Emergence casts the company as a swarm of insects responding to their natural environment.Bruce Zinger

The National Ballet's Made in Canada program, which opened in Toronto on Wednesday night, is a homegrown event in two senses. Not only are we getting three ballets by three Canadian choreographers – James Kudelka's The Four Seasons (1997), Crystal Pite's Emergence (2009) and Robert Binet's The Dreamers Ever Leave You (2016) – but each work was also made on the National Ballet itself, giving us a panoramic view of the company across three decades.

Crystal Pite's entrancing Emergence, the final work of the evening, was her first commission for a major ballet company. It's a piece that feels as smart as it is visually thrilling, and reveals the seeds of ideas on which she has since built in commissions at the Paris Opera Ballet and London's Royal Ballet. We see the sensitivity she can extract from an individual body and the magic she can wreak from the cumulative effect of the corps.

Set to an electronic score by Owen Belton, Emergence casts the company as a swarm of insects responding to their natural environment. It brilliantly interrogates the overlap between crowd instinct and individual agency – a clever double-entendre with the idea of the corps de ballet, which prizes order and uniformity. Watching it, I had a feeling I typically have when watching Pite's work, the sense of being in the confident hands of a choreographer who knows exactly what she's trying to achieve and makes accordingly specific choices. These choices go right down to the lighting: The ballet begins with a pas de deux that casts Sonia Rodriguez's arms in shadow. They point and bend with a bug-like ungainliness, until she's airborne in a symbiotic pairing with Ben Rudisin. The duet has them contracting into each other's bodies to suggest a synergetic co-dependency.

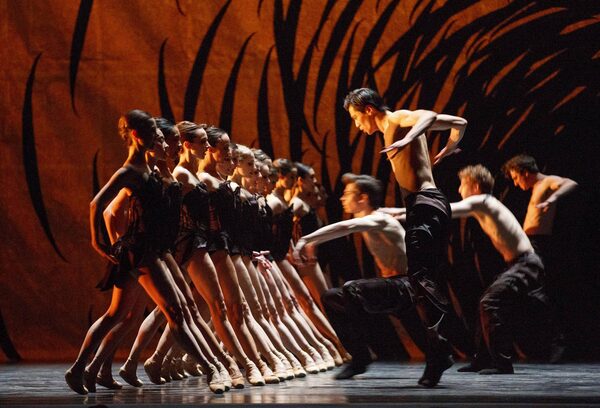

Pite typically likes to subvert the rigid gendering of classical ballet; here, she plays into it with intelligent self-consciousness. When the corps emerges from a bright sphere at the centre of the hive (Jay Gower Taylor has painted the backdrop with an orb of black lines that intensify at the centre), the dancers are delineated by gender. The women are dressed in angular leotards and wield their pointe shoes like long, hooked claws, while the men are bare-chested and move with a slinking muscularity that keeps them closer to the ground.

In a riveting sequence, the women form a long vertical line, repelling the men as they traverse the stage while throwing their classical tendus off-kilter. At another point, Pite has the women counting aloud, suggesting the automation of swarm behaviour, while gesturing, self-reflexively, to the counting of beats and steps in ballet itself. Then, with absolute confidence, Pite destabilizes the established gender binary by sending principal dancer Heather Ogden on stage as the fourth member of a group of men. Ogden blew me away in this sequence, devouring space with a grounded strength that seemed to transcend any notion of gender.

Kudelka's Four Seasons, set to Vivaldi's eponymous concertos, follows a man (Guillaume Côté) through four phases of life: youth, prime, middle age and old age. The ballet is a beautiful, semi-narrative structuring of Vivaldi's evocative score, and uses a ballerina to personify each season. Standout sequences include the Summer pas de deux, in which Greta Hodgkinson embodies both the sensuality and maturity of a romance in the prime of life, an idea that's contrasted by an exuberant corps bounding into high arabesques and grand jetés. Winter begins with a haunting sequence that has Côté shadowed by his former self (Robert Stephen), whom he repeatedly tries to toss off stage. Both men wear trench coats that balloon in the air as they move, as though suspended in their own memories.

After Binet's The Dreamers Ever Leave You premiered at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2016, I named it one of my favourite dance works of the year. An immersive ballet, in which disparate scenarios unfolded simultaneously on three stages, its essential characteristic was the space it shared with its audience, who were free to roam around the dancers and could observe the charged, spiritual choreography up close. Inspired loosely by the paintings of Lawren Harris (the ballet ran in conjunction with the AGO's Harris exhibition The Idea of North), the ballet's magic derived from the sense of being air-dropped into one of these cool, Arctic landscapes, and the attendant thrills of liveness and haphazardness.

The work was never intended to be presented on a proscenium stage; I'm not sure why artistic director Karen Kain thought this was a good idea. The choreography wasn't built to be seen at a distance; by design, it doesn't engage with space, stage-picture or continuous duration in a traditional way. Without a total conceptual rethinking of how the choreography could work as a single take, the ballet looks unstructured and lacks a dramatic arc. The aesthetics of light and sound are still lovely – Lubomyr Melnyk's live piano accompaniment is a consistent pleasure – but this Dreamers feels as though it's yearning to return home.

Made in Canada continues until March 4 (national.ballet.ca).