During a fundraiser at Assiniboine Park's Leo Mol Sculpture Garden in Winnipeg, Sean McCoshen announced he would donate $2-million to help rejuvenate his hometown park.Phil Hossack/Winnipeg Free Press

One day before his world started falling apart, before he seemingly disappeared from public view, leaving inquiries from lawyers unanswered, Sean McCoshen had some politicians to impress. He appeared before a virtual meeting of a House of Commons transportation committee on April 29 to talk about a dream of his: building a railroad from Fort McMurray to the ports of Alaska.

It might seem quixotic, but former U.S. president Donald Trump issued a permit last year allowing the rail line to cross the border, and Alberta Premier Jason Kenney welcomed the approval. Plus, Mr. McCoshen had lined up funding to get him started. Bridging Finance Inc., a Toronto-based private lender to riskier borrowers, had put some $200-million into Mr. McCoshen’s company, Alaska-Alberta Railway Development Corp. (A2A).

He considered Bridging CEO David Sharpe to be a close friend – so close they referred to one another as “brother” when talking on the phone. They’d worked side-by-side for years. Mr. McCoshen introduced Bridging to Indigenous communities in need of financing, while Bridging made its single largest loan to A2A. The railway company has even described Mr. Sharpe as a co-founder, and he travelled with Mr. McCoshen to Washington, D.C., in 2019 to lobby officials, including former vice-president Mike Pence.

Both men pitched the railway as a transformational endeavour – a sure-fire way to get Albertan oil and other commodities to global markets, and a boon for Indigenous communities through ownership stakes. That was important to them, and the reason Mr. Sharpe, a member of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, got involved in the first place. Mr. McCoshen, while not Indigenous, has described himself as an “advocate of Canada’s Indigenous population.”

On the day he appeared before MPs, Mr. McCoshen told the committee the railway could be a model of sustainability and aspired to be the largest co-owned Indigenous infrastructure project in the world. “That is the kind of project Canada should be building right now, and we can absolutely do this,” he said.

It was the last time Mr. McCoshen has been seen or heard from publicly in nearly two months. The following day, an Ontario court put Bridging Finance into receivership, following an investigation by the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC). The regulator said it discovered numerous financial irregularities and alleged the company improperly used investor funds to benefit its founders and executives. Mr. McCoshen, a businessman from Winnipeg, has emerged as a central figure amid the fallout.

Last week, Bridging’s receiver alleged that millions of dollars slated for Mr. McCoshen’s railway company were transferred into his personal bank account. Millions more appear to have gone to a numbered company he controlled. The receiver, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC), has been “unable to determine the commercial relationship” between that company and A2A.

Money allegedly flowed the other way, too. The OSC alleges Mr. McCoshen transferred $19.5-million to Mr. Sharpe, with some of those deposits coming just days after Bridging extended loans to his companies. Under questioning by the OSC, Mr. Sharpe denied the payments were kickbacks – they were loans, he said. Neither he nor Mr. McCoshen have produced a loan agreement.

Exactly who Mr. McCoshen is and how he became so entwined in Bridging’s affairs is a pressing question for the lender’s 26,000 retail investors. He and his companies have ties to some of Bridging’s biggest and most troubled loans – more than $500-million worth, about one-quarter of the firm’s assets under management – whether as the recipient, guarantor or broker.

Bridging’s CEO has portrayed Mr. McCoshen as a savvy, jet-setting businessman. “Sean McCoshen is a person that has a lot of money and does well,” Mr. Sharpe told the OSC in April. It certainly seems that way, at first. Mr. McCoshen owns millions in real estate, rubs shoulders with billionaires, and says he has stakes in multiple companies through his firm, the McCoshen Group. According to his corporate biographies, he spent nearly two decades in finance and infrastructure development before brokering loans for First Nations.

But a Globe and Mail investigation has found Bridging has tied its fortunes – and investors’ money – to someone with a record of business failures and a vague, unverifiable résumé. One of Mr. McCoshen’s companies filed for bankruptcy, and seven years ago, he said his personal finances were “on a knife’s edge,” according to court records. As for his work with First Nations, controversy has followed him from community to community, with accusations of kickbacks and exorbitant, unexplained fees.

Mr. Sharpe did not answer a long list of questions from The Globe about his relationship with Mr. McCoshen, and instead issued a statement through his lawyer, Melissa MacKewn. “As a First Nations person, Mr. Sharpe stands by his track record of economic reconciliation in this country,” according to the statement. “Mr. Sharpe will respond to the OSC’s unfounded allegations at the appropriate time and in the proper forum, rather than arguing their merits in the media.”

Mr. McCoshen, meanwhile, has said nothing at all. He did not respond to multiple e-mails from The Globe. PwC, the receiver, has tried to question him directly, but was told by his lawyer that he’s unavailable owing to medical reasons. PwC also asked for proof that Mr. McCoshen is too ill to respond. So far, it has not received any evidence.

As Bridging’s investors await more information about the fate of their investments, the revelations about Mr. McCoshen’s tumultuous career raise serious questions about the due diligence Bridging performed before lending millions to his company, the company’s internal controls, and how closely it monitored the use of those funds. Underlying it all is just what opportunity David Sharpe saw when he got into business with Sean McCoshen – a chance to help First Nations and build infrastructure, or something else entirely.

Sean McCoshen (left), former A2A executive Robert Dove (second from left) and Bridging Finance CEO David Sharpe (right) pose with then U.S. vice-president Mike Pence after a speech he delivered at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., in fall 2019. The trio were in D.C. to lobby the Trump administration on the proposed railway.Supplied

At a glance, Mr. McCoshen is the picture of a successful entrepreneur. He travels via private jet and owns luxury properties in three countries valued at some $26-million. He has wealthy acquaintances, too, including Vancouver billionaire Francesco Aquilini. Last year, the pair helped organize a virtual fundraiser for Conservative Party Leader Erin O’Toole. A spokesperson for Mr. Aquilini confirmed the two know each other, but declined an interview.

At 53, Mr. McCoshen has a voice like a rock tumbler. He sports long, wavy hair and occasionally dresses like a monied, aging musician, with stylishly ripped jeans and a leather jacket (in his younger days, he actually did play in a Winnipeg rock band). He has a taste for higher-end brands, favouring Tom Ford and Gucci, and liked to boast about his financial acumen. During one period of his career, after a business win, he’d ask aloud, “Why am I so good?”

He was born in Nova Scotia before his family moved to Winnipeg, and he later graduated from the University of Western Ontario with a law degree. According to the various biographies that have appeared on his company websites over the years, he practised law in Winnipeg and described himself as a “securities lawyer turned investment banker.”

He’s said he worked “in conjunction with” private equity firms, participating in US$35-billion worth of financings, while another bio said he worked as managing director of an infrastructure fund. He told a business publication he once spent three years with a multinational private equity firm building a grain terminal in the United Arab Emirates. The area was home to Bedouin tribes who required extensive consultation. “It was two years of getting everybody to agree and then one year of construction, and I became very sensitized to the differences of culture,” he said.

While his bios are laudatory (“Sean is a shining example of what can be realized through intelligence, personality, determination and extremely hard work,” reads one), what’s typically missing is any detail on where, exactly, he has worked. Mr. Sharpe evidently had no doubts about his business partner’s bona fides. He told the OSC during an interview that Mr. McCoshen was a former employee of Carlyle Group, the US$260-billion global private equity company, in Washington. But a spokesperson for Carlyle said the company has no record of Mr. McCoshen ever being an employee.

That’s not the only oddity in his career. One bio states he retired from banking in 2007 after 18 years. That would mean he started in the field around 1989, at the age of 22, before he earned his law degree. As for his legal career, a spokesperson for the Law Society of Manitoba confirmed Mr. McCoshen was called to the bar in 1996, but said he never applied to commence active practice. That means he was not eligible to practise law in the province.

Unmentioned in his biographies is that he went into the fashion business and started a company called Brawd Inc. in Winnipeg about a week after he was called to the bar in 1996. An article in The Globe from the time said Brawd made “well-respected rave gear.” He also launched a line of slim-fit jeans.

Kirsten Andrews was hired to help create a lookbook for Brawd and arranged for musicians Tegan and Sara to model the clothing, but the company never paid her invoice. “It really hurt at the time,” Ms. Andrews said. Indeed, Brawd ran into money trouble. A source familiar with the company called Mr. McCoshen dedicated, but said Brawd struggled to find retail customers. It filed for bankruptcy in 2003, owing nearly $2.8-million to creditors.

Mr. McCoshen went into a completely different line of work afterward, serving as president of a Winnipeg-based company called Trans Global International Commodities Solutions Inc., founded in 2005, according to corporate records. He and a partner ran it from Winnipeg’s tallest office tower. An archived website for the company describes it as a grain exporter with “major trading partners” in Dubai. It’s unclear how successful the company was. In 2010, HSBC Bank Canada sued for $18,000 after the company allegedly failed to repay credit facilities, and its landlord later sued for unpaid rent. Trans Global did not respond to either suit in court, and it was dissolved by 2013.

Divorce records for Mr. McCoshen in Manitoba reference a company he ran with the same business partner that had at least $1.9-million in assets. Mr. McCoshen said in an affidavit the company engaged in currency trading, and his partner was “extremely bad” at it. “He lost all of the money,” Mr. McCoshen said, “and as such I have left the business.”

That was not the only misfortune to allegedly befall Mr. McCoshen. Rather than leading the cushy life of a retired investment banker, he told a Manitoba court in 2014 his personal finances were a mess. “I have a significantly negative net worth close to $500,000,” he said in an affidavit related to divorce proceedings. He was having trouble paying his legal fees and received financial support from his parents and friends. The funds were also necessary to “get my business back up and running,” he said.

By then, Mr. McCoshen operated a firm called the Usand Group that arranged custom financing deals for Indigenous communities. He was essentially a broker, tapping institutions for loans on behalf of clients and taking a commission. His first year, 2012, was an “unprecedentedly successful year,” and he earned $1.1-million before tax, he said in court filings. The windfall led Mr. McCoshen and his then spouse to buy two luxury vehicles and two houses that he said later they couldn’t afford and could only be sold at a loss. The following year, Usand was staring down $380,000 in red ink.

“Our finances are on a knife’s edge,” he wrote to his ex-wife in 2014, according to court filings. In the same paragraph, he wrote: “One thing you should know is that I am indeed a financial genius.”

Somehow, he found a way to keep Usand going. He was inspired to start the company, he’s said, after Ovide Mercredi, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, told him about the trouble many communities had getting loans from banks. Initially, he relied on Mr. Mercredi to connect him with First Nations, but the company was soon self-sufficient, he told the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples in 2015, during a hearing about infrastructure on reserves. “My phone doesn’t stop ringing these days,” he said. “I’m feeling the vibrations right now.” (Mr. Mercredi told The Globe he’s had no contact with Mr. McCoshen in four years and declined to comment further.)

While working with First Nations, he allegedly employed the same tactic the OSC would later question with respect to Bridging: kickbacks. In 2016, the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) published a story in which two First Nations chiefs said they were offered money by Usand as an incentive to sign loan agreements it had arranged. APTN posted an internal Usand document that listed the use of “kickbacks” when doing business and advised “no written record of dealings” be kept.

Both chiefs quoted by APTN stand by the claims they made about Usand. “They offered me $125,000 cash if I went with the Bank of Montreal and was successful in getting that loan,” Barry Kennedy, former chief of Carry the Kettle First Nation in Saskatchewan, told The Globe recently. He said he rejected the offer. The other former chief, Morris Shannacappo of Rolling River First Nation in Manitoba, also stands by his claim that Usand offered him money to accept a loan, which he turned down.

After APTN’s reporting, Mr. McCoshen filed a $35-million defamation suit against the reporter and both chiefs, alleging they worked together to harm his reputation by publishing false claims. (APTN declined to comment, saying the case is before the courts.) Usand denied paying “sponsorships” to individuals. Instead, the company would give back to a community by sharing a portion of its fees “to sponsor appropriate, broad-based community initiatives that were supported by Band council.”

The suit also attacked the credibility of the chiefs, claiming they had a history of making unsubstantiated allegations for personal gain. (Mr. Kennedy said he finds the accusation insulting.)

The chiefs’ allegations seemingly did little to slow Mr. McCoshen down. Nor did it deter David Sharpe and Bridging Finance from working with him. It’s not entirely clear when and how the two met, but Mr. Sharpe told the OSC they first encountered each other a few years ago through their involvement with First Nations. Mr. McCoshen, in turn, called him a friend in a 2015 affidavit in divorce proceedings.

One of their early deals involved a $10.8-million loan from a Bridging fund to Misipawistik Cree Nation in Manitoba. Usand took nearly $570,000 in commissions for arranging the 2016 transaction.

Misipawistik needed the money to build houses, which Mr. McCoshen would provide through a joint venture with renowned Indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal, who designed the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa. They used a design of Mr. Cardinal’s that employed sustainable materials to reduce mould growth, a problem on many reserves. (Mr. Cardinal did not respond to requests for comment.)

The project to build 30 homes went awry, according to a lawsuit Misipawistik filed last year against Mr. McCoshen and his companies. The joint housing venture, dubbed Douglas Cardinal Housing Corp., began constructing five homes, but none were completed. Usand, which dealt directly with builders on behalf of Misipawistik, hired a new contractor. The lawsuit alleges Usand delayed paying the company, leading it to stop working and then quit entirely. Usand hired a third company, First Nation Builders and Supplier (FNBS), which completed 20 houses. Even so, Misipawistik alleged Usand again delayed payment, resulting in more work stoppages.

Trevor Charrier, owner of FNBS, said he visited Usand’s office in Winnipeg multiple times trying to get paid. “There’s like 20 desks all set up, and nobody would be in there,” he told The Globe. Eventually, he had to text Mr. Sharpe. “If I don’t receive final payment I will be in no position to keep going,” he wrote. “I am a small company and can not take a hit of 180K.”

Because of the delays in Misipawistik, Mr. McCoshen renegotiated the community’s funding arrangement multiple times – the amount grew to $15.9-million – and took a commission for each new deal, according to court documents. The lawsuit alleged Mr. McCoshen negligently or intentionally created delays to increase the loan and his own commissions. Ten houses were not built because the community had no money left.

Misipawistik said it was saddled with an additional $2.4-million in expenses and needed another $3.1-million to build the remaining houses. The band switched lenders in 2019 and cut ties with Usand. Misipawistik dropped the lawsuit a few months after filing it and declined to comment.

Despite the tumult described in the lawsuit, the First Nation is still listed on the website for Mr. McCoshen’s company, which notes it “worked together” with community members and sourced millions of dollars “to build almost 50 homes.”

From left to right: Sean McCoshen; Bridging Finance then-CEO David Sharpe, renowned architect Douglas Cardinal and a Bridging VP in Ottawa for the launch of a company dedicated to building sustainable housing in First Nations communities.Twitter

A few years ago, an apparent whistle-blower went to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) with grave concerns about Peguis First Nation, the largest such community in Manitoba. The concerns included a number of allegations about business deals the First Nation had made, including that Mr. McCoshen’s company paid kickbacks to certain band members and representatives.

The department commissioned Deloitte to investigate, which sent its findings in a confidential report to INAC in 2018. Deloitte did not identify “information to support or refute the payment of kickbacks by Usand” to anyone in Peguis, according to a copy reviewed by The Globe, but the investigation was limited because Deloitte couldn’t access crucial documents, and key individuals declined to be interviewed, including Mr. McCoshen. The report, however, details questionable transactions he was involved in.

He first came to the reserve in 2012 and struck a deal with Peguis to move its accounts from Royal Bank of Canada to the Bank of Montreal, while taking on additional financing. Deloitte could not determine why Peguis did so.

The next year, he formed a new company that was jointly owned by Usand and a local Peguis business development firm. Peguis instructed Mr. McCoshen’s new entity to help find $22-million for a land deal the community was pursuing. In the end, Peguis secured the funds from its own trust (which contained money from a land-claim settlement with the federal government) and not an outside bank. Mr. McCoshen’s company invoiced Peguis for helping broker the deal and was paid $935,000, but Deloitte found no evidence it played a role. “The question arises as to why any financing fees would be paid” to the company, according to the report.

His fees for other services drew concern, too. Around the same time, Peguis retained Usand for three months and directed it to secure financing. Usand obtained $29-million from BMO, but its engagement with Peguis stretched to 15 months. Each month, it received a $15,000 work fee.

Some Peguis representatives pushed Mr. McCoshen to justify why Usand should continue to be paid. When one official questioned him over e-mail, Mr. McCoshen forwarded the message to another band member, writing, “[Expletive] hate this idiot.” He threatened to sue the community and withheld the funding until he was paid his fee of close to $1.2-million.

Later that year, Peguis appeared to pay Usand in full, though Deloitte noted it could not obtain supporting information documenting the payments. The company’s monthly fee was supposed to be deducted from the final amount, but it does not appear that happened. Usand was possibly overpaid by $225,000, according to Deloitte.

He only deepened his relationship with Peguis in the following years – and brought in Bridging Finance, too. When Peguis faced a housing shortage and a lack of job opportunities in 2017, it turned to Mr. McCoshen to find money for economic development, and he arranged a $30-million loan from Bridging. But Peguis already had a loan from BMO, and it was not supposed to take on more debt without advising the bank. The Bridging loan put Peguis in breach of its covenant, and BMO demanded repayment.

Peguis was forced to find $30.4-million in 30 days, according to a report from Chief Peguis Investment Corp. (CPIC), which manages investments on behalf of the community. Mr. McCoshen was again there to assist. He brokered another Bridging loan with a high interest rate – more than 11 per cent, compared with about 4.7 per cent from BMO. CPIC says Usand was paid more than $7.2-million in fees for brokering deals for Peguis.

The community is now heavily indebted, with more than $122-million owed to Bridging as of March, 2020, according to Peguis’s financial statements. The relationship has soured, too. In May, council sent a letter to band members claiming Bridging refused to advance funds for a new seniors’ centre and a gas station. “Chief and Council realized that [Bridging] had no interest in the advancement of the community or the direct needs of our people,” the letter reads.

Council retained band member and former senator Murray Sinclair to review the transactions with Bridging earlier this year, before it was placed into receivership. “The amount of interest that [Bridging] was charging Peguis was phenomenal,” he told The Globe in an interview. “The concern I had was that it is conceivable that Peguis was taken advantage of.”

Alan Park, the CEO of CPIC, has a different view of where blame lies for Peguis’s financial woes. Bridging, he said, came to the rescue when BMO called its loan. A good portion of the fault should fall on Mr. McCoshen, who earned fees every time he brokered Peguis’s debt, starting with the original BMO loan, then the Bridging loan that put Peguis in breach, and finally another Bridging loan to pay out BMO, he said.

The vast majority of Indigenous community borrowers are honourable and reliable clients, he added. But when loans go bad, he said, the cause can usually be traced to one thing: band councils who are “led astray by advisers who have no skin in the game, other than a quick cash grab, tell the community what they want to hear and leave town in a Lamborghini to the airport to get on their private jet.”

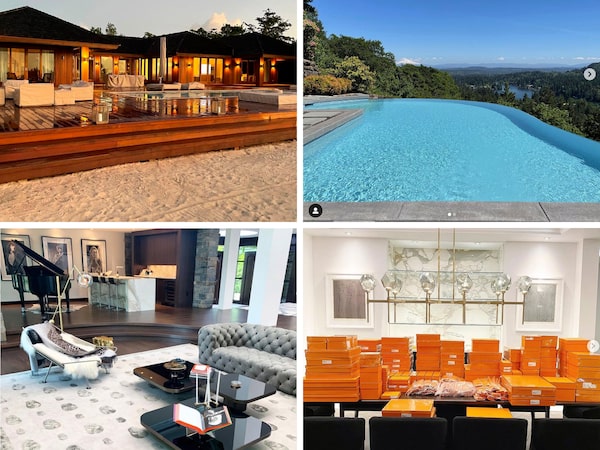

Sean McCoshen amassed a pricey portfolio of luxury homes, several photos of which were posted on Instagram by his interior designer. Clockwise from top left: his beachside home in Turks and Caicos, which he bought in 2019 and is now up for sale; his mansion in Lake Oswego, Ore., featuring a zero-edge pool; Mr. McCoshen’s supply of Hermès China for his Lake Oswego home; and his house in Winnipeg, which the designer injected with a “rock-star vibe,” complete with rare photos of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brigitte Bardot. Mr. McCoshen sold the house in 2020.Instagram

As Mr. McCoshen has spent more time on the A2A railway project in recent years, his personal assets have ballooned. Between 2019 and 2021, he splurged on multimillion-dollar properties in Vancouver, a vacation pad in Turks and Caicos, and a 7,700-square-foot mansion in Lake Oswego, Ore. In Los Angeles, he sublet a home described in real estate listings as an “entertainer’s paradise” for $32,500 a month, according to legal documents.

To outfit his abodes, he hired a Vancouver-based interior designer whose Instagram page is a testament to his expensive tastes: a marble steam shower, an infinity pool overlooking an Oregon mountain range and a Seiler grand piano atop a zebra-print rug. (“If the client doesn’t play but they have the space, I still put in the grand piano,” the caption reads.)

For Mr. McCoshen, it seems like a remarkable reversal of fortunes, considering just a few years earlier, he was struggling to get his finances together. His main project, A2A, does not yet have revenue, either. How he turned his finances around – and where all the money came from – isn’t clear.

His real estate spending spree happened after Bridging Finance started advancing millions of dollars to A2A, and some of the loan transfers from Bridging to A2A appear “to be outside of the normal course of business,” PwC, Bridging’s receiver, alleged in a recent report. In total, PwC found a dozen transfers of Bridging funds as part of the A2A loan since 2015. About $83-million went to a numbered company Mr. McCoshen controlled, and PwC could not determine the commercial relationship between it and A2A. Another $25.5-million went to one of Mr. McCoshen’s personal bank accounts last year.

The numbered company is the same one the OSC alleges he used to transfer $19.5-million to Mr. Sharpe between 2016 and 2019. Some of the payments arrived in Mr. Sharpe’s bank account within days of Bridging advancing loan funds, according to the OSC. While Mr. Sharpe denied the payments were kickbacks and said they were loans for him to make personal investments, he acknowledged the optics. “It certainly does not look good,” he told the OSC. “That’s for sure.”

A2A is also an unusual investment for Bridging, which has long marketed its specialty in short-term lending. In addition, Bridging tends to charge high interest rates to compensate for the risky nature of its borrowers, but A2A does not pay interest in cash; its interest charges are instead added to the total value of the loan, to be repaid only at maturity. The company now owes about $208-million to Bridging, which also has an equity stake in A2A that it values at $109-million.

Despite the large sums transferred to A2A, a source familiar with its operations said its largest expenses were engineering consulting fees and legal bills, and these costs did not come close to $200-million. PwC demanded repayment of the funds from the company and from Mr. McCoshen, who guaranteed the loan. A2A told the receiver it only has $1-million in cash on hand after making other priority payments.

The OSC has inquired about Mr. McCoshen’s ability to backstop such a sizeable debt. Mr. Sharpe told the regulator the permits already obtained by A2A, including one issued by Mr. Trump, held a lot of value. Bridging also submitted a net-worth statement to the OSC valuing Mr. McCoshen at $3.9-billion – but nearly the entire amount is attributed to A2A, based on an estimate prepared by consulting firm McKinsey and Co. Built into that number is the large assumption, in the OSC’s view, that governments will contribute billions to the project. After removing the railway company, the OSC said Mr. McCoshen’s net worth is negative $96-million.

Since Bridging was placed in receivership, A2A has been hit with departures. Last year, J.P. Gladu, former head of the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, signed on as president and worked to engage Indigenous communities. He appeared with Mr. McCoshen in front of the House of Commons transportation committee back in April. “It has been an absolute pleasure to be working on this project with Sean,” Mr. Gladu said. “His passion for this work is palpable.”

On June 2, he sent in his resignation letter. “The events over the past month concerning Bridging Finance Inc. have significantly compromised the vision of A2A Rail and put the project’s future in immediate peril,” he wrote in the letter, obtained by The Globe. “The uncertainty emerging out of recent events have undermined the carefully constructed relationships I have worked hard to build with the Indigenous peoples and governments of the Canadian Northwest.”

Mr. McCoshen can no longer count on Mr. Sharpe either, as he was removed from his CEO post at Bridging immediately after PwC took control. In the previous few months, Mr. McCoshen was evidently on his mind. More than once last year, Mr. Sharpe and another Bridging executive asked an employee to go to the office and perform searches for e-mails to delete, according to PwC. In total, 34,000 e-mails were wiped from Bridging’s server.

Among the search terms was “Sean McCoshen.”