A mining machine extracts rock at Baotou Baiyan Obo in Inner Mongolia, the world's largest mine of rare-earth minerals, in 2011. Facilities like this have helped China dominate the market for obscure but valuable elements like gadolinium, samarium and praseodymium.Reuters/Reuters

A decade ago, the future for Toronto-based Avalon Advanced Materials Inc. looked bright. Its flagship Nechalacho development project in the Northwest Territories was on track to produce rare-earth elements, crucial ingredients in a wide array of technologies from wind turbines to cruise missiles to MRI machines. Avalon’s market capitalization would eventually climb close to a billion dollars.

Today things look very different. Avalon’s value has dwindled to just $26-million, its shares trade for pennies and Nechalacho lies undeveloped.

“Unfortunately the bubble burst before we could get all the capital in place,” said Don Bubar, Avalon’s chief executive officer.

Avalon could be considered one of the lucky ones – it still exists. Many other Canadian rare-earth exploration companies did not survive. Chinese state-controlled producers have dominated the market for decades, crushing most contenders.

But amid escalating Sino-American tensions, global customers are searching for alternative sources of rare earths with a renewed sense of urgency. Last year, the U.S. government announced it was seeking allies to promote “resilient energy mineral supply chains” for a wide range of materials, including rare earths. Canada joined the effort, raising hopes that our mining industry will have a second shot at breaking Beijing’s near-monopoly.

It’s part of a much broader reconsideration by Western countries of their reliance on distant suppliers. After decades of emphasizing cost efficiency above all else, the architects of modern supply chains are now under pressure to improve their resilience to geopolitical shocks. For some, that means finding alternative suppliers in countries that are either physically closer or appear friendlier. By revealing the West’s dependence on China for N95 respirator masks, hand sanitizers, pharmaceuticals and other crucial medical supplies, the COVID-19 pandemic has further encouraged this shift.

But breaking up with China won’t be easy. The country is so embedded in global supply chains that it has become known as “the Great Assembler.” Automotive components, telecommunications equipment and power generation are just three of many fields where it has carved out formidable competitive advantages.

Merely wanting alternative sources of rare earths is not enough: Companies need to commit the huge amounts of capital to build them. Governments may need to intervene on a scale rivalling China’s own support for its priority industries. Citizens may need to pay more than they’re accustomed to, or possibly accept compromises on the environmental front.

“When I talk about our business I try not to use the word ‘mining’ because it actually misleads people into thinking these are your traditional commodities, and it’s the same old, same old. Well, it’s not. At all,” Mr. Bubar said.

“It’s been a pretty steep learning curve.”

Despite challengers,

China remains dominant

Estimated production, in thousands

of tonnes of rare earth oxide equivalents

250

Estimates exclude illegal

smuggling, and are unavail-

able for certain countries in

some years.

200

Other

Aus.

150

U.S.

100

China

50

0

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

2019

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: u.s. geological survey

Despite challengers,

China remains dominant

Estimated production, in thousands of tonnes

of rare earth oxide equivalents

250

Estimates exclude illegal

smuggling, and are

unavailable for certain

countries in some years.

200

Other

Aus.

150

U.S.

100

China

50

0

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

2019

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: u.s. geological survey

Despite challengers, China remains dominant

Estimated production, in thousands of tonnes of rare earth oxide equivalents

250

Estimates exclude illegal smuggling, and are

unavailable for certain countries in some years.

200

Other

Australia

150

U.S.

100

China

50

0

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

2019

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: u.s. geological survey

How China came to dominate rare earths

Rare earths are a group of 17 broadly similar metals with unique properties ideal for a range of high-tech applications.

They have obscure names such as praseodymium, gadolinium and dysprosium, and are mined in vanishingly small quantities compared with commodities such as copper and zinc. Yet rare earths punch far above their weight, with widespread applications in crucial military and “clean” technologies.

Samarium is used with cobalt to create magnets that work at high temperatures, making it ideal for aircraft and missile components. Erbium is used in lasers, ytterbium in fibre optics and solar panels, europium in fluorescent lighting. Rare earths are essential ingredients in mobile devices, wind turbines, electric cars, light bulbs, MRI machines, military drones.

Until the 1980s, the U.S. was the uncontested champion of rare earths thanks to a single producing mine at Mountain Pass, Calif. But during the 1990s, Chinese production surged by more than 450 per cent, relegating Mountain Pass to the slag heap.

David Abraham, a fellow at the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, a U.S. non-profit, and author of The Elements of Power, attributes China’s success to “geological good fortune, expertise at extracting resources out of the ground and making them economical, and a lack of environmental awareness or concern.”

China is richly endowed with high-grade deposits. Baotou Baiyan Obo, in Inner Mongolia, is the world’s largest rare-earth mine. Other significant mining areas are found around Ganzhou, in Jiangxi province. And even after decades of extraction, China retains the world’s largest reserves.

Substantial government support also helped enormously. According to a 2010 paper by the U.S. China Economic and Security Review Commission, many Chinese rare-earth mining companies lost money during the industry’s early years but were able to survive thanks to generous loans from state-controlled banks. This allowed Chinese rare-earth companies to produce at low prices and drive competitors out of business.

China’s competitive advantage also sprung from lax environmental oversight. “If you can blow up half a mountain or a hill, and you don’t have to worry about what’s below it, mining becomes that much cheaper,” Mr. Abraham said.

Xiang Huang, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Waterloo, witnessed the consequences first hand, in Inner Mongolia between 2011 and 2017, while studying the effect rare-earth mining had on groundwater. The concentration of rare earths in rock is usually very low. Solvents are needed to concentrate them, which is “very toxic” to groundwater, Mr. Huang said.

Air and soil pollution are even greater threats, according to Mr. Huang. Around the city of Baotou, rare-earth tailings accumulated for decades, and high winds often whipped hazardous dust throughout the surrounding region. Production “grew very quickly,” he said, but the Chinese producers “didn’t care too much about the environment.”

After 2000, the country also began consuming ever-increasing amounts of rare earths. So much so that the Chinese government introduced export quotas and duties. The global market for rare earths was tightening but not yet at a breaking point. In 2010, that changed.

In September of that year, a Chinese fishing trawler collided with two Japanese patrol boats in contested territorial waters in the East China Sea, setting off a diplomatic showdown. According to reports, Chinese exports of rare earths to Japan halted within days, prompting massive price increases. For many end users it was a final wake-up call: They were at the mercy of Chinese suppliers.

At the Separation Rapids project in Kenora, Ont., shown at top, Avalon Advanced Materials digs for lithium-rich rocks like the lepidolite shown at bottom. But it also tried to exploit new sources of rare-earth minerals, with unfortunate results.Courtesy of Avalon Advanced Materials

The dismal fates of challengers

Sensing opportunity, global investors poured substantial amounts of speculative capital into junior mining companies exploring for rare earths outside China. Soon, on paper at least, there were hundreds of potential new sources.

Canada’s Avalon Advanced Materials was well place to take advantage. It was one of the early entrants, making its move as early as 2005. “We could see then that there was going to be opportunities,” Mr. Bubar said. “Demand was growing for these rare-earth elements, yet there was really no supply source outside of China.”

With the market tightening in 2010 owing to China’s export quotas on Japan, Mr. Bubar said the company was able to ride a “flurry of interest” to raise enough capital to do a feasibility study on Nechalacho. The capital cost for the mine and processing facility was estimated at $1.5-billion. A big ask, but Avalon was optimistic it could raise the funds.

It wasn’t alone: An industry-led group called the Canadian Rare Earth Elements Network vowed in 2014 that Canada would provide one-fifth of the world’s supply of rare earths within just four years.

But the ebullience would not last.

As early as mid-2011, prices began falling as panic waned over the faceoff between China and Japan. Then, after losing a complaint by the U.S., European Union and Japan before the World Trade Organization, China abolished its quotas in 2014.

“When China relaxed the export quotas and the prices dropped, it just didn’t leave any room for anyone else to be competitive, given the large amount of capital you have to invest just to get started,” Mr. Bubar said.

The economic case for building Nechalacho had evaporated, and Avalon’s shares tanked. Seven years on, Nechalacho is no longer the company’s big focus. Avalon has been putting increased emphasis on its lithium, tin and indium projects.

Quest Rare Minerals Ltd.'s Strange Lake mine.Gareth P. Hatch

At least Avalon was able to pivot. Many others in the sector had no plan B. Montreal-based Quest Rare Minerals Ltd., owner of the Strange Lake project in the remote Nunavik region of northern Quebec, was all-in on rare-earth elements. After prices plummeted, a key investor bailed, and the company ran out of money. In 2017, Quest filed for creditor protection and shareholders were wiped out. Eventually, privately held, Montreal-based Torngat Metals Ltd. acquired its assets for pennies on the dollar.

Globally, only a handful of global rare-earth explorers actually brought mines into production. Australia’s Lynas Corp., which today bills itself as the lone significant rare-earths miner and producer outside China, only began reporting profits in 2018. U.S.-based Molycorp Inc. managed to restart California’s Mountain Pass mine, but it, too, ultimately went bankrupt.

In recent years, about 80 per cent of the United States’ imports of rare earths originated in China, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. A 2016 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the U.S. has “limited capability” to produce rare-earth oxides, metals and alloys; it could take the country 15 years to merely reduce its dependence on China.

Matt Green, mining/crushing supervisor at MP Materials, shows crushed ore at the rare-earth mine in Mountain Pass, Calif., this past January. Mountain Pass once made the United States the dominant rare-earth power until China stepped up production in the 1990s.Steve Marcus/Reuters/Reuters

Second time lucky?

In May, 2019, amid an escalating global trade war, Chinese state media warned the country might halt rare-earths exports to the U.S. The People’s Daily suggested rare earths could “become China’s counter-weapon against the unprovoked suppression of the U.S.”

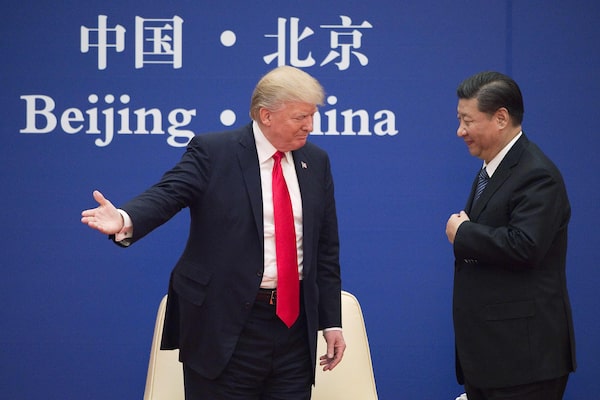

Weeks later, the U.S. State Department announced the Energy Resource Governance Initiative, intended to find new sources for critical minerals, including rare earths. The initiative was trumpeted from the highest levels: At a meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House in June, 2019, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau agreed to negotiate a joint strategy. The Canada-U.S. Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration was unveiled this past January.

Hilary Morgan directs the task force formed last fall to co-ordinate Canada’s participation. She says the team is “a whole-of-government effort” with participants from Global Affairs, Environment, Public Safety, Natural Resources and other federal departments.

Ms. Morgan said Canada already supplies 13 of the 35 minerals the U.S. government has identified as being of strategic importance (rare earths are collectively considered one of the 35). Furthermore, 13 rare-earths exploration projects are in progress in this country.

“We have very, very strong mining frameworks in Canada,” she said. “We’re investing in mining research and development, we have very strong environmental standards, we’ve got open geoscience, we’ve got a stable tax regime.

“So in terms of looking for a secure supplier, we have a lot going for us.”

Late last month, Alberta unveiled an economic recovery plan that emphasizes diversification beyond oil and gas, its largest industry. It vowed to “capitalize on Alberta’s vast mineral resource potential,” including for rare earths.

The renewed effort to break China’s rare-earths monopoly is part of a broader deglobalization process many economists predict will remake global trade flows. Stephen Roach, the former chair of Morgan Stanley Asia, wrote that “a major rupture of the U.S.-China relationship is at hand” that will prove tragic for both countries.

U.S. President Donald Trump, shown with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in 2017, has threatened to limit American trade with China.NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP via Getty Images/AFP/Getty Images

The failure of earlier attempts to dethrone China on rare earths suggest how devilishly complicated it could be to sever those relationships. It doesn’t, however, mean that the latest efforts are doomed to the same fate.

Indeed, in a report published in June, 2019, mining strategist Christopher Ecclestone of Hallgarten & Co., an economic research firm, concluded it is now inevitable that China’s production will fall to half of the global total by 2025. The reason: its ruthless squandering of a finite resource. “We are now in the territory of post-peak Chinese production of rare earths,” he wrote.

Even if this view is correct, Canadian miners must overcome extraordinary technical challenges to capitalize on that opportunity.

Janice Zinck, director of green mining innovation at CanmetMINING, an arm of Natural Resources Canada, uses a food analogy when describing the huge challenge of mining rare earths. Mining for traditional metals such as gold is akin to extracting the chips from a chocolate chip cookie, she says. The deposits (chocolate chips) are usually concentrated in specific, easily identifiable areas, and are relatively straightforward to extract.

Conversely, rare-earth minerals tend to be randomly and minutely dispersed in nature. They’re much harder to find in sufficient concentrations that make them economical to mine – like trying to extract individual grains of sugar from the same chocolate chip cookie. Making matters worse, Canada’s deposits are “harder to crack” compared with those naturally occurring in China, she says.

Rare-earth processing isn’t any easier. In the gold or copper industry, companies process ore using straightforward, efficient and stalwart techniques that are relatively idiot-proof: Mills and grinders, for example are reliable and battle-tested. Rare-earth processing facilities are infinitely more complex, and require an entirely different skill set.

Dirk Naumann, CEO of Torngat Metals – and both a physicist and chemical engineer – said that running a rare-earths facility is essentially “the chemical industry with a mine attached.”

Another challenging aspect of rare earths is they don’t trade on commodities exchanges, there isn’t a deep network of middle men who trade them and their prices aren’t transparent.

So “you can’t just sell it into any old market. You have to find buyers,” Mr. Bubar said. “That’s what’s been frustrating: Getting these supply chains established outside of China.”

Overcoming these issues will require considerable expertise. Yet it is China that possesses the critical mass of state-controlled companies, laboratories and research institutes with practical experience.

Mr. Abraham recalled attending a rare-earths conference in Lanzhou, China, in 2015, a city he said isn’t even in rare-earth mining country. He estimated about 300 people attended. “You can’t even gather 300 people in the U.S. who have expertise in rare earths,” he said.

A factory and coal-burning power plant obscure the skies over Baotou, China's biggest rare-earth mining town.DAVID GRAY/Reuters

Then there’s the environmental cost.

Historically, tighter regulatory regimes and political opposition in several countries have proved a stumbling block for China’s competitors. For example, many rare-earth elements naturally co-exist with uranium, creating additional challenges. Australia’s Lynas has suffered recurring issues related to permits at its separation plant and refinery in Malaysia, amid concerns over its importation of radioactive materials and storage of low-level radioactive waste.

China’s central government has been credited with tightening standards for its rare-earth industry, including cracking down on illegal mining and smuggling. But Hallgarten & Co. said that’s encouraged illegal mining in neighboring Myanmar.

Higher environmental standards, along with the scarcity of both high-grade deposits and talent, could price North American producers out of the market. Chinese firms could also orchestrate a price war. “They can actually drive down the price of these rare metals to the point that it’s not cost competitive elsewhere,” said Aaron Henry, senior director of natural resources and environmental policy at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

Some have suggested additional federal support for research and development. Others have recommended relieving the industry of liabilities associated with handling radioactive waste. Avalon’s Mr. Bubar believes that the U.S. and Canadian governments should commit to buying rare earths and stockpiling them.

Most of these prescriptions share a common ingredient: intensive government intervention. Put another way, to compete with China, Western countries might have to adopt some of the tactics its government applies to priority industries.

Geologists log core samples at Strange Lake when Quest Rare owned it.Courtesy of Quest Rare Minerals Ltd./Supplied

Torngat, one of the new contenders, is years away from production and must prove its novel vision for Strange Lake is feasible. Unlike Quest Rare, which had planned to extract every sellable mineral out of the rock, Torngat intends to focus only on the very concentrated deposits of rare earths. It also hopes to transport concentrates out of Strange Lake to a processing facility hundreds of kilometres south on specially designed “zeppelin” type aircraft. To do all of this, the company needs to raise about $615-million. For a junior, it’s a long shot. And Mr. Naumann isn’t counting on receiving any aid.

Last year, after the U.S. and Canada announced plans to cooperate in rare earths, Torngat executives attended many meetings with U.S. government representatives, including the Defence and Energy departments. “We filled out hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of papers but nothing happened,” Mr. Naumann said.

Meanwhile, in Canada, “the federal government, up to the PMO and the PCO, were trying to help us, but nothing came out of it.”

The harsh reality for Canada’s rare-earth players is there isn’t likely to be an easy solution any time soon. While any new government support will help the industry, many other factors need to fall in place for the landscape to change in a big way. Rare-earth prices must come back and more economical resources may need to be found. New processing technologies, that are both affordable and environmentally tenable, would be a godsend. All huge obstacles, but not insurmountable.

“We have the potential to build the value chain,” said Ms. Zinck with NRCan.

“We can’t just look at it as today, and only today, and market prices today. We need to have a longer-term view. We are getting all the pieces together to be a player and contributor in the rare-earth space.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.