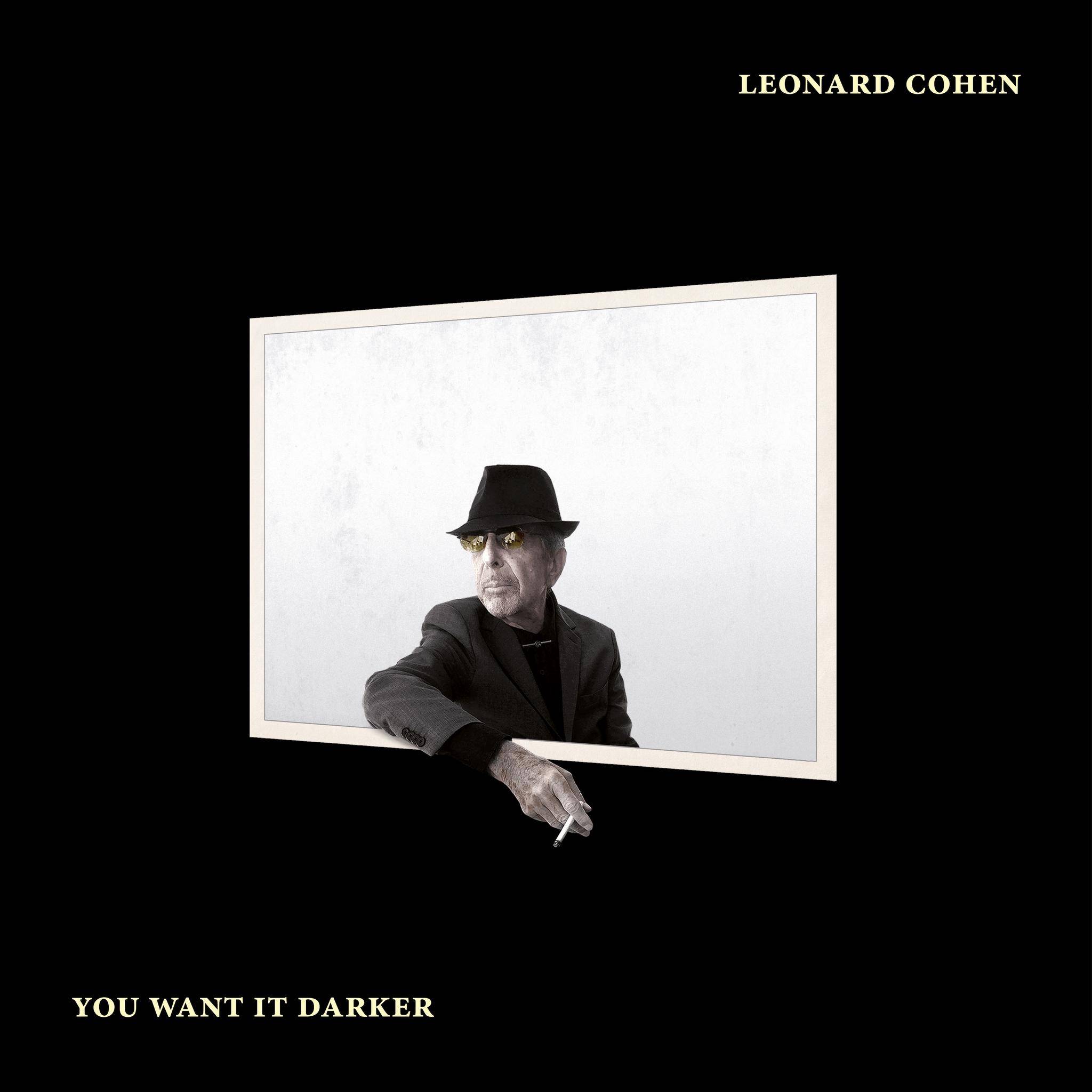

Leonard Cohen is pictured at his home in Montreal, a city that has been both a place to escape and a refuge for the artist.

Charla Jones/The Globe and Mail

Leonard Cohen, age 82, died on Monday, Nov. 7, 2016. Read his obituary here.

The path to holiness starts near a grey stone mansion, and skirts a stone lookout as it winds down the slope many in Westmount still call by its old name, Murray Hill. From the bottom of the park, it's an easy stroll down Côte St. Antoine to Shaar Hashomayim, the synagogue with which the family of Leonard Cohen has been associated for some 150 years.

This is the route that Cohen would have taken from his childhood home on High Holy Days, when he went to the Shaar at age nine to say Kaddish for his father, and when he had his bar mitzvah. He may have traversed the familiar path in imagination much more recently, when he asked the synagogue's cantor and choir to sing on his sombre new album, You Want It Darker.

"He said ‘I’m looking for the sound of the synagogue cantor and choir of my youth,’ " says cantor Gideon Zelermyer, quoting from an e-mail he received from Cohen in November. He could have found singers near his home in Los Angeles to simulate the sound of a Jewish congregational choir, but instead returned to the place where the prayer books of his uncles are still tucked in a drawer in the family’s third-row pew.

Cohen is 82 and fragile, and apparently much absorbed in thoughts of origins and final destinations. Recruiting the choir he heard as a boy is just the latest instance of his deep and complex relationship with Montreal, the city of his birth and the cradle of his longings.

“I have to keep coming back to Montreal to renew my neurotic affiliations,” he wrote on the dust jacket of The Spice-Box of Earth, a collection of poems he published in 1961. More recently, and less playfully, he told an interviewer, “I feel at home when I’m in Montreal, in a way that I don’t feel anywhere else. I just love it. I don’t know what it is, but the feeling gets stronger as I get older.”

Montreal for Cohen has been both a place to escape and a refuge. The family home on Belmont Avenue was certainly a safe haven during his childhood, from the privations of the Depression and from demonstrations by anti-Semites. Home movies from the 1930s and 1940s show Cohen posing with the family's black chauffeur, skiing down the Murray Hill slope and skating on the rink he could see from his bedroom window.

Donald Brittain's 1965 National Film Board of Canada film Ladies and Gentlemen … Mr. Leonard Cohen shows its subject, who had yet to make his first recording, wandering down the Murray Hill path while reading in voice-over from his 1963 novel, The Favourite Game. "The park nourished all the sleepers in the surrounding houses. It gave the children dangerous bushes and heroic landscapes so they could imagine bravery. It gave the muses and maids winding walks so they could imagine beauty. It gave the young merchant princes leaf-hid necking benches, views of factories so they could imagine power."

Cohen discovered the romance of Westmount, and its sadness, too, as his friend Irving Layton pointed out. He mythologized the chic women who "float into dress shops or walk their rich dogs in front of the Ritz." He was of that world; but as a Jew and a poet, was also separate enough to remark that "Westmount is a collection of large stone houses and lush trees arranged on the top of the mountain especially to humiliate the underprivileged."

There are a couple of large churches on the route Cohen would have walked to the Shaar. He went to school with kids from those churches, at Roslyn Elementary and Westmount High, both imposing buildings where anglophone Christians and Jews mingled as they no longer do in the borough's more diversified school structure. Cohen biographer Sylvie Simmons says that between one-quarter and one-third of Westmount High students in Cohen's day were Jewish. He was exposed to Christian pageants at school, and had even gone to church with his Irish Catholic nanny, laying the basis for a lifelong fascination with Christian imagery and rhetoric.

Cohen's spiritual side never completely detached from the carnal, of course – Murray Hill had its "necking benches," where adolescent desire ran up against the stern sexual mores of the 1950s. From his earliest teen years, Cohen's Montreal also included the neon-lit zone of clubs and cabarets that flourished along St. Catherine Street, where he would dream on the sidewalk about the sacred debaucheries going on inside.

Westmount is a collection of large stone houses and lush trees arranged on the top of the mountain especially to humiliate the underprivileged Leonard Cohen

His first public performance with music was in one of those places, in the Birdland jazz club above Dunn's Delicatessen, where in 1958 he read a poem over an improvised piano accompaniment, a form of delivery made fashionable by Beat poets. His Montreal also included McGill University, where he imagined he was participating in a colonial rewrite of Brideshead Revisited, while serving as president of a Jewish fraternity.

He followed a centrifugal path away from the family home on Belmont Avenue, but also threw parties there for his poet friends. He launched The Spice-Box of Earth there in 1961 – after a narrow escape from Cuba during the Bay of Pigs invasion – and posed for Brittain's camera in the panelled front room, while having tea with his mother. When he returned from Greece with his companion Marianne Ihlen, they settled first in the Belmont house, and it was there also that he brought Joni Mitchell when they were intimate in the mid-1960s.

Cohen in those days, with his tendency to mythologize his environment, advanced an unchanging image of Montreal, or at least discounted the notion of real development. "The streets change swiftly, the skyscrapers climb into silhouettes against the Saint Lawrence," he wrote in The Favourite Game, "but it is somehow unreal and nobody believes it, because in Montreal there is no present tense, there is only the past claiming victories." He rented a place on Stanley Street and sometimes lived there, turning it with a friend into an informal art gallery that flourished outside the Montreal gallery scene till it burnt to the ground.

He also loved to affect an outsider's view of the city he knew intimately and well, sometimes holing up at the Hotel de France at St. Catherine Street and St. Laurent, where he could pretend to be "on the lam" and unencumbered. The mentality crystallized in The Stranger Song, a song from his 1967 debut album about an emotional escape artist who always had a highway "curling up like smoke above his shoulder."

Cohen left Montreal, mainly for U.S. cities, once his career took off. But the city is found throughout his music, referenced in songs such as Suzanne, set in old Montreal and its port.

Charla Jones/The Globe and Mail

Montreal was the explicit site of another hymn to transient affection, Suzanne, set in the old city and its port. "The sun pours down like honey on our lady of the harbour," which every Montrealer recognizes as the figure of the Virgin on top of Notre-Dame de Bon Secours, extending her arms to bless all ships and sailors. Suzanne, Cohen told Maclean’s magazine in 2008, "was never about a particular woman. It was more about the beginning of a different life for me … wandering alone in those parts of Montreal." The beneficent Virgin was a personal landmark: "I used to go to that church a lot."

Once Cohen's musical career had begun in earnest, he followed the highway curling up like smoke, mostly to cities in the United States. But in the early 1970s he returned to do what he had till then energetically avoided: to settle and make a family. He rented a place downtown overlooking Parc du Portugal, a postage-stamp green space with none of the expanse or romance of Murray Hill. Here, a block from the city's traditional spine on St Laurent, Cohen and partner Suzanne Elrod welcomed their infant son Adam in 1972, followed by daughter Lorca in 1974.

Cohen bought a house on the same block, which he still owns, and where, as he told an interviewer in 2006, he has done a lot of good writing at the kitchen table. It was here, too, one day in 1975, that an emissary from Bob Dylan's Rolling Thunder tour knocked on the door and asked if Cohen would sing with Dylan that night at the Forum (he declined).

It's a sober two-storey house in grey and sand-coloured brick, with grey windows and doors, and white curtains drawn in every window. No house has ever tried harder not to be noticed, and indeed there's more vivid stuff in the riot of graffiti on two disused buildings across the park.

A young homeless man was bedding down in the park's tiny gazebo the afternoon I visited, and elderly people held down the benches with their debates. From a few steps in either direction, you can see the cross on the top of Mount Royal and the mast of the Olympic Stadium – yesterday's vision of tomorrow, still "somehow unreal."

Much of the rest of Cohen's downtown haunts are gone: Le Bistro, the Parisian-style bar where he met Suzanne Verdal, the nominal inspiration for his song Suzanne; Hotel de France; Dunn's Birdland, and virtually all of the old club district. Ben's De Luxe Delicatessen, a favourite hang-out at Maisonneuve and Metcalfe, was demolished in 2008, and memorialized in a McCord Museum display two years ago.

Back at the Shaar, two large oil portraits commemorate the leadership of Cohen's great-grandfather Lazarus and his grandfather Lyon, both of whom served as presidents of the synagogue. Lazarus, an enterprising immigrant from Lithuania, looks past the painter with rabbinical intensity, his long white beard obscuring the dark mass of his clothing. Lyon's direct gaze is more worldly, and the painter has given due attention to his well-cut three-piece suit. No doubt it came from the family's clothing business, where Leonard briefly and unhappily worked as a young man. His boss was his uncle Horace, whose name is written in a couple of prayer books in the Cohen family pew.

Gideon Zelermyer, cantor of the Shaar Hashomayim congregation, and Cohen collaborator on the artist’s upcoming album, in the Sanctuary of the Shaar in the Westmount neighbourhood.

Sarah Mongeau-Birkett/The Globe and Mail

Cohen riled his uncles with The Favourite Game, which pilloried businessmen who sit in shul with little of the spiritual on their minds. But "there’s a lot of emotion wrapped up in this place for him," says Gideon Zelermyer. "He wanted some kind of authentic Jewish connection."

Shaar music director Roï Azoulay did the choral arrangements for the album, with choir members Jake Smith and Conor O'Neil who also perform in the Montreal band Lakes of Canada. After initial demos of three songs in the Shaar, the choral tracks were recorded at a Montreal studio, to be layered with vocal recordings Cohen made at his home in Los Angeles, with son Adam, producer of the album.

It Seemed the Better Way, one of nine songs on the disc, begins with a choral intro based on an ancient melody associated with the priestly blessing traditionally done by the koheins – every Cohen in the congregation. In the album's title track, Zelermyer improvises on the single word Hineni – "here I am," said by Abraham when the angel of god calls to him to halt the sacrifice of his son Isaac.

"Hallelujah belongs to everyone," Zelermyer says, referring to the refrain of one of Cohen's best-known songs, "but hineni is definitely and emphatically Jewish." The lyrics of the album are filled with references to Jewish liturgy and scripture, but also include Cohen's customary and promiscuous use of Christian imagery.

"He's clearly a spiritual searcher, and he's always been pushing the envelope that way," Zelermyer says. The cantor shows me a self-portrait that Cohen sent him, with Hebrew text and the English inscription: "Just to have been one of them, even on the lowest rung," which Zelermyer relates "to Jacob's ladder, and the angels ascending and descending."

The contrary directions are important, and characteristic: not just up, but down as well, in the continual negotiation between spirit and flesh, elevation and shame, the holy and the carnal. We are still receiving wisdom from Leonard Cohen, a Montrealer whose wanderings in all senses have cycled back to his native city, and whose teachings have so often been concentrated into a three-minute song.