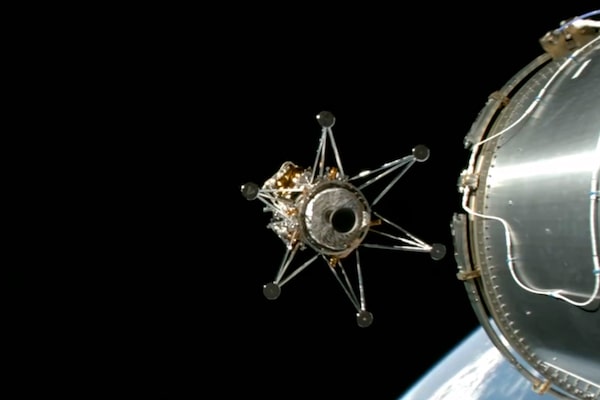

Intuitive Machines' lunar lander Odysseus separates from a SpaceX rocket's upper stage before heading toward the moon on Feb. 15.The Associated Press

It took 10 years for Odysseus to complete his epic voyage from the Trojan war to his home on Ithaca.

For the lunar lander named after Homer’s mythical seafarer, a mere six days is enough to get from Earth to the moon. But now comes the real peril as the 1,900-kilogram uncrewed vehicle, developed by Intuitive Machines Inc. of Houston, tries to become the first commercially built spacecraft to safely touch down on the moon’s surface.

If the mechanical version of Odysseus succeeds at the attempt, expected no sooner than 5:49 p.m. ET on Thursday, it will mark a new chapter in commercial space exploration. It will also signal the long-awaited return to the moon for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which has several payloads aboard the lander. The U.S. space agency has not had a presence on the lunar surface since the final Apollo mission concluded in 1972.

Canadian know-how is also represented on Odysseus, with seven systems and components provided by Canadensys Aerospace Corporation of Bolton, Ont. While the company has an established track record in space, Odysseus represents its largest involvement to date in the race to commercialize lunar exploration.

“Our centre of expertise is exploration missions and there’s a big emphasis on lunar surface activities right now,” said the company’s president, Christian Sallaberger.

If all goes well, the lander will set down on a smooth patch of lunar topography near the crater Malapert A, about 300 kilometres from the moon’s south pole. The area is considered ripe for scientific investigation because of the possible presence of lunar ice in permanently shadowed craters in the region. Artemis III, NASA’s first crewed mission to the lunar surface since the Apollo era, is similarly aiming for a landing somewhere near the south pole when it sets out for the moon in 2026.

Odysseus was launched on a Space X rocket from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center on Feb. 15 and has had an uneventful trip so far. On Wednesday morning, Intuitive Machines announced the spacecraft has entered lunar orbit on a circular trajectory about 92 kilometres above the moon’s crater-scarred surface.

In doing so, it has already achieved more than the first U.S. commercial lander sent to the moon. Dubbed Peregrine, that device was built by Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic Technology and launched on Jan. 8. However, the mission went awry a few hours after liftoff because of problems with the spacecraft’s propulsion system. Peregrine never left Earth’s orbit and was destroyed 10 days later in a controlled re-entry.

Both Odysseus and Peregrine are part of a NASA initiative known as Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS. Its ultimate goal is to hand off the task of ferrying material to the moon to the private sector. A similar effort involving flights to low Earth orbit was started in 2006 and opened the door to Space X and other private companies becoming the primary means of getting people and supplies to the International Space Station.

Christian Sallaberger, president and CEO of Canadensys Aerospace, stands inside the company's lunar test environment in Stratford, Ont. on Aug. 15, 2022.Patrick Dell/The Globe and Mail

As part of CLPS, Odysseus is meant to help create a more robust and routine pathway to the lunar surface. This will aid the science that is needed to support the Artemis program but could also end up serving customers that are willing to pay for access to the moon. Along the way, the program’s leaders hope the effort will draw the moon firmly into the sphere of activity that comprises today’s space economy.

“With a commercial industry comes a competitive environment,” said Sue Lederer, NASA’s CLPS project scientist for the Odysseus mission, during a teleconference with reporters last week. “Being risk tolerant allows for high yield and high reward.”

Certainly the risk side of the equation will be front and centre during Odysseus’s descent to the moon.

Since 1966, four countries, the Soviet Union, the United States, China and India, have successfully soft-landed machines onto the lunar surface. On Jan. 19, Japan became the fifth with the caveat that its SLIM lander is thought to have rolled down a slope, ending up in an upside-down position.

That and other recent mishaps underscore how challenging the moon remains. So far, landing on the surface is a goal that has eluded every privately funded effort or company that has tried.

But each failure adds to a growing expectation that at some point, someone will succeed.

“We’re all cheering for all the missions,” said Dr. Sallaberger, whose company has worked with a number of lunar lander teams, including the one that built Japan’s upside-down craft. “The lessons learned by one also benefit others.”

In total, he said, Canadensys has worked with three customers to provide various elements for the Odysseus payload.

One that is particularly groundbreaking is a telescope built in Canada as a proof-of-concept test for the International Lunar Observatory Association, a Hawaii-based organization that aims to turn the moon into a remote, airless platform for astronomical studies of the distant universe.

If it survives Thursday’s landing intact, the telescope carried on board Odysseus will attempt to take the first images of the Milky Way’s galactic centre as seen from the moon.

While the view may not compare to the dazzling releases lately seen from the James Webb Space Telescope, the project’s aim is to see whether the moon can play host to many more telescopes that can perform large-scale surveys that Webb and other space observatories would never have the time to conduct on their own.

As Homer might say, it is a quest worthy of the gods.

Inside a nondescript industrial building in Stratford, Ont. is a small part of the moon — simulated, of course. Using sand and gravel with a low-slung light, engineers at Canadensys Aerospace test how their small prototype moon rover handles rough lunar-like terrain.

The Globe and Mail