Hanging around with Dashiell, recently 4, is like hanging around with a gravity-free volume of talking liquid mercury: he expands and contracts and stops and flows, conforming to the shape of whatever surface he finds himself on: rug, chair, corner, Mummy.

But talking to Dashiell while he watches Paw Patrol, the Canadian-made preschool animated TV show and toy phenomenon, is to converse with someone in a hypnotic trance.

If you ask Dash which characters are which, three times, you will get no answer. Dash knows you're there, but he doesn't care. He has seen this episode, Pups make a Splash, on Netflix–well, okay, how many times have you seen it, Dash? Dash? Dash! Maybe you decide to nudge him.

"Hmm?" Still looking at the screen.

"How many time have you see this one?"

"Sixty." Small smile.

"Come on, no way."

"Thirty." He lets the word fall out of his mouth sideways, his eyes never straying from the screen in front of him. He's like a Straussian classicist who knows the plot of the Odyssey by heart but loves rereading the same scenes over and over again, sucking new meaning from each take.

But what meaning? It's impossible to tell. When a pup shouts its possibly cringe-making catch phrase – "No job is too big, no pup is too small!" – Dash croons it too. When the pups roll around with their master Ryder at the end of every adventure, Dash slides to ground and rolls around himself.

Sign up for our weekly Parenting & Relationships newsletter for more columns and advice

Such devotion mystifies any number of parents, whether they’re the kind who don’t mind the show, or the kind who resort to blogs and comment threads to accuse it of being simplistic, quasi-fascistic, ultra-materialistic, and repetitive. When Dash was younger, he insisted his mother, Cassandra Drudi, sing the Paw Patrol theme song as a bedtime lullaby, which drove her crazy. If you ask Cassandra if she likes Paw Patrol, she says “Do I like it?,” and then she pauses. “Well, I don’t dislike it.” It’s a common reply. “There’s something completely unobjectionable about Paw Patrol,” another parent admits. “Which doesn’t mean to say you love it. At least it’s not violent.”

In the gentle world of preschool television, whose hallmark has always been a placid, almost interstellar calm (Mister Rogers' Neighbourhood, Teletubbies, Peppa Pig), Paw Patrol has created a new genre: action-adventure, with puppies.

The show is a global phenomenon: the top U.S. TV preschool show with two-to-five-year-olds for two years running, and watched in 160 countries; a commercial and holiday juggernaut responsible for $300-million a year in toy sales, and named by no less than Amazon as one of the top 10 Christmas toys for 2017; and a secret parental godsend that becalms hypermobile preschoolers for 22 minutes at a time, albeit possibly by turning them into drone-yielding materialists.

Meanwhile the Paw Patrol Lifesize Lookout Tower, a 60-centimetre-tall replica of the cartoon lookout from which every episode of Paw Patrol begins, is still in stock for the holiday season, and sells for $130. Ow.

A Paw Patrol who's who

Slide to view

The plot structure of Paw Patrol is almost an algorithm, stamped from a mould. The sameness reassures preschool kids, who are nervously individuating from their parents; the adventure of a specific plot emboldens them and urges them on.

The program, obviously, is an extended ad for the toys. But formal advertising isn't permitted on preschool television, which is why the often-repeated opening sequence, with its upbeat theme song, is an especially brazen Spin Master Corp. product placement, fulsomely displaying the puppy kennels that turn into vehicles that children then want.

Each episode begins when someone, usually a hapless adult from an inclusive range of colours and races, runs into mild trouble (real menace is still a no-go in preschool TV) in Adventure Bay where the pups live communally with their 10-year-old tech-wizard master, Ryder. To a three-year-old, a 10-year-old is a god. The panicky adult calls Ryder on his ever-present cellphonic device, and Ryder selects the pups he'll use for the rescue, based on the working skills of their breeds.

Chase, the gruff but golden-hearted police dog who is allergic to cats, is a German shepherd who wears blue and drives a police SUV. Marshall, the klutzy but well-meaning Dalmatian, drives a red fire engine. Rubble, a bulldog, is in construction, and has a yellow hard hat and a convertible dump truck/crane/bulldozer. Rocky's a mutt, so he's scrappy and resourceful and wears green (and is afraid of water): his kennel converts into a recycling truck. Are you beginning to get the picture? Zuma is a chocolate lab who wears orange and commands a hovercraft, because he's a waterdog. (Some adult viewers aren't sure of his gender, but female pups on the show always have eyelashes, and Zuma doesn't.) Skye, the only female in the main crew, is a perky cockapoo, and a pilot. Her plane, of course, is pink. Preschoolers like the prescribed. (Everest, a female husky who lives in the mountains with a ski patrol dude, shows up in later episodes.)

In their colour-coded hats and costumes, the pups bear a resemblance to the Village People. This may be intentional.

By the four-minute mark in a standard 11-minute episode, Ryder has devised a plan by which the pups save the victims with the help of snappy technology in their transforming vehicles and backpacks. Preschool is when kids begin to think logically for the first time, and when they first long to be more capable than they are. Technology, meanwhile, is the unspoken star of Paw Patrol. The pups become more sophisticated with each season, starring in visual tropes stolen directly from the Indiana Jones and Bond movie franchises. As season 5 starts, the pups occupy a kind of military-animational complex, and command a stealth-enabled Air Patroller plane, a Sea Patroller ship, flight-enabling backpacks, scuba outfits, night-vision goggles and even surveillance drones. (One of Skye's vehicles is a copy of a camera-equipped drone Spin Master markets to older children. Brand loyalty is best bred early.) Once the rescue is enacted, everyone gets a dog biscuit and falls into a pile of giggling happiness.

Ronnen Harary co-founded Spin Master Corp. with Anton Rabie and Ben Varadi, who are now reportedly worth $1.4-billion each.

MARK BLINCH/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

This is a scoop: the look of Ryder, the master of the pups, is obviously based on Ronnen Harary, co-founder (with Anton Rabie and Ben Varadi) of Spin Master Corp., the Toronto-based toy-making behemoth that created Paw Patrol. Harary is at this moment sitting in the lounge half of his book- and toy-lined 16th-floor office at Spin Master’s headquarters in downtown Toronto. He is the picture of unflappable, friendly, Ryder-like alertness: navy sweater, jeans, boots, a bottle of some kind of expensive green juice. And, of course, there is the giveaway, the meticulously back-swept, up-combed hair, much the way Ryder wears his. The difference is that Harary, 46, has a beard.

The co-founders were undergraduates at the University of Western Ontario in 1994 when they bought the license to an Israeli toy, the Earth Buddy – a face drawn on a nylon stocking filled with grass seed that grew green hair as you watered it – and sold half a million of the trolls to K-Mart. Twenty-three years later, a string of hits such as Air Hogs, Devil Sticks, Bakugan, Hatchimals and now Paw Patrol have transformed Spin Master into the world's fourth-largest toy maker, with 2016 revenue of $1.3-billion (U.S.), up more than 30 per cent from the year earlier. Worth a reported $1.64-billion, Harary is the 70th richest person in the country.

The trio were especially good at making the creation of successful toys look like a barrel of instinctual fun, when in fact it's a deeply premeditated, intensely secretive process, underpinned by child psychology and – since at least the 1970s, when Star Wars happened – the use of television as a multiplatform marketing tool.

Bakugan was an especially important toy that way for both Spin Master and Paw Patrol. A set of collectable plastic magnetic marbles, each of which transforms into a different creature, Bakugan was licensed in 2005 off nothing more than a sketch by a 23-year-old Japanese inventor. Harary and Japan's Sega Toys then created the toy and a TV show worth (Harary's estimate) $1-billion.

"That was the moment I realized what entertainment can do for toys," Harary says, sipping his green goop. "Twenty-five per cent of toys sold in the marketplace come from TV or movie-based characters."

He created a division, Spin Master Entertainment, which, by his own admission, was having only moderate success by 2010 when he had another brainwave: a transformational toy – a toy that is one thing that becomes another thing, and thus two things in one – for preschoolers between the ages of 2 and 5.

There were only three problems with the idea. Spin Master was considered an older boy's toy company at the time; it had no experience in the tricky preschool category; and preschoolers lack the digital dexterity required to operate a transforming toy.

"The idea of transformation had been around for a long time," Jennifer Dodge remembers, "but it was typically for an older audience of 6- to 11-year-old boys." Dodge, a Memorial University graduate who spent a decade thinking up preschool shows for Halifax's DHX Media Ltd., was hired by Harary to transform his obsession with transformation into a new show (and, therefore, a new toy).

Catherine Demas, Dodge's alter-ego on the toy-design side of the company, shared her concerns. "The preschooler is very different from the 8-year-old," Demas told me recently in Spin Master's toy design lab near Culver City, in Los Angeles. "The world is very small when you're that age. Making something relatable is so important. It has to be aspirational, but it has to be within their grasp."

Three- to five-year-olds live in the continuous present, in the concrete here and now of touch and see and hear. They don't understand outer space, which is too abstract for kids still trying to figure out how to use a sippy-cup. On the other hand, My Little Pony works, because hair-play is a long-recognized preschool "play pattern." Preschoolers grok babies and motherhood and vehicles and uniforms and dogs and cats because they see them everywhere. But transformation, for preschoolers? No one had ever tried it before.

Dodge nevertheless put out a call for proposals to half a dozen trusted toy and story creators around the world. (Yes, there is a list.) The returned proposals featured dinosaurs, outer space (!), robotic bugs, and a fourth from an Englishman named Keith Chapman.

Chapman was famous. He invented Bob the Builder, the iconic 1990s British stop-action (or Claymation) television character who made a virtue of quotidian plodding while he developed into a $5-billion franchise and joined the ranks of Thomas the Tank Engine and Dora the Explorer in the preschool TV hall of fame. Bob was a dork, but he was a calm, reliable, clay dork, the kind preschoolers love – plus he had vehicles. "It was a pretty loose brief," Chapman recalls of Dodge's transformation proposal. "The key element was that it involved emergency vehicles. It was a little bit like an advertising brief."

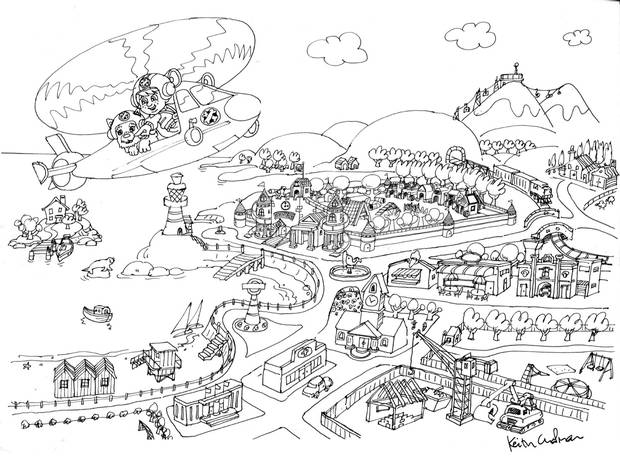

Chapman's brainwave? Rescue dogs that rescued people. "That was a very simple core idea," he recalls. His first 2010 sketches of "Raffi & the Rescue Dogs" were nothing like the shiny, computer-animated Paw Patrol pups of today; they looked more like Oxford dons

Keith Chapman’s illustrations show the early beginnings of the Paw Patrol concept.

COURTESY OF SPIN MASTER

But Chapman and Dodge thought the idea had depth. Ninety per cent of the audience for Bob the Builder had been boys, but puppies in rescue vehicles had a chance of crossing the gender line. "And," Chapman recalls, "it was a strong enough idea that you could have a movie too."

Chapman is listed as Paw Patrol's creator to this day, and the series' best year has already surpassed Bob the Builder's. "We're talking in the millions [of pounds sterling] a year," he told me in a recent conversation. He's making so much money off Paw Patrol, he recently moved to Monaco for tax purposes.

Jaxon Mercey holds his forearms at shoulder level when he's recording a double episode of Paw Patrol in the sound booth at Spence-Thomas Productions in Toronto. Jaxon is the voice of Ryder. He's Paw Patrol's third Ryder so far–at least, if you don't count the very first one, whose voice cracked three episodes in and had to be rerecorded.

Jaxon's 12, in Grade 7: medium height, stylishly top-massed curly blond hair, T shirt, jeans. He wants to be an actor or a goalie in the NHL. He looks slightly older than he sounds. Paw Patrol demands three hours of Jaxon's time every fortnight, for which he makes at least (my estimation) $35,000 a year. He's recording a show from season 5 today, one that won't be seen until next spring, and has been Ryder since late in Season 4.

"I certainly notice the difference," his father and manager, Derek Mercey, says of Jaxon's Ryder compared with his predecessor's, "but I'm not sure children four years old notice the difference."

Breaking voices are the occupational hazard of children's animation. Jaxon knows it will happen to him one day as well: no one can be Ryder forever. When the actor who plays Chase was replaced last spring – you'll hear the new voice early next year – 75 kids auditioned.

Preschool may be TV's simplest genre, but it requires a crew of more than 218 to make Paw Patrol. Each 11 minute episode takes 50 weeks to deliver: eight weeks alone for concepts and scripts, and many more for recording, animation, the painstaking building of 3-D "assets" (new backgrounds, such as the interior of the Air Patroller or the exterior of the Temple of the Monkey Queen), visual effects (clouds, dust trails, odours) and all that follows to post-production. At Guru Studio in Toronto, where 136 people work on Paw Patrol full-time, a computer animator aims to create a quota of 35 seconds of action a week, or about seven seconds a day.

"It's pretty straightforward on this one," a producer in the control booth says over the mike to Jaxon. "Nice and sweet."

"Aw, you pups!" Jaxon rehearses. Ryder is expressing his affection for his pups. He does this a lot.

"Lots of energy."

Jaxon repeats "Aw, you pups!" three times in a row. He has his arms up, as always, punching both hands into the air when he wants to convey enthusiasm. It's a challenge to make Paw's innocuous, non-threatening dialogue – "Okay, Rocky, back up!" – compelling.

"Do you ever want to shoot heroin at the end of the day?" someone says, after a particularly long set of takes oozing the treacly goo of Ryder's endlessly upbeat enthusiasm. "Yes," comes the answer. "Except that people in kids' television can't afford heroin."

Despite the toys it sells for Spin Master, Paw Patrol itself is not "acutely profitable," according to Ronnen Harary. Ironically, for all the attention to story-telling Dodge and her team put into making a show that four-year-olds will remember for the rest of their lives – and that is her stated aim – children's television is often seen as a means to an end, and so ranks low on the entertainment pay-and-status ladder. "HBO, FX, Showtime, broadcasters, sports, then kids," a long-time Hollywood agent explained recently, ranking the steps from top to bottom. He thought for a moment. "Then porn, I guess."

Jennifer Dodge and Jamie Whitney looks over storyboards for their show Abby Hatcher at the Spin Master office in Toronto. In 2011, Ms. Dodge’s team convinced Nickleodeon to partner with them on producing Paw Patrol, and Mr. Whitney was its first director.

MARK BLINCH/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

By January, 2012, Jenn Dodge and her team had refined the concept of Paw Patrol enough to persuade Nickleodeon, the children’s animation arm of Viacom, to be Spin Master’s partner. (They split the cost of production. Spin Master retains Canadian TV rights, and worldwide toy rights; Nickleodeon gets worldwide TV rights and non-toy merchandising – sheets, pyjamas, backpacks. Both get a share of the other’s take.)

But the pups looked nothing like the iconic Paw Patrollers they have become. Visually, they were still rescued dogs, as Keith Chapman originally conceived of them.

Earlier models of the Paw Patrol characters, led by “Robbie” (later Ryder).

COURTESY OF SPIN MASTER

Scott Kraft, the show's first writer, and Jamie Whitney, it's first director, quickly ditched the rescued dog theme – it was too much backstory to convey in an 11 minute episode. They concentrated instead on the "pro-social" idea of pups rescuing others. (Preschool shows have to be pro-social under Canadian broadcasting guidelines: there is no equivalent of South Park for three-year-olds.) Kraft and Whitney introduced the show's famous catch phrases – "This pup's gotta fly!", "Chase is on the case!" – because being able to recite them makes small kids feel smart. They added slapstick and puns and endless alliteration because there is evidence humour makes young children more resilient. Spin Master claims Paw Patrol's audience is 48 per cent female and 52 per cent male, a rare blend in the toy business.

"The way I always looked at the pups was as siblings," Kraft says. "Paw Patrol is a bunch of little kids who do aspirational things."

The Paw Patrol's 10-year-old leader, whom Chapman had named Raffi and then Roddy (too British), became Robbie (too mundane) and then Ryder. Everything pup-related was debated endlessly: names, sizes, ages, breeds. The original transforming backpacks, so big the pups became beasts of burden, were shrunk and redesigned so a preschooler could open and close one on his or her own. "Whatever we begin to do on TV," Dodge says, "we really want our toy designers to replicate it. So that when the kid goes to buy the toy, it looks like it is exactly the same."

In early sketches, the pups' hind legs are hinged, as real dogs' are. In the final product, they're straight. "It makes them more puppy-like," Dodge says (not to mention more toddler-like), "but it also makes them capable of standing up as toys." The vehicles became less puffy and more aggressive; the pups' eyes and ears grew huge. The characters in the show, in other words, began to look more and more like toys.

The show debuted on Nickleodeon in the United States on Aug. 12, 2013, six months before a single Paw Patrol toy appeared. (They're engineered in L.A., but manufactured in China.) There's a live Paw Patrol stage show (tickets can run to $150 a seat) and a road show. You can be a Paw Parent. A feature film is in the works. And of course there are hundreds of Paw Patrol products: pups and their pals in plastic and plush, vehicles and video games, game books and playbooks and sound books and badges, an upholstered chair and a toddler bed, bath sets and placemats, a three-in-one Paw Patrol Potty (no job is to big, no poop is too small!), mini-pups and plastic playsets at pinpointed multiple price points. There is even a Paw Patrol Advent Calendar, with a plastic Paw Patrol figurine behind every door. Think about the birth of Jesus, then behold the puppy saviours! Last month – in return for the usual fee – Chase was a balloon in Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City. There were people on the Paw Patrol team who cried when they heard the news.

The #MacysThanksgivingDayParade is only one week away!! Chase is getting ready to take the NYC sky! Where will you be watching the parade from?! 🐶❤️ pic.twitter.com/YtDTp8GYNZ

— Spin Master (@SpinMaster) November 17, 2017

The serious question is: Is the show good for children? Are they really learning "pro-social" behaviour, such as good citizenship and team work from Paw Patrol's tame but antic technology-obsessed dramas? Or is Paw Patrol the toyetic gateway drug to a lifetime addiction to television and capitalism and more and more stuff, and the stasis that entrapment implies?

Here is the unfathomable answer: It is both. The toy business is a business, and a capitalistic democracy does not come without the acquisitive attachment, at least in currently available models. Paw Patrol is a television show about young dogs who are never cynical, that is nevertheless devoted to transforming – there's that word again – your child into a consumer before he or she can read.

Harary, a sincere billionaire who lives in Toronto's Little Italy, will tell you: "I don't think you can mastermind something like Paw Patrol cynically." And he's right. He cites the example of Chickaletta, the hen that Paw Patrol's Mayor Goodway carries in her purse for no apparent reason. "You'd never put a character like Chickaletta in if you were simply trying to sell," Harary says. It is still possible, however, to buy a 10-inch-high Plush Pup Toy Chickaletta, made from about 50 cents' worth of premium Velboa plush fabric, for $14.99 on the Paw Patrol website. In the toy business, idealists and opportunists play together all the time.

But I'll leave you this to think about, by way of wondering what children who love Paw Patrol are trying to tell their parents. A few weeks ago, I watched the program with two young acquaintances of mine, Cy and Jane. Jane is 3, prime Paw Patrol age: she loves Marshall's slapstick pileups. Her favourite pup is Skye, "because she flies." But she gets to watch Paw Patrol less often now that her six-year-old brother Cy has moved beyond Adventure Bay and started watching New Looney Tunes, which is what Bugs Bunny is called now. Cy was headlong obsessed with Paw Patrol for two years. He now prefers the more raucously hilarious and ethically complex violence of Bugs pulverizing Yosemite Sam again and again, stories in which events are not so crisply good and bad, in which the good guy is the tricky guy who does bad things to the worse guy. Morally, next to Paw Patrol, Bugs Bunny is like Heidegger.

Cy seems more interested these days in what is real and what is not: he's growing up. "Yosemite Sam gets blown up into a pile of ash," Cy says, but then Sam is whole again in the next scene. "How can that happen?" He has an even harder time believing Paw Patrol's smooth reality. "They make it seem for sure, but I don't think it's real. The pups, they never go on leashes. And pups can't drive cars." These discrepancies don't matter to a preschooler, of course, because in the preschool lane you take the world as it comes at you. Then you get older, and start asking questions. Recent evidence suggests that 7 is the age children develop the capacity to ask "what if" questions – the age they begin to understand regret.

It moved me to be with Jane and Cy on either side of that grave and delicate divide. Cy got bored by the second episode and asked Jane for a hug, as if he sensed he was moving into a more complicated place, and she blithely turned him down, certain he would always be there to ask. All this, while the Paw Patrol pups saved Cap'n Turbot's blimp with their transforming backpack accessories.

Then Jane laughed at Marshall again, and said, “I like Chickaletta. I like Chickaletta.” In benign and balmy Adventure Bay, with the pups, what you see and like is what is good. Why not stay there as long as you possibly can, sweet child? Because once you leave those sunny climes, you’ve left forever. The pups in Paw Patrol mark the spot where that happens.

Parenting & Relationships newsletter

Sign up for more advice, news and opinion pieces in your inbox to help you navigate modern life.