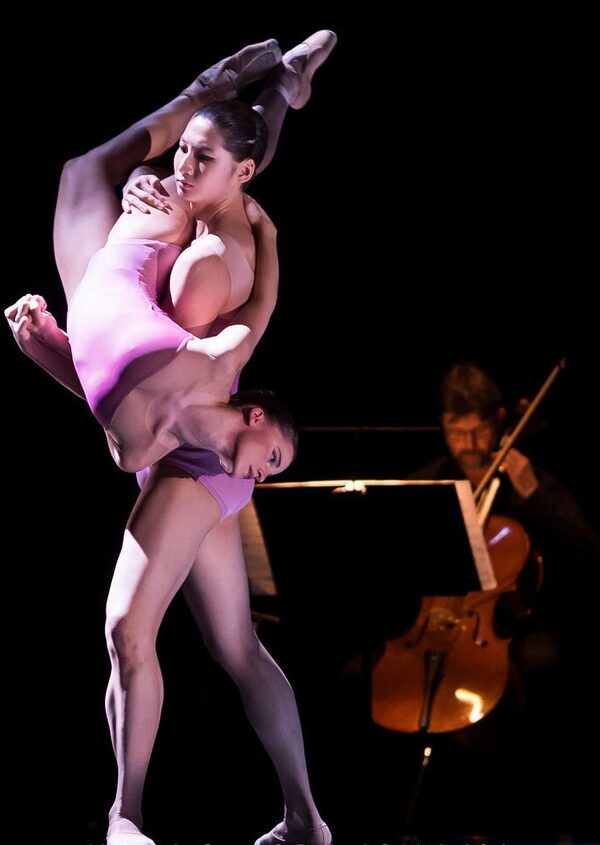

Dancers from the Dutch National Ballet perform Tu me manques, a new work by Canadian choreographer Kirsten Wicklund.Supplied

When former Ballet BC artistic director Emily Molnar was asked to consider leading the Netherlands’ top modern dance company, the first thing she did is call a fellow Canadian to talk all things Dutch dance.

Crystal Pite, a Vancouver native regarded as one of the 21st century’s top dancemakers, had been serving as choreographic associate at Nederlands Dans Theater since 2008, and Molnar had a question for her.

“If I do this, would you stay on board?” Molar asked. “Absolutely,” Pite responded.

With that endorsement in hand, Molnar became NDT’s artistic director in 2020. Four pandemic-interrupted years later, she just celebrated the second work by Pite to premiere under her tenure at NDT, and is preparing to lead the company on a North American tour.

Dancers from Nederlands Dans Teater appear in Figures of Extinction, a collaboration between Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite and British theatre director Simon McBurney.Rahi Rezvani/Supplied

Perhaps not coincidently, the recent Pite premiere came less than a week after she and Molnar had toasted a Dutch milestone for a fellow Canadian choreographer: Kirsten Wicklund, a former member of Ballet BC under Molnar, created her first mainstage work for Dutch National Ballet’s junior company. Tu me manques made its debut Feb. 3 to rave reviews in the Dutch press for her “inventive and atmospheric” duet.

On Feb. 29, Ballet Edmonton announced that Wicklund would become artistic director of Alberta’s leading dance modern company in September, replacing Wen Wei Wang, who had previously hired her as a visiting choreographer. Wicklund says she intends to continue guesting in Europe occasionally, and is especially hoping she can continue her relationship with the Dutch National Ballet.

The Netherlands may be a tiny country, but it’s a big deal in the dance world. And NDT, which turns 65 this year, has been a leading force in contemporary choreography for decades. Dutch National Ballet, meanwhile, has also become known for commissioning innovative projects (such as a contemporary film version of Coppélia) and welcoming top dancers as Olga Smirnova, a star Russian ballerina who defected from the Bolshoi Ballet.

Molnar acknowledged that she benefits by moving to a country that subsidizes for the arts at a higher rate than Canada. After the Second World War, the Netherlands prioritized reconstructing its cultural infrastructure. In other European countries, metropolitan areas often have their own state-sponsored performing arts troupes (Such as the “Staatsopers” system in Germany, or 19 national choreographic centres in France.) The Netherlands chose a different model: Situating ballet in Amsterdam, modern dance in The Hague and giving both companies mandates to travel.

Figures of Extinction premiered Feb. 8, the middle section of a triptych commissioned by NDT artistic director Emily Molnar.Rahi Rezvani/Supplied

“Every time we do something, we do a Dutch tour,” Molnar said. Dancers rehearse in The Hague, get on a bus, perform and come home, usually all in one day. “And then there is the international touring.”

NDT’s coming North American tour begins with Montreal’s Danse Danse series at Places des Arts from March 20-23, and continues at National Arts Centre in Ottawa March 27-28. Pite’s latest work, created in collaboration with English theatre director Simon McBurney, is not on the Canadian programs, sadly. (What NDT debuted in The Hague earlier this month is Part II of what Pite and McBurney envision as a triptych, scheduled to be completed next year.)

Instead, Montreal and Ottawa audiences will see a piece by the Dutch siblings Imre and Marne van Opstal, a new work by Israeli choreographers Sharon Eyal and Gai Behar and a classic by William Forsythe.

It’s Forsthye, the American choreographer who lead Ballet Frankfurt from 1984 through 2004, who binds Molnar and Pite together. Both joined Ballet Frankfurt in 1990s, lured by Forsythe’s angular movement set to unconventional music.

On Feb. 29, Ballet Edmonton announced that Wicklund would become artistic director of Alberta’s leading dance modern company in September, replacing Wen Wei Wang.Michel Schnater/Supplied

Now 50, Molnar was 10 when she left Regina to study at Canada’s National Ballet School in Toronto, eventually joining the company before moving to Germany. Pite transitioned from professional dancer to choreographer, creating new work mostly in Europe and for her own Vancouver-based company, Kidd Pivot.

Molnar, however, returned to Canada to dance with Ballet BC, became artistic director in 2009 and turned a company on the brink of bankruptcy into the country’s leading nurturer of choreographers and exporters of new work.

“I feel like we really accomplished something,” Molnar said. “I was just trying to take the company to that next step.”

The Globe and Mail put it a little more boldly: “Emily Molnar, the triple threat Canadian ballet desperately needs,” was the headline when the paper profiled her in 2016, referring to her abilities as a choreographer, administrator and artistic planner.

Wicklund, meanwhile, was raised in the Vancouver suburbs, trained at Goh Ballet Academy and had long dreamed of dancing professionally. Then she spent the 2008-2009 season with the Washington Ballet’s studio company, filling out roles in The Nutcracker and other large-cast ballets. She briefly danced with Complexions Contemporary Ballet in New York, became a certified yoga teacher and bounced back to Vancouver in 2014, just in time for Molnar’s Ballet BC heyday.

“Those years really formed me as an artist,” Wicklund said of her seven years in the diva-free company focused on new work. “Emily was creating a culture that was very special.”

Molnar’s 2020 departure from Ballet BC proved to be a “heartbreaking” creative catalyst for Wicklund. Without the leader she admired so much, she opted to move on as well: “I needed to go elsewhere and step into a new community and new environment, and ask myself to be uncomfortable again.”

Even though she was seriously dating a Ballet BC colleague, Wicklund moved to Europe in 2021, with the goal of not only dancing, but making connections that would boost her choreographic career. At Belgium’s Opera Ballet Vlaanderen, she danced works by Eyal, Pite, Forsthye and a host of others.

Choreographic opportunities came quickly, too. Last summer, she was selected to participate in the New York Choreographic Institute, a prestigious workshop affiliated with New York City Ballet. (Canadians Alysa Pires and Ethan Colangelo were chosen in 2021 and 2022, respectively.)

With premieres scheduled at both Dutch National Ballet and Ballet Edmonton for the 2023-2024 season, Wicklund realized that dancing full-time in Antwerp was going to be difficult. Yet the roster included more choreographers she wanted to collaborate with, and another opportunity to perform on pointe. (“I wanted one more stab at that,” Wicklund said. “Ballet is my first true love.”)

That’s how her final bows with Opera Ballet Vlaanderen ended up being Feb. 4, one day her after her premiere in Amsterdam, and five days before one of her pieces was onstage in Edmonton. Thankfully, all her trains and flights were on schedule, and Wicklund even had time to (unsuccessfully) attempt to renew her driver’s licence.

Tu me manques made its debut Feb. 3 to rave reviews in the Dutch press.Nina Tonoli/Supplied

She and her husband, videographer and dance artist, Peter Smida, will move from Vancouver to Edmonton before the start of the 2024-2025 season, although they are guaranteed to spend some time on planes: Opera Ballet Vlaanderen has invited her back to a create a new work for her old company in December.

“I’ll continue my relationship with them,” she said. “This is the exact perfect outcome.”

Both Pite and Molnar plan to follow her career closely. Unfortunately, they were unable to attend Wicklund’s Dutch National Ballet premiere while they were prepping for NDTs winter show in The Hague. But they’ll have plenty of chances: both new works are now touring Holland with their respective companies.

Molnar looks forward to seeing Wicklund’s duet, which features one female dancer on pointe and another in slippers, and says she’ll continue to support her former dancer’s career in company leadership and choreography. Wicklund’s work is essential, Molnar said, because she’s a female choreographer committed to bridging ballet and contemporary dance.

“She has a real joy to work on pointe,” Molnar said of her protégé. And more importantly, “she’s a very special person and artist.”

Keep up to date with the weekly Nestruck on Theatre newsletter. Sign up today.