Telesat currently has a phase-1 Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite, which is communicating with ground stations such as this facility in Allan Park, Ont.ryan carter/The Globe and Mail

With plans to launch a web of almost 300 small satellites, Telesat Canada is taking on big U.S. names as it jockeys to be the leader in a race to deliver faster internet from space.

The Ottawa-based company wants to build a “constellation” of satellites that would each orbit the Earth multiple times a day from about 1,000 kilometres above the planet, creating a local communications network in space that could quickly send vast amounts of data to and from users and ground stations that connect back to the broader internet.

Fifty-year-old Telesat has emerged as one of the leaders in the field of low-Earth orbit, or “LEO,” satellite broadband proposals. The company already has 17 satellites in geostationary orbit, which are about 36,000 kilometres above the planet and synchronized with the rotation of the Earth so they remain in a fixed position. These support satellite TV and telecommunications services, with users pointing antennas toward the satellite to receive the signals.

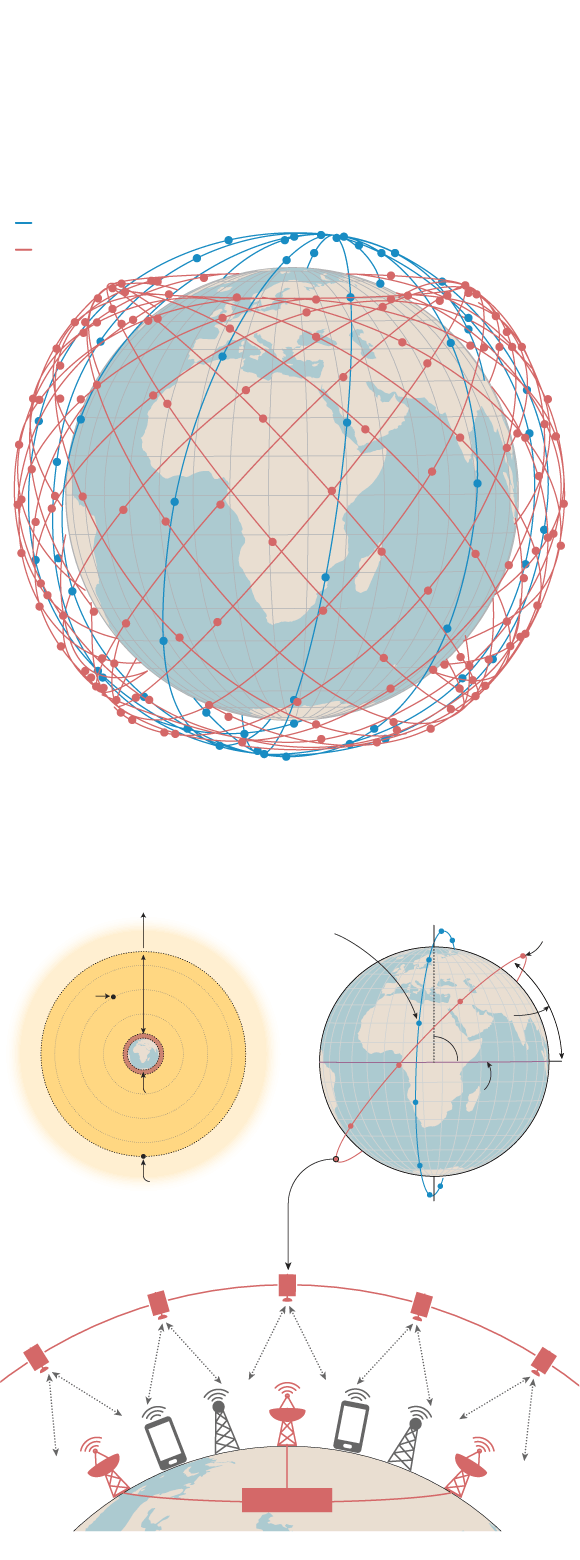

Telesat’s proposed LEO (low-Earth orbit) satellite constellation

Telesat wants to build a "constellation" of satellites that orbit the globe from about 1,000 km above the planet. This would create a communications network that delivers faster internet from space than traditional "geostationary" satellites, which are about 36,000 km above Earth.

ORBIT CLASSIFICATIONS

The height of the orbit determines the satellite’s orbital velocity. Satellites closer to Earth move more quickly. A satellite in geostationary orbit matches the Earth’s rotational speed and seems to stay in place.

High-Earth orbit

GPS

20,200 km

Mid-Earth orbit

2,000–35,780 km

Low-Earth orbit

180–2,000 km

Geostationary orbit

35,780 km

THE CONSTELLATION

Telesat’s global constellation will consist of 292 satellites, 72 in Polar orbit plus 220 in Inclined orbit. The mix of different orbits is meant to offer global coverage, with the satellites in polar orbit giving better northern coverage and the inclined-orbit satellites covering mid-latitude regions.

Polar orbit

Inclined orbit

ORBIT INCLINATIONS

Inclination is the angle between the equator and the satellite orbit. An inclination of zero degrees is an equatorial orbit. An inclination of 90 degrees is an orbit directly over the North and South Poles.

North Pole

Polar

orbit

Inclined

orbit

90°

Orbital

inclination

0°

Equator

South Pole

The internet

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

NASA; TELESAT; THE ECONOMIST

Telesat’s proposed LEO (low-Earth orbit) satellite constellation

Telesat wants to build a "constellation" of satellites that orbit the globe from about 1,000 km above the planet. This would create a communications network that delivers faster internet from space than traditional "geostationary" satellites, which are about 36,000 km above Earth.

ORBIT CLASSIFICATIONS

The height of the orbit determines the satellite’s orbital velocity. Satellites closer to Earth move more quickly. A satellite in geostationary orbit matches the Earth’s rotational speed and seems to stay in place.

High-Earth orbit

GPS

20,200 km

Mid-Earth orbit

2,000–35,780 km

Low-Earth orbit

180–2,000 km

Geostationary orbit

35,780 km

THE CONSTELLATION

Telesat’s global constellation will consist of 292 satellites, 72 in Polar orbit plus 220 in Inclined orbit. The mix of different orbits is meant to offer global coverage, with the satellites in polar orbit giving better northern coverage and the inclined-orbit satellites covering mid-latitude regions.

Polar orbit

Inclined orbit

ORBIT INCLINATIONS

Inclination is the angle between the equator and the satellite orbit. An inclination of zero degrees is an equatorial orbit. An inclination of 90 degrees is an orbit directly over the North and South Poles.

North Pole

Polar

orbit

Inclined

orbit

90°

Orbital

inclination

0°

Equator

South Pole

The internet

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

NASA; TELESAT; THE ECONOMIST

Telesat’s proposed LEO (low-Earth orbit) satellite constellation

Telesat wants to build a "constellation" of satellites that orbit the globe from about 1,000 km above the planet. This would create a communications network that delivers faster internet from space than traditional "geostationary" satellites, which are about 36,000 km above Earth.

THE CONSTELLATION

Telesat’s global constellation will consist of 292 satellites, 72 in polar orbit plus 220 in inclined orbit. The mix of different orbits is meant to offer global coverage, with the satellites in polar orbit giving better northern coverage and the inclined-orbit satellites covering mid-latitude regions.

Polar orbit

Inclined orbit

ORBIT CLASSIFICATIONS

ORBIT INCLINATIONS

The height of the orbit determines the satellite’s orbital velocity. Satellites closer to Earth move more quickly. A satellite in geostationary orbit matches the Earth’s rotational speed and seems to stay in place.

Inclination is the angle between the equator and the satellite orbit. An inclination of zero degrees is an equatorial orbit. An inclination of 90 degrees is an orbit directly over the North and South Poles.

North Pole

Polar

orbit

Inclined

orbit

High-Earth orbit

90°

GPS

20,200 km

Mid-Earth orbit

2,000–35,780 km

Orbital

inclination

0°

Low-Earth orbit

180–2,000 km

Equator

Geostationary orbit

35,780 km

South Pole

The internet

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NASA; TELESAT; THE ECONOMIST

But its LEO plans represent a major shift in both technology and ambition for Telesat. The constellation closer to Earth would be able to carry more data with far less lag time and, in addition to doing more for key enterprise clients such as ships, airplanes and governments, the company says it could one day help address the problem of unreliable and expensive rural and remote internet access.

Telesat’s main rivals in the LEO race are Tesla Inc. founder Elon Musk’s SpaceX (the rocket-launching company that has also started a new satellite internet operation dubbed Starlink) and OneWeb, a high-profile U.S. startup that is backed by Japan’s SoftBank, owner of Sprint Corp. The trio are among about a dozen companies that have won approvals to operate LEO constellations from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission, a crucial regulatory authority for any global satellite proposal.

“To me, we’re the obvious company to tackle LEO and make it work,” Telesat chief executive Dan Goldberg said in a recent interview, rattling off a list of what he sees as advantages: Telesat’s long history of satellite operations and technical expertise, its understanding of different markets for the service and relationships with existing clients, its experience with regulators and its priority access to valuable spectrum (the invisible radiowaves that carry communications signals).

Technologist Steve Young works in the a control centre at the Allan Park facility.ryan carter/The Globe and Mail

Finally, he said, Telesat knows how to raise money, and lots of it. “We have a very good track record of creating equity value and a very good track record of raising billions of dollars of debt, so we’re well known to the capital markets.”

Telesat announced two moves forward on Thursday, revealing agreements with Loon, a subsidiary of Google’s parent company Alphabet Inc., as well as Blue Origin, a spaceflight company started by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. Loon operates a fleet of high-altitude balloons that deliver communications services, and Telesat plans to adapt Loon’s network operating system for its LEO satellites. It also announced plans for multiple satellite launches on a new Blue Origin rocket expected to have its maiden flight in 2021. (Telesat says one rocket launch can carry more than 30 satellites.)

Telesat has one test satellite in orbit, plans to announce a primary contractor for its satellites later this year (it’s weighing bids from Airbus and a consortium of Thales Alenia Space and Maxar Technologies Inc.) and wants to be “in service” by the end of 2022, Mr. Goldberg said.

A wave of LEO satellite proposals first cropped up in the 1990s and a series of bankruptcies followed. The resurgence of such plans in the past half decade is partly because of advances in technology and lower manufacturing costs as well as the availability of key bands of spectrum, said Inigio del Portillo, a PhD candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who wrote a technical paper on LEO proposals last year.

But it has become a crowded field. “I think that there’s way too many companies trying to do it. I’m not sure there’s a market for all of them,” he said, adding, “I think probably they will consolidate at some point."

Bill Acheson and Gordon Jarvis close the door of the Telemetry, Tracking, and Commanding (TTAC) antenna being used to communicate with Telesat's Phase 1 LEO satellite.ryan carter/The Globe and Mail

Telesat, OneWeb and SpaceX – along with Washington, D.C.-based LeoSat, which is focused solely on enterprise customers – are likely the leaders right now, Mr. del Portillo said. Smaller players have also won FCC approval, including Toronto-based Kepler Communications Inc.

In its 2018 budget, the Canadian government committed $100-million over five years to LEO projects, and Telesat has been lobbying for more. The company, along with other players in the aerospace industry, wrote a letter to Finance Minister Bill Morneau in January urging Ottawa to allocate funding to its LEO project. Telesat argues it will help Canada remain a leader in space technology and also “bridge the digital divide” by bringing high-quality internet to an estimated 4.5 million Canadians who do not currently enjoy such access.

Broadband access for rural and remote residents – many of whom are Indigenous – is a key promise found in most of the large LEO constellation proposals, although Mr. del Portillo is skeptical. “They always mention rural internet, but I think it’s more like PR [public relations],” he said, adding that enterprise customers are likely to be the primary clients.

Since the satellites are constantly moving and handing off traffic as they pass over users, on-Earth receivers need multiple antennas controlled by electronics to work. It’s expensive technology and Mr. del Portillo added that it likely needs to be cheaper before consumer broadband is a viable LEO market.

Telesat said a “direct-to-consumer” model will not be its initial focus as it believes further development of low-cost terminals is necessary, but said it plans to offer service from day one that would improve network capacity for less densely populated communities through the use of data centres that would then connect to individual users using existing land-based technology.

Mr. Goldberg won’t comment on exactly how much the LEO plan will cost, but in the letter to Mr. Morneau, Telesat described the project as “a multi-billion dollar investment in capital and [research and development]."

Telesat has about $637-million in cash and generates free cash flow of between $200-million and $325-million a year, according to Michael Pace, an analyst with J.P. Morgan.

If the company’s LEO plans demand more capital than its cash and free cash flow, Mr. Pace wrote in a report last year, that “would require consideration of raising equity or [finding] a partner.”