month.

But D-Wave is in the early days of building a business, and its technology has not reached full potential. That will require years and more investment. Meanwhile, rivals are building machines that could surpass D-Wave’s capabilities.

The company’s predicament is a reminder that turning breakthrough technology into commercial success is rare. It requires translating scientific advances into working products, generating demand from paying customers and raising enough from patient investors. Falling behind is a constant threat.

For D-Wave, mastering quantum mechanics may be the easy part.

A rush for the exits?

To secure its future, D-Wave tried to raise US$340-million last year by merging with the New York Stock Exchange-listed special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, DPCM Capital Inc. But with tech stocks out of favour, D-Wave raised a fraction of that. Its shares have lost 84 per cent of their value since the merger last August.

Geordie Rose, founder of D-Wave Systems Inc., standing in front of the D-WaveOne Quantum Computer.

Now, owners of D-Wave equity dating to when it was privately held are about to get their first chance to sell when a lock-up lifts Sunday. That group includes Amazon.com Inc. founder Jeff Bezos, Goldman Sachs, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency’s venture capital arm, Fidelity Investments, Japan’s NEC Corp. and majority shareholder Public Sector Pension Investment Board (PSP) of Montreal, which has sunk more than US$120-million into D-Wave.

How legacy shareholders act could affect D-Wave’s fragile cash situation. D-Wave had US$13.8-million cash last Sept. 30. It generated US$4.8-million in revenue in the first nine months of 2022, while operating expenses were US$40.9-million. D-Wave has said fourth-quarter revenue will be US$4.2-million or less.

It forecasts sales will rise rapidly, reaching US$550-million in 2026. Getting there will be expensive, though, with estimated negative cash flow of US$139-million and heavy losses in 2023 and 2024.

The company’s key funding source is an equity line of credit with Chicago’s Lincoln Park Capital Fund. It permits D-Wave to draw up to US$150-million in exchange for the issuance of shares. It’s not cheap: D-Wave paid a commitment fee of US$2.6-million in October and issues stock to Lincoln Park at or below market price.

But D-Wave can only access a limited amount of cash daily, and Lincoln Park can’t own more than 9.9 per cent of the company, whose market capitalization has dwindled to US$176-million. That would cap Lincoln Park’s ownership at US$17.4-million of stock at current price levels.

There is another snag: If the stock sinks below US$1 a share, D-Wave is prohibited from using the credit line. Shares closed at US$1.58 on Friday. It’s unclear how many unlocked investors might sell or what that could do to the stock. Holders of millions of shares paid 2 US cents apiece or less and could profit selling even now.

“There’s going to be a rush to the exits by some and who knows what happens to the price then,” said former D-Wave director Michael Brown, who owns 70,866 shares. Calgary angel investor Chen Fong, with 68,503 shares, said: “I suspect I will probably just sell and take my losses.”

“They need a notable improvement on the balance sheet in the not-too-distant future,” said Richard Shannon, an analyst with Craig-Hallum Capital in Minneapolis. D-Wave has warned it may scale back operations or discontinue them if it can’t find new financing.

In response to questions about liquidity and efforts to shore up its finances, Mr. Baratz said in an e-mailed statement that D-Wave is exploring “additional financing while we continue to focus on growth.” But until D-Wave generates significant revenue, he said, “we expect to finance our cash needs through public and/or private equity offerings” including its line of credit “and/or debt financings or other capital sources, including strategic partnerships.”

The infinity machine

Despite D-Wave’s funding woes, it has the early commercial lead in a quantum-computing race that includes Google GOOGL-Q, International Business Machines Corp. IBM-N and Canada’s Xanadu Quantum Technologies Inc. to build the first machine that can outperform supercomputers.

Early theorists believed it would take decades to build such a computer, which, instead of reading 1s or 0s, would harness the quantum mechanical properties of subatomic particles that can be in multiple states at once.

But D-Wave co-founder Geordie Rose embraced emerging theories and set out to make a machine using a process known as quantum annealing. He believed D-Wave could get to market quicker with a more limited but practical machine that could perform optimization tasks such as financial modelling and material simulation.

The approach was controversial; D-Wave had doubters in the scientific community about whether its machine was a quantum computer. But it attracted investors and buzz. A Time cover story called Mr. Rose’s computer “the Infinity Machine.”

D-Wave’s initial plan was to sell machines, which were expensive and complicated to host and run: They required months of installation to meet specific operating conditions that enabled their semiconductors to run at temperatures colder than deep space.

There were few buyers; early machines were of limited use beyond giving scientists at well-funded research organizations, including NASA, Google, Lockheed Martin Corp. and the U.S. Los Alamos National Laboratory, a chance to tinker with cutting-edge technology.

PSP got involved after portfolio manager Philippe St-Jean, who has a PhD in physics, took an interest in D-Wave. In 2014, PSP invested $25-million, a rare direct deal into a Canadian tech company, and became D-Wave’s top funder thereafter.

“We’re a long-term investor so we have to think about what will be important technology down the road. Like, 15 to 20 years down the road,” Mr. St-Jean, who has since left PSP, told The Globe and Mail in 2018.

Meanwhile, the industry’s future shifted to the cloud. In 2017, D-Wave hired Mr. Baratz as chief product officer. The Silicon Valley veteran had led Sun Microsystems Inc.’s efforts in the 1990s to transform Java from a nascent programming language into the internet’s main software-writing platform.

At his direction, D-Wave provided online access to its technology by creating software and developer tools. Once he was promoted to CEO in 2020, Mr. Baratz told staff to focus on cloud deals and stop selling the shed-sized machines.

D-Wave Systems Inc. Advantage, a shed-sized device that houses a quantum computer chip.Courtesy of D-Wave Systems Inc.

Still, D-Wave struggled to raise financing. In late 2018, as it was about to secure a major commitment from Chinese internet giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Canadian authorities arrested the chief financial officer of Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd., also based in China. Alibaba pulled out.

Existing investors injected US$30-million to tide D-Wave over. It then raised US$40-million in 2020 from backers PSP, BDC Capital, Goldman Sachs and newcomer NEC. The deal cut its valuation to less than US$170-million from US$450-million. Other investors saw their holdings mostly wiped out.

Mr. Baratz figured going public was the answer to D-Wave’s cash needs. Merging with a SPAC was the best course for a promising company in a nascent industry that needed time to mature, he said last year. Two other quantum-computer companies had recently launched SPAC IPOs, including IonQ Inc., which raised more than US$600-million.

SPACs were controversial for several reasons, including the fact that investors in the “blank cheque” paper entities could redeem their shares before the mergers. On Feb. 8, 2022, D-Wave unveiled its combination with DPCM, which had raised US$300-million. D-Wave pledged to raise US$40-million from private investors. With $340-million, it could fund itself for years.

Redemptions at other SPACs climbed as the process unfolded. By June, Mr. Baratz wanted the Lincoln Park line of credit as backup, but DPCM CEO Emil Michael worried the threat of dilution would increase SPAC redemptions, regulatory filings show. So they redrew the deal and D-Wave agreed to cut the minimum required funding to US$30-million from US$115-million.

By the deal’s close last August, 97 per cent of DPCM’s shareholders had redeemed their stock, leaving just US$9-million for D-Wave. That was less than the merger’s US$11.5-million deal costs. More than half the US$40-million raised by D-Wave went to repay a venture loan.

D-Wave’s funding plan had flopped, and it now had the added costs of running a public company. The SPAC deal “did not solve their financial issue,” Mr. Brown said.

The company’s future remains uncertain. Can it find funding at a time when investors are hesitant to back unprofitable tech companies? Will it slash costs like other tech companies? Will PSP step up again? (A PSP spokeswoman declined to comment.)

D-Wave has a lot of technology and 200 patents and “I think someone will take it out,” said Mr. Fong.

Selling D-Wave could present a dilemma for the government, which has championed Canada’s quantum industry as part of its innovation agenda. Ottawa has faced criticism for doing little to help build homegrown tech giants. D-Wave may be challenged, but it is Canada’s most commercially advanced quantum company.

Ottawa could thwart foreign takeovers and is entitled to immediate repayment, upon a change of control, of a $40-million contribution to D-Wave in 2020 if the government doesn’t approve of the deal. But would it do so if such a move threatened D-Wave’s existence?

D-Wave’s predicament “is inevitable gravity coming down on a 24-year-old startup which has raised a tonne of money and hasn’t got a lot to show for it,” said Mr. Brown.

Sean Silcoff

Sean Silcoff