Rosalie Trombley at Windsor's AM800 CKLW as music director.Jackson/Handout

On Nov. 14, 1974, an AM radio station in Southwestern Ontario welcomed an unlikely guest disc jockey: Elton John.

Billed as “EJ the DJ,” the British pop star sat in on Windsor’s AM800 CKLW (a.k.a. “the Big 8”) for an afternoon slot, throwing to records by Cher and Chicago funk band Rufus. Although John’s short-lived stint as a local drive-time disc jockey is absent from the new Elton John musical biopic Rocketman, it remains, for those living in Windsor/Essex County, and the neighbouring Metro Detroit area, a memorable piece of local minutiae.

Before signing off, John dropped the needle on his chart-topping 1974 single Bennie and the Jets, dedicating the song to CKLW listeners in Motor City. “This record is a Deeeeeee-troit record!” John exclaimed, in full, hammy seventies radio-pitchman mode. “You made it! Thank you!”

Certainly, the Windsor-Detroit area played an important part in pushing Bennie and the Jets – which marked John’s first serious crossover hit among black American audiences – to various No. 1 spots. But there was one person more directly responsible for the single’s success, and – in turn – Elton John’s stateside, mid-seventies breakout: Big 8 music director Rosalie Trombley.

Elton John at Noel Edmonds record shop in the King's Road, Chelsea signing copies of his album, Don't Shoot Me I'm Only the Piano Player.Michael Webb/Getty Images

They called her the girl with the golden ears.

Born in 1938 in Leamington, Ont., a small town on Lake Erie’s northern shore hailed as the “Tomato Capital of Canada,” Rosalie Trombley came of age with rock ’n’ roll. As Ron Base wrote in a 1973 Globe and Mail profile, Trombley was the kind of woman whom one easily imagined “back there in the fifties jitterbugging to Frankie Lymon or Bo Diddley records at some Friday-night sock hop.”

She grew up listening to CKLW. Bud Davies, a DJ who played to the emerging teenage market with his radio show and local TV program, Top Ten Dance Party, was a particular favourite. In 1963, Trombley was hired as a part-time switchboard operator at CKLW. From that post, she observed the station’s inner workings, and learned to handle the personalities of record pushers hoping to get their product played on air. After exhibiting what CKLW vice-president Alden Diehl called “a fantastic feel for what’s right for the station,” she was promoted.

By the fall of 1968, as a single mother of three, she was working as the station’s music director, programming a rangy mix of rock, soul and funk that, boosted by the Big 8’s 50,000 mighty watts and its adjacency to the thriving Motown market, was heard by millions of listeners across 27 U.S. states and four Canadian provinces. (When the meteorological conditions were just so, there were even reports of the station being heard in faraway Scandinavia.)

As CKLW’s music director, Trombley earned the status of, in the words of The Globe’s Base, “probably the most powerful woman in the music business.” She helped break the careers of artists from both sides of the border: Alice Cooper; Ted Nugent; the Guess Who; Earth, Wind & Fire; and Motor City heartland rocker Bob Seger. Indeed, Seger’s 1973 song Rosalie (later, and perhaps more memorably, covered by Irish rockers Thin Lizzy) was named after Trombley, name-checking her as “everybody’s favourite little record girl.”

“Mom was a huge Seger fan,” says Tim Trombley, Rosalie’s son, who now speaks on behalf of his ailing mother. “They were friends, but she didn’t really hear the growth in his music. And I think, somewhat in frustration, he wrote Rosalie; to basically say, ‘I know you know music.'”

Unimpressed by Seger’s fawning (and a little condescending) appeal, Trombley refused to play Rosalie – and threatened to quit CKLW if it ever made the airwaves. Still, that an artist would write a record directly petitioning a music programmer speaks to the outsize influence Trombley exerted.

“If Rosalie said it was a hit, everyone would know it would be huge,” says Maureen Holloway, current co-host (with Darren B. Lamb) of the Darren & Mo morning show on Toronto’s CHFI-FM. (Holloway was the 2018 recipient of the Trombley-inspired Rosalie Award, an annual commendation recognizing “Canadian women who have blazed new trails in radio.”)

That talent for both taste-making and star-making – those “golden ears” that Holloway herself brings up in conversation – tend to dominate discussions of Trombley and her legacy. It’s as if she was preternaturally gifted, able to divine chart-toppers among the many, many records (estimated at 100 to 150 weekly) pushed across her desk by eager promoters. One is reminded of the pithy, Zen-like wisdom of the unscrupulous record exec Hesh Rabkin on The Sopranos: “There’s one constant in the music business: A hit is a hit.”

And Rosalie, the legend goes, had a knack for picking the hits.

Maureen Holloway, seen here at her home in Toronto on May 23, 2019, received the Trombley-inspired Rosalie Award in 2018.Alex Franklin/The Globe and Mail

Such thinking, however, tends to muddy the whole story.

It’s not as if Trombley’s ears were touched by the Top 40 gods, who, in their infinite munificence, floated her 45 minutes up Highway 3 from Leamington to Windsor to grace a border-town radio station, gifting its millions of listeners with her knack for knowing what records people might like.

“She had an exceptional ear,” son Tim says. “But she always had her weekly process.”

That process included weekly calls to dozens of record stores across the Metro Detroit area. Trombley would inquire as to what records people were buying, and what particular songs they were digging. She paid particular attention to CKLW’s call-in lines, tasking staffers with keeping detailed logs of the songs listeners wanted to hear.

In the case of Elton John’s Bennie and the Jets, Trombley’s exhaustive research revealed that John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road LP was selling particularly well in urban, inner-city record shops. As Tim relates it: “Folks were coming in and looking for a single by this guy Elton John called Bennie and the Jets. And of course there wasn’t a single, because it hadn’t been released [as a single].”

Bennie and the Jets was also receiving considerable play on a smaller Detroit-area station, WJLB. (In His Song: The Musical Journey of Elton John, biographer Elizabeth J. Rosenthal credits WJLB late-night DJ Donnie Simpson with breaking the song.) Piqued by the considerable interest in an Elton John album cut among Detroit’s black audiences, Trombley recommended that MCA, John’s label, release Bennie and the Jets as the next stateside single, instead of the torch song Candle in the Wind. In the meantime, CKLW added Bennie to its playlist, and the request lines lit up.

“Later that week,” Tim explains, “Elton John himself called the radio station wanting to speak to my mom.”

She explained that Bennie and the Jets was a chance for John to expand his appeal – not just in the coveted Motor City market, but into the United States’ broader black community, winning him a wider, more racially diverse, audience. Elton John (and MCA) relented. Following CKLW’s lead, other stations across the U.S. and Canada added the song to their playlists, resulting in not only a Billboard No. 1 hit (his second, following 1973’s Crocodile Rock), but John’s first Top 40 hit on Billboard’s Hot Soul Singles.

Elton John and Rosalie Trombley with Windsor’s CKLW AM 800 announcers in 1974.CKLW

Beyond her role in nudging the career trajectories of top-tier global pop stars, Trombley had a deeper influence in the Canadian music industry. When Lana Gay, a broadcaster currently stationed at Toronto’s Indie88, scored her first on-air radio gig, she developed her playlists using what she calls “the Rosalie Method”: pairing intuition with a serious attention to data and audience reception.

“She was a true analyst of culture,” Gay says of Trombley. “She backed up her instincts: not just by doing the boardroom thing, but by keeping in touch with her audience.” Gay sees Trombley as something of an icon – and not just because they’re both Leamington natives. Trombley was a singularly powerful figure in radio at a time when roles for women were seriously limited. “In rock radio, in particular, there weren’t stations that had multiple jobs for women,” Gay explains. “But she had an incredible amount of power, and an incredible amount of influence.”

As CHFI-FM’s Holloway explains, roles for women in radio were historically circumscribed, both on air and off. “You could be a traffic girl – and never a traffic woman – or the giggle girl, there to laugh at the male announcers,” Holloway says. “None of the decision-makers were women. And by none, I mean none.”

Trombley also represents something else, beyond her trailblazing bona fides. She’s an almost romantic figure of another era, when promoters peddled would-be hit records (sometimes accompanied by an envelope full of bills or other stimulating perks) to entice DJs and music directors; when taste was determined from the top down.

“Data drives everything these days,” explains Adam Thompson, program director at Toronto’s KISS 92.5. “That’s the biggest difference between what Rosalie Trombley did in the 1960s and 70s and what we do now. Then, data was literally calling record stores, and seeing what was selling. … Now, we have everything at our fingertips to say, ‘Here’s what songs off a release are driving the most interest.'"

Instantly accessible data – from sales and streaming numbers, to set-list aggregator websites indexing what songs a given artist tends to perform most live – reveal what tunes audiences are responding to, and shape playlists in turn. The era when someone like Rosalie Trombley would listen through scores of records a week to determine the next hit feels, to many in radio, like a bygone age. “It’s a lot easier now,” Thompson says. “It’s not as fun, I’m not gonna lie. You can’t just go, ‘I want this to be a big song!’ Because if you’re not listening to the audience, you’re not doing your job.”

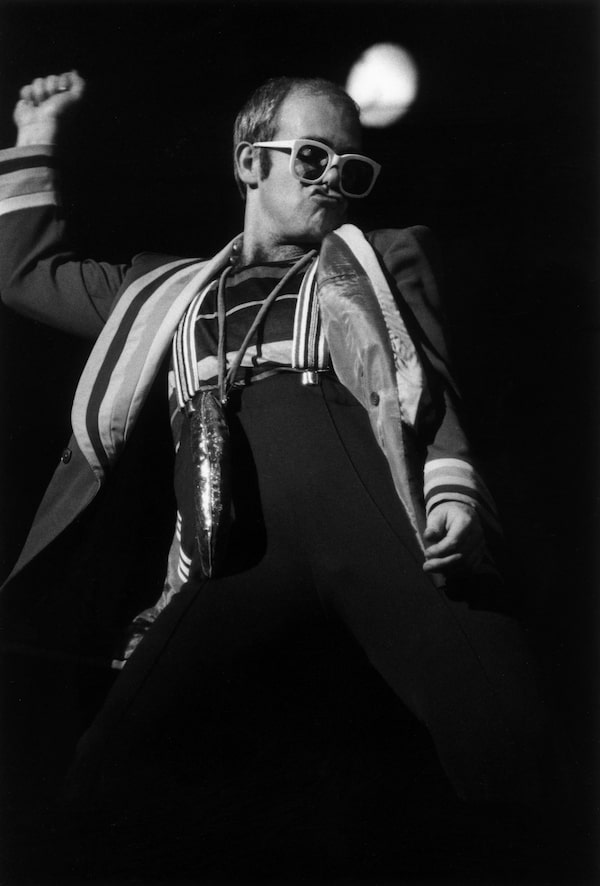

Elton John performs at the Rainbow Theatre, London.Robin Jones/Getty Images

In time, it became harder for Trombley and other decision-makers at the Big 8 to listen to those audiences.

The rise of FM radio stations, coupled with the 1971 implementation of Canadian content mandates, eroded CKLW’s influence. Trombley scrambled to keep pace with shifting market trends and government regulations. But it wasn’t enough. The station transitioned from its eclectic, tastefully curated mix of pop, hard rock and soul into easy listening and, in 1984, was rebranded as a fully automated jazz and big-band station. The remaining stalwarts, including Trombley, were unceremoniously laid off.

Yet, there were some memorable moments along CKLW’s despairing downward slope. The Cancon rules helped break a handful of homegrown artists – April Wine, Gordon Lightfoot, the Five Man Electrical Band – stateside.

And as related in Michael McNamara’s 2004 doc Radio Revolution: The Rise and Fall of the Big 8, George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic even decamped from Detroit to Toronto to record their 1972 double album America Eats Its Young, partly in hopes their Canadian residency, and usage of local studios, would satisfy the requirements of Cancon regulations. Having scored early success in Motown thanks to exposure on CKLW, they knew the clearest path to stardom was bending those golden ears.

John's appearance on Soul Train would have been unthinkable without Trombley’s intervention.Roger Jackson/Getty Images

Still, there was perhaps no greater beneficiary of Trombley’s ears, her hustle, her scrupulous research and her fantastic feel for what’s right than Elton John. A life-long aficionado of soul music, he had dreamed of breaking into America’s black markets. And with Trombley’s encouragement, he accomplished just that. Her dogged support for Bennie and the Jets led, in time, to a memorable appearance on Soul Train, the so-called “black American Bandstand.” It’s a brazen and somewhat bizarre performance, as fantastic as anything conjured in the Rocketman movie (opening May 31), that might have been unthinkable without Trombley’s intervention.

There’s Elton John, whose bedazzled emerald livery and matching bowler make him look like a glam-funk leprechaun, seated over a translucent piano, beating out Bennie, ringed by African-American dancers in Afros and bell-bottoms, shaking loose together. It’s an image of an eccentric English oddball breaking down boundaries, made possible by a hard-nosed single mom from small-town Ontario who broke down plenty of her own.

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.