"Asleep or awake, working or eating, indoors or out of doors, in the bath or in bed – no escape. Nothing was your own except the few cubic centimetres inside your skull." And even that tiny space was under attack by Big Brother, as Winston Smith, the hapless hero of George Orwell's 1984, soon discovered.

Are there not entire days when the torrent of tweets from Donald Trump feels similarly inescapable? Trump has 26.9 million followers on his personal Twitter feed. Another 16.2 million people attend the official presidential Twitter spigot. He can divert an entire nation's attention from, say, the possible collusion of his campaign managers with Russian hackers, to, say, the false accusation that Barack Obama tapped Trump's New York phone line. He even has his own language and spelling, whose purpose is "not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees … but to make all other modes of thought impossible." Oh, wait, sorry, that's Newspeak, from 1984, not Trumpian Tweetspeak. But you see the similarity.

The question is, how do you take shelter from that barrage? Is it possible? Is it necessary? What is the antidote to Trumpanyl, the hour or two or even three an otherwise level-headed citizen (I'm not mentioning any names) can spend on a given day absorbing the President's latest tweeted provocations, and the bottomless online arguments they spawn?

Certainly one ought to stay engaged and fight for the version of democracy one favours – presumably that accounts for the vast majority of people who read Trump's tweets, whether they support him or hate him. But even if you try not to get upset by those tweets – because a response is what he craves, so he can display the rudest and most roaring ripostes to his base of believers and say "See? This is why we must have a more authoritarian state!" – even then, repressing the desire to respond to a provocation (as Freud noted in an entirely different, i.e. sexual, context) is as exhausting as the provocation itself. In which case, Trump wins again, by rendering his opponents weary of engagement. Donald the Trickster has hijacked the collective consciousness of the world, on both sides of the political spectrum. How the hell did we let that happen?

I've encountered a few alternatives to thinking about President Trump, but they haven't lasted. A fortnight ago I hung a new painting of Kinbasket Lake, in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, at the top of my stairs. It was by an artist named John Hartman. Every time I see the picture, I feel relieved, opened up almost to the point of tears: Here is someone trying to see the 500-million-year-old world in an unexpected way, as something other than an endless chain of daunting fears, as Trump claims to.

But I don't spend a lot of time cresting the second-floor landing of my house, so the painting's balm is not always available. Trump, by contrast, is everywhere, on every feed and every channel and every device, in the newspaper and on the screen, even on the agenda (by all reports) at AA meetings and in analysts' offices. He turns up in every crevice of modern life, like aggressive lint.

Then, a couple of weekends past, at a friend's ski cabin north of Toronto, at the back of a London Review of Books lying unopened on a coffee table, I found an excerpt from the 2016 diary of Alan Bennett, the English playwright. Bennett's 82 now, but his spirited scavenging from his life yanked my spirits above the Trumpline for a day and a half. Bennett noted the heavy toll 2016 took on his colleagues in the entertainment business (David Bowie, Alan Rickman, Edward Albee), his fear that the Last Judgment, when it finally arrives, will resemble the cheesy BAFTA Awards, his garden's progress, his despair over Brexit (which he likened to the crisis in Munich in 1938), a long-awaited trip to Venice ("surely for what will be the last time"), as well as his loathing for Trump (a "lying and bellicose vulgarian").

As somber as Bennett's year often was, his entries were never belligerent, never misspelled or misspoken. They never insisted on their own pre-eminence, and were not intended to demoralize his opponents, as Trump's are. They were the modest, private observations of a modest, private, individual consciousness, offered to a possible individual reader's passing attention. Reading Alan Bennett was like coming out of a tunnel. Reading Donald Trump is like heading into one.

But Bennett's diaries are a limited resource: I was back up to sucking three hours a day of Trump in no time.

Then I received an e-mail from my old friend Ian Paterson.

Paterson was originally from Brantford, Ont. We were at university together: I have always called him by his last name. He was a scratch golfer, and might have made it on the Tour, but chose instead to study art, and to be an artist in Paris. In the stretches when he hasn't been making art, he has developed a decades-long obsession with Samuel Beckett and his most famous play, Waiting for Godot.

It's a common enough obsession. Waiting for Godot is the play everyone studies in high school, in which Vladimir and Estragon, two rootless tramps in bowler hats, pass time by making plans to leave (they never do) as they wait at a country crossroads for Godot, a man who never arrives. They are visited briefly by a fat bully with a whip (Pozzo) and his babbling skinny servant (Lucky), and then a boy, who promises Godot is on his way. In Act II, the same things happen all over again, the only difference being that Pozzo has become blind and is now dependent on Lucky. Godot never arrives, again, and Vladimir and Estragon fail to leave the crossroads, again.

Waiting for Godot has been called "the most significant English-language play of the 20th century" and also "the only play in which nothing happens, twice." Scholars and critics have been arguing about what the play means, if it means anything, and especially who Godot is and what he is supposed to represent, since it was first produced in Paris in 1953.

There's the popular religious interpretation (Godot is God, unavailable to help faithless modern man), the psychological interpretation (Vladimir is the id, Estragon is the ego), the historico-political interpretation (the hapless French gents await the Nazi bully Pozzo), the philosophical interpretation (Godot is death, and never arrives until it's over), to list a handful. Samuel Beckett, the knife-faced Irishman who wrote the play in French and then translated it into English, refused to confirm any single interpretation. "If by Godot I had meant God I would have said God, and not Godot," he once told Ralph Richardson, who, as a result of Beckett's non-explanation, turned down the chance to play Estragon in the 1955 English-language premiere of the play – which Richardson, reproaching himself later, considered "the greatest play of my generation." Beckett claimed he didn't know who Godot was, and didn't want to know.

Against this welter of theory and postulation known as the Beckett industry, Paterson had written and illustrated a 120-page book about the play – in which he claimed not only to have figured out how the play works, and what it's about, but to have found Godot, to boot.

He sent the book to publishers, trying to get it into print, to no avail, and eventually issued it himself, as Searching for Godot, on Amazon. After reading his e-mail, I immediately looked it up. It wasn't clear that anyone had ever bought a copy; certainly no one had reviewed it. (Paterson admitted he had been upset by this lack of response when he first released it in 2015, especially the total silence from Beckett scholars, who will read anything about their eccentric hero. On the other hand, Paterson considered such anonymity par for the course in a creative career: No artist knows if his or her latest obsession will yield anything of value. "I think that's ongoing," he once told me. "It's constant, this crisis." It made complete sense to me that an artist, someone who had devoted his working life to uncertainty of making art, would be drawn to a play about the precariousness of human existence. In a way, the play is the perfect foil to the age of Donald: The president never doubts that what he feels and thinks and therefore blurts is of anything but supreme importance.)

Eager to stave off my Trump addiction, I read Paterson's book quickly, and called him up. He lives on the southeastern outskirts of Paris now, on the verge of the forest of Fontainebleau; he has to underpin the fence around his property to keep wild boars from ruining his garden. He sounded glad to hear from me. The previous Saturday, coming out of the Church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris (Paterson teaches drawing at the Paris College of Art, and the church is famous for its Delacroix murals), he had almost tripped over a dog. "Which turned out to be attached to Catherine Deneuve," Paterson said.

"What did you do?" I asked "I said ' Bonjour, Madame!'" He paused. He's a very courtly guy, Paterson, and the encounter had made him thoughtful. "Being face-to-face with Catherine Deneuve is not the same as seeing her on the screen." He seemed upset, almost ashamed, to have noticed such a thing.

Then he started talking about Waiting for Godot, a play about the potential pointlessness of human existence. To my surprise, our conversation was at least as engaging as President Trump's tweets – even the ones about Nordstrom's evil treatment of his daughter Ivanka.

Paterson's high-school English class read Waiting for Godot aloud in the mid-1970s; Mr. Morrison, his teacher, assigned Ian the role of Godot, a joke Paterson didn't get until the end of the play.

By 1984, 10 years later, Paterson had moved to Paris to be a print-maker. As Beckett and the American painter Cy Twombly (another one of his heroes) were before him, Paterson is a modernist: He never wants to repeat what other artists have done before, technically speaking, even if his subject matter remains eternally and unfixably human. Paterson made his first etchings as a print-maker – one already rejecting conventional ideas of what's supposed to be "artistic" – by rubbing copper plates up against the statues and stones in various art-strewn public gardens in Paris, and printing the results.

He then moved on to making pinhole photographs – that is, scenes projected (thanks to the natural physics of light) onto light-sensitive paper through a tiny opening in a lightproof box. These were more conventional images, but created with a lot of difficulty and the most rudimentary technology. (Paterson has since abandoned photography because of the ubiquity of the phone camera, and has taken up painting again.)

One day, while Paterson was exposing a pinhole scene in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris, Samuel Beckett walked through the frame. Beckett lived nearby. Because pinhole photographs have long exposure times, the playwright never showed up in the negative – just as Paterson, despite playing Godot, never appeared in his high-school play. Paterson took the invisible encounter as a sign. "I realized no one had figured out who Godot was," he said over the phone. "I thought, if Beckett was a real man, then maybe Godot was a real person."

He began to read everything he could find about Beckett and his famous play. He saw the playwright twice more on the streets of Paris, but was too shy to introduce himself. In the course of their closest encounter, a young girl happened to run between them as Beckett passed Paterson, forcing the playwright to bump into the artist. Paterson almost spoke, but decided against it. "From the look in his eye," Paterson remembers, "you could just tell there was no way. It just said, 'Don't bother.'"

Instead, Paterson spoke to anyone he could find who had ever met Beckett in person, including Jean Martin, who played the servant Lucky in that first production of En Attendant Godot, at Paris's Théâtre de Babylone.

"And they all said different things about him. I didn't learn very much," Paterson said matter-of-factly. What he did learn was that Beckett disliked being asked who or what Godot was. "Beckett would get quite mad. On the other hand, he was adamantly strict about certain details. At one point in the play, for instance, Estragon's pants have to fall down. And they have to fall down completely. Beckett was adamant about that." When Jean Martin asked for guidance on how to play Lucky, who babbles his long and wandering stream of a speech in a barely interrupted blurt, Beckett asked the actor if he had ever seen someone with Parkinson's disease. Martin had not, and neither had Beckett, so together playwright and actor went in search of such a person. Something must have clicked: Martin's initial performance as the increasingly shaky Lucky was famous for making audience members vomit.

But it was the text of the play that grabbed Paterson's imagination hardest. He read it obsessively. Incessant wordplay hops back and forth between English and French. In the French title, for example, the word attendant translates as "waiting" – also as, to expect something to happen, to lie in wait, even (morally) to lie while waiting. An attendant is one who waits – like Vladimir and Estragon, the hapless main characters in the play. Lucky, on the other hand, who shows up with logorrhea, is an actual waiter – he serves Pozzo. And the boy in the play, who arrives with a message from Godot – le garçon? Garçon! Check, please! Another waiter.

But Paterson noticed an entirely new sub-basement of verbal byplay as well. He made lists of words that turned up again and again in the text, resonating mysteriously: tree, nothing, game, late, last, bones. There were dozens of them, suggesting a multiplicity of meanings. One day, crossing the Seine over the Pont Neuf, Paterson noticed the flags of the Parisian department store Samaritaine. In the next instant, he recalled one of Pozzo's lines from the English translation of the play: "Add them to my store." It was then that Paterson had a revelation: "I thought, my God, it's all about his name." The play was a play – "on his, Samuel Beckett's, name."

Paterson had come up with a radically original interpretation of a play that has been studied to death and back by scholars and obsessives for 65 years: Every significant textual interaction in the play can be traced back, via a string of puns and double meanings and retro associations, to two words alone: Samuel Beckett, the author's name. "The more I got into it," Paterson told me over the phone, "the more I was sure no one else had understood it."

That's not surprising. You have to read and then reread Searching for Godot (written, at times, in a Joycean style, and illustrated with Paterson's pen-and-ink sketches of characters and bicycle wheels and wandering streams – of consciousness, get it?) to begin to grasp his interpretation. Why, for example, do Estragon and Vladimir claim to like wordplay? "Pour s'amuser," to amuse themselves – and for Sam to amuse himself (s'amuser). Are you starting to get the picture? Vladimir and Estragon suffer from endless ailments that appear and disappear – psycho-Sam-atic afflictions. Many scholars believe the word Godot (pronunciation on the first syllable, please) refers to the slang French word for boot, godillot or godasse: the play opens with Estragon struggling to pull off his boot.

But as Paterson points out, un godet is a little bucket, and un godot is a maker of little buckets. In that case Sam-Well [Samuel] Bucket [Beckett] is un godot – a man who makes his own name over and over again. And of course Samuel, in Hebrew (Beckett loved dictionaries and lexicons in all languages) means "name of God." If, in the beginning, there was the Word, and the Word was God, Samuel (Beckett) is the maker of this universe, creating the language of an entire play not from reality, not from human consciousness, not even from mere language – that had all been done before by others, including James Joyce, for whom Beckett worked as a secretary/researcher on Finnegans Wake. Instead, Beckett doubles down, and creates a dramatic universe from his name alone. Cogito, in other words, ergo Sam.

It's a far-out theory, but completely in keeping with the way Beckett understood the lifelong project of his writing. "I realized that Joyce had gone as far as one could in the direction of knowing more, [being] in control of one's material," Beckett once observed. "He [Joyce] was always adding to it; you only have to look at his proofs to see that. I realized that my own way was in impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away, in subtracting rather than in adding." (The more information Trump gives us – sorry, can't help myself! – the less we know for certain, though that's not what Beckett meant.) But having worked out an original theory regarding Beckett's intentions – a significant accomplishment – Paterson still found his book unfinished. A book of words about a play that turned out to be about only two words was somehow insufficient. "I was pretty sure I got it. But I was dissatisfied. I thought, 'Dammit, I want a real Godot, a tangible Godot.'"

As it turns out, he found one.

In the early 1990s, in an obscure essay by the Canadian literary critic Hugh Kenner, Paterson learned that Samuel Beckett, asked how he had come up with the name Godot, had once (and apparently only once) mentioned a professional cyclist named Roger Godeau. Beckett, an avid rider, was a big fan of professional bike racing.

So Paterson went in search of Godeau (heh). "He was very hard to find," Paterson said over the telephone. By now we'd been speaking for almost an hour. The connection was surprisingly clear. "I was under the impression that he was a cyclist in the Tour de France. And he wasn't."

Inquiring among elderly Parisian cycling cognoscenti, Paterson discovered that Roger Godot/Godeau was not a Tour rider, but a mid-20th-century indoor track cyclist, a velodrome racer. He had a reputation as a stayer, renowned for his endurance and his ability to come from behind. No one seemed to know much about his postcycling existence, but there were rumours he still worked as a taxi driver in Paris.

The longer it took to find Roger Godeau, the more daunting the prospect of actually meeting him became. "Actually, I became terrified of finding him," Paterson said over the telephone.

"Why?" I asked.

"Because, how stupid, to be doing this."

Stupid or not, Paterson kept asking around. Then, one morning in 1994, his phone rings. "It's Godeau," the voice on the other end of the line says. Yes! Hilarious and true! "Someone told me that you are looking for me."

Godeau agrees to meet Paterson the following Saturday, a serendipitous choice that astounds Paterson, because, well, Samedi = Sam me dit = Sam tells me = samadhi, a Sanskrit word for both a state of intense concentration achieved through meditation, as well as a funerary monument. Except that this time it's not Beckett who is making the joke.

The moment Paterson climbs out of his car a week later in front of Roger Godeau's house, he notices a patch of grass on a little parkette across the street. Next to the patch of grass are a tree and a stone. Weird: just like the set of the play. But there is no record that Beckett ever met Godeau.

Roger Godeau answers the door, a stout, bald, friendly man. "Why have you been looking for me?" he wants to know. This is all true, by the way, even though Paterson refers to his book as "a semi-fiction." Paterson can't bring himself to say – his quest now seems even more ridiculous – so he mumbles something inane about being interested in the name Godeau.

"He looks at me and smiles," Paterson writes in Searching for Godot, "but it is a strange sort of smile, a smile that seems to know something. Does he guess the real reason? Have there been others before me with the same idea?" Whereupon Roger Godeau walks over to a bookshelf and pulls out an album of clippings. "I was born on September 21, 1920, in a small town called Veneux," he tells Paterson. "The towns of Samoreau and Samois are just up the river." Of course they are. More puns.

Paterson eventually has to ask. "What does the name Godeau mean?"

"It means Godeau, my name, me," Godeau replies, as if this were the most obvious fact in the world. Midway through his cycling career he had suffered a crisis of faith, and then managed a comeback. After retirement, he drove a taxi, and honked every time he passed the spot where the Vélodrome d'Hiver, the famous racing arena, once stood. (Hemingway was an habitué, and so was Beckett.) Godeau won the famous Six Day Race at the Vél d'Hiv in 1956. "There were moments of great joy and happiness for me in those days," he tells Paterson.

Paterson asks if he has ever heard of a play called En Attendant Godot. Yes, Godeau has heard of it, but has never seen it.

"Do you think you might be Godot?" Paterson asks.

"But I am Godeau!" Godeau says, and laughs. It could be a line from the play.

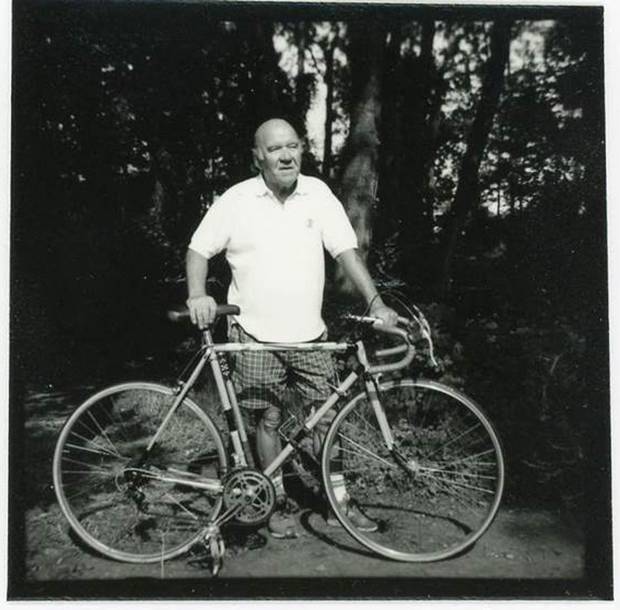

A week later, he takes Paterson for a bike ride. Paterson, more than 30 years his junior, finds it hard to keep up. "Let me know when you're tired!" Godeau sings back to Paterson, ringing his bell. Later, he lets Paterson take a rare photograph of him.

Reading his book, I couldn't believe Paterson had actually found the physical man who may have been the original inspiration for one of the ongoing metaphorical mysteries of 20th-century literature. I now said as much on the phone. "Godeau the cyclist is not 'the' Godot," Paterson quickly replied. "There were many. There are moments when Godot could be Beckett or could be Joyce. But this Godeau is a real Godot." He is, Paterson claimed, "my Godot!"

Roger Godeau. Taken on July 29, 1994.

© IAN PATERSON

By the time I hung up a few minutes later, I had been on the phone to Paris for well over an hour. I thought about my conversation with Paterson for days, buoyed through the tornado of mistruths and distractions that issued from the White House in the meantime. (This was after the court rejected Trump's first Muslim ban, and before Trump accused Barack Obama of tapping his Trump Tower phone.)

I'm not suggesting that thinking about Waiting for Godot – a play about the futility of an uncommitted existence, and possibly of a committed one as well – is a replacement for standing up to a volatile autocrat who could, through carelessness or ignorance or narcissistic need, bring about the nuclear end of the world. (In which case, waiting for Godot and waiting for Trump will have their similarities.) But the more we let Trump and his team of media manipulators set the agenda of what we think about and therefore feel, the more we let them control how we live. Orwell flagged precisely that danger in 1984. "With the development of television, and the technical advance which made it possible to receive and transmit simultaneously on the same instrument, private life came to an end … The possibility of enforcing not only complete obedience to the will of the State, but complete uniformity of opinion on all subjects, now existed for the first time."

This is why Paterson feels important. His example, of someone dedicated to an entirely personal, private and individual quest, helps you remember, in the discouraging mayhem of a relentless and apparently unstoppable bare-knuckle political fight, what you might be fighting for in the first place: the freedom to be obsessed not with what the government wants you to think about, but with everything else.

Roger Godeau, the most likely namesake of Samuel Beckett's Godot, died in 2000. He was riding his bicycle when it happened. His beloved cocker spaniel died a few months later. The dog's name, of course, was Sam.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE'S IAN BROWN